in

Thomas Jefferson's

Civic Architecture

by

Jeff White, '00

|

in Thomas Jefferson's Civic Architecture by Jeff White, '00 |

|

Introduction

Over the course of American History, a few select individuals have been able to capture the essence and meaning of our republic in a way that could be understood by all those living in the United States. One of these individuals was Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, a document that not only captured the goals and dreams of the new republic but also was accessible to all citizens. On July 4, 1776, Thomas Jefferson was able to express the core American political ideals that formed the American Republic, based on "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" and that "all men are created equal." Yet, July 4, 1776, was not the only time that Jefferson attempted to express the core beliefs of America. Over his entire lifetime, Jefferson repeatedly tried to instill these values in the citizens of the United States.

The purpose of this study will to be to analyze how one of these areas, namely Jefferson’s classically inspired civic architecture, instilled values in the citizens of the young republic. We will learn that his choice of the classical architectural motif was not coincidental, since Jefferson and practically all of the founding fathers received an intense classical education. With this in mind, the goal of this project will to be to answer three principle questions:

1. What impact did Jefferson’s classical education have on his political ideology?

2.

To what extent did Jefferson’s political ideology and classical training

impact the

architecture and design of Early American Civic Structures?

3.

How did classical architecture and the design of these buildings symbolize

the

creation of a new American political ideology that was accessible to all?

Part I of the paper will discuss Jefferson’s classical education and training and what role, if any, it had on the formation of his political ideology. Part II will attempt to explain the core beliefs of Jefferson’s political ideology. Part III will analyze the early experiences and travels that shaped Jefferson as an architect, with particular emphasis on those architects that most influenced him. Parts IV through VI will discuss the three major civic structures that Jefferson either played an instrumental role in designing or constructing. These three buildings are:

1.

The Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia (Part IV)

2. The United States Capitol Building (Part V)

3. The President’s House (The White House) (Part VI)

Finally, in Part VII, we will draw conclusions regarding Jefferson’s architecture, with the hope of learning to what extent the architecture contributed to capturing the essence of the American Republic and the formation of a new political ideology, which has now survived for over 250 years.

Part I: Jefferson's Classical Education and Training

Thomas Jefferson’s classical education began rather early in life at the bequest of his father, Peter Jefferson, a surveyor who had little of this type of training. Yet, Peter Jefferson realized the importance of classical education and sent young Jefferson at age 9 to be tutored by Reverend William Douglas, a Scottish clergyman. Under Reverend Douglas’s watchful eye, Jefferson was exposed to Latin, Greek, and French for the first time. In 1758, at age 14, Peter Jefferson died, and this event had a rippling effect on Jefferson’s life for many years to come. According to family lore, the Colonel’s final wish was that his son should continue his classical education.1 Jefferson, later in life, would praise his father for directing his early education, and even wrote to Joseph Priestly on January 27, 1800, that, "I thank on my knees him who directed my early education, for having put into my hands this rich source of delight…"2

Following his father’s wishes, Jefferson went to the Reverend James Maury’s classical academy at age 15. At the academy, Jefferson perfected his Latin and Greek and he was introduced to such classical authors as Cicero, Horace, Livy, Ovid and Homer. This period at Reverend Maury’s academy was a difficult one for Jefferson, as he was trying to adjust to his father’s death and also manage the rather negative relationship that always existed with his mother. As William Randall points out:

Apparently in

his years at Reverend Maury’s school, young Jefferson

could only find

an outlet for his frustrations in copying from the readings

his tutor provided

him as he studied literature. In the pages of his

Commonplace

Book, he protests his mother authority and he broods about

his father’s

death and about death generally…3

What is specifically significant about this aspect of Jefferson, is that at one of the toughest moments of his life, he used the classics for psychological refuge. As we will see, this reliance on the classics would continue throughout his life, whenever he needed to deal with his emotions, tragedies, or at other crucial points during his lifetime.

After completing Reverend Maury’s academy, Jefferson attended the College of William & Mary where he continued his work with the classics and also began his initial training as a lawyer under the tutelage of George Wythe. Jefferson was known as an obsessive student, often studying 15 hours a day. William Sterne Randall notes:

Even before he tackled his

legal studies each morning at eight, he had read

"ethics, religion and natural

law" for three hours "from five to eight,"

including Cicero, Locke’s

essays… After he had survived this

unimaginable seven-hour

morning of philosophy and law…he read more

politics: more Locke, Sidney

and Priestly… The evenings were reserved

for improving "belles letters,

criticism, rhetoric and oratory."4

We once again must recognize that Jefferson’s interest in the classics was not merely an intellectual one, rather the classics served as guide for living his life. Antiquity’s lessons on morality and other such issues were followed by most of the upper echelon of the day. As Louis B. Wright states:

The most significant quality

of Jefferson’s classicism, in its various

manifestations, was its

vitality, the fact that it was a living thing, a part

of everyday life… Jefferson

and the men of learning contemporary with

him still drew on classical

sources for inspiration and instruction. They

still believed that leaders

in a democratic state had an obligation to be

informed- and if possible

be wise.5

Wright’s statement does lead us to another very important point that we must consider--that Jefferson is not the exception to the rule, when it comes to his adherence to his classical education. Rather, almost all the leaders of the founding period were trained in the classics, which allowed for a common language to be established during their interactions. For example, in 1773, in response to the British extension of parliamentary and judicial power within the colonies, a forging group of young leaders were in frequent contact. These individuals included the familiar names of Lee, Mason, Washington, and Jefferson from Virginia and Adams and Warren from Massachusetts. As William Randall notes, "Samuel Adams had urged this network to set up as it top priority the alerting of all colonists to the latest British inroads."6 Beyond this consideration, this network helped facilitate the types of communication that were necessary for such events as the Revolution and the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, and later the Constitution. The common language of the classics is evident in all of these crucial events, and it is important to consider when we are thinking about the reception that Jefferson was anticipating of the classical motif in the design and construction of buildings such as the Capitol and the President’s House. Before we can assess that reception, however, we must determine what Jefferson’s political ideology actually was -- at its most fundamental levels.

Part II : Political Ideology

Over the course of American History, many politicians and citizens alike have attributed many conflicting ideas and political ideologies to Jefferson. Our goal here will be to correctly, as much as possible, identify a more coherent and historically accurate account of what exactly was his political ideology. The most obvious point of departure is to return again to Jefferson’s education as a way of determining the thinkers or philosophies that appealed to him and most directly influenced the formation of his political ideology. From early in his education, Jefferson showed great disfavor for monarchical rule. One of the reasons for this disfavor arose from the classics. Jefferson was extremely influenced by Tacitus, and his historical accounts of Rome’s republican government. Jefferson also read widely about the democracies that existed in Greece and Rome from early in his life and clearly favored many of the aspects of these governments. Yet, it is important to note that Jefferson did not blindly accept these governments as ideal models, rather he showed a "critical eye" towards them. One such criticism of the Romans was their lack of possession of voting records, which did not allow them to accurately track if all citizens had voted or what portion of them had. Jefferson did not develop this criticism on his own, rather he read about it in the works of one of his major influences, the political thinker, Montesquieu. Jefferson copied these sections of Montesquieu verbatim in his Commonplace Book. Jefferson also was influenced by Montesquieu’s writings on the role of the citizens in government. Jefferson copied word for word from Montesquieu that:

A people having sovereign

power should do for itself all it can do well,

and what it cannot do well,

it must do through its ministers. The

people…need to be guided

by a council or a senate. But in order for

people to trust it, they

must elect its members… The people are admirable

for choosing those to whom

they should entrust some part of their

authority.7

While Jefferson adopted some of Montesquieu’s views, such as this one, and his belief in the principle of separation of powers, Jefferson did not adopt other views. As William Randall states, "He passed over, without common-placing a word, Montesquieu’s caveats about the political capacity of the people and his warning that their influence should extend no further than passing laws in the assembly and choosing their natural superiors as their magistrates."8 This "passing over" is just another example of Jefferson’s "critical eye" and his desire to simply use the best parts of a wide range of sources.

