|

Introduction

Driving

down Grove Street today it is hard to miss the massive brick structure

known as Northworks, a mixed use office complex which is home to drafting

firms, restaurants, financial planners, accountants and numerous other

small businesses. Upon closer examination one reads the stone lettering

above the door at the 100 Grove Street entrance clearly spelling out Washburn

and Moen Manufacturing Company. Even to onlookers who know nothing of

this company's rich history and importance in the development of the city

of Worcester, the physical proportions and size of the building give off

the aura of something that was once a great industrial operation. This

assumption would most definitely be correct. Driving

down Grove Street today it is hard to miss the massive brick structure

known as Northworks, a mixed use office complex which is home to drafting

firms, restaurants, financial planners, accountants and numerous other

small businesses. Upon closer examination one reads the stone lettering

above the door at the 100 Grove Street entrance clearly spelling out Washburn

and Moen Manufacturing Company. Even to onlookers who know nothing of

this company's rich history and importance in the development of the city

of Worcester, the physical proportions and size of the building give off

the aura of something that was once a great industrial operation. This

assumption would most definitely be correct.

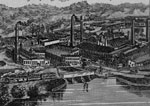

The

November 1902 issue of Worcester Magazine related that "the

largest single industry in Worcester is that of wire-making" (169).

Founded in 1831, Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company was the reason

for this. During its peak at the turn of the century Washburn and Moen,

which later became part of American Steel and Wire, operated three major

facilities in Worcester. Its headquarters was the Northworks Plant on

Grove Street. The Central Works was the smallest of the three plants and

was located downtown at the current location of the Centrum. The Southworks,

another large complex, was located in Quinsigamond Village in "the

crowing glory of Holy Cross College" (175). The factories made wire

of all shapes, sizes and styles. In the 1850s the company had perfected

the production of piano wire, thus making it the industry leader in its

production (175). Later in the 19th century Washburn and Moen produced

wire for hoop skirts, a fashion trend sweeping the country. Their production

expanded again when in the 1870s they purchased the patent rights to barbed

wire from its inventor Joseph Glidden (Barbed

Wire History Online). No matter what type of wire a customer needed,

Washburn and Moen would find a way to produce it. The

November 1902 issue of Worcester Magazine related that "the

largest single industry in Worcester is that of wire-making" (169).

Founded in 1831, Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company was the reason

for this. During its peak at the turn of the century Washburn and Moen,

which later became part of American Steel and Wire, operated three major

facilities in Worcester. Its headquarters was the Northworks Plant on

Grove Street. The Central Works was the smallest of the three plants and

was located downtown at the current location of the Centrum. The Southworks,

another large complex, was located in Quinsigamond Village in "the

crowing glory of Holy Cross College" (175). The factories made wire

of all shapes, sizes and styles. In the 1850s the company had perfected

the production of piano wire, thus making it the industry leader in its

production (175). Later in the 19th century Washburn and Moen produced

wire for hoop skirts, a fashion trend sweeping the country. Their production

expanded again when in the 1870s they purchased the patent rights to barbed

wire from its inventor Joseph Glidden (Barbed

Wire History Online). No matter what type of wire a customer needed,

Washburn and Moen would find a way to produce it.

