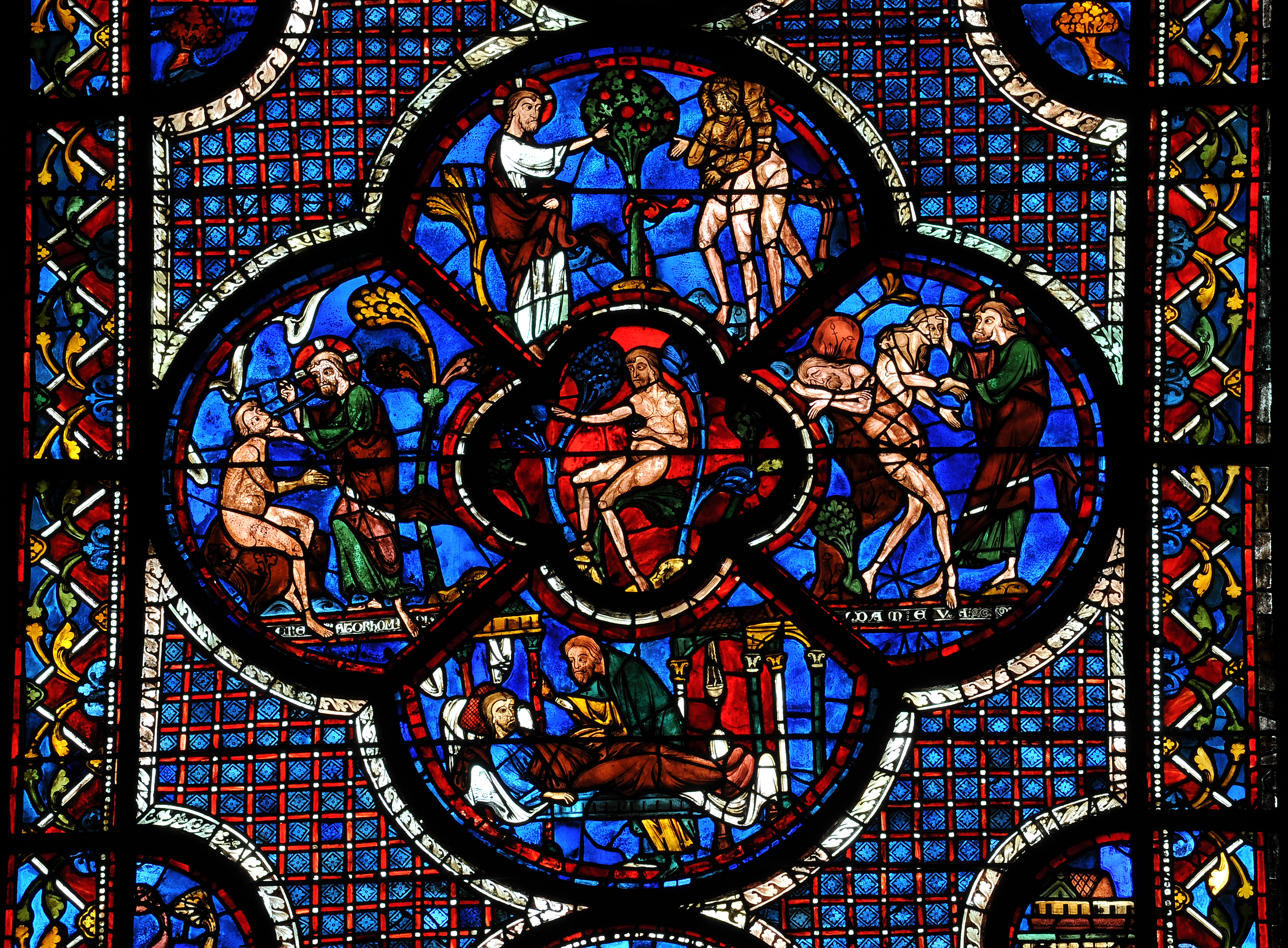

Sainte-Chapelle, Paris,

Crowning with Thorns,

Parisian workshop,

1242-1248. Photo: author The early years of the 20th century evidenced a deep interest in the Gothic as an ideal expression for architecture and also for glass. Many of the studios who developed in this direction had already been part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the transition was often gradual. To readers of 20th-century surveys such as John Gilbert Lloyd's Stained Glass in America or Charles Connick's Adventures in Light and Color stained glass windows are "naturally" based on the examples visible at Chartres or the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris.1 The universal spread of German and French traditional imports and American opalescent glass discussed in previous chapters is barely mentioned. The result is an unrealistic picture of the actual number, variety, and styles of leaded and painted windows in American buildings. Such advocacy, however, is understandable, for it parallels the early European writings on architectural stained glass by practitioners such as France's Eugène Viollet-le-Duc or England's August Welby Northmore Pugin.2 The studio head writes out of the tradition experienced by the studio, and both Lloyd and Connick were owners of studios engaging in the making of Gothic-inspired windows.

Changes at the turn-of-the-century

As more precise historical information became available to studios, they appear to have

Charles Eamer

Kempe Studios, Old

Testament Kings from

Tree of Jesse window,

1891, west window,

Church of the Advent,

Episcopal, Boston.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinbecome more explicit about the different periods they favored. The Kempe Studio of London, for example, was a thriving turn-of-the-century enterprise responsible for many programs in the United States, such as the great Jesse Tree of the Church of the Advent Boston in 1897 or the windows of the chapel of St. Ansgar and chapel of St. Boniface, St. John the Divine in New York in 1916 and 1918.3 Kempe’s style evoked 15th-century glazing and panel-painting traditions, exemplified by the Creed Window from Hereford Cathedral, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The English studios continued to interpret "medieval" in such heterogeneous terms, while the American studios were soon to develop a more exclusive definition of the Gothic.

Under the aegis of architects such as Ralph Adams Cram, a radical shift in the conception of the nature of medieval art occurred.4 As during the earlier Gothic Revival in England and France, a taste for art in an authoritative medieval style developed concomitantly with a more public interest in medieval art itself. The Architectural Record carried essays such as Caryl Coleman's "A Sea of Glass."5 The article is quite similar in intent to earlier English and French essays on medieval glass. The writer expounds the principles of the art by explaining the nature of the materials. The familiar injunctions of the mid-19th-century writers such as Edmund Lévy and Adolphe Didron about the moral basis of art reappear.6 The stained glass windows of the Middle Ages "were looked upon as the Bible of the poor and the uninstructed."7 To these authors, glass painting declined because the glass painters had become oblivious to the principles of bringing stained glass into harmony with architecture. "Abandoning the traditions of the great school of the 13th century they forgot the rule that all ornaments should consist of enrichment of the essential construction of the building . . . that the glazier cannot be successful where he acts independently of the architect."8 In the later Middle Ages (and by analogy, in the 19th century) "the abuse of materials, and the exaggeration of individualism were suicidal steps."9

Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue,

Interior looking towards chancel,

Emmanuel Church, 40 Dearborn

Street, Newport, Rhode Island.