If Andrea Palladio was Jefferson’s "architectural bible," then John Locke and his followers were his "political ideological bible." Jefferson spent countless hours studying the philosophy of Locke, especially the sections stating that human beings are meant to be free and equal. William Randall best articulates the importance of Locke to Jefferson when he states:

From Locke, and his Scottish

adherents, Jefferson had adopted the theory

of the Second Treatise of

Government that legitimate authority to govern

was derived from the consent

of the governed, which had first been

granted while mankind had

still been in a "state of nature" when all

human beings were by right,

free and equal. Locke underpinned all of

Jefferson’s political thought.9

With all of these different ideologies in mind, Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Jefferson echoed themes such as that all men have inherent rights and the government exists to secure these rights, while pointing out that government derives it authority from the people. Yet, this was not the first time that Jefferson would make such statements. Two years earlier, in 1774, Jefferson wrote in "A Summary View of the Rights of British America," that, "kings are the servants, not the proprietors of the people."10 This statement again points out that Jefferson’s political ideology was in fact formed before the actual writing of the Declaration of Independence, discounting some scholar’s arguments that Jefferson was simply given the job because of his writing skills.

Jefferson continued to develop his ideology in the newly formed Virginia Legislature that was established after the colonies declared their independence. Jefferson argued for the adoption of some of his "cornerstone" principles, which included the end of primogeniture, free public education, liberalizing the penal code, and ensuring religious freedom. The freedom of religion has been a central facet to our constitutional system and has even been protected by the Supreme Court. Jefferson had a direct interest in protecting this liberty, as he was considered by many, to be at best, one of little religious faith, and at worst, an atheist. Jefferson stated in his Notes on Virginia, that the Anglican Clergy in Virginia had "showed equal intolerance in this country with their Presbyterian brethren, who had emigrated to the northern government [Massachusetts]."11 Jefferson identified the same sorts of injustices that had been occurring in England by the Anglican Clergy because he firmly believed that this type of discrimination had to be purged from the American Republic.

Another interesting aspect of Jefferson’s political ideas is his abolishment of primogeniture, a system that greatly benefited Jefferson. But rather than establishing an aristocracy based on birth, Jefferson advocated a system based on "virtue and talent." Once again, Jefferson emphasized the freedom of the individual by allowing those with virtue and talent to move up the social ladder to leadership, no matter their birthright. Joseph Ellis points out that Jefferson was:

Alone among the influential

political thinkers of the revolutionary

generation, Jefferson began

with the assumption of individual sovereignty,

then attempted to develop

prescriptions for government that at best

protected individual rights

and at worst minimized the impact of

government or the power

of the state on individual lives.12

With this individualism in mind, Jefferson attempted to implement a "pure republican" government when he became President in 1801. His goals included reducing the size of government and rolling back many of the reforms that the Federalists, led by his archrival Alexander Hamilton attempted to implement. In Jefferson’s ideal government, there would be no need for an energetic, assertive government, rather a great deal of political autonomy would be granted to citizens. But beyond the voluntary consent of the individual and a small government, it has been difficult for many scholars to grasp what Jefferson meant when he used the term, "republican." Joseph Ellis suggests that:

Indeed one of the most alluring

features of Jefferson’s formulation was its

eloquent silence on the

whole question of what a republican government actually

entailed. Perhaps the most

beguiling facet of Jefferson’s habit of mind was its

implicit assumption that

one need not worry or even talk about such complex

questions, that the destruction

of monarchy and feudal trappings led naturally to

a new political order.13

Yet, it seems likely that by defining a "republican" government specifically,

Jefferson

would not be allowing for interpretation by others. The U.S. Constitution

is similar in laying down core principals, but also allowing for a great

deal of discussion and interpretation among decision makers.

Before we can make solid conclusions about the political ideology of Thomas Jefferson, we must deal with two issues that are often raised in objection to his form of government. First, it often was argued that Jefferson was completely dedicated to the rights of the states, and that they superceded the rights of the federal government. While Jefferson was an advocate for a weaker federal government, this did not suggest that he did not value unity within the entire nation. One example of his belief in unity occurred in 1774, when the British established an embargo in Boston. Jefferson drafted a resolution in protest, which stated that the colonies must with "one heart and one mind firmly oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American rights."14 Even before the nation was formed, Jefferson advocated "American" rights, not just the rights of Virginians. Throughout his political career, Jefferson simply attempted to make sure that the federal government did not abuse its power and that the states and individuals would also maintain their sovereignty. This does not mean, however, that Jefferson was opposed to a national unity and self-concept.

Another important consideration about Jefferson’s political ideology is that it did not paralyze him from making decisions that would benefit the country. An obvious example of this is the Louisiana Purchase, a land deal that required Jefferson to make a quick, presidential decision that went against many of his beliefs regarding the dangers of a powerful executive. Yet, even though this was a dilemma for Jefferson, his great vision for the future allowed him to move forward with the deal. Jefferson wrote Adams in 1816, that "I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past."15 Jefferson’s vision is a crucial element to not only his political ideology, but also his architecture, as it advocates a more perfect future.

In the end, the political ideology of Jefferson, is in fact, a set of principles that are focused on the liberty of the individual, but is maintained by the order of the government. Perhaps the most important facet of his political ideology was that he was able to express it to a wide range of people. The Declaration of Independence, argumentation of which was based upon formal classical rhetoric, was one of the first attempts to "express the American mind." As William Randall states, "The genius of Jefferson’s writing lay in his ability to take deep and complicated concepts of history, law, and philosophy and clothe them in easy, grateful, direct, almost simple language."16 The ability to simplify the essence of the American Republic did not end with his writing, rather it extended to other areas, such as that of his civic architecture.

Part IV: The Shaping of an Architect

Jefferson’s ability as an architect is often overlooked because of his instrumental role as a statesman during and following the American Revolution. But Jefferson took his role as an architect very seriously, as he states in a letter written to James Madison in 1785: "…It is an enthusiasm of which I am not ashamed, as its object is to improve the taste of my countrymen, to increase their reputation, to reconcile them to the respect of the world and procure them its praise."17 Jefferson’s goal in introducing classically inspired architecture to his countrymen was indeed to improve their taste, and also to move away from the English architecture that was previously dominant in the colonies. Jefferson wrote in 1786 during a trip to England that, "Their [English] architecture is in the most wretched style I ever saw, not meaning to exact America, where it is bad, nor even Virginia, where it is worse than in any other part of America, that I have seen."18 Throughout his life, Jefferson would strive to improve the quality of architecture in America, at least as he perceived excellence in architecture.

The most appropriate place to begin a discussion of Jefferson’s architecture is Williamsburg, where Jefferson lived during his years at the College of William & Mary beginning in 1760. In Williamsburg, Jefferson would be introduced to his architectural mentor, Richard Taliaferro, who was George Wythe’s father-in-law. Jefferson lived in his home for much of his time in Williamsburg (Figure 1). Not a great deal is known about Taliaferro, except that the acting governor of Virginia acknowledged that he was the "leading architect of the colony."19 The major contribution that Taliaferro made to Jefferson’s training as an architect, was access to his library, where a young Jefferson was most likely exposed, for the first time, to Andrea Palladio, an Italian architect, who shaped Jefferson’s architectural understanding to the greatest extent. While the respected Jefferson biographers Dumas Malone and Fiske Kimball have concluded that Jefferson was at least exposed to an English translation of Palladio, the jury is still out whether he knew Palladio in the original form at this early date. The first mention that Jefferson makes of Palladio is in 1769, when he catalogued his books before he went to Paris. Fiske Kimball notes that the first two entries are Palladio, and through further investigation, Kimball was able to date these acquisitions to the year c.1769. Simply stated, Jefferson knew Palladio before he went to Paris, and already had begun to experiment with the Italian architect’s designs and theories.

