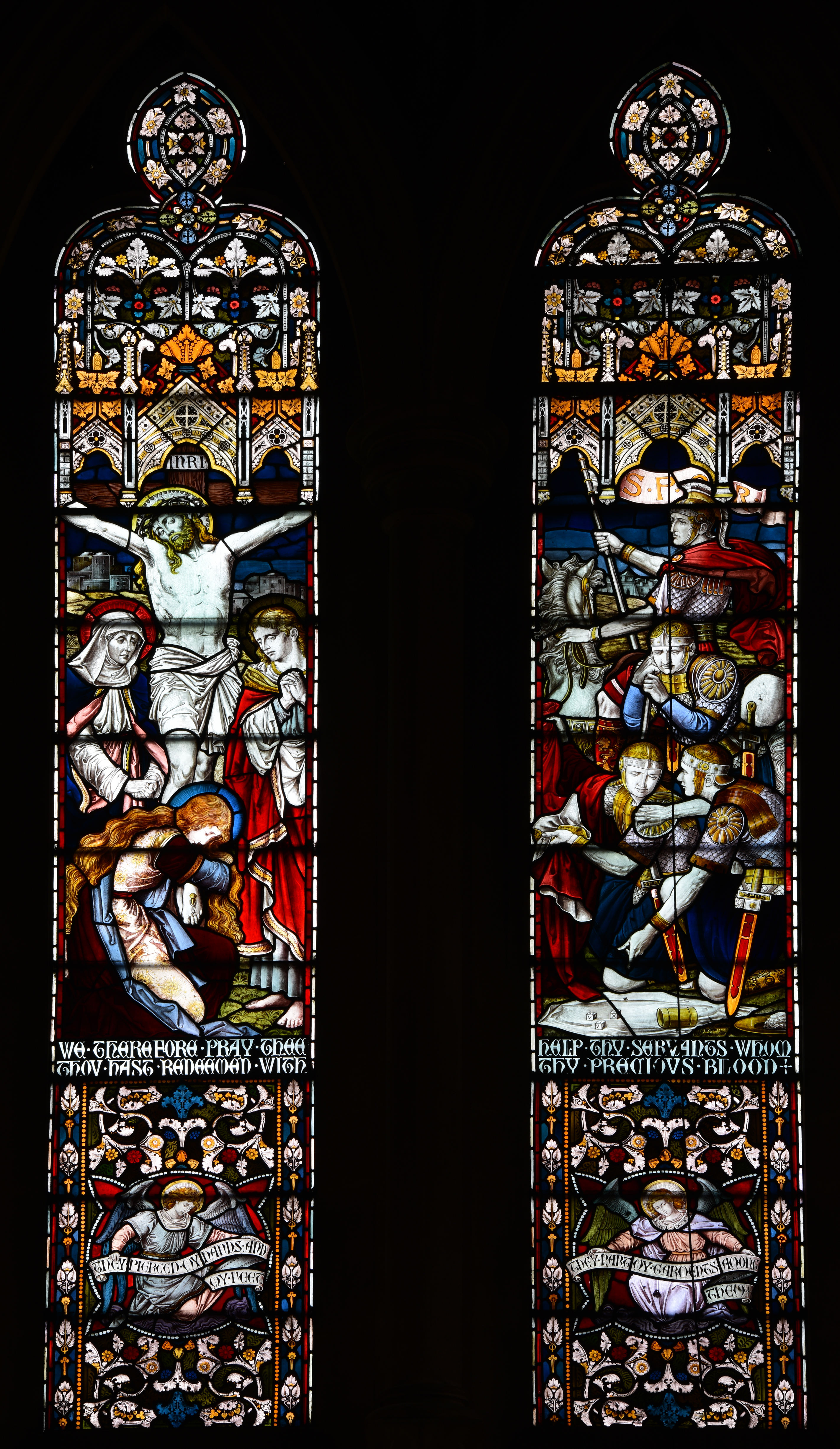

Henry Sharp Studio,

Good Shepherd, 1863, St.

Anna’s Chapel, St. Paul’s

Episcopal Church,

Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Photo: author The Studio of Henry E. Sharp, New York

An examination of the models and the patronage for commissions by Henry E. Sharp of New

Powell and Sons, London,

Apostles John and Thomas, 1859,

Digby Chantry, Church of St. Augustine,

Ramsgate, England.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinYork illuminates the relationship between the American artist in glass and English tradition in America. The Sharp studio was a long-lived and prolific enterprise, producing windows from about 1850 to 1897.1 Sharp’s windows are profoundly architectural, emphasizing deeply saturated color combined with uncolored glass and the relief of the figure against textured grounds. Often the European studios remain so connected to easel painting that the imagery operated more like tapestries, lying, however brilliantly, flat on the wall. Sharp’s simpler and intense designs, while arguable less sophistication in modeling, seem to leap out from the wall to intersect with the structure of the building. Complete ensembles such as the windows as in the First Universalist church in Providence, Rhode Island [See Appendix], or substantially preserved such as the Episcopal Cathedral of Pittsburgh, St. Paul’s Church of Wallingford and the Church of the Good Shepherd, Hartford Connecticut, or St. Anna’s Chapel, Newburyport, Massachusetts demonstrated the synergy of architecture and glass.2

A single figure, such as that of Sharp’s Good Shepherd (often reused) in St. Anna’s at Newburyport, presents the figure in brilliant chartreuse and red robe against an intense blue damascene ground. 3 The disposition is similar to that found in English production, such as figures of St. John the Evangelist and St. Thomas in the Digby Chantry at St. Augustine’s Ramsgate. St Augustine was the church of August N.W. Pugin, so that the selection of James Powell and Sons, signaled approval that the window was inspired by medieval principles.4 The glass, in turn, was inspired by English 14th-century examples of the Decorated Style, such as that of Selby Abbey. Similar patterns appear in a window Sharp considered one his most important productions, the Colt

Henry Sharp Studio, Good

Shepherd and Joseph in Egypt,

1868. Colt Memorial window,

Church of the Good Shepherd,

Hartford, Connecticut. After H.

Hudson Holly, Church

Architecture (1871), p. 270. Memorial window in the Church of the Good Shepherd in Hartford, illustrated in H. Hudson Holly's Church Architecture of 1870. 5 Typical of 19th-century production, Sharp's figures engage in a more awkward dialogue between the three-dimensional space of their robes and the flatness of the architecture. The vigor of the American window's brilliant color, retaining but intensifying the English gold, blue, and white harmonies, amply compensate for any faults in draftsmanship. In the Colt Memorial window, richness of surface decoration with intertwined foliage is reminiscent of the lacy forms of Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill.