Ichabod

Washburn

Ichabod

Washburn, one of the founders of the Worcester Mechanics Association and

principle donor of Mechanics Hall,

Memorial Hospital and Worcester Polytechnic Institutive, was one of the

city's first manufacturers when he opened up a ramrod shop in Worcester

in 1819. His son-in-law, Philip Moen, was a highly successful businessmen

who commanded respect from everyone that worked with him. The corporation

itself started from humble beginnings. Ichabod Wasburn is considered to

be the first individual to draw wire in Worcester, in a sense allowing

him to procure significant investments from creditors within the city,

including the notable Stephen Salisbury II (Nutt 60). By 1831 Washburn

had begun the production of wire within a factory on School Street in

a partnership with Benjamin Goddard. A few years later Goddard left the

partnership and Washburn oversaw the construction of a building designed

solely for the production of wire (Worcester Magazine 175). For

a number of years Washburn's Wire Firm was operated jointly with his brother,

but by 1851 Philip Moen, Ichabod Washburn's son in law, was taken on as

a partner. It was this partnership that truly allowed the business to

flourish. Ichabod

Washburn, one of the founders of the Worcester Mechanics Association and

principle donor of Mechanics Hall,

Memorial Hospital and Worcester Polytechnic Institutive, was one of the

city's first manufacturers when he opened up a ramrod shop in Worcester

in 1819. His son-in-law, Philip Moen, was a highly successful businessmen

who commanded respect from everyone that worked with him. The corporation

itself started from humble beginnings. Ichabod Wasburn is considered to

be the first individual to draw wire in Worcester, in a sense allowing

him to procure significant investments from creditors within the city,

including the notable Stephen Salisbury II (Nutt 60). By 1831 Washburn

had begun the production of wire within a factory on School Street in

a partnership with Benjamin Goddard. A few years later Goddard left the

partnership and Washburn oversaw the construction of a building designed

solely for the production of wire (Worcester Magazine 175). For

a number of years Washburn's Wire Firm was operated jointly with his brother,

but by 1851 Philip Moen, Ichabod Washburn's son in law, was taken on as

a partner. It was this partnership that truly allowed the business to

flourish.

The

Firm's Success

By 1863 the firm began

to operate their own cotton mill in order to produce enough yarn to cover

the daily production of wire (Nutt 61). In 1889 over 3,000 workers were

employed within the company's three plants and it was officially the largest

employer in Worcester.  When

Washburn and Moen became part of the American Steel and Wire Company in

1899 it was the final piece in creating the largest Wire conglomeration

in the United States. At the time, it was the largest company the nation

had ever seen (Nutt 30). In this period of great prosperity for the firm,

over 200,000 workers were employed in the Worcester facilities, most of

them at Northworks. The Worcester plants remained strong until increased

competition from southern manufacturers drove US Steel, American Steel

and Wire's successor, to restrict operations. By 1972 company reports

declared the Worcester plants to be "marginal" and, ultimately,

they were closed by 1978 (Smith Online). When

Washburn and Moen became part of the American Steel and Wire Company in

1899 it was the final piece in creating the largest Wire conglomeration

in the United States. At the time, it was the largest company the nation

had ever seen (Nutt 30). In this period of great prosperity for the firm,

over 200,000 workers were employed in the Worcester facilities, most of

them at Northworks. The Worcester plants remained strong until increased

competition from southern manufacturers drove US Steel, American Steel

and Wire's successor, to restrict operations. By 1972 company reports

declared the Worcester plants to be "marginal" and, ultimately,

they were closed by 1978 (Smith Online).

As

his wire manufacturing company was being established, Ichabod Washburn

was also establishing himself as an effective and well respected businessman

within the Worcester community. He was the deacon of his church and contributed

greatly to cultural institutions (Nutt 62). He truly loved the city and

the city loved him back. His partner and son-in-law Philip Moen was held

in equally high esteem, viewed by those who worked with him as "kind,

courteous and frank," and proved a worthy successor to Washburn when

he passed away (Nutt 30). Moen was also involved in the community at large,

working as a trustee of two banks, the Memorial Hospital and the Home

for Aged Men. The respect commanded by these two men within the community

prompted Worcester to be willing to work with Washburn and Moen Manufacturing

in order to assure its continued success. After all, it seemed that what

was good for Washburn and Moen was good for Worcester. As

his wire manufacturing company was being established, Ichabod Washburn

was also establishing himself as an effective and well respected businessman

within the Worcester community. He was the deacon of his church and contributed

greatly to cultural institutions (Nutt 62). He truly loved the city and

the city loved him back. His partner and son-in-law Philip Moen was held

in equally high esteem, viewed by those who worked with him as "kind,

courteous and frank," and proved a worthy successor to Washburn when

he passed away (Nutt 30). Moen was also involved in the community at large,

working as a trustee of two banks, the Memorial Hospital and the Home

for Aged Men. The respect commanded by these two men within the community

prompted Worcester to be willing to work with Washburn and Moen Manufacturing

in order to assure its continued success. After all, it seemed that what

was good for Washburn and Moen was good for Worcester.