The appeal of Palladio was made clear to all those surrounding Jefferson as he often stated that, "Palladio is the bible and stick close to it."20 Clay Lancaster remarks on Jefferson’s fondness for Palladio that:

The relationship established

by the Italian architect between architecture

and natural law appealed

to the American, and the codification of

proportions was accepted

as most authoritative; and if the first made its

appeal to sentiment, the

second was based upon intellectual and

archaeological grounds.

Spiritually, therefore, Jefferson was the

descendant and willing follower

of Palladio.21

Even though Jefferson began by simply being a willing follower of Palladio, that dependence would all change during his years in Paris as an ambassador. Eventually, Jefferson would evolve as an independent and self-confident architect and no longer simply copy the works of Palladio. As Louis B. Wright so eloquently sums up:

In architecture, as in history

and literature, he took from the classics

everything that was useful

and adapted it to his own ends without

becoming a slave to convention.

Such skill of adaptation and creation

could not have been shown

by even an inspired dilettante; it was proof of

painstaking and studious

application to his art, and art which the best critic

of Jefferson’s architectural

ability [Fiske Kimball] describes as the "fusion

of retrospection and of

science," and "above all, a critical historic spirit."22

Wright alludes to the central theme that ran through Jefferson’s entire life - that is, critically analyzing information in order to identify the most useful elements of it to help form a more ideal and perfect theory.

Jefferson’s evolution as an architect progressed to a new level during his years in Paris, from 1784-1789. While Jefferson despised almost everything that was English, he fell in love with the French architecture and their other artistic endeavors and achievements. However, as Dixon Wecter states:

Abroad, Jefferson grew more

aggressively American, seeing England as

an aristocracy besotted

with liquor and horseracing, and France as a land

where marital fidelity is

"an gentlemanly practice." He also loved to

magnify the virtues of his

native land, solemnly assuring Crevecoeur that

New Jersey farmers probably

learned how to make "the circumference of

a wheel of one single piece"

from Greek epic poetry, "because ours are the

only farmers who can read

Homer."23

Even though Jefferson did not totally agree with all aspects of Parisian

culture, he still was enamored by its architecture. One such structure

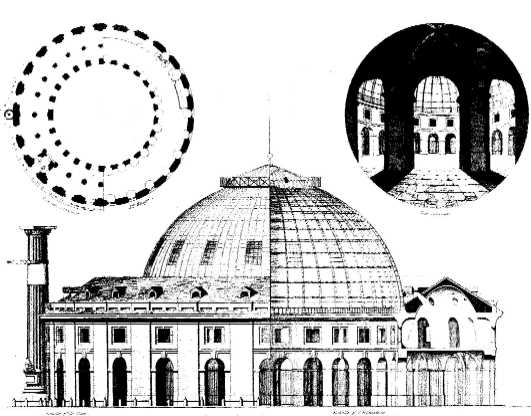

was the Halle aux Bles (Figure 2), a building

with a freestanding dome that consisted of glass panels for the light to

shine through. Jefferson many years later would attempt to install this

type of dome within the U.S. Capitol building. The other pivotal structure

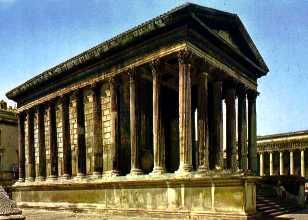

in France that greatly influenced Jefferson was the Maison Carree

(Figure 3) in Nismes, France. This structure

would serve as the model for the first major classically inspired civic

structure to be built in America. Jefferson, with the permission of the

Virginia State Assembly, had chosen the Maison Carree as the model for

the Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia.

Part IV: The Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia

Thomas Jefferson understood the importance of the role and responsibilities that had been placed in him by the Virginia Assembly. It was not simply to commission an architect or select a model for the capitol, but rather it meant so much more. It was an extraordinary chance for America to break its cultural and political ties with England and establish its own identity and cultural legitimacy. In order to help establish this legitimacy, Jefferson chose a model with a classical motif because he believed that classical architecture would most facilitate this goal. Jefferson explained this choice in a letter to James Madison on September 20, 1785:

We took for our model what

is called the Maison Quarree of Nismes, one

of the most beautiful, if

not the most beautiful and precious morsel of

architecture left us by

antiquity… It is very simple, but it is noble beyond

expression, and would have

done honor to any country, as presenting to

travelers a specimen of

taste in our infancy, promising much too for our

maturer age.24

This goal of national legitimacy would be the central theme in all of Jefferson’s civic architecture.

Jefferson choose the Maison Carree for the model of the state capitol before he even saw it in person because he was so awe-struck by its beauty from drawings. The Maison Carree was beautiful to Jefferson because it was an excellent example of the type of classical architecture that he admired and embraced throughout his life. Jefferson did not visit the Maison Carree until after the design for the Richmond Capitol was completed, and his admiration for the structure only increased once he viewed the building. In a letter to Madame de Tesse, Jefferson wrote a passionate description of the building. This is significant because he kept these passions and desires private during most of his life. He wrote in 1787, "Here I am, Madame, gazing whole hours at the Maison Carree like a lover at his mistress. Here, Roman taste, genius and magnificence excite ideas analogous to yours at every step."25 While Jefferson’s love and passion for the Maison Carree are not in question, scholars have debated the extent to which Jefferson was involved in the actual design and construction of the model that was to be used for the Capitol in Richmond. The controversy stems from the involvement of another architect, M. Clerisseau. Jefferson was searching for an "architect whose taste had been formed on a study of the antient models…"26 The result of this search was the hiring of the French architect, M. Clerisseau, about whom Jefferson wrote in his memoirs in 1821:

I was written to in 1785

(being then in Paris) by directors appointed to

superintend the building

of a Capitol at Richmond, to advise them as to

a plan, and to add to it

one Prison. Thinking it a favorable opportunity

of introducing into the

State an example of architecture in the classic style

of antiquity, and the Maison

quarree of Nismes, an ancient Roman temple,

being considered as the

most perfect model existing of what may be called

cubic architecture, I applied

to M. Clerissualt, who had published drawings

of the Antiquities of Nismes,

to have me a model of the building made in

stucco, only changing the

order from Corinthian to Ionic, an account of the

difficulty of the Corinthian

capitals. I yielded, with reluctance, to the taste

of Clerissualt, in his preference

of the modern capitals of scamozzi to more

noble capital of antiquity.27

This excerpt may best illustrate the crux of the debate that exists between scholars. One set of scholars argues that Clerisseau was the principle designer of the Capitol Building. The other set is quick to point out that this occurrence of Jefferson conceding to Clerisseau is the exception and not the rule, and on the whole, the French architect was hired for his technical skill as a draftsman to elaborate on Jefferson’s original plans. Fiske Kimball, one of most respected Jeffersonian scholars, has published the most conclusive work on this question to date. Kimball studied many of the original Capitol drawings and attributed them to Jefferson through a variety of techniques. As Kimball states:

Their identity of technique

with other drawings of Jefferson’s, however, is

equally striking. Self taught

as a draughtsman, and approaching architecture

with geometric and formal

preconceptions fostered by his allegiance to

Palladio, Jefferson’s manner

was calculated, mechanical, and precise

– the very antithesis to

the free and intuitive method of men of artistic training,

like Clerisseau.28

The basis for many of these sketches was Palladio’s, Book IV, giving further credence to the fact that Jefferson did indeed draw and design the sketches for the Virginia Capitol. Architectural historian, Jack McLaughlin offers additional support for Kimball, as he points out that Jefferson’s drawings could be identified because of their uniqueness in attention to exact details. McLaughlin explains that:

His [Jefferson’s] architectural

drawings are symbolic of his kind of

compulsive personality.Not

only did he feel the need to save and account

for everything – money,

books, records, facts, but his careful, slavishly

perfect drawings were an

absurdity in the building trades where carpenters

and bricklayers are often

lucky if they can keep to the inch rather than the

ten-thousandth of an inch.29

Yet, even though the evidence apparently proves that Jefferson had drawn these designs, Kimball also points out that Jefferson expressed his ideas for the building immediately after the commission granted their approval and before he was able to find "an architect whose taste had been formed on a study of the antient models."30

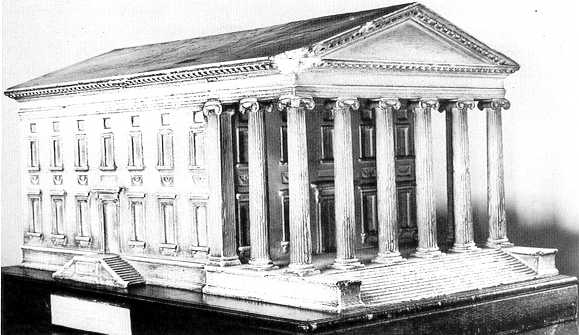

Beyond these considerations, the model (Figure 4) that was based on the design (Figure 5) which was given to the commissioners almost entirely conformed to the ideas and developments of Jefferson, not Clerisseau. As Kimball points out, "The use of the Ionic order, the number of bays on front and side, the main proportions, the principal divisions of the interior and many details agreed with the model and with Jefferson’s intentions."31 In the end, the most convincing evidence in favor of Jefferson’s authorship of the final design deals with the dimensions of the model, which "are in general, with great exactness, twice the corresponding dimensions of Jefferson’s final studies."32 In addition the sketch that was given to the Directors proposed a total length of 153 feet, 6 inches, which is identical to the length in the Jefferson study.

In addition to these differences, there are other aspects that we must consider. First, the final design used "modular" forms of measurement, a practice directly derived from Palladio’s inspiration, Vitruvius. However, even though Jefferson often used these units, Clerisseau used French feet as his units of measurement in the plates that he constructed for the Maison Carree. Also, in Clerisseau’s plate, the intercolumniation, or spacing between the columns, averaged about one and three-fourths modules, instead of the traditional classical spacing of one and half modules, as was repeated in the Richmond Capitol.

Kimball also points out that features such as the doors, windows, cornice and capitals are all derived from Palladio and that Jefferson had already used similar features in his designs for early Monticello. Kimball states:

As in Jefferson’s earlier

work, the classical forms are still rationalized

according to Palladian rules:

the height of the pediment, for instance, is

determined by Palladio’s

general formula, two-ninths of the span, instead

of the proportions given

for the Maison Carree.33

Jefferson’s attention to detail and his close adherence to many of the Palladian principles caused tension between the two architects. Jefferson often overruled many of Clerisseau’s decisions in this regard. Their relationship is important to discuss because many scholars assert that Clerisseau considered Jefferson a mere "amateur," which must have had an impact on the authoritarian concentration in their relationship. Yet, the word "amateur" in the 1780’s did not necessarily have the same meaning as it does in present day America. Even though Jefferson was not a "professional" architect, he had an extensive background in architecture to which Clerisseau obviously was exposed. Also, Clerisseau did not alter much of Jefferson’s design - further proof of his secondary role in this project. One of the reasons why few alterations were made was because Jefferson strictly adhered to his design. Jefferson succumbed only a few times, such as when Clerisseau suggested that the bays of the front portico be two instead of three deep for lighting purposes. One final piece of evidence that leads to the conclusion that Clerisseau played a secondary role in the Capitol design is derived from the expense report that was issued from Clerisseau’s firm. Clerisseau did not charge his regular rate for his full professional architectural services. Rather, as Fiske Kimball states:

Clerisseau’s letter of acknowledgement

bearing the same date, likewise

speaks only of payment of

expenses and makes it certain that he regarded

the transaction as Jefferson

did, rather as a loan of his draught men for the

drawing up of Jefferson’s

design, than as regular professional services.34

The evidence seems to point to two answers to why Jefferson hired Clerisseau. First, Jefferson needed Clerisseau’s drafting skills to fully elaborate his design. Second, Jefferson may have needed to reassure the directors in Virginia that a professional architect was involved with the project. Yet, in reality, Jefferson took the lead and became the architect that he himself had been sent to search for.

The significance of the Capitol Building in Richmond exists on many different levels. First, the event of its design and construction marked an important evolution in regards to Jefferson, the architect. Before this design, Jefferson had simply copied much of Palladio and strictly adhered to all of his principles. In this case, he not only doubled the size of the Maison Carree, but Jefferson introduced the Roman temple form to Virginia, and to the new nation. As Paul Norton states, "This period marks Jefferson’s change from a copier of the Renaissance Master Palladio, whom he now saw as only a secondary source for knowledge of the classic style."35 In this case, Jefferson simply adapted Palladio’s architecture to meet the needs of the new republican government. He did this in a visual sense, as "the temple form, with its unrivaled abstract unity blinding observers to faults of relation…"36 Secondly, and more importantly, the Capitol Building served a psychological purpose. As Jefferson stated, "The Virginia capitol was ‘the first building destined specifically for a modern republican government, and the first to give such a government a monumental setting."37 Jefferson was creating a new government, so he therefore needed a new type of structure and architecture. Simply replicating the Maison Carree would not have had the same effect, even though it is of classical origin. The effect of such a replication would be different because it is a French building and will always be identified as such. But when Jefferson changed its dimensions, its order, and modified the Roman temple front, the structure went through a rebirth. It was now an American building, with an American identity and political ideology. As Fiske Kimball states:

The use of the simple and

crystalline temple form, the colossal order, the

monumental disposition of

the interior – the chief remains of his ideas- are

what gives the model its

novel dignity, its expressiveness of the majesty

of the new and sovereign

republican state.38

The portico has been referred to as the "front piece to all Virginia"

but in a much larger sense, the Capitol Building in Richmond may have been

the first frontispiece for the entire republic, signifying a new set of

beliefs and goals. Jefferson again played an instrumental role in this

process and he would continue to serve in this role as the country prepared

for one its earliest challenges; establishing a national capitol.

Part V: The United States Capitol Building

In the early 1790’s, the founding fathers began to plan for the construction of the National Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. Their original intent was to build a city in a location that would forge unity for the 13 states. Thomas Jefferson obviously played a large role in achieving this goal, as he had done in the building of the Capitol in Richmond. Paul Norton states, "He [Jefferson] recognized the Capitol as a symbol of national solidarity. Its architectural magnificence could convincingly establish in the minds of foreigners voyaging to our shares the strength of our union."39 As a result of the attempt to establish this visual effect, the Capitol was built high above the city on a large hill, which, as Norton points out, "The Roman Capitol, standing high above the city at one end of the Via Sacra, was certainly the ideological source for the American Capitol which crowned the highest hill in the eastern quarter of the city…"40 Once again, the early leaders of the Republic returned to Classical Antiquity for inspiration and guidance.