Grisaille windows a standard aspect of decorative programs

Non-figural designs were a standard aspect of Sharp's production, as they were for the

York Minster, Grisaille window from the

vestibule leading to the Chapter House,

about 1280. Photo: author windows carried in English studio catalogs. Sharp installed fourteen double-lancet windows and a rose using a simple quarry design for Richard Upjohn's Bowdoin College chapel, Maine, in 1850, happily still extant.6 The 1860 catalog of Heaton & Butler, London, advertised fourteen varieties of "geometrical lead work, glazed in strong lead, and in any tint of Cathedral glass with coloured borders, and occasional pieces of colour." A second plate showed ten choices of grisaille glass:

Grisaille and ornamental quarry glass is now favourably received as a decoration for the aisle and clerestory windows of churches, especially when subdued light is required. The general effect is warm and silvery, and, when a little color is added, it is a most pleasing decoration. Grisaille glass often forms the groundwork for a window in which subjects, figures, or heraldry are introduced . . . This treatment will afford

Heaton & Butler, London,

grisaille pattern windows,

1860 catalog. all the color that is requisite, at an inconsiderable expense."

In the catalogs for Cox & Son, London, of 1870 and 1872, most of the choices are non-figural, with a variety of quarry designs in lattice systems of vertical or diagonal formats. Often the windows were provided with a figural or pattern inserts. One design of diagonal format, interspersing lines of text and stenciled foliate pattern quarries is based on 15th century

Grisaille

windows, Cox & Son,

28 & 29

Southampton

Street, London,

catalog of 1870

and 1872Tudor windows similar to those found in the great Hall at Ockwells manor, mentioned earlier.7 In this discussion, we should return to the very first windows in America, and a review of the value of non-figural glass advocated by John Henry Hopkins, Episcopal Bishop of Vermont. The mixture of color and the so-call blank glazing was standard throughout the Middle Ages. At York Minster, the vestibule leading to the Chapter House presented a series of tall grisaille lancets intersperses with heraldic shields. Installed about 1280, the windows bring considerable light into the interior.

Sharp invariably used the "favourably received" grisaille and ornamental quarry glass in aisle and clerestory. An aisle window dedicated to the memory of Mrs. Sylvia Hall, for St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Wallingford, dates from

Henry Sharp Studio,

Silver-stain quarries

and diagonal

inscription bands,

1868, Memorial to

Mrs. Sylvia Hall,

St. Paul's Episcopal

Church, Wallingford,

Connecticut.

Photo: author

1868.8 Its verses “Blessed are they which die in the Lord” are carried on white glass bordered in blue diagonal bands throughout the window, alternating with quarries of silver-stain fleur-de-lis against white glass. Cox’s catalog reads “Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord.” Sharp's technique is similar to his English counterparts. Often the quarries are stenciled in a flat application of grisaille paint. Like the English glass painter, Sharp relieved the design, frequently a stylized flower or leaf, by a tiny grid pattern in the background.

Henry Sharp Studio, Apostles, John,

Peter, Paul and James the Less, 1868,

chancel window, St. Paul's Episcopal Church,

Wallingford, Connecticut. Photo: author A mixture of color and grisaille in Providence, Wallingford, and Hartford

Chancel and choir loft, and frequently transept windows provide color drenched cross axes for the church. In Wallingford, for example the brilliantly colored entrance rose speaks to the chancel program of four lancets showing John the Evangelist, Paul, Peter, and James the Less. The sources for these figures testify to the narrow but seemingly universal iconographic canon of the 19th -century religious imager. The Apostles are modeled closely after the inventions of Friedrich Overbeck, a founder of the Nazarene movement of Catholic art in Bavaria, discussed later in the context of European imports in the latter 19th cenutry.9 Such images were widely distributed in single sheets and bound collections. Peter and James the Less are exact reproductions; John shows the same stance of open book and eagle at feet, but is given a youthful face (thus referencing the young disciple, not the bearded author of the Book of

Friedrich Overbeck, Apostles

Peter and James the Less, 1842-53,

prints by Franz Keller, distributed

through the Dusseldorf Union for the

Promotion of Good Religious Pictures.

After Religiöse Graphik aus der Zeit

des Kölner Dombaus 1842-1880

[exh. cat., Diocesan Museum]

(Cologne, 1980).Revelations); Paul is from another source. Likewise, in the First Universalist window of the four evangelists, Matthew and Luke are exact copies of Overbeck designs; John shows the same youthful face, and Mark is from another source.

Henry Sharp Studio, Apostles, Mathew,

Luke, Mark, John: the Four Evangelists,

1871-72, west window, First Unitarian

Universalist Church, Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinSimilarly, in the chancel of the Church of the Good Shepherd, Hartford, Christ stands in the center of the twelve apostles. All except the images of Christ and St. John to his right are exact reproductions of the Overbeck series. 10

Figural work displayed the cutting edge of a studio's expertise and demanded the highest prices per square foot. In 1867, Sharp designed a window of female personifications of Faith and Hope, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was originally set in James Renwick’s (Renwick and Sands) St. Ann's Episcopal Church, in Brooklyn, no longer a house of worship.11 Heaton and Butler's catalog prices of 1860 clearly articulate contemporary studio evaluation of time and materials. The cost of a grisaille patterned window with a medallion insert varied

After plans by H. Hudson Holly,

First Unitarian Universalist Church,

1871-72, Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinfrom three shillings sixpence to around six shillings. The Acts of Mercy window, a window of six different figural scenes executed for St. Nicholas' Church Harpenden and exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1862, sold for about thirty shillings a square foot.

Henry Sharp at First Universalist Church, Providence

Sharp appears to have been the studio of choice for architects such as Richard Upjohn, Rufus Sargent, Edward Tuckerman Potter, responsible for the Church of the Good Shepherd and the lavish home of Samuel Clemens, both in Hartford, and H. Hudson Holly of New York, the designer of the First Universalist church.12 In 1870, the Providence congregation was offered $101,500 for their old church building of about 1825 as its location became sought after by neighboring industries. The extraordinary profits of the sale allowed the First Universalists to build in their estimate "the finest church possible" at a total cost of $133,492 (a considerable sum in 1871-1872 America). The decorative and structural elements of the building were conceived as a whole. The architect was a strong

Henry Sharp Studio,

aisle window, 1871-72, First

Unitarian Universalist Church,

Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinsupporter of the use of stained glass as a means of introducing color into architecture. AA2.18 He referred to stained glass as a "noble

Henry Sharp Studio,

detail of grisaille in side

window, 1871-72, Trinity

Cathedral, Episcopal,

Pittsburgh. Photo: author and appropriate adornment" and believed that a building remained "a mere architectural outline" without the animation of "its somber masses through the spirituelle and enlivening influences of color."13 The windows were not dependent on individual donors but commissioned by the building committee and installed as a coordinated whole.