Photo: authorEarly examples of Gothic inspiration: Harry Eldrich Goodhue and Wright Goodhue

One cannot overemphasize the role of the architect in the transformation of taste to focus on the Gothic style as inherently attuned to personal spirituality and also to the integrity of materials, a principle also evoked in turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts discourse. By the early 1900s, even at the height of the Opalescent, artists were increasingly interested in new expression. An early example of experimentation made possible by the collaboration of architect, patron, and designer is found in the astonishingly original chancel window in place by 1902 in Emmanuel Church, Newport, Rhode Island. The building expresses the perpendicular Gothic style familiar to English churches, undoubtedly something that felt at home to sophisticated Episcopalian parishioners. The window was a gift of Sophia Augusta Brown in memory of her sons, John Nicholas Brown and Harold Brown.10

The artist, Harry Eldridge Goodhue was the younger brother of the church’s architect, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, one

Harry Eldridge Goodhue,

Life of Christ, 1902, chancel,

Emmanuel Church,

Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin of the three partners in the prestigious firm of Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson.11 Harry had spent some time in Europe and returned deeply impressed by medieval windows. The

Harry Eldridge

Goodhue, Life of Christ,

detail Crucifixion, 1902,

chancel, Emmanuel

Church, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin intensity of the colors selected is reminiscent of the deeply saturated hues of the 13th century. He does organize the window into segments, but does not attempt the complex geometric patterns of those of the windows at Chartres, Bourges, or Canterbury. His bold draftsmanship stresses contour with very little three-dimensional modeling. Backgrounds are simple reds or blues and notably without any effects of “aging painting” as seen in the chancel window in St. James of the Less in Philadelphia. Goodhue’s figural proportions, however, owe much to Burne-Jones, although further abstracted. The figures are segmented with what would be illogically placed leads in comparison to a medieval model. The artist varied the tone of the segments the glass, particularly noticeable in the body of Christ. Here the 20th century artist deliberately emulates repair leads and mismatched colors often visible in ancient glass; such variations of color have occurred when medieval glass has been inexpertly restored over time.

Harry Wright Goodhue

Harry Wright Goodhue, Harry Eldredge’s son, one of the most promising members of the craft, never lived to see the full realization of his talent. Wright Goodhue (as he was usually referred to) showed a precocious ability to fuse revival and contemporary styles. The Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University honored his memory with an exhibition of stained glass and sculpture from March through April of 1932. Albert Franz Cochrane’s exhibition review illustrated two of his

Wright

Goodhue,

Dysmas [The

Good Thief],

choir clerestory,

St. James

Church, Roman

Catholic,

Wilkinsburg.

Photo: author cartoons from the “more than eighty” windows he designed for St. James Church,

Wright

Goodhue,

Apostles Simon

and Thaddeus,

detail of Creed

window, 1930,

St. James Church,

Roman Catholic,

Wilkinsburg.

Photo: author Roman Catholic, Wilkinsburg (greater Pittsburg), installed by 1930, a year before the artist’s death at the age of 26.12

Wright

Goodhue, St.

Mary Cleophas,

cartoon for St.

James Church,

Roman Catholic,

Wilkinsburg.

After Albert

Franz Cochrane,

"The Genius of

Wright Goodhue,"

Boston Evening

Transcript

(August

22, 1931), 9.

Wright Goodhue,

St. Mary Cleophas,

window 1930, choir

clerestory, St. James

Church, Roman

Catholic, Wilkinsburg.

Photo: author The extraordinary power of the attenuated graphic is revealed in a comparison of the cartoon and the final execution of the clerestory window showing St. Mary Cleophas. 13 Goodhue adroitly balances the lead lines of the diamond-shaped quarries against an undulating lattice to creating an active pattern that frames the deeply saturated central image. Cochraine praised Goodhue’s “freedom of modernism,” characterizing his art as “almost archaic in its simplicity [which] permits the broadest of treatment and almost complete flow of rhythmic line.” The depiction of the nude body of Dysmas, the Good Thief, from the choir clerestory achieves an expressive intensity; its placement of leadline recalls the non-anatomic divisions already seen in his father’s Crucified Christ in Newport. Examples of medieval glass with such repair leads and mismatched replacement glass can been seen in the figures of the injured wayfarer and Adam and Eve from the Good Samaritan window at Chartres.

Despite his short lifespan, Wright Goodhue accomplished much, often for buildings commissioned from the architectural firm of Cram and Ferguson.14 His windows showed a progressive adaptation of the abstract tendencies of 20th-century art, at first closely based on Arts and Crafts systems used by his father, Harry Eldridge Goodhue for the 1905 Corey windows in All Saints, Brookline, and the 12th- and 13th-century models published by Hucher, Viollet-le-Duc, and others. Those later were much bolder in their graphic simplicity, emphasizing rhythmic sweeps of curving line, similar to Arthur Dove's earlier abstractions such as Nature Symbolized of 1911 in the Art Institute of Chicago. Wright Goodhue's sculpture, another facet of his talents, was very contemporary, and close to the organic form envelope of the sculptor John Flannagan.

Collecting Gothic art and appreciation for the spiritual

The interest in constructing Gothic Revival buildings was supported by the growing taste for collecting 13th-century stained glass, a pattern that was observed earlier in Europe.15 In 1906 Henry Adams advised Isabella Stewart Gardner to purchase a large stained glass window from Soissons Cathedral, dated between 1195 and 1210-1215, now installed in the chapel of her Fenway mansion.16 Earlier, Mrs. Gardner's taste had gravitated toward more representational works such as the 15th-century panels originally from the cathedral of Milan that she acquired in 1875.17 The Milan panels demonstrate typical late Gothic conventions of three-dimensional modeling and incipient perspective. Mrs. Gardner's familiarity with this type of glass painting is confirmed by the similar conventions appearing in windows installed in the 1890s by Clayton & Bell, of London, in the church of the Advent, Boston, where Mrs. Gardner was a prominent patron.18

August Welby

Northmore Pugin,

Contrasted Residences

for the Poor, from

Contrasts: or A Parallel

between the Noble

Edifices of the Middle

Ages, and Corresponding

Buildings of the Present

Day; Shewing the Present

Decay of Taste, 1841.

Clayton & Bell,

Virgin and Child, detail

of Adoration of the

Magi, 1891, Church of

the Advent, Episcopal,

Boston.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin It was the moral fervor and the belief that Gothic principles were self-evident to the common man that gave much of this movement its strength, and also its poignancy. Pugin’s Contrasts: or A Parallel between the Noble Edifices of the Middle Ages, and Corresponding Buildings of the Present Day; Shewing the Present Decay of Taste. of 1841 had eloquently sounded a call for reform. The important English architect cast the modern world as one of uncaring exploitation of society for commercial gain, demonstrated by expedient and ugly buildings. The Gothic, he argued had the capacity to reawaking the spiritual values it embodied, when, he was convinced, societies’ rulers were subject to God’s call for charity and where art was conceived not for profit, but as service and praise. The Neo-Gothic was Romanticism in a new guise, a conviction that art can bring the soul, above all the "simple" soul into proximity with the divine. Such thinking dominated the stained glass revival as experienced by Europeans in the mid-19th century. It also permeated the early 20th century in America. The early literary and critical precedents were seized with renewed vigor by American architects and glass painters who saw themselves, at long last, able to speak the great language of the past. They read the same books and absorbed the same sense of mission, believing that the Gothic Revival could integrate the heterogeneous population of the new America into one spiritually uplifted community. America, for the Gothic proponents, had finally caught up with Europe, William Wordsworth's sonnet, At Furness Abbey of 1845 expressed 20th-century American attitudes toward the Gothic with perfect eloquence.

Well have yon Railway Labourers to THIS ground

Withdrawn for noontide rest. They sit, they walk

Among the Ruins, but no idle talk

Is heard; to grave demeanour all are bound;

And from one voice a Hymn with tuneful sound

Hallows once more the long-deserted Choir

And thrills the old sepulchral earth, around.

Others look up, and with fixed eyes admire

That wide-spanned arch, wondering how it was raised,

To keep, so high in air, its strength and grace:

All seem to feel the spirit of the place . . . 19

If the spiritual values of the Gothic form were inherent in the very nature of the style, its practitioners could claim much more than artistic or structural superiority. They could claim a divine mission, and Ralph Adam Cram's strength was his ability to press this point with singular fervor.

