The centrality of traditions for a heterogeneous population.

Imported windows are documented early and continued to be popular throughout the history of American glazing practices. Even during the height of the opalescent era, when "American glass" was making inroads into European

markets, American patrons still commissioned significant numbers of windows from European studios.

Königlichen Glasmalereianstalt, Lamentation,

1846, south nave, Cathedral

of Cologne. Photo: author

The very nature of the window as a revival art supported these choices. Many revival styles were associated with particular ethnic or national traditions. Public art in a nation of pluralism ineluctably reflected these many diverse publics. The stylistic choices were conditioned by the nearness of a local studio, the patterns of commissions of diocesan organization, and, above

Louis Charles Steinheil, designer,

Eugène Oudinot Studio, fabricator,

St. Stephen before Judges, 1863,

Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin all, by the acquired sense of the "appropriate" of each congregation. Community remembrance of forms and images exercised the dominant evaluative role. In a climate of heterogeneous patronage, then, stylistic diversity and the absence of any chronological progression were absolutely normative. Despite the apparent distance in social class, the programs of the recent immigrants partook of precisely the same nostalgia for a past that suffused the most extravagant turn-of-the-century buildings by the Anglo-American economic elite. Commenting on the Newport homes of American millionaires, the French visitor Paul Burget wrote that the unconscious effort to bond with the past is what saved these homes "from being coarse." He was touched by "the sincerity, almost the pathos, of this love of Americans for surrounding themselves with things around which there is an idea of time and stability. ... It is almost a physical satisfaction of the eyes to meet here the faded colors of an ancient painting, the blurred stamp of an Antique coin, the softened shades of a tapestry of the Middle Ages. In this country, where everything is of yesterday, they hunger and thirst for the long ago. We must believe that the soul of man is possessed by an indestructible desire to be surrounded with things of the past, since these extravagances of luxury subserve such a desire."1

Windows were a part of an architectural setting, their program invariably determined by the patron, and their site-specific message articulated in form and symbol of collective tradition. Even granted the commercial and/or critical success of a La Farge or a Tiffany, the field of stained glass remained profoundly conservative in its aims. The window, of necessity, affirmed tradition, so that "art" in this medium often became not only eclectic, but unchanging. For example, almost seventy years separates Nazarene painting and the stained glass of the Tyrolese Art Glass Studios work in the United States. The young artist Johann Scheffer von Leonhardshoff painted the Death of St. Cecilia in

Johann Scheffer von Leonhardshoff, Death of

St. Cecilia, 1820/1, Vienna, Belvedere

Palace and Museum.

Franz Pernlochner designer,

Tiroler Glasmalerei Anstalt

(Tyrolese Art Glass Company)

fabricator, Story of Abraham 1886,

Cathedral of Saints Peter and

Paul, Providence Rhode Island.

Photo: author

1820/1 while living with the Nazarenes in Rome, and Franz Pernlochner designed the Story of Abraham for the Providence Cathedral, Rhode Island, in 1886.2 Both partake of the same generic styles and speak to an unchanging tradition of religious images very much admired by the congregation. Once studios became accepted by a locality, a class, or confession, there was a good chance that their work would continue to be imported. The stained glass of Henry Holiday, Clayton & Bell, or Cottier & Co., familiar from the glazing of Trinity Church, Boston in 1877, continued to be purchased by Americans. In competition for the increasingly diversified audience, however, were the Continental studios, which were predominantly French, German, and Austrian.

French influence in New York and beyond

Although the majority of imported glass in the early 19th-century is attributed to English sources, a condition tied to the hegemony of the Anglo-American population, continental imports also occurred. Louis Philippe, the France monarch, gave windows produced by the Sèvres studio to the archdiocese of New York probably around 1846.3 Louis Philippe was an active patron of the revival of stained glass, and the windows are typical examples of the Sèvres manufacture for their time. Six windows from this donation have been installed in Fordham University Chapel, Bronx, New York.4 Like the windows in the Royal Chapel at Dreux, the panels show single standing figures framed by canopies.

Sèvres studio, St. Paul, gift of

King Louis Philippe of France

about 1846, Fordham University

Chapel, Bronx, New York,

Photo: Rohlf’s Stained &

Leaded Glass Studio.

Although displaying some intense pot metal colors, the design depends primarily on the dexterous use of applied paint to neutral colors to achieve a highly three-

Antoine Lusson, fabricator, St. Radegund, 1854,

Sainte-Clotilde, Paris. Photo: author.

dimensional modeling. The commission of two French studios, Henry Ely of Nantes and Nicolas Lorin of Chartres to provide windows for New York's Cathedral, begun in 1858, is understandable given this French precedent.5 The long-lived Lorin Studio did work in multiple styles, but for St. Patrick, produced what was then a common mix of 19th-century adacemic figural tradition and Gothic-inspired decorative framing. James Renwick had designed the architecture in an eclectic mixture of High Gothic style inspired by precedents from France England, and Germany. Lorin’s windows convey the narrative through dramatic realistic detail, for example, the interacting conversation groups surrounding St. Patrick instructing the faithful or the busy clergy working with Reverend John M. Farley and Archbishop John Hughes to plan the New York cathedral. Like the glazing of the basilica of St. Clotilde in Paris, the three-dimensional modeling of the form is set against deeply saturated damascene backgrounds confined within Gothic architectural frames. Indeed the selection of French glass may have been encouraged by Archbishop Hughes’ visit to Paris in late 1861 through early 1862 at the behest

Nicolas Lorin, Founder’s Window, 1879,

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York, NY.

Photo: author.

The window was given by the

cathedral’s architect, James Renwick. He had

been named architect in 1853 but construction

of the great Gothic Revival building extended

from 1858 to 1879.of President Lincoln. Hughes’ mission was to prevent the recognition Confederate States by the government of Napoleon III.6 It is unthinkable that he would not have visited the recently completed St. Clotilde, the preeminent royal commission, and first fully Gothic-Revival edifice in the city.

The influence of Continental studios became quite important during the last quarter of the century, a phenomenon that kept pace with the growth and economic strength of Roman Catholic immigration.7 The studios offered an extremely reliable product. The continental glass came from huge workshops, sophisticated ovens, and well trained craftspersons. Enamel colors or traditional neutral paint were invariable fired under ideal conditions. The structural integrity of the window was insured by employment of standard sizes and types of glass segment, lead came, and support structure of iron frame and saddle bars. Also, the patron could rely on the window designers' complete familiarity with Roman Catholic pictorial traditions, such as depictions of the Sacraments, the Mysteries of the Rosary, or favorite saints of ethic popularity [See Appendices]. Depth of experience and reliability, and perhaps even the mystique of "brought to you from far away at great expense" served the European studios well. There were crossovers in patronage, such as the employment of Mayer of Munich by St. Paul's Episcopal Church in New Orleans, or Hardman and Co., Birmingham by St. Michael's Catholic church of Providence, Rhode Island.8 Frequently the studios produced in a different style for such patrons, as evident in the Tiroler Glasmalerei's description of windows "fully in the English style" made in 1892 for an Episcopal Church in Pelhamville, New York.9 The general pattern, however, gave great weight to ethnic patronage and language identity.

Notre Dame, Indiana and Carmel du Mans (later known as Hucher Studios)

Basilica of the Sacred Heart,

interior nave, 1981-1874, University of

Notre Dame, Indiana. Photo: authorFrench missionaries, coming down the Mississippi from Canada had early

Lorin Studio, Chartres,

Portrait of Rev. Edward Sorin,

C.S.C. ,1880, Basilica of the

Sacred Heart, Notre Dame,

Indiana. Photo: author arrived in the Mid-west. In 1687 two Jesuit explorer/missionaries, Jacques Marquette and Claude Allouez, founded the Saint Joseph’s Mission near present-day Niles, Michigan. With the suppression of the Society of Jesus by the papacy in 1773, the mission was abandoned. (The Jesuits were reinstated by Pius VII in 1814.) In the early 19th century new efforts were made to support the indigenous population. In 1842 Father Edward Sorin, C.S.C. (Congregation of Holy Cross) began both a school and a parish in the mission that was known as Notre Dame du Lac. A meticulously executed portrait painted in 1880 as a window by the Lorin studio of Chartres, shows the revered founder with the dream of his college below.