The aisle windows have lost a good deal of their stenciled patterns but the colors structure an interactive worship space. Similar designs appear in the aisles of Trinity Cathedral in Pittsburgh; the same elongated quatrefoil around a circle inscribed with a Maltese Cross. Red and green petals sprout at the sides. The stenciled leaf pattern is better preserved at Trinity. At the top, the hand-painted replaced panel on white glass demonstrates the subtlety of Sharp’s work. The original leaves, even faded, give much more of a sense of organic life and three-dimensional volume.

European windows executed in enamels integrated into the Providence building

The unusual glazing of the chancel window at the First Universalist church suggests a contrast of imported and domestic work. A story has come down through the years that sometime during the planning stages, members of the building committee were presented with an opportunity to buy windows reputedly created by a London studio for a Lutheran church in the United States. The Lutherans appear to have been unable to pay for the windows, and the First Universalists relieved the Lutherans of their debt by purchasing them. No records, however, have surfaced verifying the

Unidentified European

Studio and Henry Sharp? chancel

window, 1871-72, First Unitarian

Universalist Church, Providence,

Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinstory, nor are there accounts describing the selection or integration of any of the

William Peckitt,

Abraham, south

transept, York Minster,

1793.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinother windows of the church. We do have, fortunately, letters written by H. E. Sharp requesting payment and a newspaper article written 21 November 1872 following the dedication of the church, citing H. E. Sharp & Son of New York as the suppliers of the stained glass. 14

Stylistic analysis of the chancel glass reveals two types of painting. One repeats Sharp's established work as we know it from the Wallingford and Hartford commissions; the other shows figural types, modeling, and enamel techniques similar to those produced in Europe. Although clearly dating to the 19th century, the enamel glass recalls the windows by the widely respected William Peckitt of York (1731-1795). 15 Peckitt’s great south transept of York Minster of shows meticulous finish and three-dimensional naturalism; the paint is quite well preserved. The use of enamels was widespread in the latter Middle-Ages and Renaissance, especially for small-scale work. 16

If we accept this hypothesis, it is very likely that the imported work was perceived as superior.17 Not only did Sharp feel compelled to incorporate the glass into his own designs, but to set the panels in the most prestigious location

Unidentified European Studio

and Henry Sharp? detail of Christ and

the Children, chancel window,

1871-72, First Unitarian Universalist

Church, Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinwithin the church. In fact, the in-house publication of the church was entitled The Chancel Window. Sharp's task with this bay was to fit the panels into the preexisting framework of the sanctuary tracery. The lancets, which depict the Nativity, Christ as the Good Shepherd, Christ among the Children, and the Crucifixion, were apparently designed for a wider and possibly slightly longer space. Sharp cropped these panels at their sides, and he modified or more probably introduced the

Unidentified European Studio

and Henry Sharp? Angel, chancel

window, 1871-72, First Unitarian

Universalist Church, Providence,

Rhode Island. Photo: Michel M. RaguinGothic canopies framing each scene. The four angels below each lancet were also produced by the English workshop. These panels, however, were too narrow for the new space and Sharp extended each window by introducing a blue and yellow fleur-de-lys border .The transept image of the Conversion of St. Paul is also presumably from this source. Sharp surrounded it with pot-metal quatrefoils containing attributes of the Apostles.

Stylistic Fusion: new expressions for an American Studio

After adapting the “English” glass to its position in the chancel, Sharp was left with the problem of filling the large rose above the lancets. He had to rely on his own workmanship. For the quatrefoils and small triangular lights,

Unidentified European Studio

and Henry Sharp? transept window,

Conversion of St. Paul, 1871-72, First

Unitarian Universalist Church,

Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinSharp was able to adhere to the essentially two-dimensional and coloristic designs he had produced

Henry Sharp Studio, Ascension,

1871-72, chancel window, First Unitarian

Universalist Church, Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinelsewhere in the church. These panels pick up the luminous pot metal colors he had used to flesh out the English glass. For the large rose window, which was to complete the iconographic scheme of the chancel with a depiction of Christ's Ascension, Sharp felt compelled to produce an image that would correspond with the figural style of the four lancets.

It may be argued that Sharp took advantage of the situation to introduce new ideas into his own work. He apparently made working drawings from the imported glass, something quite simple to do on the workbench. He then used these models to construct the figures in the Ascension. Showing close similarities in size, proportions, pose, and facial characteristics, they are quite different in technique. Although the execution of the Ascension lacks the technical fluency of the original English draftsmanship, Sharp's ability to synthesize quickly the essentials needed for his design is apparent.

Trinity Cathedral, Episcopal,

Pittsburgh, interior looking towards chancel,

1869-72. Photo: authorContemporaneous: stained glass of Trinity Cathedral, Pittsburgh.jpg)

Henry Sharp Studio,

West window, Transfiguration

flanked by Matthew, Mark, Luke

and John; Shield of Faith

(diagram of the Trinity) in rose,

1871-72, Trinity Cathedral,

Episcopal, Pittsburgh.

Photo: author

Trinity Cathedral’s present building was begun in 1869 and completed in 1872. As the Diocese of Pittsburgh had been created only in 1865, the church was intended to be an appropriately dignified and beautiful structure. Built of Red Massillon sandstone, its pews are of white mahogany and Minton tiles decorate the floor. Windows from a New York firm popular with architects of the Gothic style were not unexpected. Like the programs in Hartford, Wallingford, and Providence, the axes of the building carry fully saturated windows. The west window truly dominates the interior, showing the Transfiguration flanked by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Again, the Overbeck models appear for the Apostles. The medieval English design of the Shield of Faith

Friedrich Overbeck,

Luke, print by Franz Keller,

distributed through the

Dusseldorf Union for the

Promotion of Good

Religious Pictures. After

Religiöse Graphik aus der

Zeit des Kölner Dombaus

1842-1880 [exh. cat.,

Diocesan Museum]

(Cologne, 1980).jpg)

Henry Sharp Studio, West

window, detail, Luke and John and

grisaille, 1871-72, Trinity Cathedral,

Episcopal, Pittsburgh. Photo: author occupies the rose. The writing on the bands is in Latin, with non est (is not) separating the members of the Trinity as separate persons, but connecting them to the central medallion Deus (God) by the words est (is). Given the size of the west window, Sharp placed two large panels of grisaille between the figures as well as providing a light blue background to the central Transfiguration. Thus the density of color is balanced by white glass, in general a skillfully mastered goal for all of the studio’s work.

Different painters? Different sources?

At Trinity we encounter different painting styles that are familiar from the First Unitarian Church of Providence. The face of the Angel Gabriel of the Annunciation is reminiscent of the face of Christ from the

Henry Sharp Studio,

Angel of Annunciation, detail,

1871-72, Trinity Cathedral,

Episcopal, Pittsburgh.