The wide-ranging influence of Ralph Adams Cram

Cathedral of Chartres, north aisle,

detail of Good Samaritan window, 1205-1215.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Cram's writings and his supervision of decorative commissions expounded not only the religious issues, but also the idea of the purity of materials and the search for the so-called true principles of glass painting developed by the Arts and Crafts movement. He differed from proponents of the Arts and Crafts movement in that he developed an extremely narrow definition of appropriate models and, in particular, the 13th-century French Gothic window as the primary source of inspiration.20 Cram, for example, characterized opalescent windows as inappropriate for a spiritual atmosphere and gave explicit directions to the studios working in his building. One can, perhaps, view him as an Americanized Pugin, in his belief in the existence of stylistic principles based on geographic, ethnic, and liturgical absolutes. Cram's antipathy for opalescent glass may very well have been associated with its ubiquity. Its very presence in lamp shades, row-house stairwells, or public theaters convinced him of its inappropriateness for the Church. How could Cram continue to believe in the moral implication of specific materials or stylistic choices if the same materials appeared so effectively in a myriad of settings?21 It bears noting that Cram's efforts began the 20th-century polarization that relegated the stained glass window to a church ornament. The "Quest for Unity" among the arts so evident during the opalescent decades, became a quest for separateness, a Protestant mode, a Catholic mode, a secular mode, and a myriad of subdivisions. And, again the architect exercised total control of the liturgical space. As has been so often the case with a revival style, we see a theoretical agenda taking precedence, with formal and aesthetic choices following. This split between stained glass as a fine art and stained glass as a religious expression remained as a general principle until the 1950s when a rebirth of stained glass became again linked to contemporaneous work in painting and the manufactured object.22

Gothic the current vocabulary

The triumph of the Gothic Revival was not without challenge. In 1903 Harry Eldredge Goodhue published an article in Handicraft magazine criticizing the contemporary opalescent style as not "stained glass, for it is absolutely different from what has been understood by the term."23 Sarah Wyman Whitman replied in a subsequent issue praising the experimentations of La Farge and the validity of the American contributions in new methods and expression.24 Opalescent glass continued to be commissioned, as evident from the many works completed by the Tiffany Studios after this date. The time of great innovation for the opalescent style, however, was over.

Boston saw the rise of large and influential studios working in a Gothic-Revival style, in addition to those already mentioned, Wilbur Herbert Burnham and Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock (both with significant windows in the National Cathedral, Washington DC), George C. Ball, (St. Joseph Chapel, College of the Holy Cross), and Margaret Redmond (Trinity Church, Boston).25 Charles J. Connick, however, already discussed as part of the Arts and Crafts movement, was the movement's chief spokesperson, and possibly its most prolific studio.26 The movement extended to an audience in every part of America.27

.jpg)

Clement Heaton,

Apocalypse window, detail

Seated Elders, 1925, Memorial

to Emery Huntington Porter,

Emmanuel Church, Newport.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinMany American studios quickly espoused the Gothic Revival doctrine, encouraged by the patronage of this mode.28 Given the importance of the architect in the selection of stained glass studio, the trend soon became almost universal. The dominance of the Gothic is confirmed by the transition of the German studios to a Gothic Revival style for American commissions, for example in the windows installed between 1927 and 1959 by Mayer and Company in St. Peter's Church, Bowdoin Street, Boston.Clement Heaton, an English-born Swiss national was typical.29 Heaton’s output was prolific, with enormous variation, not only stained glass but also mosaics, interiors, wall painting, and vases. He, like Tiffany was associated with the Parisian enterprise of Siegfried Bing, the Salon of Art Nouveau.30 Some of his work for English patrons is close to that of the Victorian studios in its three-dimensionality. His work in the United States is predominantly Gothic.31 The window of the Apocalypse installed in 1925 in Emmanuel Church, Newport, Rhode Island, for example, is composed of a series of medallions. Blue and red backgrounds dominate the color scheme and realistic space is avoided. The figures are modeled almost exclusively with trace line and “aging” paint appears throughout the window surface.

Princeton University’s Seven Liberal Arts window by the Willet Stained Glass Company

Cram published a great deal, both analyzing past Gothic art and advocating its

Ralph Adams Cram, Proctor Hall,

dedicated 1913, Graduate College,

Princeton University.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinrevival in the 20th century. His most revealing dicta may be found, I believe, in the extraordinarily elaborate and frequently vituperative correspondence he carried on with stained glass studios. The Willet Stained Glass Company, Philadelphia, was employed by Cram, and he had high praise for Willet’s

Willet Studios, Seven

Liberal Arts, initial design,

rejected by architect, 1912,

Proctor Hall, Graduate

College, Princeton

University.

Photo: courtesy of Helene

Weiss of Willet Studios

Willet Studios,

Seven Liberal Arts, 1912,

Proctor Hall, Graduate

College, Princeton

University.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Calvary Church installation in Pittsburgh. 32 He had great problems with the first design submitted by Willet in 1912 for the massive east window of the Seven Liberal Arts for Princeton University's Proctor Hall. 33 [See Appendix] He sharply advised Willet that

"Proctor Hall itself is the richest kind of 15th Century Gothic, the subject of the window is "The Seven Liberal Arts" of Medieval Scholarship, the controlling spirit, therefore in the building and in the window is strongly and conspicuously Christian, and Christian not of the primitive period, nor of the Renaissance, nor of Protestantism, but of the middle ages. . . The design you have sent is purely classical in its feeling and its details . . . You have shown . . . a composition which suggests nothing but Hoffman [sic. German painter Heinrich Hofmann, discussed in the chapter on Memorials] or some other of the Munich school of futilities of the 19th century . . .

Every pictorial element must be eliminated from the window and it must become a great flat decoration; there is no place in it for perspective, and little place for modeling, beyond the strongest and simplest indications of the flesh and drapery; it must be simply a section of translucent wall, richly decorated; the models in my opinion wisest to follow are the windows of the clerestory of Chartres, but the utmost care must be taken to avoid any effect of archaeological copying, any straining after archaism. The whole fundamental principle is the spirit of French 13th and English 14th Centuries, in methods of design, color, composition and leading, expressed through perfectly competent drawing. . . . I am unalterably opposed to all landscape or architectural back-grounds, and of course to the introduction of any classical or architectural detail of any kind whatever.34

Original design rejected

Willet Studios,

cartoon for Grammar and

Dialectic, details of Seven

Liberal Arts, 1912, Proctor

Hall, Graduate College,

Princeton University

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Willet's original design was very much in the tradition of turn-of-the-century poster art such as

Willet Studios, Dialectic and

Grammar of Seven Liberal Arts, 1912,

Proctor Hall, Graduate College,

Princeton University

Photo: Michel M. RaguinAlphonse Mucha's allegorical female types, framed by classicizing architectural details like those of La Farge and Tiffany windows. Cram explicitly admonished Willet to model the Arts after the “great figures in the clerestory of Chartres.”35 Willet's accepted cartoon, although far closer to a medieval spatial system, still retains the sensitivity of drafting traditions of the era. Cram's position was that the Gothic architectural style of the building and the Gothic subject matter of the window by their very nature precluded anything but 13th-century French or 14th-century English models.36 In brief, we see exactly the same arguments as those of Cram's French predecessor in Gothic Revival polemics, Didron, for whom harmony, the concordance of style, was "the first and most important law of beauty." Cram went further, however, for he believed that certain types of worship and their geographic origin wedded them to a specific archaeological style. Catholics (even the Irish) needed Mediterranean-based art, and Anglicans must be presented with churches modeled on English monuments. And in no way could an opalescent window be conducive to worship.

Raymond Pitcairn and the Church of the New Jerusalem, Bryn Athyn

Ralph Adams Cram, Cathedral

Church of the New Jerusalem, exterior

from east, 1913-1919, Bryn Athyn,

Pennsylvania. Photo: author One of Cram's most prestigious commissions was lost because of a conflict concerning the means of achieving an authentic gothic expression. Cram and Ferguson were engaged in 1912 by Raymond Pitcairn for the construction of the Church of the New Jerusalem, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. As the building evolved, Pitcairn, deeply influenced by the writing of Arthur Kingsley Porter on the organic evolution of medieval building practices, insisted on working with a scale model and fostering a close involvement of patron, architect, and contractor. Following Porter's theories, he grouped the craftsworkers on the construction site itself and proceeded to modify the original plan through experimentation with the scale model and full-size plaster models set first within the building. Cram's practice of architecture was modern, relying on drawings and distance from the actual site. There was an obvious clash of personalities and theories of what was a "true" medieval building. The services of Cram and Ferguson were terminated early in 1917. Pitcairn's attitudes also represent the fruitful intersection of the patronage of medieval revival buildings and the collection of medieval works of art so important in Europe in the 19th century. 37

Grisaille

window, south aisle,

Cathedral, Church of

the New Jerusalem,

1920s?, Bryn Athyn,

Pennsylvania.