The University of Notre Dame prides itself as the oldest, continuous parish founded and staffed by the Congregation of Holy Cross. After the initial log cabin structure, a larger church was erected in 1848. The present edifice dedicated to the Sacred Heart and built between 1871 and 1875 replaced it. The Congregation of the Holy Cross takes its name from neighborhood of Sainte Croix in Le Mans, where the Rev. Basil Anthony Moreau founded the community in

Studio of Carmel du Mans, Window of

St. Helen and St. Elizabeth, 1875, Signature,

Carmel du Mans, F. Rathouis, 1875;

the True Cross Resuscitates the Dead and the

Visitation, Basilica of the Sacred Heart,

Notre Dame, Indiana. Photo: autho1837. It is thus not surprising that the order engaged a French studio

initially owned by the Carmelite monastery in Le Mans to provide windows for the new church.10a The studio of Carmel du Mans thrived between 1853 and 1903; often the succeeding directors included their names in the signature of the workshop. E10c Thus we find “Carmel du Mans, F. Rathouis 1875” in the lower border window of St. Helen, mother of Constantine and the discoverer of the relic of the Holy Cross, and St.

Studio of Carmel du

Mans, Procession of the Relics of

St. Martin of Tours, 1875,

Basilica of the Sacred Heart,

Notre Dame, Indiana.

Photo: author Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist. The installation of windows apparently continued after 1875, as the signatures later testify to the director ship of Eugène Hucher (died 1889) and his son Ferdinand Hucher (died 1903).

The subjects of the windows are site specific, stressing the French tradition in the New World and well as Catholic doctrines. They are integrated within the larger program of statuary and wall painting within the impressive Gothic structure. Subjects include saints cherished in French devotion, such as St. Radegonde, the Merovingian queen who founded the monastery of the Holy Cross in Poitiers, St. Martin of Tours, who emerged as a model of charity after he cut off half of his mantle to give to a freezing beggar, Saint Louis, the 13th- century king of France who received the relic of the Crown of Thorns and subsequently enshrined it by building Paris’ Sainte-Chapelle, Christ showing his Sacred Heart to blessed

Studio of Carmel du Mans,

Window of St. Louis and St. Dominic, 1875:

Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Notre Dame,

Indiana. Photo: authorMary Margaret Alacoque, a 17th-century French nun, and St. John Eudes, the 17th century French priest who encouraged devotion to the Sacred Heart of Mary. The honor given to the Sacred Heart of Mary and Sacred Heart of Jesus is symbolically portrayed by a young woman keeling with a model of the basilica of the Sacred Heart in Paris. The Virgin presents the woman to Christ. A banderol carried by an angel reads in Latin: the French people are devoted to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Construction had only just begun on the basilica in 1875, so that the image in the window of the finished edifice was arguably prospective, based on published plans. Thus, Notre-Dame’s windows attest to the keen interest

Studio of Carmel du Mans,

Dedication of France to the

Sacred Heart, 1880?,

Basilica of the Sacred Heart,

Notre Dame, Indiana.

Photo: author of the Order in keeping vital contact with the country of its origins.

New Orleans’ French heritage

New Orleans presents a fascinating study as verified by research by Jean Farnsworth on early glazing practices.10b Before the War between the States, foreign imports do not appear to have been common. The earliest reference to glazing may be windows installed in 1841, simply called "glazing of color" for St. Augustine's Catholic church, serving a French speaking population.11 Like Boston in the 1870s, New Orleans witnessed a spate of church construction and embellishment after the war. Where the Anglo-American population of Boston turned to English studios, the French heritage of New Orleans drew it to French producers.12 In a pattern common to church construction for Catholic congregations, many buildings were finished and provided with temporary glass, awaiting the financial capabilities for the next generation. The Church of the Holy Trinity, for example, had been constructed in 1852/3 for a German-Catholic parish, but by an architect of French heritage, T. E. Giraud. The building was renovated in 1873, the presumed date of the installation of twelve double and four single lancet windows by Charles des Granges of Clermont-Ferrand, France.13Des Granges set three-dimensional figures against flat damascene patterned backgrounds. The figures, however, spill out over the thin columns that border the narrow fictive niches. The rounded window openings may have determined the choice of Romanesque-inspired architectural patterns. In bright shades of blue, gold, and red, the upper portion of the window describes sculpted moldings in the overturned leaf and fret design similar to those of 12th-century embrasured doorways. The profusion of colors, patterns, and spatial planes, however, is clearly the product of a 19th-century eclectic mentality.

The early Protestant churches in Louisiana, however, were more prone to employ London-based firms. The first figural glazing in New Orleans was presumably windows produced by William Gibson of New York in 1855 for Trinity Church, Episcopal. The three-light window was located above the altar. In 1874, Gibson's work was removed and replaced with an imported English commission. The Crucifixion window was designed by Nathaniel Hubert John Westlake, then chief designer for the firm of Lavers, Barraud & Westlake.14 Westlake was keenly aware of archaeological precedent, for he is best remembered to scholars as the author of a seminal work, A History of Design in Painted Glass.15

Immaculate Conception in New Orleans, work of the Hucher Studio of Le Mans

The Jesuits called upon the firm directed by Eugène Hucher of Le Mans about the same time that the Congregation of Holy Cross made its contact for Notre-Dame. Indeed the enterprise was one of the major studios of France during the 19th century. 16 In 1857 a new church

Church of the Immaculate Conception, façade,

130 Baronne Street, New Orleans. 1857,

reconstructed 1930.

building dedicated to the Immaculate Conception 130 Baronne Street, was open and embellished over time.17 Its interior retains a brilliance of color, forms, and sheen. In 1873 the priests installed a marble altar imported from Lyons and they purchased a marble statue of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception that reputedly has been commissioned by Marie Amélie, wife of king Louis Philippe.18 The setting for the statue above the high altar was patterned after a similar shrine in the Jesuit foundation in Pau, France. The glazing by Hucher [See Appendix] took place between 1878 and 1880.19

Church of the Immaculate Conception, interior

looking toward chancel, New Orleans. 1857,

reconstructed 1930. Photo: Michel M.

Raguin

The Continental studios supported a considerable amount of exchange between nationalities, despite the often chauvinistic claims of national superiority in the press and studio advertisements. In 1855, two years after Hucher had become the artistic and archaeological advisor for the studio, then associated with the Carmelite Convent of Le Mans, he hired as designers Karl and Friedrich Kückelbecher, artists trained in the Munich Nazarene tradition. The limpid beauty of the Nazarene style, with its clarity of its color and sentimental figural grouping, infuses the chancel windows dedicated to Mary.20 The aisle windows of the history of the Society of Jesus are evidently by a different designer more grounded in contemporary academic illustrative art.21 The church building is in a Moorish design and the elaborate architectural frames surrounding the windows incorporate Moorish motifs. The stylistic choice is credited to the influence of Fr. John Cambiaso, the first rector of the Jesuit community who had previous held teaching positions in France, Sardinia, Africa, and Spain.22 Islamic-inspired tile patterns appear both above and below the highly three-dimensional scenes of Jesuits engaged in their mission in all four corners of the globe. An undulating eastern arch design frames both the large scene and the arcade above, where, in a central niche an angel holds a shield with the monogram of the name of Jesus, IHS. The scenes include events from the lives of Jesuits saints such as Peter Claver ministering to slaves in Cartegena, Columbia, and the beheading of John de Brito at Oriur, India, each with specific localizing details.

Hucher Studio, Le Mans, The Beheading

of John de Brito at Oriur, India, 1878-1880,

north nave aisle, Church of the Immaculate

Conception, New Orleans. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

Hucher Studio, Le Mans, Peter Claver

Ministering to Slaves in Cartegena, Columbia,

1878-1880, nave aisle, Church of the

Immaculate Conception,New Orleans.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin The images are highly pictorial with realistic recession in space, Renaissance-style figures, and dramatic compositions.

Transitions across patronage

The interchangeability of the continental firms, as exemplified by the employment of Nazarene-style designers by Hucher, also characterized the American Catholic experience of patronage. Shortly after the burst of patronage of French studios by New Orleans institutions, the trend shifted to acquisitions of windows from German studios. An installation in Florida demonstrated how similar German-produced work seemed to all "continental" work to the Catholic patron. A program incorporating the same iconographic and stylistic characteristics as Hucher's work for the Church of the Immaculate Conception was installed in 1900 in Tampa. The F. X. Zettler studio of Munich produced these windows for the Church of the Sacred Heart , staffed by members of the Society of Jesus.23 Similar to the installation in New Orleans, the chancel windows are the most tied to general Catholic doctrine and beliefs. Flanked by the Annunciation and the Nativity, the central window presents Christ revealing his Sacred Heart, a devotion particularly dear to the Jesuits. [See Appendix: Immaculate Conception Church]. At the sides of the church are windows of saints.

Not only the general subject matter but also details within each representation show doctrinal sensitivity. The central role of the missionary work and devotion to the Eucharist in Jesuit tradition is clear. Christ reveals his glowing heart and immediately behind him is a depiction of a radiant monstrance holding the consecrated host. In another window, St. Barbara is shown accompanied by angels who bring Holy Communion to St. Stanislaus Kostka and Ignatius and his followers are seen receiving communion. Not only is St. Louis depicted defending the faith as a Crusader in the Holy Land, but St. Patrick is shown preaching at Tara. The Jesuits were founded as teachers, missionaries, and preachers. The iconography is wholly consistent, articulate, and site-specific. Even the inclusion of rounded arches and turret-like structures in the architectural frame for the images repeats the exterior massing of Romanesque forms of the building itself. The Society of Jesus clearly had achieved a responsive relationship with its studio.