Photo: author panel of Christ among the Children.18 Most noticeable may be the heavy lidded eyes, where the pupils peak out as half circles. The painting is not in

Henry Sharp Studio, Christ,

detail from panel of Christ

among the Children, 1871-72,

lower windows, north

transept, Trinity Cathedral,

Episcopal, Pittsburgh.

Photo: author enamel, apparently; certainly the rest of the window is pot-metal glass with applied neutral vitreous paint on the surface, the standard technique for creating leaded and painted windows. The style, however, is markedly different from the Apostles, or the head of Christ in the lower transept window showing Christ’s relationship to humanity (accepting Baptism, speaking to the children, and exhorting Christians to loveone another). Christ’s hair is much simpler, detailed with uniform lines of trace, and his face more chiseled, especially the almost rectangular bridge of the nose. How was this process of variety within uniformity achieved? What relationship do the Providence and Pittsburgh commissions have especially in the integration of this possible English hand into a busy workshop?

Recent literature on medieval and Renaissance workshops, paints a picture of a dynamic group of individuals, often with markedly distinct “hands” within a shop. Far from the concept of a dominating “master” and obedient assistant, the belief is that creative artists associated in a synergy of production from design, to cartoon, to painting. A series of windows, now in the Detroit Institute of Arts dating around 1510-1525, are arguably by the same designer. The tall, elegant figures show the same figural proportions and fall of drapery, but their execution show two distinct hands, one favoring broad washes, the other hatch and cross hatch to define volume.19 Similar diversity within cooperative systems has been noted elsewhere. Once described as the circle of Peter Hemmel, the explosion of stained glass production around Strasbourg in the second half of the 15th century is now ascribed to a Strasbourg Workshop Collaborative. Sketches, cartoons, pattern books and workshop drawings were communicated in ways that that allowed iconographic expansion or contraction, repositioning of compositions, and alterations of scale. Breathtakingly impressive work resulted. 20

John and George Gibson of Philadelphia

The careers of two additional immigrants, John and George Gibson of Philadelphia reveal similar developments.21 Born in Edinburgh, the brothers were sons of a decorative painter. They trained both in Edinburg and England. William Gibson, an older brother, was a glass painter who had set up a studio in New York City in 1833; John joined him by 1837.22 John’s work was primarily decorative painting, not glass when he set up independently in Philadelphia in 1838. His expansion into windows began in the late 1840s. In 1849 he entered the Manufactures Exhibition of Philadelphia with a floral piece executed in enamel paints, produced with his brother William, which received a Second Premium award. Like many artists in glass, he had integrated into a community of fellow practitioners of the building trades, in 1840 marrying the sister of John Notman, a fellow Scotsman, who later became one of the most successful architects of Philadelphia. Notman’s buildings often feature Gibson’s work. George Gibson, the younger brother, after working in New York and England, in 1856 joined John to form J. & G. H. Gibson: A Glass Staining & Decorative Establishment.

John and George Gibson, East Grand

Stair of the Senate wing, 1856-61,

United States Capitol, Washington DC.

Photo: www.visitthecapitol.gov Different styles for the United States Capitol and for Ecclesiologist churches

Jean Farnsworth has profiled the firm’s accomplishments, chief among them the East and West Wings of the United States Capitol Extension from 1856 through 1861. The Engineer-in-Charge, Captain Montgomery C. Meigs had first approached Henry Sharp, but turned to the Gibson brothers when Sharp’s estimate turned out too high. The glazing was extensive, doors, windows and especially skylights, such as that gracing the East Grand Stair of the Senate wing. The style of decoration complements the classical inspiration of the interior with its Corinthian columns, marble, inlay, and gold trim. Like the surrounding ceiling, the window is divided into geometric segments, each richly worked with dense floral patterns predominantly in blue and gold on uncolored glass. Three circular

Capronnier Studio, Adoration

of Magi, detail Magi, 1862,

Howden Minster, Yorkshire, England.

Photo: author bosses anchor the middle section, each with realistically executed flowers and fruits painted in enamel colors. Eight smaller medallions of fruits and flowers appear at the sides. The painting is a marvel for its representational skill, similar to the popular still lives by James Peale or other artists of the second quarter of the 19th century. Remarkable well applied, the enamel shows almost no degradation after more than a century and a half. Farnsworth suggests that George H. Gibson may have learned techniques for porcelain painting from the Derby porcelain factory when he trained in England.

Enamel painting, however, was not a technique favored in commissions influenced by the Ecclesiologist movement, as discussed earlier. Flexible and astute, the Gibsons worked with their clients. Windows installed in 1869 at the Episcopal Church of St. Mark and St John, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania are similar to the work we have seen by Sharp, grisaille lancets with densely colored medallions linked by red and blue bands. The medallions carry symbols, such as the anchor of faith, the open book, and the Pelican in it Piety as well as inscriptions. The studio later also employed foreign-trained craftspersons. In the 1870s the Establishment’s memorial window department was headed by Henry Goetinck, who had been part of at the hugely successful Belgian studio of Jean-Baptiste Capronnier. Capronnier’s studio was also capable of producing windows in a variety of stylistic modes.

Samuel West,

Commerce, 1876, City

Hall, Holyoke,

Massachusetts,

Photo: John Suchocki.

The head and the sky

framing the figure from

the elbows up have

been restored.Samuel West

The Boston studio of Samuel West reflected a more conservative approach in American glazing.24 West was active in Boston from the 1850s to his death in 1891. 24 Like the Bolton brothers, West had been born in England but came to America as a child. His artistic inspiration, typical of most glass painters in New England, was the English experience of the revival of the

Samuel

West, Music, 1876,

City Hall Holyoke,

Massachusetts,

Photo: authorcraft.25 Originally associated with studios listed as "glass cutters," he published a thirty seven page catalog, A Glass Cutter's Guide in 1860. The catalog shows flocked or embossed designs similar to the Renaissance floral and architectural patterns displayed in Rice's Tremont House dome. The designs are more regularized, however, and applicable to ground or etched plate glass, typical of much of the glass found in entrance ways or transom lights. In 1870 he revised the guide, publishing it under the title The Glass Cutter's Assistant, which included the promotional entry that in its previous Fair, the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, has placed West "at the head of its list in stained glass."26 These forms were also popularized by early English publications such as Charles Winston's influential Hints on Glass Painting of 1847.27 Winston's illustrations included several examples of quarry designs such as the windows of Westwell Church, Kent, or Merton College, Oxford.