Photo: author

Guache drawing

for grisaille panels,

archives, Church of the

New Jerusalem,1920s?,

Bryn Athyn,

Pennsylvania.

Photo: author Pitcairn not only supported a number of artist in many aspects of craft, but his collection contained an unparalleled assembly of almost two hundred and fifty works in stained glass, most from France and dating to before 1300. In some measure, the collection was meant to serve as models for Pitcairn’s contemporary workmen. Both figural panels and grisaille found their place. A panel from Salisbury cathedral’s chapter house of about 1280-1290 was clearly the basis for one of the grisaille windows in the nave. the

Grisaille panel, Chapter

House, Salisbury Cathedral,

England, about 1280-1290,

Bryn Athyn Museum, Bryn

Athyn, Pennsylvania.

Photo: Corpus Vitrearum grisaille i

Grisaille window, south

aisle, Cathedral, Church of

the New Jerusalem, 1920s?,

Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

Photo: author .38 A preparatory drawing even gives an indication of how the medieval model was envisioned. The upper segments of the central lancet are highlighted with white gouache over the cream-colored paper and parallel the acquired medieval glass; the artist also reproduced the patterns of curling leaves from the late 13th-century orginal. Lawrence Saint supervised window production at the cathedral from 1917 through 1928 when he left to work at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC.39

In place, the window produces a dynamic range of tonalities, masking any intrusion of image from the exterior, but capturing a brilliancy of illumination within the tall Gothic spaces. The painting clearly attempted to evoke age through shading similar to the application of paint in the Tree of Jesse window installed in 1849 at St. James the Less in Philadelphia. The artists also introduced repair leads to give the appearance of breaks with age, even thought they were not in the 13th-century panel. Replication of fragments of the old was shared. At Salisbury cathedral, a window in the south transept contains four lancets constructed in the 19th century using the same pattern. Fragments of the original grisaille have been set into the largely modern reconstruction.

Collegiate Gothic

Coolidge and Hodgdon, Divinity School,

1926, University Chicago.

Photo: Chris Scott, May 2012The popularity of Gothic Revival architectural styles in America coincided with the growth in size and in prestige of American colleges and universities. Associated with the English precedents of the university complexes of Oxford and Cambridge, the Gothic mode found fertile ground in the American university expansion. Princeton, Yale, Boston College, and the Universities of Chicago and Michigan were some of the many schools engaged in complex building programs in the 1920s.4 Yale's Harkness Tower, chapel, and Sterling Library are Neo-Gothic. As originally designed, the library was a medieval church transformed from its religious cultic function to the "new religion" of scholarship. The transposition of function was guided through the identity of forms. The great entrance at the west portal leads to a great open nave, the side aisles house the card catalogues, the cloister (as traditional, on the south) leads to offices and subsidiary library services. The refectory (on the north arm of the transept) becomes the reading room and the chancel the sacred focus, from which books, not the sacraments are distributed. The glazing of most of Yale's buildings

Owen Bonawit, History of Yale

Library, before dedication of 1931,

Sterling Memorial Library, Yale

University. Photo: Henry Trotter, 2005 was supplied by Owen Bonawit, director of a New York Studio.41 The secular Gothic Revival window system retained more of the Arts and Crafts structure of windows. One observes a great deal of white glass most frequently accented with small medallions in the mode of post-High Gothic glazing such as the grisaille and panel windows of St.-Urbain of Troyes.42 Bonawit produced his medallions from an extremely heterogeneous group of sources having the theme of illustrated books as the common link. Thus Gothic manuscripts, Dürer's engravings, or 19th-century illustrations, were equally welcome. The small size of the panels and their placement within the lattice work of the leading system of white glass achieved a visual coherence within which diversity could operate. Princeton's Graduate Hall is modeled after a Gothic secular building and the windows' forms and themes, the quest for knowledge and truth in The Seven Liberal Arts and The Holy Grail [See Appendices] are consonant with the restructuring of medieval religion into modern scholarship.

Boston College: transformation from the Renaissance to the Gothic

.jpg)

Arthur Gilman, Church of the

Immaculate Conception, Interior, 1861,

Boston, Mass, stereograph, Bierstadt

Brothers (photographer), Boston Public

Library, Print Department.

Photo: Uploaded from http://flickr.comBoston College's plans during relocation from Boston's South End to its present Chestnut Hill Campus exemplify the power of the European model. The College's original buildings in Boston were based on Renaissance forms, eloquently demonstrated by the form of the old College Chapel, repurposed as the Church of the Immaculate Conception, closed in 2007. The Jesuit order was founded by Ignatius Loyola in 1533 and became a major force in the Catholic Counter Reformation. The Jesuits prided themselves on representing a rigorous education associated with Renaissance thought. In 1858 Patrick C. Keely designed the frame of the building following Renaissance stylistic principles and Arthur Gilman, the architect of the Arlington Street Church in Boston, designed the elaborate and eloquent interior, completed in 1861.43 In 1899 it was cited by with justified pride by the archdiocese as "one of the finest church

Earl Sanborn,

Shakespeare Windows, 1924-28,

main staircase, Bapst Library,

Boston College. Photo: author edifices in New England."44 By the first quarter of the 20th century, however, the Jesuits apparently felt independent of such models to adopt the generic revival mode of Gothic, as

Maginnis and Walsh, Gargan

Hall, Bapst Library, 1924-28,

Boston College. Photo: Jeffery Howe opposed to personally coded Renaissance associations. That a predominantly Irish-Catholic patron could select English university models is an indication of how powerful the collegiate Gothic style had become for Americans.45

The Boston architectural firm of Maginnis and Walsh was commissioned to design a cluster of twenty-two buildings in the "English collegiate Gothic style to occupy the new hilltop site on the Newton border."46 The Bapst Library, 1924-28, was the fourth building completed, and admittedly the one most articulate in its period style. Over the library's main entrance is a tympanum bearing the image of Virgin Mary as the Throne of Wisdom, a theme borrowed from the 12th-century portal sculpture of the cathedrals of Chartres and Paris. The central reading room, Gargan Hall, is a wide aisled structure under a hammer-

Earl Sanborn,

Michelangelo, 1924-28, reading

room, Fine Arts alcove, Bapst

Library, Boston College.

Photo: authorbeam roof. The glass was provided by Earl Sanborn of Boston, and thematically linked to Jesuit education.47 The fourteen study alcoves between the aisle columns function in the place of ecclesiastical side chapels. Their windows depict individuals and events linked to the major courses of study in Jesuit universities and colleges, such as Philosophy, Fine Arts, Political Science, Law, and Medicine. In other areas the windows portray characters from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Shakespearean creations, or themes from Irish mythology, among other historical and literary topics. Boston College's glass is more consistently of the Gothic Revival mode, for Sanborn, who had worked earlier in the Connick studio, produced images based on early medieval prototypes, rigorously eschewing perspective and three dimensional modeling.