Cathedral of St. Francis, Santa Fe, New Mexico

.jpg)

Cathedral of St. Francis, Santa Fe, New Mexico,

1869-1886, south nave, seen from transept.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Ethnic heritage and familiarity also conditioned the selection of

Félix Gaudin, Clermont-Ferrand, France,

St. Andrew, 1886, Cathedral of St. Francis,

Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin architectural and the glazing styles of the Cathedral of St. Francis of Assisi, Santa Fe, New Mexico, built between 1869 and 1886. The building was designed after a French Romanesque model and the windows purchased from a French firm, decisions undoubtedly reflecting the appointment of the French-born John B. Lamy as first archbishop of Santa Fe.24 The inscriptions are in Latin, at that time often considered by the clergy a means of stressing the universality of the church and playing down ethnic separatism, particularly important given the ethnic differences between the clergy and the predominantly Hispanic populace. Throughout Lamy’s tenure considerable tensions marked a European – and centrist movement, especially with Pope Pius IX whose long term in office marked and increasing consolidation of power in Rome and the papacy. Even the names of the donors are integrated into the Latin text. Under the image of St. Andrew, for example, one reads SANCTE ANDREA O.P.N. (ora pro nobis) SACRATISSIMI CORDIS JESU SODALITAS DEDIT: St. Andrew, pray for us: Given by the sodality of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The dedication reflects the prevalence of church associations that united the laity in edification and in good works.

The vibrant colors and bold design are admirably suited to the intense light experienced in the location of Santa Fe. The windows of St. Paul and St. Peter were originally in the chancel area and both are signed at the bottom FELIX GAUDIN/ PIXIT CLERMONT/ FRANCE: Painted by Félix Gaudin, of Clermont-Ferrand, France. The Gaudin firm, still operating today, was extremely prolific in 19th-century France.25.jpg)

Félix Gaudin, Clermont-Ferrand, France,

signature below St. Peter, 1886, Cathedral of

St. Francis, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

Germanic influence: Munich windows in Buffalo, 1855

Catholics from German-speaking areas of Europe- Austria, Bavaria, and the Rhineland were more prone to patronized Munich and Austrian manufacturers. During the first half of the 19th century Munich was viewed as the premier example of the revival of liturgical arts under an inspired monarch. One of the earliest examples of Bavarian presence in America, however, appears to have been the result of an ethnic Irish bishop of Buffalo visiting Europe and making a personal selection. This was a time-honored pattern of decision making in the architectural arts. Twenty years later, Phillips Brooks would visit the London studio of Clayton and Bell to select windows for the chancel of Trinity Church, Boston, discussed earlier. Buffalo's cathedral was designed by Patrick C. Keely, the architect who would produce huge numbers of Catholic churches in the North East. The construction of the Gothic Revival building began in 1851 and the dedication took place in 1855.26 The first Bishop of the "frontier" diocese of Buffalo, John Timon,

Josef Scherer, Munich, Nativity, Crucifixion,

and Resurrection, 1854, Cathedral of Buffalo,

New York. Photograph: Michel M. Raguin engaged Keely and also visited King Ludwig of Bavaria in 1854/5.27 He acquired

Patrick C. Keely, Cathedral of Buffalo, New York,

interior, looking towards chancel, 1851-1855.

Photo: author from the then deposed king the three sanctuary windows of the Nativity, Crucifixion, and Resurrection (see detail). The commissioning of the windows was associated with the King’s Ludwigs-Missionsverein (St. Louis missionary society) founded in 1838 to support Catholic efforts in Asia and North America. It also provided Buffalo’s cathedral with several oil paintings, some by Johann von Schraudolph and his disciples, as well as other church furnishings. Bishop Timon October 1855 wrote a letter to the Missionsverein thanking the king for money to pay for the windows.

The windows were the work of Josef Scherer, a highly accomplished and prolific designer of glass who began his studies in in Munich in 1832. Closely allied with the artistic philosophy of Boisserée brothers, Josef collaborated with his brothers Alois, Leo, and Sebastian, The Schere brothers were centered in Stuttgart between 1845 and 1852 and produced windows for the Frauenkirche and St. Peter's in Munich, as well as churches in Stuttgart and Landshut. They then moved to Munch where the commission for Buffalo was executed.28 Visually the windows are extremely close in style to the "Bavarians" of the south aisle of Cologne Cathedral, executed between 1844 and 1848, also by the Königlichen Glasmalereianstalt.29 The windows in Buffalo show the same organization of a single dominant figural scene across all lancet subdivisions. The same color harmonies of ochre, royal blue, lavender, emerald green, and burgundy dominate the image and are set against the white and gold architectural surround. The figural types are absolutely identical. Raphaelesque-inspired figures of nobility and sweetness operate in a dignified tableau. The large groups of actors create the three dimensional space framed by the Gothic architectural forms. At the upper portions of the window lacy spires occupy the termination of the trefoil lancets.

The Archdiocese of Hartford, Connecticut and the Tyrolese Art Glass Company

Documentation of activity by these German and Austrian glass painters can be found in lists of commissions kept by many of the studios still extant. The lists, however, cite American commissions only in the 1880s and the self-documentation by studios are notoriously incomplete. Publication by the studios themselves, such as the 1894 volume commemorating the forty years of business by the Tiroler Glasmalerei can be very helpful, especially in revealing the studios' own ideas of what appeared to be its flagship commissions.30 A special section was devoted to windows installed in the United States, and one of the firm's largest commissions was the cathedral of Hartford, built by Keely, now lost to fire. The Hartford window of Christ Calming the Sea, installed in 1888, was illustrated.31 The tremendous success of the German studios at this time also indicates astute business practices. Most of the studios set up an American business office. The Tiroler Glasmalerei was known as the Tyrolese Art Glass Company at 50-61 Park Place, New York. Mayer signed the studio's windows in America as "Mayer and Co., Munich, New York," and F. X. Zettler also had an American branch. Even before World War I, which would obviously impact business, a studio often worked through an American firm who acted as its agent. In 1910, the Daprato Statuary Company of Chicago and New York advertised itself as the sole representatives for Zettler in the United States and Canada.32

Tyrolese Art Glass Company, Innsbruck, Austria,

Order Books, St. Francis of Assisi,

Sacramento, California

Photo: author

Some studios have preserved records, and the order books of the Tyrolese Art Glass Company reveal the process of commissions prepared half-a globe away. With the development of America’s western states in the early years of the 20th-century, churches in California became good clients. The Franciscan-founded church of St. Francis of Assisi in Sacramento was dedicated in 1910, resplendent with windows manufactured in Innsbruck. Of the cost of the building, $100,499, its 46 windows amounted to $9,950, or about a tenth of the total. The records of the Studio confirm those preserved by the church. The TGA’s order books are vividly detailed: measurements of the openings that will received the windows, information about the site, pastor’s and architect’s directions, list of the subject matter, and frequently photographs.

The Northeast Irish

By the 1860s the Irish immigrants in North East had developed a sufficient concentration to begin large scale church buildings.33 Documentary evidence is extremely scarce so that inference drawn from style must be used to develop a history of these early relationships. Typically the first windows commissioned were near the altar; the rest awaited the availability of funds. It appears likely that the three chancel windows of St. John's Church in Bangor, Maine, built

American Studio, possibly Henry Sharp, Virgin,

Christ, and John the Evangelist, chancel

windows, St. John's Church, Bangor, Maine,

built in 1855/6. Photo: Michel M. Raguin in 1855/6 came from an American studio.34 The brilliant purple, red, blue and green harmonies and the damascene pattern blending figure and frame are not unlike the windows produced by the Henry Sharp around this time. St. Francis de Sales in Charlestown, Massachusetts, shows chancel window of a similar composition that probably date close to the dedication of the church in 1865. The windows show a three-dimensional Renaissance-inspired figural style, dense diaper patterns in the background, and brilliant contrasts of primary colors. Both buildings, however, turned to Munich or Austrian studios for their full complement of windows later in the century. St. John's installed an extraordinary set of windows for the nave between 1885 and 1888 designed by Pernlochner for the Tiroler Glasmalerei, Innsbruck. The church of St. Francis de Sales was completed between 1898 and 1911 with a large series from Mayer and Co., Munich.