In March of 1792, Jefferson, who was secretary of state, announced that the Capitol design would be decided by a contest (Figure 6) with the winner receiving five hundred dollars. There were no provisions in the guidelines regarding taste, other architectural features, or purpose, only a practical description of the type of building needed. Yet, we must analyze why virtually all of the designs that were seriously considered by Jefferson and the committee were classically inspired works. The answer can be traced back to 1791, when Jefferson wrote to Charles L’Enfant explaining his ideas for the design of the capitol. Jefferson wrote, "Whenever it is proposed to prepare plans for the Capitol, I should prefer the adoption of some one of the models of antiquity which have had the approbation of thousands of years…"41 Jefferson made it known that he believed that the only proper design for the Capitol would be classically inspired and he dismissed the designs that relied on English or Renaissance influences. In the end, there were three designs that relied on classical architecture, two of them directly influenced by Jefferson himself. First, and most obvious was Jefferson’s submission (Figure 7), which was submitted anonymously, modeled after the Roman Pantheon (Figure 8). The other design that Jefferson influenced was that of Stephen Hallet (Figure 9), who finished second in the competition and later would be named the lead architect on the project. Hallet showed his design to Jefferson in 1791 (Figure 10), at which point Jefferson suggested changing the design to a "temple" form with a free-standing portico. Fiske Kimball supports this assumption when he states, "Letters preserved at the Department of State make it clear that the suggestion of a temple form came to Hallet from Jefferson, to whom he had previously shown a design of a different character."42 Hallet’s design was not chosen because of George Washington’s concern that the "Distribution of Parts is not sufficiently convenient."43 Washington’s desires for "grandeur, simplicity, and beauty of the exterior" were met in the late entry of Dr. William Thornton, whose design (Figure 11) was eventually approved by the committee in April of 1793. Jefferson agreed with this decision, as he wrote that "Dr. Thornton’s plan has… so captivated the eyes and judgment of all as to leave no doubt you will prefer it when it shall be exhibited to you…"44 The cornerstone for the Capitol was laid in 1793, and architects such as Stephen Hallet, George Hadfield and James Hoban supervised construction until the end of the 18th Century. Beginning in 1803, a new professional architect, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, would be appointed, who would take charge of the construction of the Capitol, or so he thought.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe was one of the first professional architects to practice in America. He was born in England in 1746 and attended the Fulneck School from ages four to twelve, where he received a classical education, consisting of Latin and Greek, and he also was exposed to introductory geometry and algebra. He went on to receive his training as an architect under the guidance of S.P. Cockerell, who was an accomplished English architect. Latrobe’s architecture was grounded in simplicity, geometric power, and rationalism. Latrobe explained his architectural influences when he wrote:

My principles of good taste

are rigid in Grecian architecture. I am a bigoted

Greek in the condemnation

of Roman architecture of Baalbec, Palmyra, and

Spalatro… Whenever, therefore

the Grecian style can be copied without

impropriety, I love to be

a mere, I would say a slavish copyist.45

Even though Latrobe’s architecture was rooted in the classical tradition, he emphasized that it had to be functional and able to be used in the current time period. Along with his focus on creating functional architecture, Latrobe wanted to achieve another goal. As he wrote in his journal on October 28, 1806, Latrobe believed that, "With public exhibitions of art I shall take still greater liberties, and I am so fortunate to provoke a defence, I shall attain my object, for the public will listen and learn."46 At the outset, it is important to note that Latrobe seemed to have the same goals as Jefferson in forming a political and cultural ideology that would be expressed through these public architectureal structures to the general citizenry. The mutual commitment to symbolic architecture that Jefferson and Latrobe shared would not change and would lead to a life-long loyalty and friendship between the two. While they both agreed that the classical architecture should be used in expressing the message, they differed in what classical architectural source they would draw from – a difference which would cause much debate between the two during the construction of the capitol. Jefferson strictly adhered to Roman influences as presented by Palladio while Latrobe was an advocate of Greek architectural influences. Latrobe explained the difference between the styles in a letter in 1804, when he wrote that:

Palladio & his successors

& contemporaries endeavored to establish fixed

rules for the most minute

parts of the orders. The Greeks knew of no such

rules, but having established

general proportions & laws of form &

arrangement, all matters

of details were left to the talent of individual

architects.47

Obviously, Jefferson did not agree with this approach and many mini debates would occur because of these differences.

Even though Jefferson and Latrobe disagreed with each other’s philosophy of architecture, they agreed on one introductory point; that is that Thornton’s design and the initial execution of the Capitol was poor and had to be changed. Latrobe reported to Congress in 1804, that Thornton’s design was a "picture and not a plan," which prompted his efforts to propose some of his original ideas for the Capitol. One of these changes was to eliminate the use of ellipses within in the building, a major part of Thornton’s plan. Latrobe argued that the Romans and Greeks never used these shapes because they were not pleasing to the human eye. While Latrobe was conceiving a new plan, Jefferson was intensively involved in the actual construction of the Capitol, which at many times aggravated Latrobe. As Paul Norton explains:

While Latrobe was contriving

plans in Philadelphia, Jefferson was acting

as an overseer for the Capitol,

though without Latrobe’s consent. So

essential to the well-being

of the city and the nation did Jefferson consider

the Capitol that he spent

many hours examining the plans and inspecting the

actual progress of work,

hoping that by his doing so the building might be

completed sooner.48

One of most important questions that we must answer in light of these considerations is what exactly was the relationship that existed between the two. Was it one in which Latrobe, the professional, was in charge of the construction, and Jefferson was simply a "presidential" pest? Or was it something deeper than that, a mutual respect that existed, that allowed for each man to make a substantial contribution to a shared goal? The answers to these questions may in fact be hidden in a series of events that occurred during the construction of the Capitol, which we will refer to as the "lanthern controversy."

The subject of the "lanthern controversy" involved the covering or ceiling of the newly constructed House of Representatives Chamber. Jefferson wanted the ceiling to resemble the Halle aux Bles (Figure 2), in that it would have circular ribs with skylights in between the ribs to allow the sunlight to illuminate the chamber. However, Latrobe was opposed to this idea because of the likely danger of a leakage from these joints. As Virginia Daiker states, "The degree and quality of light and its appropriateness for the legislative chamber, heat and moisture condensation inside, accumulation of dirt and snow on the sky lights, and breakage and consequent leaks constituted major problems with Jefferson’s proposed ceiling."49 In response to these concerns, Latrobe proposed a "lanthern" or cupola with vertical frames of glass that would be more practical and with less risk of leakage. Jefferson eventually yielded in a letter on September 8, 1805, in which he wrote:

I cannot express to you the

regret I feel on the subject of renouncing the

Halle au bled lights of

the Capitol dome. That single circumstance was

to constitute the distinguishing

merit of the room, and would solely have

made it the handsomest room

in the world, without a single exception.

Take that away, it becomes

a common thing exceeded by many.50

Jefferson also decided that he would allow Latrobe to make the determination whether to proceed or not with the skylights at all. This put Latrobe in a very difficult position in which he described in a letter to John Lenthall five days later that:

The President very reluctantly

gives up the skylights to my decision,

which is placing me in a

most unpleasant situation. I shall therefore let

them lie over till it is

absolutely necessary to decide and even then my

conscience and my common

sense I fear will reject them in spite of my

desire to do as he wishes.51

This letter exposes many facets of the Latrobe/Jefferson relationship. Even though Jefferson has given the decision-making power to Latrobe, Latrobe struggles with it because of his desire to satisfy Jefferson. Latrobe could have simply made the decision based on his professional judgment without these other considerations but he does not, thus showing his mutual respect for the architecturl talents of Jefferson. A month later, on October 23rd, Latrobe again exhibits this mutual respect. He wrote, "I am very unfortunate to be obliged to oppose a man I most respect, and ought to obey, in so many points. I have, however, a queer scheme of lighting the House of Representatives which will please him."52 This "scheme" (Figures 12A & 12B) was the substitution of five rectangular panel lights that would be placed in between the ribs. Jefferson was pleased with this plan as he wrote, "it would be beautiful… and a more mild mode of lighting, because it would be original and unique."53 There are two important points that should be understood from this series of events. First, Latrobe compromised, even though he did not have to, because he understood the importance of the type of ceiling that Jefferson so avidly wanted. Secondly, as will be seen later, Latrobe understood the importance of the Jeffersonian scheme because he recognized the overall goal that Jefferson was trying to achieve. Latrobe had previously written to John Lenthall, "I will give up my office sooner than build a temple of disgrace to myself and Mr. Jefferson."54 The Capitol could not be just an ordinary building, rather it had to a new, creative, awe-inspiring structure that would represent the ideals of the new republic.