Draftsmanship and vision, then and now

What distinguished the Gothic Revival from the Gothic itself? One does not now so easily confuse Mrs. Gardner's Soissons panels with Heaton’s windows in Newport. The explanation may perhaps be lurking in Cram's revealing instructions to Willet. "Finally it should be clearly understood that in everything I say I am not suggesting in any way shape, or manner that your design of the glass should be archaic. The principles of the XIIth and XIIIth centuries are right in design, composition, colour combination and decorative effects; the drawing is, of course, archaic and crude, this no one wants, what they all do expect, however, and what I think should alone pass for good glass today, is an expression through adequate and effective drawing of the ideals and methods of the French and English glass."48

It is the draftsmanship, above all, that distinguishes even the best-designed Gothic Revival window from its medieval model. The modern artist was self-consciously aware that he or she was rejecting three-dimensional academic modeling to create a decorative language believed to be unique to the art of stained glass. It was this self-consciousness of the abstract and graphic nature of stained glass painting that was the strength and also the curse of the movement. At their best, the artists were truly excited by the play of the dark lines of the lead systems coupled with the dramatic manipulation of trace paint held within a matrix of shifting colors. What was created was exactly that "section of translucent wall, richly decorated" praised by Cram. The tendencies in American art during the teens and twenties towards greater abstraction and bold contrasts, and the subsequent Art Deco movement, as well, corresponded to the emphasis on graphic intensity prized by the Gothic revival.

Access to models before the internet or quality color photography

One of the most cherished books of this era was Hugh Arnold and Lawrence Saint's Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France.49 The text is evocative, if restricted, and it is significant that the title page lists the illustrator first. Saint, discussed early for his work with Raymond Pitcairn, provided fifty water color illustrations of what came to be the "canon" of great windows, interestingly enough the same canon most often cited by art historians of the succeeding generation, Le Mans, Poitiers, Canterbury, Chartres, York, through Rouen and Fairford of the 15th century. The overview of great monuments excluded German work, Italian or Spanish windows, or any of the vast programs of the English, French, and Lowlands Renaissance so frequently praised by the scholars of the preceding century.

Printed sources and the role of restorer’s publications of Gothic models

Reynolds,

Francis & Rohnstock,

St. Swithin, 1931,

Shove Memorial

Chapel, Colorado

College, Colorado

Springs. After

Timothy Fuller, ed.,

This Glorious and

Transcendant Place,

Colorado Springs,

1981.

Cathedral of Le Mans,

nave, Ascension, detail,

1140-1145. After Eugène Hucher,

Calques des vitraux peints de la

cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1864.Printed sources, including accurate tracings of medieval windows published by 19th-century restorers provided the 20th-century studio with models for styles and iconography. For

Cathedral of Le Mans, west

façade, Life of St. Julien, detail, 1150’s.

After Eugène Hucher, Calques des

vitraux peints de la cathédrale du

Mans, Paris, 1864.example, the Boston studio of Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock produced windows in 1931 for the Shove Memorial Chapel, Colorado College portraying early English saints. They were inspired by the 12th-century windows of the cathedral of Le Mans to complement the "Norman Romanesque" architecture of the chapel.50 Eugène Hucher had restored windows of the cathedral and published the tracings made from the windows.51 Hucher headed a large studio that had exported glass to the United States, as noted for the University of Notre Dame. The firm reproduced the same insistent blue and red contrast and silhouetting of figures against a plain, undifferentiated

Reynolds, Francis &

Rohnstock Christ Blessing

the Children, 1946, Central

Congregational Church,

Worcester, Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin background.

Reynolds, Francis &

Rohnstock Christ Blessing

the Children, 1924,

Hunnewell Chapel,

Arlington Street Church,

Boston. Photo: author The alternation of figural medallion and decorative border repeats the even balance of the medieval relationship. Even the particular style of the figures, with vivid gestures and swaying draperies, often shown with heads tilted back emphasizing their dark curly hair, were reproduced in the Colorado commission.

Several important windows by the firm grace the landmark building of Arlington Street Church, Boston (whose Tiffany program extended from 1898 through 1929). Gothic Revival was favored for newer work and in 1924 and 1927 Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock installed windows in the Sunday School Room (now the Hunnewell Chapel). The image of Christ Blessing the Children of 1924 would reappear in a window for Central Congregational Church, Worcester in 1946. Indeed, a comparison of the two works reminds us of the close elision between the Arts and Grafts movement and the Gothic revival. The firm also produced two massive windows for Princeton University Chapel. Multi-light windows celebrating martyrs (north transept) and teachers (south transept) grace the Cram-designed building.

Without museums: the essential publications of Viollet-le-Duc, Westlake, and Connick

Head from the

Cathedral of Notre

Dame, Paris,

possessed by

Viollet-le-Duc,

attributed to the

1180s. After Charles

J. Connick, Adventures

in Light and Color

(1937), p. 47

(Dictionnaire, p. 419). As interest in windows inspired by past styles grew, a wider number of publications on the history of stained glass appeared. Many of the studios had magnificent libraries, not only books on

Border from Tree of

Jesse window, 1140s, St.

Denis. After Charles J.

Connick, Adventures in

Light and Color (1937),

p. 39 (Dictionnaire, p. 391).stained glass, but on costume, decorative arts, architecture, and religion.52 Reynolds, Francis, & Rohnstock's windows for the Shove Memorial Chapel for Colorado College based on the Hucher’s publication have already been mentioned. Westlake's four volume History of Design in Stained Glass of 1881-1894 was an essential reference in American studios. Translations of Viollet-le-Duc's section Vitrail (on stained glass) from his Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française of 1869 were available. Indeed, many of the illustrations that Charles Connick used for his own work, Adventures in Light and Color of 1937 were borrowed from Westlake and Viollet-le-Duc. Often the same illustration after Vitrail appears in the Westlake's and again in Connick's book. These publications operated in the vacuum of real-life experience.

Although the Metropolitan Museum and Cloisters, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art presently furnish the viewer with a substantial collection of medieval and Renaissance windows, acquisitions only began in the 1920s. Otto Heinigke, a stained glass artist cited earlier in the discussion of Arts and Crafts windows, lamented the situation. He had seen collections in Europe, and commented that neither the Metropolitan Museum nor the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had a single work on display.53 The wide use of illustrated books, such as those authored by Westlake, Viollet-le-Duc, or Winston meant that the American studio was confronted first with the modern rendering of a window, often as a wood engraving, not the medieval window itself. Thus the image of the Gothic window was already one filtered through a 19th-century sensibility. Heinigke addressed this disparity, as he was familiar with the interactive effects of medieval windows on the site. He wrote of colors modulating the regularity of lead lines. "This peculiarity will give an almost straight line much play as it passes between the various colors: hence the lithographic reproductions of exact lines of old glass always look repellently angular when compared to old windows in place."54

Linear emphasis in wood engraving illustrations

Seated King, detail

from Tree of Jesse window,

1140s, St.-Denis. After

Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire

raisonné de l’architecture

française (1869), p. 388.Both the method of reproduction and the image itself in these early publications are constrained. Modulation is absent in the engraving. All marks are either

Flight into Egypt, from Infancy

window, 1140s, St.-Denis, Glencairn

Museum, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

Photo: authorblack or white, a

Flight into Egypt, detail, 1140s,

St.-Denis, Glencairn Museum, Bryn

Athyn, Pennsylvania. Photo: author phenomenon of reproduction that encouraged the sharp linear systems of the modern work. Viollet-le-Duc's highly schematic rendering of one of the seated kings of the Jesse Tree window of Chartres, so often cited in stained glass literature, is eloquently linear.55 This material was eagerly welcomed by scholar and craftsperson, but interpretation demanded a close knowledge of the medieval object itself. The Flight to Egypt panel from the St.-Denis Infancy window, especially in the donkey’s main, reveals varying intensities of paint as had been cited in Theophilus' 12th-century treatise On Divers Arts. English translations of the seminal work were available, and references to Theophilus’s description of the medieval application of three layers of washes were made in the literature, especially by Connick.56 However often the painting nuances might be cited, they

Diagram of color

radiation. After Charles J.

Connick, Adventures in Light

and Color (1937), p. 30

(Dictionnaire, p. 389).were impossible to reproduce in the book illustrations.