City Halls in Central Massachusetts and a Newport Church

Samuel West did considerable work in the New England area, notably the non-figural glazing of Trinity Church in Boston of 1876, in alliance with John La Farge.28 Previously, in 1871 West had been paid for windows of the City Hall, Chicopee, Massachusetts where both grisaille and figural glass intermingle. The fee of $1,958.96

Samuel West, Good

Shepherd and Angel of

Harvest, 1881-1882,

Channing Memorial Church,

Newport, Rhode Island,

Photo: authorindicates an extensive installation. The City Hall of Holyoke, Massachusetts received thirteen windows in 1876. The program included female personifications of agriculture, waterpower, commerce, industry, music, and art. Each of the figures is framed by a stylized floral border, and is set above a large circular motif intersected by a concave square with radiating petals. The portions of the women are Rubenesque; indeed the inspiration is indebted to 17th and 18th century models, even to the extensive three-dimensional sculpting of the figures.

West’s figures for the Channing Memorial Church, Newport, Rhode Island

Samuel West, Good

Sheperd, detail, 1881-1882,

Channing Memorial Church,

Newport, Rhode Island,

Photo: authorbetween 1881 and 1882 indicates the studio’s flexibility. 29 They are far more linear and flat. The figures stand on a grassy ground in front of a decorative dado. The unpainted blue glass in back of their heads is broken up into horizontal strips. There is a minimum of modeling, just a delicate stipple shading to support the contour lines. When faced with such fascinating work – each so different, yet competently executed, one wonders about the make-up of these early studios as well as the relationship between artist and patron. Did West have more than one designer in the studio – or was there a shift of employees between the two commissions? Rather, did West, or his patron, select a stylistic model deemed appropriate for each commission, and work in different modes responding to the context? In our Post-Modern contemporary world, we have become far more sensitive to differing artistic styles, even by the same artist, as well as collaboration across media. It is fervently to be hoped that we apply our new inclusivity to these kinds of works.

A rich field of early stained glass

One finds similar expression from this period nationwide. Early windows in major cities have often been lost to renovations while rural areas can reveal unexpected treasures. In St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Batesville, Arkansas, the chancel window is a three-part design very likely installed in 1870 when

Unidentified American

Studio, St. Paul and

symbols probably 1870,

chancel, St. Paul's

Episcopal Church,

Batesville, Arkansas.

Photo: courtesy of

Daniel Faggthe original wooden church was built. 30 The central lancet contains a standing three-dimensional figure of St. Paul against a blue background. Medallions above and below contain a glowing cross and an open Bible. The side lights comprise grisaille decorative systems containing flashed and acid etched medallions depicting Christian symbols such as the Lamb of God and the baptismal font. The grisaille patterns are similar to the examples published by Cox and Sons in their catalog of 1870 as well as the Sharp’s work.

A contemporary opinion concerning the originality of designs for such programs is revealed by the architect, Edward Tuckerman Potter who had designed the Church of the Good Shepherd, discussed above. His Gothic Revival edifice of Christ Church, Episcopal, in Reading, Pennsylvania contains windows dating from before 1866.31 Potter's description of the windows mentions four figural inserts in the central lancets of the windows in each transept, entrance, and chancel amid "stained glass arranged in geometric patterns enriched with symbols, medallions and figures."32 When considering the inclusion of figures in windows, he stated that one can have new figures designed or borrow from suitable sources. "The former course is so costly where artists at all equal to the work are employed as to make it in most cases as in this one quite out of the question." He explained that the south transept image of the Nativity was taken mainly from a picture by the Hon. Mrs. Doyle, A.R.A, the Crucifixion (called "The Dead Christ") in the north transept after Albrecht Durer [sic], and, in the chancel, the Ascension after Raphael [more likely the Transfiguration] above the Four Evangelists after designs of Overbeck (as discussed above in Sharp commissions).33

It is important, then, to realize that a long American experience of glazing was in place when, after the War between the States, a resurgence in building construction opened a more lucrative market for stained glass. American patrons began to purchase from Europe and European designers immigrated to the United States, challenging but also inspiring local studios. Subsequent chapters will treat the consequent development of opalescent glass and the influence of continental studios. Immigrant English designers continued artistic traditions traditional to the American studio, although they infused them with a renewed artistic vigor.

=

The Aesthetic Movement

Christopher Dresser, two designs

from Principles of Decorative Design

(1873), p. 156

The Aesthetic Movement, evident in America during the 1870s and 1880s, continued this productive relationship with England. As for the Gothic Revival, publications were influential in disseminating these new ideas to potential clients; American designers were quick to adapt. The publications by Christopher Dresser, particularly Principles of Decorative Design of 1873, influenced the stained glass of Aesthetic Movement design.34 Dresser's chapter on glass painting stressed the two-dimensional pattern of the window. He stipulated that even when working from nature, the artist should redesign the image so that naturalistic elements of shading and perspective would be eliminated. Dresser was a Lecturer on Botany and Botanical Drawing in the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria & Albert Museum), and the principles he brought to design can best be seen in the subtitle of his 1859 publication Unity in Variety: "As deducted from the vegetable kingdom; being an attempt at developing that oneness which is discoverable in the habits, mode of growth and principles of construction of all plants."35 The illustrations in Dresser's many texts developed hundreds of motifs abstracted from plant forms, easily carried over into stained glass, as well as wall paper, wall stencil pattern, or tile.

Aesthetic style windows

and screen, Cox & Son, 28 & 29

Southampton Street, London,

catalog of 1870 and 1872 American-based studios

Major artists and studios set up subsidiaries and some even transferred their location to the United States. Daniel Cottier set up a branch of his London studio in New York, and Charles Booth, originally from Liverpool, transferred to New York.36 Building on Dresser's work, Booth issued a pamphlet advertising this style when he arrived in this country. In 1877 he published Modern Surface Ornament and in 1878, the Art Worker,

Screen by William Gibson,

from Charles Cole, “Painted Glass

in Household Decoration,”

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine

(October 1879): 660where his designs as well as other English work, such as that Edward William Godwin were brought to American attention.37 English domestic uses of glass, as exemplified by the design for a fire screen published in the catalog of 1870 for the London firm of Cox & Son was quickly paralleled by American products. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published a screen by William Gibson, the New York glass stainer mentioned earlier. Its side panels show a meandering stem of flowers sprouting from a vase, the center presents a scene of domestic values, the “Lost Piece of Silver” (Luke 18:8). In an Egyptian setting, a woman happily shares her discovery of her lost coin after diligent sweeping. Framing the image are quarries set with Aesthetic style motifs.

Jefferson Market Courthouse

Charles Booth, attributed, Stained

glass window, about 1878,

Jefferson Market Courthouse,

New York. Photo:

ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com Such designs permit attribution to Booth of windows in the Jefferson Market Courthouse.38 The windows display pot-metal glass, predominantly light tints of blue, olive, gold and mauve, and white glass most commonly treated with silver stain in a variety of yellow shades. The trace paint is most often applied via stencil. The design of the window is structured around the vertical lancet divided into segments of differing ornament. Most significant is the use of flattened and stylized floral motifs set

Charles Booth, attributed, Stained

glass window with female heads, about 1878,

Jefferson Market Courthouse, New York.