The Mid-West and German immigration

German Catholic and Lutheran populations had already achieved considerable importance in the Mid-West in the beginning of the 19th century.35 The Mid-West glazing traditions were similar to those in the East, but from continental sources, not English. Often the glass painters, like the clergy were immigrants [See similar phenomenon of German artistic influence in Eastern Europe]. Henry Burgund of Cincinnati, one of the first recorded producers of stained glass, was an immigrant. He advertised in the Cincinnati Directory as a "glass stainer" beginning in 1855. His work included the chancel windows of the Fourteen Auxiliary Saints (Vierzehnheiligen or Vierzehn Nothelfer) for St. Boniface Catholic Church in Quincy, Illinois, now destroyed.36 The windows were installed in 1870, after the designs of William Lamprecht, also of Cincinnati, and an ethnic German. The 1869 remodeling of the 1848 church was directed by the Benedictine Brother Adrian Wewer, who was the architect of several Catholic churches and most of the buildings on the Quincy College campus in Quincy.37

Francis G. Himpler, St. Joseph's Church, Detroit

Michigan, nave looking west.

Photo: NheyobThe German-Catholic church of St. Joseph in Detroit possesses early German windows that demonstrate the ability to integrate decorative forms in glass, sculpture, and architecture that made these studios so successful.38 St. Joseph's was designed by a German-born architect Francis G. Himpler of Trier, who had studied architecture at the Royal Academy of Berlin 1854-58. The large brick Gothic Revival structure evokes the German hall church design. The cornerstone was laid in 1870 and the dedication took place in 1873. Typically, the windows of the chancel were the first installed, after designs by the architect. The geometric patterns are shown in color on the original drawing labeled "Chancel Windows, St. Joseph's Church, Detroit Michigan, New York, Febr. 11, 1873, Fr. G. Himpler Architect".39 The designs were sent to the

Francis G. Himpler, Designs for chancel window

ornamental panels, St. Joseph's Church,

Detroit, 1873, Church of St. Joseph,

Detroit. Photo: William Worden Mayer studio of Munich, whose signature in German, Mayer'sche Kunstanstalt Munchen, appears on the inscription band of the central window.40 The tall narrow lancets of the chancel, like the church itself, evoke German medieval models. The tapestry pattern at top and bottom, enclosing figures framed in architectural canopies, was known to architect and 19th-century audience alike through medieval precedents as widespread as Cologne cathedral in the Rhineland, St. Thomas church in Strasbourg in Alsace, Regensburg cathedral, Bavaria, or Heiligenkreuz, Austria. A comparison of St. Joseph's windows with the early 14th-century window of

Cologne workshop, clerestory windows north

choir, before 1311, Cathedral of Cologne.

Photo: authorstanding kings in the choir clerestory of Cologne cathedral, demonstrates these generic qualities. The figure and decorative elements of the window are treated as a whole, the non-figural elements acting as both a frame for the image and as a means of integrating the fictive architecture with the real architecture of the building. Both medieval and modern figures occupy niches with cusped arches crowned by tall pediments. Pierced and foliate, the arches form a lacy frame further relieved by the deep colors of the diaper pattern behind them. Enclosing the entire architectural and figural design are glass patterns of geometric and vegetative ornament. Quatrefoil or cinquefoil designs framed by flat border appear in both the medieval and modern glass. Realistic leaf patterns in St. Joseph's have their models in the ivy leaf patterns in the border and cinquefoils of Cologne. The three-dimension treatment of the figure by Mayer, naturally, forms a distinct contrast to the flatter medieval rending of the figure.

St. Joseph's windows repeat the decorative patterns of the furniture a condition obviously viewed as appropriate by architect and client. The Gothic towers above the tabernacle and the ends of the altar employ the same tall, narrow pointed arches and crochet finials as those of the glass. The pierced quatrefoils at the top of the altar, running at the same level as the angels' pedestals, echo the quatrefoils in glass immediately behind them. The window's intersection of three dimensional or "academic" images with the abstracted linear forms of architecture is repeated by the chancel wall and altar. Framed in niches, perched between towers, or set upon wall sconces,

Mayer and Company, Munich, Christ gives Keys

to St. Peter, 1873, Church of St. Joseph,

Detroit. Photo: author

the figures become as much architecture as image. The windows are linked further to the chancel space through the interpenetration of color. The large expanse of white glass allows sufficient light to animate the gold gilt of the altar and the tints of the statues and woodwork. The result is a highly interactive, light, but color-flecked space, highly typical of 19th-century Catholic sacral ambiance.

Many other Mid-West cities, such as St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Chicago show similar works of ethnic construction and imported continental forms. The long history of ethnic immigration has produced in Chicago one of the richest examples of Catholic church building and the dominance of the "Munich School" as the studios of choice.41 Three different examples may give some indication of the extraordinary vitality of the city's ethnic building at the turn of the century, the German parish of St. Paul, the Polish Parish of St. Stanislaus Kostka, and the church of St. Vincent de Paul staffed by the Vincentian Order to serve a predominantly Irish congregation. All the major windows in these buildings were commissioned from German or Austrian studios. Detailed discussion of these buildings, almost non-existent in scholarly literature on American art, may enable the reader to appreciate the intensity of the link between church building and social issues.

St. Paul serving German Catholics of Chicago

The church of St. Paul, 2234 South Hoyne Street, is the smallest, seating 700 people, but the most architecturally distinctive. The first German Catholic

Henry Schlacks, Church of St. Paul,

1897-1899, 2234 South Hoyne Street,

Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguin parish of the city, St. Peter's, had been organized in 1846 and administered by an Alsatian priest Rev. Johann Jung.42 St. Paul was founded in 1876 to serve an enclave of forty German families who had immigrated from the Moselle Valley and the Rhineland. The ethnic-German parish was circumscribed on the west by the south branch of the Chicago River and on the south by 18th Street, and located within the boundaries of the English-speaking parish of St. Pius. The first pastor of St. Paul's was the Rev. Emmerich Weber, a native of Trier, and a Rhinelander like his parishioners. Weber supervised a growing parish and supported construction of a variety of buildings for church services and classrooms for the developing school. In 1888 Fr. Weber was given charge of founding another new parish in Illinois and Rev. George D. Heldmann was transferred from his post at St. George's Church in Chicago to St. Paul's.

F. X. Zettler Company, Munich, St. Paul

Preaching in Athens, 1901, nave, Church of

St. Paul, Chicago. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

Heldmann appears to have been a brick and mortar priest. He began the parochial school building in 1892, turning to the newly founded firm of Schlacks & Ottenheimerfor the design.43 The three-story brick building was brought to completion within a year. Three years later Heldmann began the church, again turning to Henry Schlacks, architect, to construct a building of fireproof design which also recalled for the immigrant parishioners the churches of their German homeland.44 The choice of Schlacks is as typical of Catholic patronage as was the organization of ethnic parishes and the importation of continental stained glass. Schlacks was a native of Chicago who had begun his architectural training in the firm of Adler & Sullivan, the Chicago firm responsible for building some of the most progressive buildings of the era.45 Schlacks augmented this practical training with two years of formal instruction from 1888 to 1890 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and extensive travel in Europe.46 In 1892 he set up a practice with Henry Oppenheimer, also an ethnic German, who had been a draftsman with Adler & Sullivan. The partnership lasted for five years and then he practiced alone, employed by the archdiocese in the designing of Catholic schools and churches. The key to Schlacks' success, as it was for Patrick C. Keely and other architects of America's Catholic community, was his ability to submerge individual expression in the service of a corporate client. This client was concerned with

Henry Schlacks, Interior, toward chancel,

Church of St. Paul, 1897-1899, 2234 South

Hoyne Street, Chicago. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin cost effectiveness and solid workmanship but also with the political necessity of producing buildings that evoked in their eclectic diversity the variety of constituencies that formed the Catholic community. Thus the Poles needed to have buildings that spoke of their own ethnic roots, the Germans of their Rhenish background, or the Irish, buildings that distinguished them from American Protestant imagery.47 It is precisely this placing of the patron's needs over the architect's personality that has made study of such architects and their production so difficult for the biographical and monographic oriented approach of most past scholarship.48

The cornerstone for St. Paul's was laid in October 31, 1897 and the method of construction deserves special comment. Peter B. Wight, the architect known for his contribution to fireproof construction, recorded that Fr. Heldmann and Schlacks had made a tour of large cities in United States to evaluate extant churches. Heldmann, very probably to his superiors' discomfort, did not confine the study to Catholic churches, and praised Episcopal churches for "sincerity of purpose . . . and a truly religious character in their architecture, materials, and construction."49 Heldmann also expressed concern over the vulnerability to fire of many of the buildings they saw. Thus, for reasons of aesthetics, spirituality, historical context, and safety, Heldmann and Schlacks agreed on brick as the dominant building material. Terra cotta, also a clay material, was used for window tracery, capitals of the columns, the keystones of the vaulting and other minor decorative areas. Wood and plaster was avoided and steel limited to the framework supporting the tile roof. The reddish brown fire brick "to satisfy the eye" was produced by the Webster Brick Company of Webster, Ohio, and the building has subsequently achieved distinction in the popular category of uniqueness