What

made the Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company such a powerhouse within

Worcester? While there were many factors involved, one of the most important

was innovation. In addition to the steady flow of capital guaranteed from

buyers of their wire, civic cooperation made constant experimentation

with new techniques and manufacturing methods possible. They were the

first company to have continuous tempering of wire, devised the most effective

method of producing telegraph wire, and were one of the few only companies

in the nation to produce corset wire (Worcester Magazine 177).

Washburn and Moen truly demonstrated the importance of research and development

in having a successful business. Even in its later years, it was such

innovation that kept American Steel and Wire one step ahead, carrying

on the rich legacy established by Washburn and Moen. What

made the Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company such a powerhouse within

Worcester? While there were many factors involved, one of the most important

was innovation. In addition to the steady flow of capital guaranteed from

buyers of their wire, civic cooperation made constant experimentation

with new techniques and manufacturing methods possible. They were the

first company to have continuous tempering of wire, devised the most effective

method of producing telegraph wire, and were one of the few only companies

in the nation to produce corset wire (Worcester Magazine 177).

Washburn and Moen truly demonstrated the importance of research and development

in having a successful business. Even in its later years, it was such

innovation that kept American Steel and Wire one step ahead, carrying

on the rich legacy established by Washburn and Moen.

Worcester's

Immigrant Workforce

When immigrant groups

came to Worcester they inevitably came to the wire factories to look for

work. As the largest industry in Worcester, it offered thousands of immigrants

employment in one of the company's three plants. Living in three-deckers

around the city, specifically Irish, French and Swedish immigrant groups

found work during one of the 8-hour shifts (Smith Online). In later years

many Armenian and Turkish immigrants also would find work alongside the

Europeans, making the factory a "veritable Babel" (Worcester

Magazine 178). Working in a Wire Mill was not a skilled occupation,

thus no formal education was necessary. This made it an ideal job for

immigrants to the city. Washburn and Moen was particularly important for

Swedish immigrant groups. Moen had studied in Sweden in his younger years

and, observing the work ethic of the Swedish people, he actively recruited

a number of Swedish workers to come to Worcester to staff his factories

(Anderson Interview).  This

was particularly true in the Quinsigamond Village Southworks plant. Amos

Webber, a janitor and messenger in the factory, even points out that women

were employed by Washburn and Moen in their fine wire operations (Salvatore

299). Nearly every group within Worcester could find employment within

these factories. This did not mean, however, an absence of friction over

jobs and working conditions. Accidents were frequent and all the plants

required a full service emergency ward and "competent surgeon"

(Worcester Magazine 180). Undoubtedly the working conditions left much

to be desired as well. Strikes were commonplace as they were at most large

corporations at the time. Newspaper accounts suggest that labor was dealt

with respectfully by the administration. This

was particularly true in the Quinsigamond Village Southworks plant. Amos

Webber, a janitor and messenger in the factory, even points out that women

were employed by Washburn and Moen in their fine wire operations (Salvatore

299). Nearly every group within Worcester could find employment within

these factories. This did not mean, however, an absence of friction over

jobs and working conditions. Accidents were frequent and all the plants

required a full service emergency ward and "competent surgeon"

(Worcester Magazine 180). Undoubtedly the working conditions left much

to be desired as well. Strikes were commonplace as they were at most large

corporations at the time. Newspaper accounts suggest that labor was dealt

with respectfully by the administration.

Architectural

Structure

The

main structure's extensive façade runs for over 500 feet along

Grove street, a wave of red brick which sits just a few feet back from

the street. The main façade can be broken down into three main

sections: a long rectangular area on the left, a tripartite rectangular

section right of center, and a smaller rectangle to the far right. The

leftmost section is a seemingly endless expanse of brick and large three-pane

rectangular windows. The windows are spaced apart by solid brick areas,

forming a pattern that repeats itself almost identically for three stories.