Photo: ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.comagainst delicate geometric bands. Busts or other figural themes set within medallions of clear glass are also part of the décor, similar to those in the Cox and Son’s catalog.

The style became quite widespread. An article in the Art Amateur of 1881 contains six line drawings of predominantly aesthetic style patterns for screens and door panels, very probably taken from trade catalogs.39 The author addresses the home owner, describing the suitability of glass for the doors of bookcases, drawing-rooms, fan lights, and vestibules, stressing the wide range of prices. These abstract patterns were used as well for religious edifices. Possibly by Booth, or another studio working 40 The red brick Gothic Revival building was dedicated in 1875 and the windows undoubted installed by that date or shortly afterwards. The program includes a huge expanse of glass in various combinations of ornament. The lancet heads are particularly rich, displaying abstract floral bouquets. Deeper colors appear in the tracery lights that surround a quatrefoil displaying Christian symbols such as the dove,

Unidentified American

studio, possibly Charles

Booth, window detail,

about 1875, First Baptist

Church, Poughkeepsie,

New York.

Photo: John Hupcey

lily, anchor, grapes, olive branch, and crown. Without such symbols or with a different set such as a state seal or the scales of justice, these types of windows could function equally well in private homes and public institutions.

Booth's decorative work continued a tradition. He did not bring anything radically new, simply a style more up to date. As discussed earlier, patterned non-figural

Unidentified

American studio,

possibly Charles

Booth, window,

about 1875, First

Baptist Church,

Poughkeepsie,

New York.

Photo: John Hupcey

Charles Booth, Original

Designs from The Art-Worker

(February 1881), plate 8 glass, then called mosaic work, remained the standard form of window design throughout the 19th century. It is found in the most prestigious commissions, for example the original transept glazing of 1876 in Harvard University's Memorial Hall. Designed and produced by the Boston firm of MacDonald and McPherson, the rich medallion design sets a quatrefoil pattern outlined in red and blue fillets over variegated grisaille grounds. Harvard's program will be discussed at greater length in the following chapter.

English Studios and America’s protestant elite

The interior of the First Universalist Church with its combination of American craftsmanship and its incorporation of and adjustments to the English studio's stained glass underscores an important issue in 19th-century aesthetics. The

Bell and Beckham, London,

Crucifixion, 1883-1893,

south aisle, American

Cathedral of the Holy

Trinity, 23 avenue

George V, Paris.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinreverence for the products of English stained glass studios was a determining factor in stained glass installation in the United States dating from the 1830s. For important American ecclesiastical commissions before the mid-1870s, the stained glass of choice was the English import. The assumption that imported stained glass was superior to anything that might be produced domestically is demonstrated by the commission by Americans abroad. English designers were engaged at the prestigious setting of the American Cathedral of the Trinity in Paris, constructed 1882 through 1886. The parish serving American Episcopalians had been founded in the 1830s but the present church is associated with the appointment of John B. Morgan as rector in the 1870s. John was a cousin of J. Pierpont Morgan, the American financier and steel and railroad magnate who also shared a keen interest in the art and the Episcopalian religion. J.P. Morgan served as a senior warden of St. George’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan, colloquially referred to as "Morgan's Church". He also played a supportive role at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as trustee (1888–1904) and later as its president (1904–1913). Morgan’s collection of medieval illuminated books form the core the Morgan Library and Museum. When John B. Morgan began his

Bell and Beckham,

London, Ascension,

detail, 1883-1893,

south aisle, American

Cathedral of the Holy

Trinity, Paris. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin fundraising for a new worship space, he was reaching out to people already committed to arts in the service of religion and to the ability of contemporary expression to support eclectic revival styles. The cathedral was designed by George Edmund Street, the English architect of London’s Royal Courts of Justice of 1868, who most often worked in the Gothic style. The glass was designed by James Bell, active since 1865, who in 1883 collaborated with James Beckham to form Bell & Beckham.

The windows depict the familiar moments in the life of Christ and also theological juxtaposition of sacred figures arranged to illustrate the Te Deum Laudamus (to God Give Glory) text from the Book of Common Prayer. Installed between 1883 and 1893, all of the windows are consistent in format and execution. They follow a traditional, high Victorian format, a figural panel framed at top and bottom by abstracted architecture and stylized leaves. The draftsmanship of the figures is compelling, a crisp delineation of contours across angular facial planes and undulating folds of drapery. Three dimensionality is suggested but in a graphic system that evokes a print, rather than a painting.

In a signature church for Americans, both an English architect and stained glass studio were prioritized. Such a patronage bias was to reversed only with the advent of the Opalescent Era and the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge. The conflict, or competition, is particularly evident in the decade of the 1870s and it may be at its most legible in the city of Boston.

Henry Sharp Studio, Lamb

of God medallion within grisaille

lancet, 1863, St. Anna’s Chapel,

St Paul’s Episcopal Church,

Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Photo: author

Henry Sharp Studio, Lamb of God

medallion within grisaille lancet, 1859,

St. Peter’s Episcopal Church,

Oxford Mississippi. Photo: Michel M. Raguin

REFERENCES

![]()