Henry Schlacks, Detail, brick work, Church of

St. Paul, 1897-1899, façade, 2234 South Hoyne

Street, Chicago, Illinois. Photograph: authorreflected by its listing in Ripley's Believe It or Not as "the church built without a nail."50

Although Schlacks spoke movingly of his inspiration from medieval German churches and the contemporary work of Johannes Otzen, he must have been inspired as well by brick building in the United States.51 It was natural, however, for him to emphasize ethnic connections for his client. Ware and Van Brunt had built Harvard's Memorial Hall in a Ruskinian Gothic style in brick between 1866 and 1878 and Richardson's Sever Hall, at Harvard yard dates to 1880.52 Beautifully cast brickwork in the window moldings and string courses are particularly striking elements of Sever's design.53 It is inconceivable that Schlacks would not have been aware of these brick structures after his two years of study in Cambridge, in particular since Ware had been the founding professor of the architectural course at MIT.54

At St. Paul's the brickwork is magisterial. As at Sever Hall, the continuity of support system into decorative

Henry Schlacks, Nave, Church of St. Paul,

1897-1899, 2234 South Hoyne Street,

Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguin embellishment fuses the issues of practical and decorative so that the two become inseparable, indeed, interactive aspects of construction. Schlacks, reputedly because of the inability of local construction companies to understand an all brick construction and the lack of funds, acted as both architect and contractor.55 The fusing of the position of architect and contractor, approximated, as has been suggested, the medieval office of magister opus, or master of the work, responsible not only for the design of the building but the implementation of the design through all stages of construction. Stories of medieval townsfolk contributing to the construction of cathedrals, based on promulgation of legends such as the "Cult of the Carts at Chartres" have been

F. X. Zettler Company, Munich,

St. Boniface, 1897, chancel,

Church of St. Paul, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin

F. X. Zettler Company,

Munich,

Christ in

Gethsemane

(Agony in

the Garden), 1902,

transept,

Church of St. Paul,

Chicago.

Photo: Michel M.

Raguin challenged in later scholarship.56 For the construction of St. Paul's, however, community donation "in-kind" appears to be a documented reality. Many of the members of the parish of St. Paul were bricklayers and masons by trade and Schlacks arranged to hire them at prevailing wages "so that in many cases what a man contributed might come back to him."57 The vaulting is particularly impressive. The structure is a true brick vault, with the ribs as well as the vaults themselves constructed in traditional medieval methods, that is, without steel supports. Thus the church of St. Paul represents that unusual structure combining harmonious design, refined construction, and extraordinary patronage.

St. Paul’s interior decoration

F. X. Zettler Company,

Munich, St. Peter, 1897,

chancel, Church of St.

Paul, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M.

Raguin. The firm’s

signature is in the lower

left architectural frame.

The embellishment of the interior was executed over some time.58 The windows, however, were commissioned close to the time of the construction. Inventories kept by the F. X. Zettler Company of Munich list the apse windows as having been completed in 1897 and the rest of the windows executed in 1902.59 [See Appendix] The apse series contains an image of the risen Christ flanked on the left by one of St. Peter and on the right by St. Paul. The signature of the studio, F X ZETTLER MVNICH is located in the architecture below the inscription St. Petrus. To the sides appear saints of local devotion such as St. Boniface, the first apostle to the Germans, and St. Elizabeth model of charity and also patron of the Teutonic knights, whose tomb was in Marburg. The transepts contain scenes from the life of Christ popular in the 19th century. Beginning on the north, we see the Adoration of the Shepherds, the Boy Jesus preaching in the Temple, and the Marriage at Cana and on the opposite wall starting from the altar, Christ Preaching to a Crowd, the Agony in the Garden, and the Resurrection. These scenes resonated with the public, all, save the Resurrection, are moments when Christ’s human nature is center stage.These scenes resonated with personal memory of similar events, such as the awkward moment of the wine running out at the wedding at Cana. Christ accedes to his mother’s wishes, and aids the embarrassed family. Zettler’s designers give the viewer meticulous,human detail, such as the wine steward tasting the transformed water into wine before the youthful couple.

The windows emphasize human emotion. Facial expression, dramatic shifts in the torsion of the body, and contrasting colors in the glass define the action for the viewer. A detail of the Resurrection is a touchstone. Silhouetted against a golden sky, suggesting the rising of the sun as a symbol of the rising of the Son of God, an angel adores the risen Lord. The face is youthful, framed by curling locks. The heavenly being wears liturgical raiment; a damascene cope with pearled edges in red is set

F. X. Zettler Company,

Munich, Resurrection,

detail of angel and

sleeping soldier, 1902,

transept, Church of St. Paul,

Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin against blues tones of the

F. X. Zettler Company, Munich,

Wedding at Cana, detail of the

wine steward tasting the water

transformed into wine, 1902,

transept, Church of St. Paul,

Chicago. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

wings. Below, confusion reigns. The soldier guarding the tomb is astonished and fearful, a contrast to the composure of the adoring angel. Six nave windows recount the story of the church's patron in similar terms: the Conversion of Paul, Paul preaching in Athens, Paul before a Roman magistrate, Peter and Paul meeting in Rome, Paul praying in prison and finally, his Execution by the sword. Save for the divine intervention depicted in Paul’s conversion, the episodes are real-life moments with which the parishioners can empathize. In prison, for example, Paul kneels with his hands clasped in front of him. His gray bead marks him as someone who has known the passage of life. His intense gaze and well-defined face is echoes by the sculpted vigor of his garments. Details of the jug of water, the straw mat, and manacles add realism to the scene.

Schlacks remained particularly attached to the church of St. Paul throughout his entire career. He designed a three-story brick rectory built between 1901 and 1902. He also designed the marble main altar for the church, executed in Italy by installed in 1910, and the communion rail installed two years later. Sometime close to this date, there must have been the installation of the impressive high marble reliefs of the stations of the cross and the statues set on the

St. Joseph presenting Pope Leo

XIII, chancel mosaic, 1922-30

after original designs of 1900,

Church of St. Paul, Chicago,

Illinois. Photograph: Michel M.

Raguin

Leo XIII issued the

Encyclical Quamquam Pluries

urging devotion to St. Joseph.

August 15, 1889: [Joseph]

should be regarded as the

protector and defender of

the Church, Fathers of families

find in Joseph the best

personification of paternal

solicitude and vigilance;

spouses a perfect example of

love, of peace, and of conjugal

fidelity. [For] artisans and

workmen [he is an example for]

imitation.

F. X. Zettler Company, Munich,

St. Paul in Prison, detail, 1902,

nave, Church of St. Paul,

Chicago, Illinois. Photograph:

Michel M. Raguinpillars and on the choir loft railing of the church. In 1922 Schlacks worked with the pastor Rev. Leonard Schlim to complete the mosaic decoration for the church which had been a part of the original designs. The Venetian firm of Cav. Angelo Gianese Company executed the mosaics, such as that showing St. Joseph presenting the pope Leo XIII, which were installed in 1930 by John Martin of Chicago. The present building has suffered minor losses such as the original chandeliers and illuminated crosses that once graced the two towers of the facade. Nonetheless, St. Paul presents a splendid example of confidence by an ethnic minority at the turn of the century. The old world, indeed, appeared to have been reconstructed on new and fertile soil.

In the parish census of 1900, 4,000 persons belonged to the parish of St. Paul and 726 children were enrolled in the parochial school. The community was thriving, but also changing and its monolithic ethnic composition had become more diversified. It is significant to note that the establishment of new parishes after St. Paul's followed ethnic divisions. As other settlers began to inhabit the region, a Slovenian parish was established as St. Stephen's, Italians were given St. Michael's, and for the Lithuanians, Our Lady of Vilna.60

St. Stanislaus Kostka serving Polish Catholics of Chicago

The Poles in Chicago had almost as long and powerful a history as the Germans.61 St. Stanislaus Kostka was the first Polish parish established in the city, not without some rather spectacular conflicts between the bishop and parishioners. The church began through lay initiative with the

Patrick C. Keeley, Church of

St. Stanislaus Kostka, 1877-

1881, façade. 1351 W

Evergreen Ave, Chicago,

Illinois. Photograph: Michel M.