Even with this agreement, the "lanthern controversy" continued to flare up over the next year. Latrobe had placed a "temporary" lantern in the chamber for illumination purposes and this concerned Jefferson. In a letter to Lenthall on October 21, 1806, Jefferson wrote, "The skylights in the dome of the Representatives Chamber were a part of the plan as settled and communicated to Mr. Latrobe. That the preparation for them has not been made, and the building now to be stopped for them, has been wrong."55 The issue of the lantern illustrates a debate in which Latrobe and Jefferson often engaged. Latrobe did want to adhere to classical architecture, as did Jefferson, but he also realized that certain aspects had to be changed if the building was to be functional in its contemporary time period. At these times, Latrobe would veer from the classical architectural course and move to this type of functionality scheme. Jefferson at times showed his displeasure for this movement, as, for example, he did in a letter written on April 22, 1807:

It is with real pain I oppose

myself to your passion for the lanthern

(or cupola), and that in

a matter of taste, I differ from a professor in his

art. but the object of the

artist is lost if he fails to please the general eye.

You know my reverence for

the Graecian & Roman style of architecture.

I do not recollect ever

to have seen in their buildings a single instance of a

lanthern, Cupola, or belfry…

on the whole I cannot be afraid of having our

dome like that of the Pantheon,

on which had a lanthern been placed it

would never have obtained

that degree of admiration in which it is now

held by the world.56

Jefferson again showed his concern for how citizens and the world would look upon this new symbol of American strength and liberty. Latrobe responded with a letter on May 21st in which he restated his position on the subject:

In respect to the general

subject of cupolas, I do not think that they are

always, nor even

often

ornamental. My principles of good taste are rigid

in Grecian architecture…

Yet I cannot admit that because the Greeks and

Romans did not place elevated

cupolas upon their temples, they may not

when necessary be regarded

also beautiful… It is not the ornament, it is

the

use I want.57

Latrobe understood the importance of beauty, yet he still realized that in this instance, for the goal of functionality, he would have to move away from the classical architectural motif. He was simply adapting the architecture to his needs, as Jefferson did with the Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia. The "lanthern controversy" exposed many things about both men. First, they obviously had instances where they had serious differences of opinions about the design of the Capitol, such as in this case. Yet, even though these disagreements occurred, Latrobe still recognized the importance of what Jefferson advocated and the end that he was trying to achieve, but at times Latrobe disagreed with the means to that end. The most poignant and striking letter that was written between the two, which illustrated Latrobe’s understanding of the goal Jefferson was trying to achieve, was written on August 13, 1807, when Latrobe had discovered that the new ceiling had suffered some damage from leakage. In a passionate letter to Jefferson, Latrobe wrote:

It is not flattery to say

that you have planted the arts in your country. The

works already in this city

are the monuments of your judgment and of your

zeal and of your taste.

The first sculpture that adorns an American public

building perpetuates your

love and your protection of fine arts. As for

myself, I am not ashamed

to say that my pride is not a little flattered and

my professional ambition

roused when I think that my grandchildren may

at some future day read

that after the turbulence of revolution and of faction

which characterized the

two first presidencies, their ancestor was the

instrument in your hands

to decorate the tranquility, the prosperity, and the

happiness of your government.58

In this moment of vulnerability, Latrobe opened himself up to Jefferson, and allowed a glimpse into his heart. Latrobe exhibited his understanding that he was not simply building a structure, but that he was part of something greater, the building of an identity of a republic. Latrobe understood this goal when he had the Italian sculptor Frazoni, redesign the immense eagle that was to be placed in the Capitol. Latrobe stated that the original design was "an Italian, or a Roman, or a Greek eagle, and I want an American eagle."(Figure 13)59 He again showed an awareness of Jefferson’s goal of establishing an American cultural and political ideology, even after Jefferson was no longer President, when he invented a capital that used the tobacco plant as its model (Figure 14). Paul Norton suggests that, "The use of a modern and American plant for a capital, instead of the acanthus or other foreign species, marks him as leading us inevitably towards a conscious nationalism."60 Latrobe sent one of these capitals to Monticello as a gift for Jefferson. In addition, when Latrobe was commissioned to reconstruct the Capitol after the British burned it, he always kept Jefferson informed on the changes that were made and included detailed descriptions explaining why they were made. Jefferson responded in kind, and reiterated to Latrobe on July 12, 1812:

I shall live in the hope

that the day will come when an opportunity will be

given you of finishing the

middle building in a style worthy of the two

wings, and worthy of the

first temple dedicated to the sovereignty of the

people, embellishing with

Athenian taste the course of a nation looking

far beyond the range of

Athenian destinies.61

Even though Latrobe did not finish the complete building, his successors

did have a keen understanding of Jefferson and his goals. Robert Mills,

William Strickland, and

Charles Bulfinch, who were

Latrobe’s immediate successors, all had an architectural connection to

either Jefferson or Latrobe. Jefferson had introduced Bulfinch to Paris

in 1786, and Mills stayed at Monticello for a time.62

These connections illustrate that even after Jefferson had died, his architectural

influence lived on through other architects and the Capitol was completed

and continued to be restored with an eye towards its inspiration from classical

antiquity. In the end, George Hazelton may sum up most completely the importance

and significance of the Capitol:

The eyes of the world are

upon the great Capitol: the poor look to it as the

bulwark of liberty and prosperity,

the rich for protection of invested rights;

the savage for learning

and assistance; the jurist for law; the politician as

the goal of his ambition…

It is the abode of the Goddess of freedom in the

New World.63

The Capitol may mean different things for different people, but it, in a word, means what Jefferson envisioned it to mean; "America." The building itself – is a living expression of the essential mathematical principles of classical architecture – namely, symmetry and proportion; yet the logic of that architectural tradition does not stifle, the personality of the building which intermingles vast space and freedom – a perfect description of the republic. Yet, Jefferson influenced not only the Capitol Building while he was in Washington, D.C. For, if the Capitol was his full-time architectural job, then the construction and renovation of the President’s House could be considered his second job.

VI: The President’s House

While the Capitol was the most important building to Jefferson since it represented the voice of the people, the President’s House was treated in a different manner by Jefferson, who had always deplored the English monarchy and tried to make sure that this type of executive would not exist in the new American Republic. The executive was to be the servant of the people and the new President’s House was to represent this new political concept. In order to achieve this goal, Jefferson also advocated a physical structure that was classically inspired in an attempt to provide a national symbol for the fall of the English monarchy and rise of the newly formed American Republic.

Jefferson and the founding fathers also chose the strategic location of the President’s house, as they wished to link visually all the principal public buildings of the new capitol. Jefferson, who was intimately involved in the planning of all aspects of Washington, D.C., stated in a memorandum prepared on November 29, 1790, "For the President’s house, …2 squares should be consolidated, for the Capitol & offices one square. for the Market one square. for the Public walks 9. squares consolidated."64 In this memorandum, Jefferson made the first reference to the Mall (Figure 15) and that Washington, D.C., was to consist of right angles, which would form squares. Another important point is that the Capitol Building was the one set atop the hill, not the President’s House, which again points to the Jefferson’s belief in the importance of the people and their voice, as represented through the Congress.

