|

Defined as a complete enumeration of a population, census data can provide historians a very rare and important view into the past. While by no means perfect, census data provides an opportunity to contextualize other historical sources in offering a partial view of composition of a community, occupational status of its members, their income and property and family or household composition. Census data was also important for nineteenth-century town governments in determining constituencies and the relative social and economic status of their communities. Accordingly, a federal census was undertaken every ten years beginning in 1790 and starting in the antebellum period the Commonwealth of Massachusetts enumerated its citizens, also in ten-year intervals, beginning in 1855. One of the more interesting facets of Worcester census data from this period is documentation of the contours of the local African American community preceding the Civil War.

As is the case with any historical sources, a fundamental question if for whom a document is provided or what is the target audience. Clearly, census data was not recorded for local African Americans but for municipal, state and federal agencies. With state and federal censuses, there is some variation in information to be collected, however, all enumerations from this period include a resident’s name, age, race or color, gender, marital status, birthstate, and occupation. Some also gather information about value of real estate owned by an individual and a person’s cash assets as well as whether children attended school in the previous year or whether a couple had been married within the year.

It is worth noting, however, that in censuses of this period instructions to enumerators were sometimes vague, with the result that information collected reveals subjective assessments of those compiling the data. For example, information regarding race or color in these documents is inconsistent and often capricious; the terms “black” or “mulatto” are used for describing local African Americans, “mulatto” not indicating a person of mixed racial ancestry but someone of lighter pigmentation.

The censuses in question were taken between the years 1850 and 1860, a time when Worcester was undergoing substantial industrial and commercial growth and an African American community was firmly established as part of the city’s social landscape. For purposes of comparison a listing of Boston ’s African Americans from 1830 and a compilation of African Americans in New Bedford , Massachusetts federal census 1850 were also analyzed.

When one examines compilations from Worcester census data enumerating local people of color it becomes clear that in the period from 1850 through 1860 the African American community at Worcester not only grew in size but reflected a diversity of individuals and families settled in the area. Some were born in Worcester, the children and grandchildren of eighteenth-century slaves; others, also born in Worcester , were individuals of African American and Nipmuc Indian ancestry. In this decade, however, black Worcester expanded as individuals moved from more rural New England locations for employment in Worcester ’s developing industrial economy, and, for the first time in Worcester history, significant numbers of African Americans from southern states appear in local records.

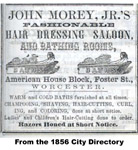

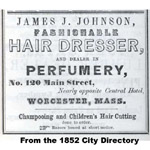

One of the most interesting aspects of this census data, however, is the occupations of people of color at Worcester, in the earlier nineteenth century most local African Americans earning a living as domestic servants and laborers. While these occupations persist in the 1850s, as seen with several African Americans recorded as part of a “white household” or listed as “laborer”, by 1860 black residents of Worcester of the community held a wider variety of jobs. Specifically, the most common of more specialized occupations was a barber or hair dresser.

Considered to be an honorable profession, barbering was the occupation of prominent members of African American  communities throughout New England , several ministers at Boston , Providence or Hartford earning their living as hairdressers or barbers. Not surprisingly, during the 1850s, all of the barber shops of Worcester were operated by African Americans. Men who owned these establishments are among African Americans owning real estate at Worcester ; they report cash assets to census enumerators; and, as is established by several researchers, black barbers of Worcester were community leaders involved in forming the first of local African American organizations. communities throughout New England , several ministers at Boston , Providence or Hartford earning their living as hairdressers or barbers. Not surprisingly, during the 1850s, all of the barber shops of Worcester were operated by African Americans. Men who owned these establishments are among African Americans owning real estate at Worcester ; they report cash assets to census enumerators; and, as is established by several researchers, black barbers of Worcester were community leaders involved in forming the first of local African American organizations.

For women of color of this period laundress is the dominant occupation and a majority of laundresses listed in Worcester city  directories of 1850s were African American. directories of 1850s were African American.

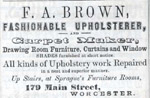

Starting in 1850, however, occupations like herb doctor, upholsterer and basketmaker are recorded for local people of color. By 1855 the census enumerates machinists, shoemakers, whitewashers and paperhangers among people of color. Finally, by 1860 occupations such as carpet cleaner, lecturer, used clothes salesman and daguerreotype maker are listed for African American males.

How did occupations in Worcester ’s African American community compare with those of New Bedford ’s black community? In 1850, for example, the New Bedford federal census demonstrates that an overwhelming majority of black  males were sailors. While there were a few “white household” designations at New Bedford , people of color seemed to hold more specialized jobs than Worcester at the same time. Among these occupations were soap maker, blacksmith, waiter and bootmaker, to cite a few examples. More varied occupations at New Bedford, however, are a reflection of that city’s diverse African American community where men of color were involved in multiple trades supporting New Bedford maritime industries much as Frederick Douglass could find employment there as a caulker in ship-building enterprises. males were sailors. While there were a few “white household” designations at New Bedford , people of color seemed to hold more specialized jobs than Worcester at the same time. Among these occupations were soap maker, blacksmith, waiter and bootmaker, to cite a few examples. More varied occupations at New Bedford, however, are a reflection of that city’s diverse African American community where men of color were involved in multiple trades supporting New Bedford maritime industries much as Frederick Douglass could find employment there as a caulker in ship-building enterprises.

An area in which both cities were comparable was age. Both New Bedford and Worcester were communities in which younger people of color outnumbered individuals between 30 and 50 years of age, as both locations were a destination of younger adults starting families.

While no census is perfect and they, undoubtedly, leave us with more questions than answers it is still possible to draw some general conclusions and observe trends based on the documentation provided. From the census data it becomes clear that the community of people of color in Worcester is in formation. While no census is perfect and they, undoubtedly, leave us with more questions than answers it is still possible to draw some general conclusions and observe trends based on the documentation provided. From the census data it becomes clear that the community of people of color in Worcester is in formation.

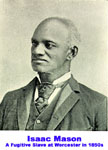

Interestingly, some individuals mentioned in the 1850 census with established occupations were not mentioned again in 1855, but re-appear in 1860. As Worcester resident Isaac Mason, author of a slave narrative, and former fugitive slave who sought refuge here, explained this is related to several African Americans leaving town with passage of the Fugitive Slave law of 1854, returning to Worcester only on the eve of the Civil War.

Census Data 1790

Census Data 1850

Census Data 1855

|