Judith Chubb,

Political Science

Reflection

As is reflected

in the questions that follow, I am deep in an "intellectual discomfort zone,"

trying to work through how what we saw and heard in El Salvador relates to my

broader understanding of injustice, violence and peace-building. Visiting El

Salvador twenty years after the peace accords brought an end to the brutal

civil war, I struggle with what "peace" means in a situation like this. I keep

replaying in my mind Oscar Romero's statement that "a just peace isn't the

peace of the cemetery." What is the function of memory in El Salvador? Of

course, it is essential to preserve the memory of what happened for future

generations, and it may have therapeutic value for the victims to have their

pain acknowledged and validated, but I wonder whether public recognition of

martyrs (in symbolic actions like the Monument to Truth or the naming of

Monseñor Romero Boulevard) has become a substitute for justice to the

victims and the survivors. In the absence of perceived justice on the part of

the victims, is meaningful reconciliation possible? Can the society come to

terms with its past and move forward if there is no acceptance of

responsibility and no accountability for the perpetrators (not just physical

but political and moral) of the atrocities? The Truth Commission documented the

victims, but memory and history remain highly contested. Without

accountability, does memory keep open the wounds of the past, preventing the

society from coming together to move forward? And what do history and memory

mean for the new generations that never directly experienced the pain of the

war? Thirty years after the end of the war, would trials or other forms of

accountability serve any purpose or would they repolarize society? Is it better

to close the book on the past and move forward, as the general amnesty

attempted to do?

|

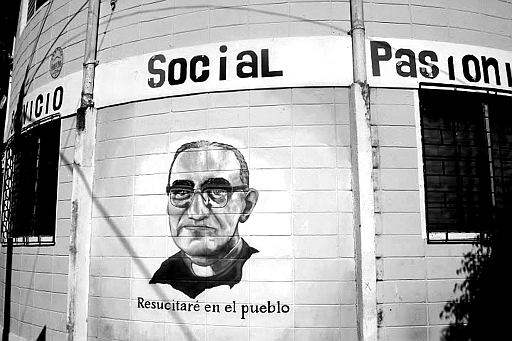

Recordatorio de Monseñor

Romero, Arzobispo de San Salvador,

asesinado el 24 de marzo de

1980

© Justin Poché, History |

What are the

prospects for building a more just society in El Salvador? The war was caused

by a highly polarized society and the refusal of established elites to consider

any type of political or economic reforms to provide a meaningful voice and

some measure of social justice to the poor peasants who constituted the

majority of the population. After 12 years of war and at least 79,000 civilian

victims, the two parties signed a peace accord, which put in place the

framework for the development of the country up to the present. The war ended,

the troops on both sides were demobilized, opposition parties were allowed to

organize and run for office, basic human rights were guaranteed, the Left even

came to power in 2009. However, the peace accords deliberately sidestepped all

issues of economic redistribution to focus solely on political inclusion, and

the guerrilla forces agreed to a neo-liberal economic structure as a condition

for the end to armed conflict. While democracy and respect for human rights are

certainly fundamental steps forward, does this agreement forestall deeper

social and economic changes in El Salvador? With regard to political power, how

much difference does ideology make if policy options are constrained within the

confines of existing economic structures? How much difference has political

participation made in the lives of those social groups who supported the

guerrillas? The "leftist" government has focused on populist policies like

providing milk, shoes and uniforms for schoolchildren rather than structural

change; it is increasingly trapped between the necessity for political and

economic compromise on the one hand and the frustrated expectations of its

supporters on the other.

Can El Salvador

today be considered a country "at peace" when gang violence has now reaped more

victims than 12 years of civil war? I was struck by the fact that the upsurge

in criminal violence apparently coincides with the signing of the peace

accords. What are the deeper causal factors at work here? Is it just a question

of U.S. deportation of criminals back to El Salvador? Why have criminal gangs

and organized crime found such a fertile terrain among marginalized youth? To

what extent is this a legacy of the failure to settle the social and economic

issues that gave rise to the civil war? Looking at the bigger picture, the

problem is not just the physical violence of the gangs, but the underlying

problems of structural violence (poverty, poor education, poor health care)

which the extreme levels of criminal violence at least in part reflect.

What then are the

prospects for meaningful change? In the absence of a shared public commitment

to change, have the underlying issues of poverty and inequality that drove the

civil war been "resolved" through mass emigration? Given the rather grim

picture of El Salvador's economic, social and human resources with which we

were presented, I find myself wondering if encouraging emigration may be the

most effective anti-poverty tool available to the government. The country needs

massive investment in human resources (especially education), infrastructure

and environmental protection. But where would the money come from? The current

"left-wing" government does not have a solid parliamentary majority, and it is

not even clear if it will remain in power after the next elections. Might

remittances be the most effective anti-poverty tool, because they don't require

sacrifice from existing elites? |