1. ^ Sharp advertised in the New York City Directory in 1851 under the name Sharp and Steele, later as H. E. Sharp & Son, and H. E. Sharp, Son, & Colgate. Henry Sharp advertised in the south, especially after the War Between the States, for example in the New Orleans Morning Star, of February 26, 1868: "STAINED GLASS, HENRY E. SHARP, Nos. 147 and 149 EAST TWENTY-SECOND STREET, Between Third and Lexington Avenues, New York (information communicated by Jean Farnsworth). In addition to the commissions discussed in this essay, others can be noted. Sharp installed four windows in the transepts of the Church of the Holy Apostles, New York City, possibly during the late 1850s, damaged by fire in 1990. The windows’ design follows the pattern of the Renaissance roundels painted by Bolton in the previous decade. Sharp’s image of The Alms-Deeds of Dorcas is a copy of the engraving after W.C. T. Dobson published by Gebbie & Barrie. See Clark 1992, pp. 114-115, 133, also Edelblute, The History of the Church of the Holy Apostles (Privately printed, 1949), p. 58, and Jacob Landy, The Architecture of Minard Lafever (New York, 1970), pp. 149-150. The same kind of quarry glazing with pot-metal border remains in some of the windows of St. James Episcopal Church, New London, Connecticut, built by Upjohn in 1850. The New London church records were researched by the late Richard W. Becherer, Groton, Connecticut. St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Buffalo, architect Richard Upjohn, has Sharp windows (Upjohn 1936, fig. 55.). St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Rochester, New York has two double-lancet windows by Sharp that were originally on either side of a four light chancel window undoubtedly also by Sharp but now lost. These windows must have been installed when the chancel was enlarged in 1869. After renovations in 1897, the side windows were moved to the west ambulatory of the church. The Good Shepherd, similar to the Wallingford image, is linked to Christ and the Children; St. Paul and St. John show Overbeck Apostle designs. See Mrs. Elmer O. Cheney, "The Stained Glass Windows," in St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Rochester, New York,: A History of the First 150 Years (Rochester, 1977), 39-40, where the maker is listed as unknown, and an early sketch of the 1868 chancel, p. 14. I am grateful to Gwen (Mrs. Elmer O.) Cheney for providing the booklet and photographs of the windows. Sharp windows are noted in Christ Church (St. Peter Parish) Easton, Maryland (communication by Helene Weis), Grace Episcopal Church, Old Saybrook, and St. Patrick's Church, New Haven, Connecticut, windows presumably removed before the church was demolished in 1960. Information on the Connecticut commissions was communicated to the author by Gerald Farrell, Jr. The church of St. John's in St. Croix, Virgin Islands, has a window by Sharp and Steele, dated before 1866, heavily damaged in 1989, and now restored. Maureen Clarke "Hurricane Hugo versus St. John's" Stained Glass 86/4 (1991), 278-81. In 1859, the recently completed St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Oxford Mississippi installed Sharp’s glass in the chancel. See Jean Kiger, The Stained Glass Window of Old St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Oxford Mississippi (The Nautilus Publishing Company, Oxford MI, 2007).

2. ^ Research on Sharp, H. Hudson Holly, and the First Universalist commission was carried out by Jennifer Lee Cadero-Gillette, during the academic year 1989-90, communicated in Cadero-Gillette 1990. I am grateful for being able to reproduce much of Cadero-Gillette's research as well as significant portions of the text of her paper submitted in April, 1990 for a tutorial jointly sponsored by K. S. Champa, Brown University, and the author. In Wallingford, individual donors appear to have exerted considerable influence, resulting in a broader variety of designs and the presence of some enamel figural panels with quarry work in the side aisles. Later windows also appear in the side aisles of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral. The Church of the Good Shepherd replaced the nave side aisle glass with a figural series by Heaton Butler and Bayne, London, 1903/5. The London studio’s colors are restrained, so that considerable light enters the church, very probably an effort to retain the same effect as the grisaille of the original program.

3. ^ I thank Lance Kasparian for alerting me to this commission. Article in The Herald, Newburyport, Massachusetts on the Consecration of St. Anna's Chapel in St. Paul's Episcopal Church, (Tuesday, May 28, 1863), states "The most striking features are the memorial windows of richly stained glass, beautiful specimens of art designed and executed by Mr. Henry Sharp of New York."

4. ^ Harrison, 1980, pp. 82-83.

5. ^ The Colt Memorial window 1868, illustrated in Holly 1870, p. 270, carries inscriptions "and of our infant children Samuel Jarvis Colt, Elizabeth Jarvis Colt and Henrietta Seldon Colt," researched by Barbara McCroskery in 1978 and reconfirmed by Rick Marsaglia, 1991, while a student at Holy Cross College. I am grateful to the Rev. James A. Kowalski for facilitating my viewing of this impressive building.

6. ^ The Bowdoin chapel was built about 1846-1851 (Communication to the author, April 25, 1984 from Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Associate Curator, Department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Upjohn 1936, p. $$page.

7. ^ Ockwells Manor II, Bray, the Seat of Lt. Col. Sir Edward Barry Jr., Country Homes and Gardens Old and New (Jan. 19, 1924), figs. 1-6; Cox & Sons Catalog 1870, No. 148.

8. ^ I thank Gerald Farrell Jr. for his aid in obtaining information on this commission.

9. ^ The images were based on the charcoal drawings made by Overbeck between 1842 and 1853 for a fresco cycle in the chapel of the Villa Torlonia in Castel Gandolfo. They were reproduced in prints by Franz Keller and widely distributed, particularly through the Dusseldorf Union for the Promotion of Good Religious Pictures. See Religiöse Graphik aus der Zeit des Kölner Dombaus 1842-1880 [exh. cat., Diocesan Museum] (Cologne, 1980) ed. Walter Schulten, esp. pp. 12-15, Cat. Nos. 60 and 61, and Religiöse Graphik der Düsseldorfer Nazarener [exh. cat. Düsseldorfer Stadtwerke (Düsseldorf, 1982), ed Ludwig Gierse, Cat. Nos. 36-55.

10. ^ The identifications read from the left: Peter, Simon, Thaddeus, Andrew, James the Greater, Thomas, Christ, John, James the Less, Philip, Matthew, Bartholomew, and Paul.

11. ^ St. Anne’s relocated to the building of Lafever’s Trinity Church in 1969, after Trinity had stood vacant for a decade. The church was then renamed St. Anne and the Holy Trinity. Restoration of the window is described in Drew Anderson, Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, and Janis Mandrus, "Rediscovering Henry E. Sharp: The Conservation of the Faith and Hope Window at The Metropolitan Museum of Art," in The Art of Collaboration: Stained-Glass Conservation in the Twenty-First Century, ed. Mary B. Shepard, Lisa Pilosi, and Sebastian Strobl, Corpus Vitrearum USA, Occasional Papers II (Turnhout: Brepols) 2010.

12. ^ Although he provided detailed plans, Holly was not accepted as architect nor paid his requested fee. Cadero-Gillett (Cadero-Gillette 1990) discovered original drawings and letters including a letter from “Office of H. Hundson Holly, Architect, April 26, 1873: “I consider that the motive was wholly taken from my design”; note by church: “He made a Bill of $600, but it was settled March 17, 1874 for $250.”

13. ^ Holly 1871, p. 155. See also in Holly, Chapter IV, "against shams" dominated by Ruskinian sentiment of authenticity and the natural in building construction.

14. ^ Church archives; see above, note 12.

15. ^ See Sarah Brown for “The Age of Enamels” in Stained Glass: An Illustrated History (New York/Avenel, New Jersey: Crescent Books, 1992), pp. 113-126. Although a highly effective painter in glass, Peckitt was not a skilled draftsman and his best windows relied on drawings he commissioned from others. For a well-illustrated study of other enamel work of the time, see Geoffrey Lane, “'A Fine Window at Price's': Sanderson Miller, William Price the Younger and the Uses of Stained Glass in the Mid-Eighteenth Century,” The Journal of Stained Glass, vol. 36 (2012): 10-37.

16. ^ The reasons for the absence of textualized evidence can only be surmised. The studio very likely would not want to have its own work seen as subservient to that of its foreign competition. The circumstance of reuse of windows destined for another confessional group, such as the purported Lutherans, may have been awkward for the Unitarian congregation. Thus, neither Sharp nor the congregation would have perceived any advantage in including these circumstances in published records.