Raguinorganization around 1864 of the St. Stanislaus Kostka Benevolent Society.62 In 1867 the society purchased land and in 1869 began a two-story frame structure.63 At the same time the society contacted the Resurrectionist Fathers in Rome and ultimately obtained the appointment of a Polish priest for the Chicago parish.64 Fr. John Wollowski and an assistant arrived on November 1, 1869 to learn that the bishop had already appointed a diocesan priest, Joseph Juskiewicz to the post. After almost a year into Juskiewicz's tenure, a vocal faction took matters into its own hands and six men beat the appointee and insisted that he resign. Juskiewicz subsequently left Chicago for an appointment in Pennsylvania. Rev. Adolph Bakanowski, of the Resurrectionist Order originally contacted by the Stanislaus

Patrick C. Keeley, Church of St. Stanislaus

Kostka, 1877-1881, detail of statue of

Stanislaus Kostka on façade, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Kostka Benevolent Society, accepted the vacated post and reconciliation began between parish and bishop. The title to the church, which, in an early effort of lay autonomy, had been in the hands of the Benevolent Society, was transferred to the bishop as Corporation Sole. The bishop then agreed to consecrate the church, the dedication taking place on June 18, 1871. The New Chicago Times article reflects the complexity of the situation. "The Polish church, on the corner of Bradley and Noble Streets, which was the bone of contention between the pastor and congregation last fall, was consecrated . . . by bishop Foley and 200 members were confirmed. Three sermons were delivered during the exercises, one of which was in English, one in German, and the other in Polish." Subsequent to the visit of Jerome Kaisierwicz, General of the Resurrection Order, in July 1871 an agreement was reached that gave the Resurrectionists the right to staff all Polish parishes in the Chicago for 99 years.65

Only a few years after the controversial dedication, the original building was proving too small for the growing parish. The present church of St. Stanislaus Kostka was begun in 1877 after the designs of Patrick C. Keely.66 Completed in 1881, its construction took place under the pastorate of Rev. Vincent Barzynski who was one of the founders of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America (PRCUA) and who founded a number of Polish parishes in Chicago, including St. Hedwig, St. John Cantius, St. Stanislaus Bishop & Martyr, St. Hyacynth, and St. Mary of the Angels.67 It is important to realize exactly how impressive these institutions were around the turn of the century. By 1897, the parish had developed into the largest Catholic parish in the United States with over 8,000 families and 40,000 people. Despite several splits in the congregation, in 1908 the parish still numbered almost 5,500 families and taught 4,500 children in its parochial school.68

The church itself, modeled on Baroque models of central Europe, is a highly imposing

Patrick C. Keeley, Church of St. Stanislaus

Kostka, 1877-1881, interior looking towards

chancel, Chicago. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin structure capable of seating 1,500. A single massive central vessel supported by tall marble columns defines both the spatial and pictorially didactic potential of the building. The aisle windows [See Appendix] were installed probably between 1903 and 1905,

Annunciation, First of the Joyous Mysteries of

the Rosary, 1881, Church of St. Stanislaus

Kostka, Chicago. Photo: Michel

M. Raguin and have for their subject the mysteries of the rosary.69 In one of the window, St. Dominic kneels before the Virgin Mary while the Christ Child blesses him and presents him with the rosary. Each mystery is identified by color in a bouquet of roses at the base of the window, white for the Joyful, red for the Sorrowful, and yellow for the Glorious mysteries. The windows' design reflects to the Baroque model for the building as a whole. An ornate niche framing a brightly colored scene of one of the fifteen subjects of the rosary meditation commands the center of the window. The architecture combines fictive and as well as representational elements, varying highly ornamented pilasters and columns that support vaults over which a solid or pierced canopy is raised. The niche is floated

St. Dominic Receiving the Rosary,

1881, Church of St. Stanislaus Kostka,

Chicago, Illinois. Photograph: Michel M. Raguin against a yellow background embellished with exuberant swaths of curving white foliage. The whole is bordered by a darker band of color and framed by alternating ovals and bands overlapping a strip of blue glass embellished with repeating circles. The lower central panel of the window contains the lavish bouquet of roses over the name of the donor in Polish.

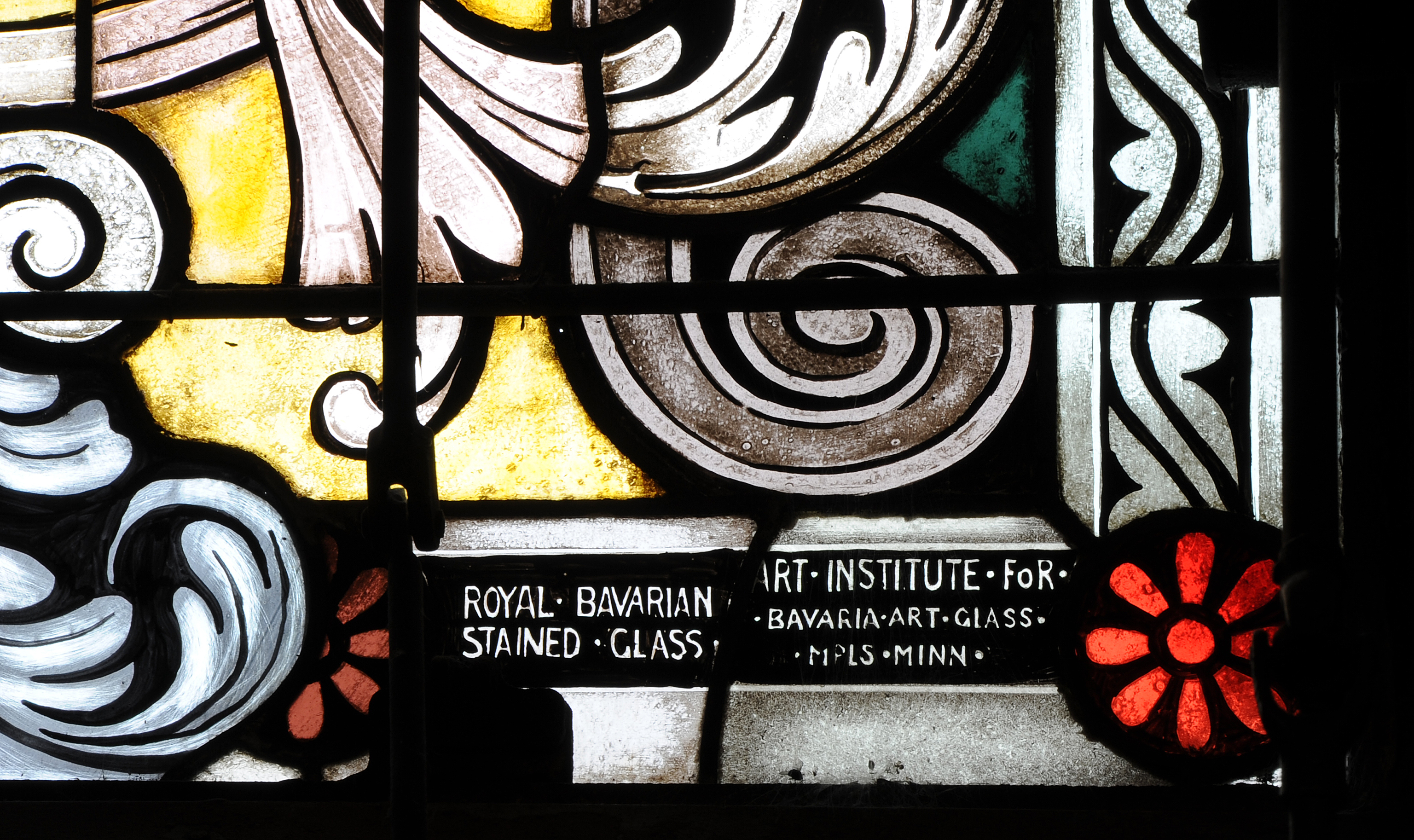

The windows as a whole form a vast light-filled wall of silver and gold highlighted by the deeper accents of the border and figural scene. The rounded forms of the windows and the tracery echo the rounded arches between the columns and the vault. Below are the signatures Royal Bavarian Stained Glass/Art Institute for Bavaria Art Glass Studios, Mpls., Minn. Current thought suggests that this name was a marketing strategy for the Tyrolese Art Glass Company (Tiroler Glasmalerei Anstalt or TGA), and F. X. Zettler There are no records that his company actually operated from Minneapolis; it was rather a legal name through which both F.X. Zettler and TGA marketed work in the United States.70

Above the windows, and benefiting from the high level of light, are murals describing the events in the life of St. Stanislaus Kostka, a young Polish nobleman who died as a Jesuit novice in 1568. The Jesuits had been granted the authority of a Roman Catholic order only in 1541, so that Stanislaus Kostka remains not only a Polish hero, but one of the first luminaries of the Society of Jesus. At the age of sixteen he is reputed to have ha

Church of St. Stanislaus Kostka,

1877-1881, detail chancel painting,

Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguin d the vision depicted in a painting above the church's altar. The Virgin placed the infant Jesus in his arms and told him to join the Jesuits, which he accomplished only after walking halfway across Europe.71

Window Signature, 1881, Church of St.