Violet-le Duc’s theories of color

The Gothic Revival's grounding in mid-19th century French theory is nowhere more evident than in Connick's affirmation of Viollet-le-Duc's thesis of the radiance of blue in medieval windows. Connick reproduced, in a color plate and black and white, Violet-le-Duc's diagrams explaining the radiance of blue glass turning the junctures of red and blue to purple without the introduction of a grisaille paint on clear fillets separating the colors. This phenomenon very probably would not have been so apparent to Connick, if indeed it truly was, without the authority of the French author as a reference. It suggests that Connick accepted the 19th-century "science" and design principles as self-evident. The artist’s own aesthetic drive, however, enabled the firm to produce windows deeply relevant to the 20th-century, based on a sensitive perception of the value of paint application to modulate light and color.

The synergy among museum, collector, and studio

Seated Monarch,

probably early 20th

century, Quarterly of the

Los Angeles County

Museum of Art, vol. 4,

nos. 3, 4 (1945) front coverGothic Revival concepts were to exert a profound influence on collecting and connoisseurship.

Margaret Redmond, Apostles windows,

Sts. James and Matthias; Sts. Thomas and

Bartholomew, 1920, nave side aisles, Trinity

Church, Boston. Photo: author French High Gothic stained glass became the most prized element in museum collections and comprised the canon of university instruction in medieval art. In 1945 the Los Angeles County Museum published an assessment of its medieval stained glass recently bequeathed by William Randolph Hearst. The most important panel, according to the length of description and prominence as cover illustration, was a "French 13th century" panel Christ before a Seated Monarch. "The earliest piece of glass in the Hearst collection, a vibrantly colored medallion, evidently was once part of a larger window. . . . This medallion is of French workmanship and dates from the thirteenth century, the greatest period of stained glass manufacture. In it can be seen the stiff, formal, and hieratic composition, the jeweled patterns, and exuberance of color characteristic of thirteenth century glass. Despite technical limitations, thirteenth century glass has never been equaled in quality of design or beauty of color. The metallic ores used by the medieval craftsman to color the glass were crude and impure but nonetheless produced amazing varieties of color. The glass, although capable of being made only in small pieces, none larger than the palm of a man's hand, gives by this very fact a jewel-like quality to the windows. The uneven and varying thicknesses of the small pieces of glass breaks the light coming through the windows into irregular and scintillating refractions of color. The leads which joined the pieces of glass were well organized, adjusted to the article of window design, and formed an integral part of it. In later centuries when the techniques of glass making were improved, many of these assets of medieval glass, imposed actually by technical limitations, vanished. By the sixteenth century, when glass could be made in large sheets, when the entire design could be painted with enamel colors onto the glass, the mosaic technique of the medieval widows was entirely supplanted and the true art of stained glass became extinct."57

Unfortunately, the panel described with such fervor is a fake.

In retrospect, the fake is a highly obvious one, especially in comparison with the window from Soissons now in the Gardner Museum, or a similar seated figures from the window of the Life of St. Nicholas at Chartres cathedral, details of which Connick reproduced in Adventures in Light and Color. It is instructive, however, to ask how the now "obvious" illogical folds, awkward composition, and disjunctive color harmonies could have been accepted as authentic. In the discussion we might do well to realize that the 20th-century artist had been inspired to replicate repair leads and color shifts resulting from restorations. One sees such effects, as well as the stress on surface line, in the Apostles by Margaret Redmond in the nave aisles of Trinity Church, Boston.58

Evaluation of the authentic

Stained glass is difficult to expertise. A single panel may exhibit a wide variety of problems of authenticity. A segment may have been entirely replaced by a modern copy; the transparency of the material allowed restorers to place cracked or effaced pieces on a light board and to model new portions by tracing the lines of the original piece. This creates a situation where the copy may be so close to the original that only a meticulous analysis of glass texture, paint application, and color may help identify the replacement. Other interpolations may be well-designed infills to replace missing sections having occurred over a series of historic restorations. Another segment of glass may have suffered paint loss, and was restored with heavy modern overpainting. In addition, works may recombine segments of two or more similar windows to achieve a very credible appearance of a whole.59

The counterfeit is our ever present challenge, and yet it may be one of our most valuable learning tools. Max J. Friedländer characterized the appeal of the fake in a graceful admission in his 1930 book, Genuine and Counterfeit.60"No matter how successful the art scholar may have labored to enter into the manner of the past, no matter how sincere and deep his love for the old masters, the gulf of time can never be entirely bridged. Something harshly foreign, not agreeable to our taste remains operative in the world of forms created by our ancestors. This, however, is seldom conceded. The forgery, a contemptible thing when once seen through, possesses before its disclosure a double charm; it is supposedly the work of a great and famous old master, and it is also the product of a contemporary, whose taste is akin to our own."61 The false panel has many of the qualities that we expect to see in an old work of art and articulated in precisely the language that we have used to characterize the coveted past. In short, the Hearst panel looked a great deal like many Gothic Revival windows.

To deconstruct the fake is to understand our prejudices. The published description reveals what kind of artistic values seemed embodied by Christ before a Seated Monarch. The curator begins an evaluation with the bias that stained

Jesse Tree, detail

of donor Celse Morin

presented by his patron,

St. Celse, about 1515,

Cathedral of Autun.

Photo: Marilyn Beavenglass is a medium of great medieval expression. The difference between the modern draftsmanship and design, not the manipulation of artistic issues in a medieval context, became the most visibly distinguishable, and valued, quality of the panel. Fragmentation, reliance on a mosaic of colors, and "stiff" draftsmanship, become accepted authentic Gothic features, and the panel's deliberately faked awkwardness thus confirmed its medieval origins.62

The perceived disjunction of “true principles” in stained glass from the progress of period styles

Unlike Gothic Revival glass painters who employed modern products, forgers invariably reused elements of old windows. After removing the original paint by an acid bath, they could create a new medievalizing element that appropriated the authenticity of the substrata of the medieval color. The absolute conviction that this was a craft-bound art whose expression was determined by the nature of materials (the oft-cited true principles of the art) was behind the forger's success. We return to Charles J. Connick, who arguably spoke for others, in his antipathy for later medieval work. In the midst of his lavish, and for many, justifiable praise for the 12th-century Jesse Tree and St. Denis, he castigates the early 16th-century Jesse Tree of the cathedral of Autun.63 For this artist, the window seemed “As restless and literal-minded as an American advertisement.”64

Cathedral of Chartres, north nave

aisle, detail of St. Nicholas window,

1205-1215. Photo: Michel M. Raguin The history of stained glass as a separate medium, disassociated from the general continuity of styles and historical context was accepted by the Los Angeles County Museum curator: "In the Romanesque and early Gothic period, glass painting and tapestry weaving are forms of art

Illuminated

manuscript page, Paris,

The Tree of Jesse, The

Annunciation, The Nativity,

and The Annunciation to

the Shepherds, from the

Wenceslaus Psalter,

1250-1260, J. Paul Getty

Museum, Los Angles,

Ms. Ludwig VIII 4, fol. 22v.

Photo: courtesy , J. Paul

Getty Museumcompletely distinct from painting. When glass painting and tapestry become pictures in the same sense that a painting is a picture, they lose their identity as works of art."65 By definition, then, stained glass is simply stained glass, not one of the many material choices that carry figural or architectural decoration throughout what we have come to identify as the history of art. That one could hold such a strange position, when a quick glance at 13th-century manuscripts would reveal painterly choices identical to those in windows, I would argue, stems from the modern context of the disjunction of the Gothic Revival stained glass from other contemporaneous painting styles. The later work by Connick, Burnham, or Willet in the Gothic Revival mode is unlike the works exhibited in 20th -century galleries, and was unknown as an aspect of instruction in schools of fine art. Subliminally, the acceptance of this modern disjunction, necessitated by the "true principles" of the medium, allowed many usually astute arts professionals to see stained glass as a separate and unchanging field.