As with the Capitol Building, Jefferson was instrumental in the competition that was used to choose the design for the President’s House. The advertisement that was issued in newspapers stated:

A premium of 500 dollars

or a medal of that value at the option of the party

will be given by the commissioners

of the federal buildings to the person

who before the fifteenth

day of July next shall produce to them the most

approved plan, if adopted

by them for a president’s house to be erected in

the city… It will be a recommendation

of any plan if the Central part of it

may be detached and erected

for the present with the appearance of a

complete whole and be capable

of admitting the additional parts in future,

if they shall be wanting.65

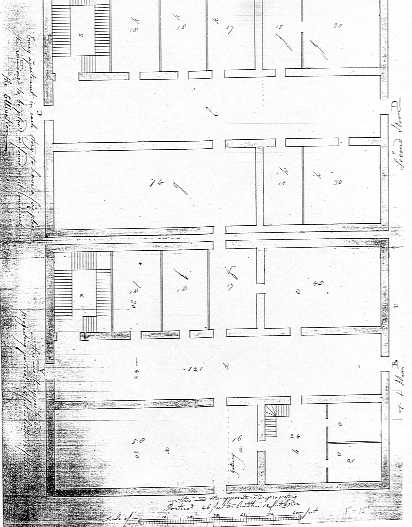

The advertisement urged architects to design a building that could be easily extended in the future when the country would be in a better financial situation. As will be seen later, George Washington and the other commissioners used a criterion in choosing the winner of the competition, which was consistent with the advertisement The competition was officially closed on July 15, 1792. Of the architects that submitted designs, the two that are the most important, were the winning design of James Hoban and a design submitted anonymously by Thomas Jefferson himself.

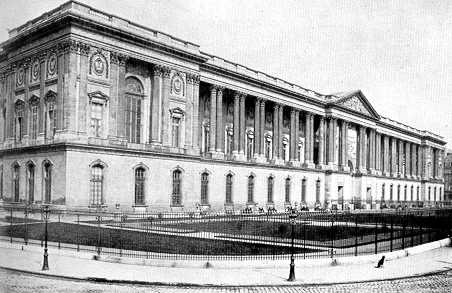

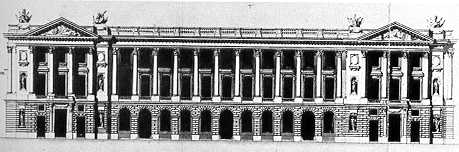

Jefferson, as we have come to expect, believed that the President’s House should be rooted in the architecture of classical antiquity. In his famous letter to L’Enfant on April 10, 1791, he states, "…For the President’s house, I should prefer the celebrated fronts of modern buildings, which have already received the approbation of all good judges. Such are the Galerie du Louire, the Garde Meubles, and two fronts of the Hotel de Salm."66 The Galerie du Louire (Figure 16), Garde Meubles (Figure 17), and the Hotel de Salm (Figure 18) are all buildings that Jefferson saw while living in Paris, which he considered to be the cultural center of Europe. All of these building are inspired with classical architectural features such as pediments, columns, and full entablatures. Even though Jefferson recommended these French buildings to L’Enfant, his own competitive design was based, significantly enough, on a different building. For his competitive design (Figure 19), Jefferson returned to Palladio, his "architectural bible," and the Italian architect’s most famous work, the Villa Rotunda (Figure 20) in Vicenza, Italy. Jefferson also had previously submitted the same design for the governor’s house in Richmond, but unsuccessfully. Jefferson described the site for the Villa Rotunda as "pleasant and delightful," yet "in the very city" which was similar to the location for the President’s House on the Potomac. The most striking similarity between Jefferson’s design and the Villa Rotunda were the four identical porticos that were attached to the building. In addition, Jefferson would again return to the idea of building a dome that would be composed of alternate segments of solid structures and glass in order to illuminate the room. As with the Capitol building, many doubted whether this idea could be practically executed, as it had been in the Halle au Bles in Paris.

Jefferson’s design was rejected for a few important reasons. First, it could not be easily extended because of the four identical porticos. Washington and the commissioners strongly believed that the President’s House would have to be extended or enlarged in the future because of the limited construction funds at the present time. Secondly, the interior design of the house, contained a mixture of public and private rooms, which would have made the President’s life chaotic. Some scholars have argued that Jefferson’s design was really a house for a country gentleman and not for a president. William Ryan and Desmond Guinness state:

La Rotunda was the home in

retirement for an aged and distinguished citizen.

It was his Monticello. The

President’s house, as the advertised program

emphasized, was to be the

nucleus of a great executive establishment for

the future. The basic dichotomy

of viewpoints was not successfully resolved

in Jefferson’s adaptation.67

Others scholars have argued that Jefferson’s design was not accepted because it may have been too advanced in both design and political ideology to win the competition at this point in American History.

The architect who won the competition was the Irish architect, James Hoban. Little is known about the background of James Hoban except that he trained in the Dublin Society architectural school and received a medal for excellence in drawing. He also worked on some of the finest buildings in Dublin, including the Newcomen Bank, and the Royal Exchange, which was designed by Thomas Cooley. Hoban’s design (Figures 21A & 21B) was classically inspired as evidenced by its classical features and adherence to the principles of Palladio. Hoban used all of the recommended ratios of Palladio in both the design and in the actual building of the President’s House. All of the rooms adhered to these ratios, even after Washington asked Hoban to expand his design by one-fifth. As Ryan and Guinness state, "Hoban’s treatment of the Ionic order is also in accord with classical rules. The proportions of the architrave, frieze, and cornice and the relation of the entablature to the height of the column (1:5) are all correct."68 The spacing between the columns on the façade also is classically correct because they follow the rules set down by Vitruvius. In the end, as William Ryan and Guinness state, "It shows the architect had been well-schooled in the geometric principles of Palladian design, and adhered closely to the rules laid down in The Four Books of Architecture."69

As the 18th Century came to a close, James Hoban had only completed a portion of the President’s House, and it remained unfinished when Jefferson took office. During the first two years of his term from 1801-1803, Jefferson did not have any architects work on the house; rather he wanted to get a feel for his surroundings. He still considered the mansion to be "big enough for two emperors, one Pope and the Grand Lama."70 In 1803, Jefferson and Benjamin Latrobe began to work on both the Capitol and the President’s House. Latrobe never really liked Hoban’s design, as he considered it to be a typical mid-eighteenth century English mansion with incorrectly proportioned entrances. When Latrobe arrived, he found the President’s House was largely unfinished and the grounds had not even been touched. The appearance of the President’s House not only bothered Latrobe, but it also affected Jefferson, who asked Latrobe to refine the towering, hulking, President’s House with a strong horizontal base and to add wings. Jefferson also wanted to add service quarters, stables, an icehouse, and a hen house, all to be built beneath a newly constructed terrace. Access to these outer parts of the house would be through classical colonnades or "covered ways." All of these measures would not only extend the space that was available in the house, but also, and more importantly, provide privacy for Jefferson who valued such greatly. Finally, Jefferson had the ground leveled in front of the President’s House, which provided a better view of the Potomac. Jefferson was an advocate of building a house that provided a magnificent view and was in hegemony with nature.