Stanislaus Kostka, Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguin

The huge mural filling the dome of the apse, in accordance with the devotion of the Resurrectionist Fathers, depicts the Resurrected Christ. Painted by the Polish artist Thaddeus Zukotynski, the image is a vastly expanded version of the theme, reminiscent of Raphael's Vatican painting of the Disputation over the Blessed Sacrament. Christ is surrounded by a crowd of the blessed from all periods of history. One can easily recognize the horned Moses, the Old Testament heroine Judith who slew Holofernes, John the Baptist, and St. Peter. In the crowd to the left, recent saints are more prominent, including the Polish queen, St. Hedwig, a Pope, St. Jerome, the author of the Vulgate Latin translation of the Bible, and several young Jesuits, led, undoubtedly, by Stanislaus Kostka. The extensive use of marble, gold leaf, and rich woodwork, combined with the painting on both opaque and translucent surfaces of walls and windows, makes St. Stanislaus Kostka an extraordinarily unified, if eclectic, space.

St. Vincent de Paul and the Paulist Fathers of Chicago

The parish of St. Vincent de Paul was founded in 1875 to serve a predominantly Irish Catholic population in the West Lincoln Park neighborhood.72 The present church was constructed between 1895 and 1897 after the designs of

James J. Eagan, Church of St. Vincent de Paul,

1895-1897, façade, 1010 West Webster Ave.,

Chicago. Photo.: Michel M. RaguinJames J. Eagan. Born in Ireland and educated in England, Eagan came to the

James J. Eagan, Church of St. Vincent de Paul,

1895-1897, chancel, Chicago..

Photo.: Michel M. RaguinUnited States as a youth and trained in several New York architectural offices, including those of James Duckworth and Richard Upjohn, both of whom were known for their work in ecclesiastical design. Immediately following the Great Fire of 1871, he established a practice in Chicago and was active in reconstruction work.73 Although often described as in a French Romanesque style, St. Vincent de Paul is not based on any specific French 12th-century building, but rather uses isolated elements identifiable to the modern viewer as "Romanesque" as opposed to period styles such as Gothic or Baroque. Chief among these are the monolithic towers and the use of rounded arches repeated across the entrance portals, huge frame of the nave rose, and both blind and open arcading of the towers. The interior is organized around an unusually large, open space at the crossing. The rounded apse with elaborate altar, however, remains the focal point of the church. These stylistic choices served to evoke the French origins of the Vincentian Fathers who founded the parish. References to the Vincentian mission reverberate throughout the building both in form and in image [See Appendix]. The focus, as at St Paul’s, is affective viewing, themes that resonate with the daily lives of the parishioners. One wall holds a painting of the Death of St. Joseph. Framed by the architecture, it is

Church of St. Vincent de Paul, Death of

St. Joseph,

wall painting, Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguin integrated in the decorative schema of the church. As already noted at St Paul’s, Joseph was promoted during the latter half of the 19th century as a

James J. Eagan, Church of St. Vincent de Paul,

1895-1897, interior, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinmodel for working class male behavior, and as exemplifying the promise of the Church for a peaceful death in the presence of his foster son, Jesus.

The stained glass was installed from 1896 through 1901 by the Munich firm of Mayer and Company, in form close to the dense pictorial illustrations familiar from the windows of St. Paul's.74 The great windows of the north and south transept are dedicated to Christ and his servant on earth St. Vincent to Paul. The image of St Paul being received into heaven surrounded by angels is taken from a 17th-century print source. The studio was peculiarly

Mayer and Company, Munich, Angels Receiving

St. Vincent de Paul, 1896-1901, north transept,

Church of St. Vincent de Paul, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinsensitive to the interplayof uncolored (grisaille glass) and saturated color. Thus the windows are convey the natrrative over considerable distance as well as letting in sufficient light to the interior. Scenes from the life of St. Vincent de Paul (1581-1660) who championed the cause of helping the poor and marginalized and established the Sisters of Charity. Across

Mayer and Company,

Munich, St. Vincent de Paul, Protector of

Children, 1896-1901, north transept,

Church of St. Vincent de Paul,

Chicago. Photo: Michel M. Raguinthe church, the south transept rose presents Christ seated in majesty, similarly surrounded by angels. Below him are scenes of St. Peter, the martyrdom of St. Stephan and the life of Paul.

The windows in the nave, although of particularly fine execution, are typical of the thousands of commissions executed by German and Austrian firms for their American patrons. Key to their effectiveness were their placement and implicit understanding that viewers would be addressing these images with very personal intentions. Subjects such the Marriage at Cana, the Flight into Egypt, Adoration of the shepherds, Christ discovered by his parents while teaching in the Temple, Christ as an adult preaching to the people or among the little children, were seemingly obligatory for these modern Catholic buildings. Not only were subjects

Mayer and Company, Munich, Christ enthroned

above scenes of Saints Peter, Stephen, and

Paul, 1896-1901, south transept, Church of

St. Vincent de Paul, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinsimilar, but through the replication of so many of these windows across the country, the compositions and even the cast of characters in these translucent dramas promulgated a consistency of Catholic form.

The elaboration of the scene of the Marriage at Cana may serve as an example of the function of such images. Christ responds to his mother's request that he help the embarrassed newlywed who has run out of wine at the wedding feast. Christ and his mother sit at the foot of the table closest to the viewer. With a gesture of authority Christ instructs the young kneeling servant to pour water into a wine jar. As the liquid flows from the neck of the vase it changes from white to red, allowing the viewer to participate in the moment of the miracle. The depiction of all aspects of the scene is highly detailed. At the head of the table, under a scarlet canopy, the young bride is appropriately demure, her head encircled with a crown of white roses. The bridegroom, depicted with a smooth cheeks and youthful mustache, appears anxious concerning the shortage of provisions for the guests. In the background, hurrying away from the table is a servant whose arms

Mayer and Company, Munich, Marriage

at Cana, 1896-1901, south transept,

Church of St. Vincent de Paul, Chicago.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin are laden with the dishes she has just cleared. All these events, a mother's request to a grown son, a family's distress, the busy labor of feeding guests on festive occasions are all of immediate and personal issue to the receptive viewer. By such devices, the building projected the message of the humanity of Christ. It articulated clearly and convincingly the bridge offered by the institutionalized church to its parishioners that could link their lives with the life of the Savior.

Conventions of the figure rendered in realistic space

The 19th-century German painters, and to some extent the French studios, were deeply imbued with a vision of the figure rendered in realistic space according to the canons of perspective established in the Italian Renaissance and informing academic schools of art from the 18th through the early 20th century. They are also indebted to the last great flowering of the art of glass painting in German-speaking territories produced by the circle of artists around Albrecht Dürer in Nuremberg or the glazing studios of the Rhineland, such as the panels from the

Cistercian abbey of Mariawald, The Return from

Egypt of the Virgin, Joseph, and the Christ Child,

1522-26, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Photograph: authorCistercian abbey of Mariawald, The Return from Egypt of about 1522-26 exemplifies the solid modeling and bold graphic systems that characterized German prints of the time. Examples of these works are found in American collections, for example, the panel of the Journey to Bethlehem from the Rhenish abbey of Steinfeld, dated about 1527, now Harvard University Art Museums.75 These Renaissance panels show a considerable amount of white glass balanced by areas of strong color, three dimensional modeling of forms, and an illusionistic recession in space. One need only compare St. Paul Preaching in Athens from the Church of St. Vincent de Paul in Chicago with the Mariawald panel to appreciate how the revival glass repeated the Rhenish delight in detail of landscape, expression, clothing.