Medieval art admired

The early 20th century did see a new attitude toward the nature of medieval art; the panels from Soissons are some of the finest examples of French High Gothic glass painting in America. Adams believed the window came from the abbey church of St.-Denis, not a surprising assumption given his knowledge of the confusion attendant on the dismantling of the abbey's windows in the early 19th century.66 Only a year earlier Adams had published his Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres whose second edition of 1913 included an introduction by Cram. Adams is praised explicitly for perceiving the unity of art, philosophy, politics, economics, and religion in "the greatest epoch of Christian civilization."67 The Gothic, to Adams, Cram, and an entire generation of patrons and followers, provided a true revival of the principles of Christianity in a modern world, a world frightened by its own multiplicity and longing for a "unity" so fervently believed to have animated the long-passed era.

The challenge of Gothic Revival imagery

The imagery selected by the Gothic Revival contrasts markedly with that of the 19th-century, whether traditional European or American opalescent. The Gothic design most often favored small medallions set against mosaic grounds similar to those in the glass from Chartres, the Sainte-Chapelle or other High Gothic examples such as the Soissons window now in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Connick, Redmond, Burnham, and the rest multiplied these small figurative scenes in lengthy narratives, often very difficult to identify without an inscription. As the Gothic Revivalists strove to imitate the forms of the 13th century, it seems that they imitated what they perceived to be the arcane imagery of the time. The self-conscious nature of the abstract two-dimensional forms is matched by a deliberately esoteric program. The program of the Princeton University Chapel [Appendix], is a site-specific compendium of moral lessons developed through biblical, historical, and literary references. It is decipherable with time and effort, but it does not convey its themes immediately to the casual observer.68

Writing out the text

Connick's published descriptions of his windows, often part of the congregation's dedication or memorial brochures, reveal that he expected to instruct in words as well as in image. It was accepted the he was creating art for a literate public who would have the text in front of them as they viewed his product. He defined for them an "objective" symbolism of colors:

Red: Color of divine love, courage, sacrifice, passionate devotion and royalty

Blue: Heavenly truth, loyalty, eternity

Violet: Humility and suffering

Green: Victory, hope, joy, youth

Gold: Achievement, spiritual riches, wisdom, learning

White: Purity, celestial power, serenity, and light 69

His own description of a window of the three Theological Virtues shows the application of these ideas.70 He explains that Faith is robed in blue, gold, and violet, and Hope in green, gold and violet. St. Elizabeth of Hungary, representing the virtue of Charity, wears a scarlet robe "which symbolizes Heavenly Love." Although color symbolism may have been somewhat standardized in western Europe for liturgical ceremonies since Innocent III's treatise in the early 13th century, these rules rarely impacted the visual arts. In the Middle Ages, there were no universal rules, however much Neale and Webb of the Cambridge Camden Society in the 19th- century or Cram and Connick in the 20th-century perceived them.71 Still, a generation of churchgoers accustomed to the sequence of liturgical colors for altar cloths and vestments for the different feasts of the Christian calendar may have found these concepts somewhat more familiar than the contemporary viewer, but perhaps not immediately.

Princeton University Chapel and Connick’s windows in the Milbank Choir

Ralph Adam Cram,

University Chapel, 1925-1928,

Princeton University,

Photo: Andreas PraefckeConnick's work in the Princeton chapel eloquently sums up the power and the challenge of the Gothic inspired systems.72 The old Romanesque style building built by Richard Morris Hunt had been destroyed in a fire in 1920. Dedicated in 1928, the new chapel followed the program of Collegiate Gothic that had become the university's standard since the construction of the Pyne Library in 1896. The chapel and its decorative programs are the product of a collaboration between Professor Albert Mathias Friend, the prominent medievalist, and the architect Ralph Adams Cram. Cram at that time held the position of supervising architect of the University and only ten years earlier has completed the Graduate Center and Proctor Hall, where Willet and Connick windows had been installed.

The decorative programs of the building were complex and site-specific. A single example from an extremely rich field may suffice to explain the simultaneity of the medieval and non-medieval character of the chapel. The seven virtues sculpted above the doorway in the north aisle are not those of the High Middle Ages, traditionally a division between the theological virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity, and the cardinal (or natural virtues) of Prudence, Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude. Princeton's selection, presented as "the" seven virtues, are evocative but not traditional: Humility (dove), Charity (horn of plenty), Chastity (unicorn), Patience (lamb), Temperance (centaur), Mercy (rose), and Diligence (bee). The unicorn traditionally places its head on the lap of a virgin, the only way it can be captured, and centaurs are known in Greek mythology for having become inebriated and behaving dishonorably at the wedding feast of the Lapiths, a theme depicted on the metopes of the Parthenon. The corresponding symbols of the vices show the same inventive and eclectic attitudes, playing to the 20th-century imagination of an arcane but fascinating medieval source. The imagery in the glass is equally 20th-century in nature.73

Windows of a modern synthesis

Charles J. Connick, Pilgrim’s

Progress window, Milbank Choir,

University Chapel, Princeton University.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinAlthough added later, the windows were site-specific and planned under Friend's

Charles J. Connick,

Pilgrim’s Progress window,

Milbank Choir, University

Chapel, Princeton University.

Photo: Boston Public Library direction. [See Appendix] Products of number of studios and artists working in the Gothic style, they show a cohesive stylistic integrity.74 Connick's windows of the Milbank choir were among the earliest installed and most impressive. 75

Charles J. Connick, Morte

d’Arthur window, Milbank Choir,

University Chapel, Princeton University.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin They presented the university with images reflecting the Christian tradition in biblical literature and the canon of great books associated with a Christian education. Pilgrim's Progress by Bunyon is one of the most vigorous, shaping the story in bold dialectic of angles. The compositions, to Connick's great credit, interweave the text and images, creating strong intersecting linear patterns, very similar to the abstract graphics of the then current Art Deco style. The painting frequently gravitates to a sgraffito technique, the application of paint and then the scratching out of the design to reveal the color of the glass. This mode had resurfaced with the Arts and Crafts/Art Nouveau artists, especially for ceramics. The small figures surrounding the author and his protagonist are visibly energized through angular line.

The result is a visually exciting but "bookish" depiction of literature though episodic details and labeling inscriptions. The pattern is compelling; the legibility problematic. At Princeton, we see the best of the Gothic Revival efforts, the bridge between the Arts and Crafts and later medievalizing glazing, and the American university's powerful appropriation of the authority of the past through architectural form.

A long experience

Charles J. Connick

Studio, Crucifixion, 1956,

Cathedral Church of Saint

Mark, Episcopal, Salt Lake City.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin The viability of the Gothic was long lived. A window depicting the Crucifixion, installed in 1956 in the Cathedral Church of Saint Mark, Episcopal, Salt Lake City proclaims much of the strength of this mode. Charles J. Connick had died in 1945, twelve years earlier. The studio, however, was collaborative, and continued creative reinterpretation. The image is eminently legible, the figures accessible but removed to a sphere of contemplative distance. The “aging paint” application has been transformed into a dynamic graphic frequently visible as a pattern that modifies the light passing through the blue and red background segments. If still referencing the memory of repair leads, the cames form a coherent linear overlay. The division of the Christ’s flesh areas through diagonal lines and contrasting tones serves to move the viewer's eyes up from the feet, across the chest and out to the extended arms. There is no question that this long and complex era of Gothic inspiration extended productively for over a half century.

REFERENCES

![]()

1. ^ John Gilbert Lloyd, Stained Glass in America (Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, 1960) and Connick 1937. Most of Connick's important commissions are discussed and often illustrated.

2. ^ It is not possible here to address the career of this complex personality. The literature on Pugin is substantial. See most recently the 443 page study by Stanley A. Shepherd, The Stained Glass of A.W.N. Pugin (Reading: Spire Books, 2009), and Paul Atterbury and Clive Wainwright, eds., Pugin: A Gothic Passion [exh.cat.Vicotria & Albert Museum] (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994). See also Raguin 2003, chapters 7 and 8 for the context of the European revival of stained glass in the 19th century.