17. ^ See Jeanne Farnsworth, “An America Bias for Stained Glass,” Nineteenth Century, vol. 17, no. 2 (Fall 1997): 15-20. See further, John La Farge’s sentiments concerning the preference for English studios when he began his work at Trinity Church in Boston.

18. ^ Sadly, the window had not been protected during a painting project, and drops of paint have fallen in the glass.

19. ^ Virginia Raguin, Stained Glass before 1700 In Midwest Collections, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio [CorpusVitrearum United States Of America, VIII] (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2002), vol. 1, pp. 201-210.

20. ^ Harmut Scholz, “Monumental Stained Glass in Southern Germany in the Age of Dürer,” in Painting on Light, Barbara Butts and Lee Hendrix, eds., [exh. cat. The J. Paul Getty Museum] (Los Angeles, 2000), pp. 17-42. See also for studies of workshop practice in France, Michel Hérold, “La production normande du Maître de la Vie de saint Jean-Baptiste: Nouvelles recherches sur l’usage des documents graphiques dans l’atelier du peintre-verrier à la fin du moyen âge,” in Pierre, lumière, couleur,” Studies in honor of Anne Prache (Paris: Presses de l’Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1999), pp. 469-85.

21. ^ Jean Farnsworth, “John and George H. Gibson ‘really have the cream of the bus[iness] in their line’,” The Journal of Stained Glass, vol. 37 (2014): 22-48. This exhaustively researched article presents contemporary criticism, account statistics, and competitive bids among competing studios for an overview of the era. Unless otherwise noted, all information in this section comes from Farnsworth’s article.

22. ^ Catherine Hoover Voorsanger and John Howat, Art and the Empire City [exh cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art] (New York, 2000), pp. 350-351

23. ^ West installed grisaille windows in 1868 for the Town Hall of Easthampton. See Obituary in Boston Evening Transcript (April 27, 1891): 2, and Laurel A. Maziarz, Easthampton, Massachusetts, "Stained Glass Work of Samuel West," typescript, 1983, 1-23. Ms. Maziarz has researched the career of Samuel West and has generously shared her conclusions with the author.

24. ^ Samuel West's also provided windows for cathedral of St. Paul, Worcester, 1870s, now lost. Three figural scenes were set under canopies in each light of the triple lancet windows. On the left was the Resurrection flanked by Mary Magdalene Meeting Christ in the Garden, and the Three Marys at the Empty Tomb. On the right was the Nativity flanked by the Annunciation and the Assumption. At the base of each window were the traditional mosaic designs and stylized flower inscribed by a circle, diaper work, and architectural motifs, familiar from windows of the Holyoke City Hall. Maziarz 1983, pp. 1, 23-28. The chancel was renovated in 1952 and West's windows replaced by windows designed by Claire Leighton, fabricated by the John Terrence O'Duggan studio of Boston. Claire Leighton, The Windows of the Cathedral of St. Paul (Worcester, 1952).

25. ^ For one of the most comprehensive surveys of glass painting in the first half of the 19th century in England see Haward 1984 and Birkin Haward, Nineteenth-century Suffolk Stained Glass (Cambridge, 1989).

26. ^ Eleventh Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association [Faneuil and Quincy Halls, Boston] (Boston, 1869), 133, Entry No. 993. The judges commented that the class of "glass, earthen and stone ware" was not large. Regarding West's works "they will bear favorable comparison with any productions of foreign artists. Every endeavor to bring the work of our skillful American artists into successful competition with those of other lands deserves encouragement, and we therefore recommend an award to Mr. West of a Silver Medal."

27. ^ Winston 1847, especially pls. 1-6.

28. ^ Lance Kasparian has identified windows around 1870 in in Emmanuel Church, Boston attributed to West: Four Evangelists (Griswold Memorial) and Life of Christ (Rand, Lawrence, and others Memorial) Virginia Chieffo Raguin and Lance Kasparian, "Stained Glass Study in the Back Bay" Tour Notes: 50 Annual Meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians (March 31, 1990), 12.

29. ^ The Channing Centenary...with and Account of the Building and Consecration of the Channing Memorial Church (Boston, 1882), 546-9; the church was surveyed by the Census of Stained Glass Windows in America in 1989, by the Rhode Island survey team of Jane Hayward, Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, and Luly Duke. The church would later commission opalescent work by Donald MacDonald of W. J. McPherson & Co. of Boston and by John La Farge. I am grateful to the Rev. Frank W. Carpenter for making a copy of the The Channing Centenary available to me.

30. ^ In 1917 the window was transferred the present church building. I am grateful to communications from Daniel Fagg, Professor of History, Arkansas College, for information about this window.

31. ^ See pamphlet by Edward T. Potter, Esq. Architect, New York, Christ Church, Reading, PA, (Reading, PA, 1866). I am grateful to Frederick L. Walters of John Milner Associates, Inc., for providing a copy of the pamphlet as well as additional information about the church and its windows.

32. ^ Ibid., 4.

33. ^ The images, however, are fragmentary, for example, "The Dead Christ" presents only the body of Christ on the cross, and one is hard pressed to make the association with any of Dürer's works.

34. ^ Principles of Decorative Design (London, 1873) is illustrated with 183 designs in text. Studies in Design (London, 1876) is a large folio volume with 60 chromolithograph plates, and was, obviously, more expensive. For extensive bibliography see Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, in Pursuit of Beauty, pp. 421-23.

35. ^ Title page, Unity in Variety (London, 1859).

36. ^ See Cottier & Co.'s window for the New York Society Library in 1878: Cole 1879, pp. 662-63, ill.; "Cottier & Co., of Fifth Avenue and Pall Mall...introduced what is known as the English Domestic style of Stained Glass," Riordan 1881, p. 233. See also Harrison 1980, pp. 47-49.

37. ^ Charles Booth and others, Modern Surface Ornament (New York, 1877); Art Worker, A Journal of Design Devoted to Art-Industry I (January - December, 1878). The February issue, pl. 8, shows designs by Charles Booth, "Glass Stainer, 47 Layfaytte Pl., New York". For Godwin see Pursuit of Beauty, pp. 431-33.

38. ^ Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen in Pursuit of Beauty, pp. 180-84, ILL. 6.4.

39. ^ Mary Gay Humphreys, "Colored Glass for Home Decoration," Art Amateur 5/1 (1881) 14-15. Humphreys cites prices ranging from $1.50 to $100 a foot and mentions visiting "Lambs'", presumably the J. & R. Lamb studio of New York, advertising in the journal.

40. ^ I express my thanks to Sue Lumb and Fred Maddocks for their work in documenting stained glass in Poughkeepsie.