The German-Catholic rendering forms in space, is an extension of the painting of the time as well. Von Leonhardshoff's Death of St. Cecilia shows the same soft, flawless surfaces as the Holy Family or Doubting Thomas in Boston's Holy Cross cathedral or as the angels appearing to Abraham's hand in Providence's St. Paul's Cathedral. The enamel colors sometimes used in the glass are technically quite sophisticated, often necessitating numerous firings, and had been developed from the techniques used in porcelain manufacture. Even more impressive, perhaps, is the tenacity of the Nazarene style in the idealized faces, monumental drapery, and graceful interaction of figures seen in all of these new world manifestations. The unity of Catholic sentiment and German-inspired painting style remained strong long throughout the first quarter of the 20th century. The German studios had demonstrated a high technical expertise and sensitivity to Catholic iconographic demands. Imported windows or those produced by transplanted German-trained artists continued to be favored by many American dioceses. The three studios discussed continued to provide very large numbers of windows during the 20th century. New studios in the Munich tradition even began.76

Emil Frei demonstrates the issue of the interchangeable of the imported and native German product. Frei, after training in Munich with Mayer & Co., set up his own studio in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. His windows retain all of the compositional devices and technical processes that are hallmarks of the Munich style.77 In many instances, the windows were fabricated in a Munich branch later established by Frei and managed by Emil Hoffman until well into the 1920s.78 As discussed earlier, after initial patronage of French glass painters, Catholics in New Orleans commissioned almost exclusively from German or Austrian studios. Frei executed a great many windows for New Orleans churches, distinctive among them a series completed in 1922 for the church of St. Francis.79 The windows depict Catholic doctrinal priorities, in particular the Sacrament of the Eucharist and specific Franciscan imagery. [See Appendix]

These European studios continued to be major competitors for the emerging American stained glass manufacturers, and America saw the predicable chauvinistic exhortations about the superiority of American products.80 Often, however, the precise identification of a native or European origin for commissions was confused by the strong links between the American firms and the foreign-trained artists and craftspeople they often employed. Studios also retained European branches, or subcontracted work to Europeans. For example, the large program of windows made by the Von Gerichten studio in 1921 for the French-speaking congregation of St. Joseph's church, Worcester, Massachusetts, was commissioned from the American-based studio but actually fabricated in Germany.81 The church contracted for the windows with the representatives from the studio, located in Columbus, Ohio. Von Gerichten also continued to maintain a branch in Munich, where, presumably because of the pattern of business, the windows were designed. Records in the studio, now unavailable, may have indicated this transaction, but the records retained by the church do not indicate that the church officials knew, however impressed they were the quality, that they were getting foreign imports. 82

Glazing studios of this time were highly flexible. The Ford Brothers of the Mid-West advertised themselves as "makers of all style of Catholic church windows.83 Their catalogue included English and German styles, both identified as "windows in the style of the middle Fourteenth Century as executed . . . by artists of European training and experience."84 The Ford Brothers’ commission for Emmanuel Church in Shawnee Oklahoma shows not only the Nazarene style but a composition taken from the German painter Bernhard Plockhorst whose biblical illustrations were standard fare among many Christian congregations.

Ford Brothers, Holy Family,

Emmanuel Church, Shawnee

Oklahoma. Photo: authorIn the 20th century we know that European studios provided windows sold through American firms, for example windows by the Van Treeck Studio of Munich commissioned by the Conrad Schmitt Studio, Milwaukee, for a large number of churches in the mid-West in the 1920s.85 Thomas & John Morgan's windows for the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, Boston [See Appendix] and later work suggests that the firm employed, among others, Munich-trained craftspersons and/or subcontractors who could work in different styles.86

Studios also executed windows by independent designers. The phenomenon was current, as we have seen for even the largest and most prestigious of the studios such as the Tiffany Studio. Leo Dabo, a French born artist who had apprenticed with the J. & R. Lamb studio in 1884 and La Farge between 1885 and 1886, designed the decoration of St. John the Baptist Church, Brooklyn, a congregation connected to St. John's College and seminary. In the 1894 dedication booklet, Dabo (with his brother Theodore Scott Dabo) advertised as "artists and ecclesiastical figure painters, decorators of St. John the Baptist Church." The Morgan Brothers were the fabricators for this commission, advertising in the same dedication booklet as "manufacturers of fine art glass," and citing the windows in St. John's as an example.87

These European continental studios and their American offshoots were to be challenged by two phenomena. First was the international crisis of World War I, paralyzing imports, and afterwards making the German-made import a problematic issue in sales. Secondly, America began to develop in two new and distinctive stylistic directions. A trend of windows inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement was primarily restricted to wealthier English-tradition clients and secular installations, although the Irish Art and Crafts products were also patronized by American Catholics. For religious commissions, however, a far more serious challenge was the growth of the Second Gothic Revival, championed by architects such as Ralph Adams Cram and studios such as Charles Connick. A moral fervor permeated the proponents of this 20th-century revival style, in a manner that seriously challenged the pictorial "Renaissance" mode of the Munich school and similar productions. Romanticism in a new guise, the Second Gothic Revival argued for a return to "true principles" of religion and art embodied in a style that, as seen for the First Gothic Revival in Europe, was believed to uniquely insinuate the worshipper into prayerful space. Only when these studios emerged in the 20th century did serious competition face the Continental style among Catholic patrons.

REFERENCES

![]()

2. ^ Osterreichische Galerie, Vienna, Inv. Nr. 5327. Andrews 1964, p. 38, fig. 32a. Von Leonhardshoff was an Austrian artist who joined the Nazarenes in Rome at the age of 19. The painting of St. Cecilia is typical of the Nazarene philosophy in that it is based on Italian or Northern Renaissance prototypes. The model for the dying saint is the marble sculpture by Stefano Maderno made in 1600 for the church of St. Cecilia in Rome representing the position of the saint's corpse when her tomb was opened in 1599. . See Dietrich Schneider-Henn, "Die Tiroler Glasmalerei im Zeitalter der Weltausstellung," Antiquitäten-Zeitung No. 16 (1983), esp. XII-XV and XX. The participants given are Prof. C. Jele (director), Franz Pernlochner (history painter), Felix Schatz (history painter for the rose windows), , Heinrich Sieber (painter), Ferdinand Kessler (artist), Josef Schmid (architecture), and Rupert Schwarzenberger (architecture). The terms historian and painter appear to designate the iconographer and designer of the windows. The figural portions of windows were separated from the ornamental work which was accomplished by artists assigned to the "architecture" of the window.

3. ^ Sturm 1982, pp. 15-6, fig. 14; Robert I. Gannon, S. J., Up to the Present: The Story of Fordham (New York, 1967), 36. Contemporary references to the windows have not been discovered in either the archives of the archdiocese or Fordham University.

4. ^ The windows appear to have been cut down for their present placement, but it is not known if the windows were ever installed in the cathedral. English taste was not opposed to this glass. The Ecclesiologist 8 (1848), 284 praised the windows in the Chapel at Dreux, "Much of the glass with which the windows are filled, painted at Sèvres, is excellent, the drawing good, and the colours brilliant."

5. ^ Sturm 1982, pp. 24-25. See the well-researched and illustrated blog by Margret Duffy on the French-speaking church of St. Jean Baptiste in Manhattan. The Renaissance-style windows were produced between 1912 and 1914 by the Lorin Studio (then headed by Charles Lorin).

7. ^ See a wealth of literature on ethnic integration in America. Jay P. Dolan, The Immigrant Church: New York's Irish and German Catholics, 1815-1865 (South Bend, Indiana, 1987, second printing).

8. ^ I am grateful to Susan Levy for information on the German commissions in New Orleans. The Mayer list of of commissions cites five windows for St. Paul's 1900/6. St. Michael's windows of 1912/5 were surveyed by The Census of Stained Glass Windows in America in 1990 by the team of Jennifer Cadero-Gillette and Virginia Raguin. Alicia Waldstein-Wartenberg, is writing a thesis on the Mayer studio and has communicated to the author through Elgin Vaassen. “To serve the American market that became more and more important for the firm, the Mayer'sche Kunstanstalt in 1888 opened its own branch in New York City. It was able to undertake all planning and setting up-work on site as well as small renovations. Yet, execution of the windows remained in Munich.”

Tiroler Glasmalerei, p. 96. In an effort to attract clients from Great Britain, the TGA, Mayer, Zettler, and other continental firms advertised that they could furnish windows in a true English style.

9. ^ Tiroler Glasmalerei, p. 96.

10b. ^ Farnsworth 1990.

11. ^ Farnsworth 1990, p. 284, citing Mary Louise Christovich and Roulhac Tolendano, eds. New Orleans Architecture, Fauburg Treme and Bayou Road 4 (Gretna, Louisiana, 1980). These early windows are no longer extant.

12. ^ The progress in recording French 19th-century stained glass has made great advances during the last decades. A pioneering step was the inventory accomplished by two years of advanced seminars at the Institut d'Histoire de l'Art of the University of Lyon II between 1979 and 80. See Catherine Brisac, Marie-Félicie Perez, and M. Daniel Ternois, "Les vitraux de XIXe siècle dans les Eglises de Lyon," Bulletin de la Société de l'Histoire de l'art français 1982 (Paris, 1984), 159-79. The Inventaire Général des Monuments et Richesses Artistiques de la France has been recording 19th-century stained glass selectively.

13. ^ Farnsworth 1990, p. 284, notes the signature.

14. ^ Identification by Peter Cormack and Martin Harrison, accomplished by viewing slides taken by Jean Farnsworth. For details of the firm see Harrison 1980, esp. pp. 80-81.

15. ^ Westlake 1881-94. The work was one of the first comprehensive studies of the history of leaded and painted windows. It became an absolutely essential reference for Gothic Revival studios. See further, The Second Gothic Revival and the Transformation of Taste.

16. ^ See Albert H. Brever, S.J., The Jesuits in New Orleans and the Mississippi Valley (New Orleans, 1924).