Below each window is a concrete ledge, highlighting where the base of

the glass meets the brick that surrounds it. Above the third-story bank

of windows are decorative brick arches which mirror both the tops of the

windows and the brick spaces between them. A step higher above this arch

work is a decorative brick dentil frieze and cornice, which terminates

at the flat roof of the structure. The

main structure's extensive façade runs for over 500 feet along

Grove street, a wave of red brick which sits just a few feet back from

the street. The main façade can be broken down into three main

sections: a long rectangular area on the left, a tripartite rectangular

section right of center, and a smaller rectangle to the far right. The

leftmost section is a seemingly endless expanse of brick and large three-pane

rectangular windows. The windows are spaced apart by solid brick areas,

forming a pattern that repeats itself almost identically for three stories.

Below each window is a concrete ledge, highlighting where the base of

the glass meets the brick that surrounds it. Above the third-story bank

of windows are decorative brick arches which mirror both the tops of the

windows and the brick spaces between them. A step higher above this arch

work is a decorative brick dentil frieze and cornice, which terminates

at the flat roof of the structure.

To the right of this

long expanse and slightly forward is the four-story central entrance area

of the building, broken down into three vertical rectangles. The central

rectangle is the thinnest and tallest, featuring inlaid concrete strips

with the words "Washburn & Moen Manuf'g Co." and "Established

1831."

Set

in to the brick just under the roofline, are decorative cast-iron rectangles,

the only complex detail work that the façade features. This section

also features the same three-pane windows and decorative brickwork as

the left side of the structure, and is flanked by two stouter rectangles

with similar window and brick detail arrangement. The final section of

the façade was a later addition, and features a slightly different

brick color, while keeping a similar window arrangement and brick detailing.

One noticeable difference about this section is that the first three floors

of windows are recessed in vertical strips, set back from the surrounding

brick, while the fourth floor remains flush. Set

in to the brick just under the roofline, are decorative cast-iron rectangles,

the only complex detail work that the façade features. This section

also features the same three-pane windows and decorative brickwork as

the left side of the structure, and is flanked by two stouter rectangles

with similar window and brick detail arrangement. The final section of

the façade was a later addition, and features a slightly different

brick color, while keeping a similar window arrangement and brick detailing.

One noticeable difference about this section is that the first three floors

of windows are recessed in vertical strips, set back from the surrounding

brick, while the fourth floor remains flush.

The Northworks complex

is comprised of several other buildings as well, and is described in Worcester's

Best as follows:

"In all, the

Northworks includes three groups of buildings and one small detached

building built between 1863 and the early 1930s. The area occupies a

trapezoidal shaped lot bounded on the west by Grove Street, on the east

by Prescott Street, on the north by modern warehouses (occupying the

site of a Washburn and Moen barbed wire factory), and on the south by

parking lots where once stood the company's annealing house"

(21).

The

style of these other buildings is similar to that of the main building,

with little ornament, extensive amounts of red brick, and the same simple

two or three pane vertical windows. This industrial architecture is repeated

in many locations throughout the city.The Whittall

Carpet Mills in South Worcester, 1880-1910, for example, embody the

same powerful massing and rich brick textures. Repetition is a strong

design component, as is the underlying structure of angular geometry.

The buildings exhibit very few organic elements, and are primarily comprised

of right angles. The majority of the work on the structure was done between

1863 and 1870, and features elements of the Italianate style. The overhanging

eaves, decorative brackets, and slightly arched tall windows of the central

entrance area are all typical of this architectural style. There also

existed originally above the entrance a slightly rounded cupola which

was commonplace on Italianate structures. The rightmost section of the

façade, which was later renovated, once feature a mansard roof

typical of the Second Empire style, which became popular slightly after

Italianate. The

style of these other buildings is similar to that of the main building,

with little ornament, extensive amounts of red brick, and the same simple

two or three pane vertical windows. This industrial architecture is repeated

in many locations throughout the city.The Whittall

Carpet Mills in South Worcester, 1880-1910, for example, embody the

same powerful massing and rich brick textures. Repetition is a strong

design component, as is the underlying structure of angular geometry.

The buildings exhibit very few organic elements, and are primarily comprised

of right angles. The majority of the work on the structure was done between

1863 and 1870, and features elements of the Italianate style. The overhanging

eaves, decorative brackets, and slightly arched tall windows of the central

entrance area are all typical of this architectural style. There also

existed originally above the entrance a slightly rounded cupola which

was commonplace on Italianate structures. The rightmost section of the

façade, which was later renovated, once feature a mansard roof

typical of the Second Empire style, which became popular slightly after

Italianate.