As with the Capitol, Jefferson and Latrobe often had minor disputes over the execution of the building. Latrobe wrote of the reason for many of the disputes in a letter to John Lenthall on May 3, 1805:

I am sorry I am cramped in

this design by his prejudices in favor of the old

French books, out of which

he fishes everything – but it is a small sacrifice

to my personal attachment

to him to humour him, and the less so, because the

style of colonnade he proposes

is exactly consistent with Hoban’s pile – a

litter of pigs worthy of

the great sow it surrounds & of the wild Irish boar…71

Even though Latrobe and Jefferson often squabbled they attempted to achieve the same goal as they sought in the Capitol building and often did work well together. One such instance was when they worked on the design of the most distinguishing features of the President’s House, the North and South Porticos (Figure 22). Although we can not be certain that Jefferson designed the curved South Portico, the evidence that does exist leads to that conclusion. This evidence is that of a light semicircle drawn on the South Portico of Hoban’s original (Figure 23) design. Fiske Kimball attributes this light semicircle, drawn in pencil, to Jefferson, as the pencil sketch is similar to Jefferson’s own first plan. Also, Jefferson was known for his interest and passion in the porticos of buildings such as the Maison Carree, the Pantheon, and the Villa Rotunda. The South Portico was completed in 1824, and the North Portico, which can be considered a porte-cochere or "covered driveway," was completed in 1829. As Jefferson intended, the addition of the North and South Porticos further distinguished the President’s House as a unique and powerful symbol. As William Seale states:

From a distance the White

House gained a new importance on the south. The

portico took some significance

away from the frothy effect of the heroic

pilasters and the window

hoods, which it decidedly crowds out, but it also

gave the White House individuality.72

When we step back and examine the early history of the President’s House, we must do so with an eye on classical antiquity. As with the Capitol, styles from ancient architecture, especially from the Roman and Greek democracies, were chosen because they seemed to be more appropriate for a newly formed democratic society, as the new republic attempted to break its political and cultural ties with the English monarchy and its governmental system. The President’s House has been a symbol and focal point of the government, along with evoking a strong passion from almost every American, just as Jefferson had hoped would happen, as David Gebhard explains, "If a building was reflective of the cultural values of the nation in which it was constructed and if it was beautiful, Jefferson contended that it would reinforce the ideals of that country, improve the taste of its citizens, and raise its esteem in the world’s eyes."73 The President’s House has always reflected the values of freedom and democracy, which not only reflect America, but the classical societies that inspired its designers.

Part VII: Conclusion

As we attempt to draw some final conclusions regarding the classically inspired civic architecture and political ideology that Jefferson so convincingly helped shape, we are left with a subject that operates on many different levels. First, there are the pure architectural characteristics that are exhibited in the features of such buildings as the Capitol Building in Richmond and the U.S. Capitol. As Horace M. Kallen states:

His concept of structure

called for a space, order and logic which to him

the antique exemplified…

His desire for these qualities in buildings

sprung from… the need, shall

we say, of great open spaces combining

order with freedom.74

Jefferson’s desire for freedom, controlled by order, did not end with architecture; rather these characteristics represented the goals of the new Republic as well, which Jefferson strove to communicate through its architecture.

Along with representing the political ideology of the new Republic, Jefferson’s architecture also serves a symbolic purpose, since it acts as a unifying agent for all citizens to be in a word, "Americans." When one citizen looks at the lasting impact of Jefferson’s architecture, the discussion should begin at this point. As Joshua Johns so eloquently states:

We have not become the feudal

agrarian society Jefferson envisioned,

nor have we achieved total

social control and harmony with nature, but

in many ways, his architecture

still tugs at our sense of history and

heritage—for better or for

worse—and his ideas continue to define what

is "American" in us: the

need to reinvent and reconstruct for our own

purposes, the desire for

a distinctive national identity, driven by an

inexplicable but powerful

yearning for order, simplicity, and centrality.75

Structures such as the Capitol and the President’s House serve as rallying

points for all

Americans to be unified.

In the end, though, the greatest importance that Jefferson’s civic architecture serves is that it can be the "shining light" that can lead America through its most difficult times. At age 15, after the death of his father, Jefferson went through one of the most challenging moments of his life. In response to these circumstances, Jefferson turned to the literature of classical antiquity as a way of dealing with these personal difficulties. To Jefferson and many of the founding fathers, classical antiquity provided strong guidance that would lead them through their lives. Jefferson knew the power of the classics and this is why he insisted on returning to this motif for the completion of the most important buildings in our young Republic. Just as the classical antiquity helped Jefferson get through his most challenging moments in life, it seems likely that Jefferson believed that these symbolic architectural masterpieces, engrained in the architecture of classical antiquity, could help the United States also work through its most difficult moments. One of these moments occurred in the middle of the 19th Century, during the Civil War, when the United States almost permanently split in half. Even under the pressures of war, Abraham Lincoln continued to push forth the completion of the Capitol dome and the placement of the bronze statue of "Freedom" (Figure 24) on it. As Jefferson had done, Lincoln also understood the importance of the Capitol to the unity and sustainability of the United States. During this period, Lincoln returned to the inspiration and symbolism of classical antiquity, as Jefferson once had. This time was different in some respects, however, in that Lincoln was not merely returning to Rome or Athens for inspiration, but he was returning to the days of Adams, Jefferson, and Washington, as a source of guidance and unity, with which all Americans could identify. In its deepest sense, this is the power and significance of America’s national classical architecture, and also of Thomas Jefferson, America’s premiere classical architect.

Bibliography

1. BOOKS:

Carter, Edward C. II, and John C. Van Horne, and Lee W. Formwalt, ed.

The Journals of Benjamin

Henry Latrobe: 1799-1820, vol. 3: "From

Philadelphia to New Orleans."

New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980.

Dumbauld, Edward. Thomas Jefferson, American Tourist. Norman:

University

of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson.

New York:

Vintage, 1996.

Gebhard, David, and Deborah Nevins. 200 Years of American Architectural

Drawing. New York:

Whitney Library of Design, 1977.

Hamlin, Talbot. Benjamin Henry Latrobe. New York: Oxford University Press, 1955.

Hazelton, George C. The National Capitol: Its Architecture, Art and

History.

New York: J.F. Taylor &

Company, 1902.

Kimball, Fiske. Thomas Jefferson: Architect. New York: DeCapo Press, 1968.

Kite, Elizabeth S. L'Enfant and Washington: 1791-1992. New York: Arno Press, 1970.

Library of Congress. The Capitol: symbol of freedom: a pictoral story

of the

Capitol in general and

the House of Representatives in particular.

Washington: U.S. Govt. Print.

Office, 1956.

Norton, Paul F. Latrobe, Jefferson, and the National Capitol. New York: Garland, 1977.

Padover, Saul, ed. Thomas Jefferson and the National Capitol. Preface

by

Harold L. Ickes. Washington,

D.C.: Government Printing Press, 1946.

Peterson, Merrill D., ed. Thomas Jefferson: A Profile. New York: Hill & Wang, 1967.

---. The Portable Thomas Jefferson. New York: Penguin, 1975.

Randall, William Sterne. Thomas Jefferson: A Life. New York: Holt, 1993.

Report of the Commission of the Renovation of the Executive Mansion.

Washington D.C.L GPO, 1960.

Rice, Howard C. Thomas Jefferson's Paris. Princeton: Princeton

University

Press, 1976.

Ryan, William and Desmond Guinness. The White House: An Architectural

History.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980.

Seale, William. The White House: The History of an American Idea.

Washington,

D.C.: American Institute

of Architects Press, 1992.

Whiffen, Marcus. The Public Buildings of Williamsburg. Williamsburg:

Colonial Williamsburg, 1958.

2. Articles:

Daiker, Virginia. "The Capitol of Jefferson and Latrobe." Quarterly

Journal of

the Library of Congress

32 (1975): 25-32.

Guinness, Desmond. "Thomas Jefferson: Visionary Architect." Horizon,

22

(1979): 51-55.

Kimball, Fiske. "Thomas Jefferson and the First Monument of the Classical

Revival in America." Journal

of the American Institute of Architects

(1915): vol. 3, no. 9.

Lancaster, Clay. "Jefferson’s Architectural Indebtedness to Robert

Morris."

Journal of the Society

of Architectural Historians (1951): vol. X,

no. 1: 3-10.

Suro, Dario. "Jefferson, The Architect." Americas 25 (1973):

29-35.

Waterman, Thomas. "Thomas Jefferson: His Early Works in Architecture."

Gazette des Beaux-arts

(1943): vol. XXIV: 89-106.

Woods, Mary N. "Thomas Jefferson and the University of Virginia: Planning

the Academic Village."

Journal of the Society of Architectural

Historians 44 (1985):

266-83.

3. Web Resources:

Johns, Joshua. "Thomas Jefferson: The Architect of a Nation." (March

1996).

on-line list: http://xroads.virginia.edu/~CAP/JEFF/jeffarch.html