Restructuring

Today

While

the majority of the Washburn and Moen buildings have been destroyed the

remaining structures have found new life. With tenants like physicians,

small scale industry, restaurants and a number of other private offices,

the Northworks continues to be a vital and important place within the

city of Worcester. Recently restoration work and modernization keep the

building market competitive. Floors have been refurbished, beams reinforced

and windows replaced in order to bring new tenants into the complex. While

the majority of the Washburn and Moen buildings have been destroyed the

remaining structures have found new life. With tenants like physicians,

small scale industry, restaurants and a number of other private offices,

the Northworks continues to be a vital and important place within the

city of Worcester. Recently restoration work and modernization keep the

building market competitive. Floors have been refurbished, beams reinforced

and windows replaced in order to bring new tenants into the complex.

Within

the doors of the central block, an elegant wooden staircase leads up to

the second floor. Dark wooden banisters are supported by ornate iron braces

and lead up on one side to a carved wooden newel post. Highly glossed

wooden floors are present throughout most of the building, with the exception

being concrete in the basement areas. The wear and age of the boards only

serves to make them more appealing, and gives the interior a slightly

rustic feel. Thick wooden columns and beams are present throughout the

building supporting the levels above, and exposed pipes can be seen running

along the wooden ceilings. Within

the doors of the central block, an elegant wooden staircase leads up to

the second floor. Dark wooden banisters are supported by ornate iron braces

and lead up on one side to a carved wooden newel post. Highly glossed

wooden floors are present throughout most of the building, with the exception

being concrete in the basement areas. The wear and age of the boards only

serves to make them more appealing, and gives the interior a slightly

rustic feel. Thick wooden columns and beams are present throughout the

building supporting the levels above, and exposed pipes can be seen running

along the wooden ceilings.  The

interior has been sectioned off by white walls with wooden wainscoting,

resulting in a maze-like interior that winds and turns along the length

of the structure. An original elevator is still present, featuring a metal

Greek key design along the top of the interior and manual sliding doors.

There is also an original vault in one of the interior brick walls that

is now used for storage. The

interior has been sectioned off by white walls with wooden wainscoting,

resulting in a maze-like interior that winds and turns along the length

of the structure. An original elevator is still present, featuring a metal

Greek key design along the top of the interior and manual sliding doors.

There is also an original vault in one of the interior brick walls that

is now used for storage.

Despite the modern

renovations to the interior, the building still maintains its character

and many original elements and details. A testament to progress at its

inception, Northworks has evolved and continues to function as an important

site in Worcester today while not abandoning its origins. The building

stands as a monument to a process that gave many of the city's citizens

and their descendants their first chance in the new country.

Bibliography

Anderson, John B.

Personal Interview.

"Barbed Wire History." Online: Available

http://www.barbwiremuseum.com/barbedwirehistory.htm.

Knowlton, Elliot B, and Gibson-Quigley, Sandra. Worcester's Best: A

Guide to the City's Architectural Heritage (Second Ed., Expanded and

Revised) Preservation Worcester: Worcester, 1996: 21-22

Paradis, Tom, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Planning,

and Recreation, Northern Arizona University, "Italianate Architecture"

http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~twp/architecture/italianate/

"Second Empire Architecture" http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~twp/architecture/secondempire/

Nutt, Charles. History of Worcester and Its People. 4 Vols. (New

York, NY: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1919) Vol 3.

Salvatore, Nick. We All Got History. (New York, NY: Times Books,

1996).

Smith, Patricia. "The Glory Days of American Steel and Wire."

Online: Available

http://www.assumption.edu/utc/summer2002/THE%20GLORY%20DAY2.htm.

"The Making of Wire." The Worcester Magazine. Vol 1V,

#5 (November 1902).

Whiffen, Marcus, American Architecture since 1780: A Guide to the Styles,

Rev. ed. Cambridge Mass. MIT Press, 1992.

|