3. ^ Margaret Stavridi, Master of Glass. Charles Eamer Kempe 1837-1907 (London, 1988); Quirk 1993, 118-121.

4. ^ Cram will appear frequently throughout this chapter. A contemporary response to his influence is seen in the many tributes to him at his death by stained glass artists and architects in Stained Glass 37/4 (1942), esp. 105, by Charles D. Maginnis of Maginnis and Walsh, the architectural firm. "Cram will be identified with the influence which lifted ecclesiastical architecture from comparative illiteracy to its present respectability. He lived to witness the close of an epoch. A new philosophy with the force of revolution has now arisen to protest the principle of tradition, and the end may have come to the Gothic episode." For evaluation of his influence see Muccigrosso 1979. Cram's architectural work in the Boston area has been studied by Douglass Shand-Tucci, The Gothic Churches of Dorchester (Boston, 1972, repr. 1974), Shand-Tucci 1973, Idem., Church Building in Boston, 1720-1970 (Boston, 1974); Idem., Ralph Adams Cram: Life and Architecture vol. 1, Boston Bohemia (Amherst, Massachusetts; University of Massachusetts Press, 1995) and Idem., Ralph Adams Cram: An Architects Four Quests, Medieval, Modernist, American, Ecumenical (Amherst, Massachusetts; University of Massachusetts Press, 2005); Richard Guy Wilson, "Ralph Adams Cram: Dreamer of the Medieval," Medievalism in American Culture, Bernard Rosenthal and Paul E. Szarmarch, eds. (Binghamton, New York, 1989), 193-214. Peter Fergusson’s study, “Medieval Architecture and Scholarship in America: 1900-1940: Ralph Adams Cram and Kenneth John Conant,” The Architectural Historian in America, Studies in the History of Art, vol. 35 (Center for the Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers 19, Washington, D.C., 1990), pp. 127-42. Anthony Allen, The Architecure of Ralph Adams Cram and his Office (New York: W. W. Norton, 2007).

5. ^ Coleman 1893a, pp. 264-85. The essay is illustrated with numerous line drawings, most from of the 12th-and 13th-century windows of Chartres. It is interesting that he accepts, even recommends, plating to soften the harshness of the lead line (p. 285).

6. ^ Adolphe Napoléon Didron (Didron l'aîné), editor of the Annales archéologiques and founder of the Didron stained glass studio. Edmond Lévy, author of Histoire de la peinture sur verre en Europe et particulièrement en Belgique ( Brussels 1860). See Virginia Raguin, “Revivals, Revivalists, and Architectural Stained Glass,” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 49 (1990): 110-139.

7. ^ Coleman 1893a, p. 268.

8. ^ Coleman 1893a, p. 282.

9. ^ Coleman 1893a, p. 282.

10. ^ I am grateful to the late Jane Hayward, who pioneered a concerted effort to study of post-medieval glass in the United States, with whom I first saw Emmanuel Church. The church has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1996. John Nicholas Brown and Harold Brown were members of a prominent Rhode Island family that was involved in business, education, and collecting. In 1804 the institution founded as Rhode Island College was renamed Brown University to reflect this long history of benefactors. John died in 1900 of typhoid at the age of 39 and his older brother died ten days later. John had devoted himself to expanding the collection of books on Americana begun by his father John Carter Brown; it was given to Brown University. John’s window, Natalia Bayard Brown, donated the funds to build Emmanuel Church in his memory. See Walter C. Bronson The History of Brown University, 1764–1914 (Providence, 1914).

11. ^ In 1905 Cram would commission Goodhue to design the first window installed in All Saints Brookline, Massachusetts.

12. ^ Albert Franz Cochrane, "The Genius of Wright Goodhue," Boston Evening Transcript (August 22, 1931), 8-9. Detail of Apostles from the Creed window and St. Mary of Celophas, from the choir clerestory; Angels from Mercersburg Chapel.

13. ^ I am grateful for the American Glass Guild’s 2012 Conference held in Pittsburgh and the expertise of Albert M. Tannler, Historical Collections Director, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, who lead tours of many ecclesiastic and domestic sites. Tannler has researched the buildings in the Pittsburgh area as well as stained glass, especially windows associated with Charles J. Connick. See Charles J. Connick: His Education and His Windows in and near Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation; 2008) and William Willet in Pittsburgh: A Research Compendium (Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation; 2005). Many important Catholic buildings were constructed in the first half of the 20th century, and it is tempting to believe that the clerical patrons were deeply involved with the iconographic programs. That of St. James is remarkably profound, with multiple references of theological themes such as the Creed whose articles of belief are carried by the twelve apostles, the Tree of Jesse depicting the lineage of Christ, or the choir clerestory showing the witnesses on Golgotha complementing the Venetian marble mosaic of the altar showing the eclipse of the sun during the Crucifixion. Mary Cleophas is mentioned in John 19:25 as one of the women present at the Crucifixion; she is often identified as the mother of the Apostle James the Less.

14. ^ Rose of chancel and transepts in Church of the Sacred Heart, Jersey City, New Jersey, apse window of Mercersburg Academy Chapel, Mercersberg, Pennsylvania (communication from Jay L. Quinn, Alumni Secretary), Church of the Holy Rosary, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, south clerestory window of Emmanuel Church, Newport, Rhode Island, windows of the crossing and choir clerestory, Princeton University Chapel (Stillwell 1971, pp. 36-9). Significantly, Cram wrote a moving tribute to the artist. See Ralph Adams Cram, "Personal Recollections of Harry Wright Goodhue," Stained Glass 27 (1932), 263-73, which includes discussion and illustrations of other commissions as well.

15. ^ See Madeline H. Caviness and Jane Hayward, "Introduction," in Corpus Vitrearum Checklist III, pp. 13-14.

16. ^ Caviness, Beaven, and Pastan 1983, pp. 6-25.

17. ^ Catherina Pirina, "Stained Glass from Milan Cathedral in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum," Fenway Court (1983), 26-37. The Soissons window is set within the chapel, now functioning as part of the flow of spaces continuing from the Long Gallery. In 1901, Fr. Frisby from the Church of the Advent consecrated the space with a private mass on Christmas Eve. Isabella Gardner continued the tradition and held a mass on Christmas Eve in the Long Gallery Chapel every year. Today the chapel is the site of a requiem Mass said on Isabella Gardner’s birthday, April 14.

18. ^ Mark A. Wuonola, Church of the Advent, Boston: A Guidebook (Boston, 1975), pp. 17-20, 38, 45. Clayton & Bell, London, appear to have been favored by the architect John H. Sturgis who designed the Church of the Advent in a High Victorian Gothic mode. He emulated the work of William Butterfield, in particular All Saints' Margaret Street, London, often cited as pre-eminent design in this style. In 1897, a Tree of Jesse for the west window was commissioned from Kempe, also of London, a favorite studio of the architect Henry Vaughan. Isabella Stewart Gardner does not appear to have influenced the selection of windows. She was deeply involved in the church, however, funding the elaborately carved upper reredos in 1891 (p. 36). I am grateful for conversations with Mrs. Betty Morris, librarian, for insights concerning church patronage.

19. ^ The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, vol. 2 (Boston, 1854), 397-98.

20. ^ See Maureen Meister, Arts and Crafts Architecture: History and Heritage in New England (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2014) who sets Cram in the context of the promotion of design based on historical precedent and ornament but blending Arts and Crafts values with Progressive Era idealism. Seasonwein 2012, has researched primary documents of the time to show Cram relationships with both the patrons and the glass makers at Princeton University. The narrowness of Cram's range of Gothic models, his belief that the past was not really dead, and his fervent religious faith distinguished him from his one-time partner Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869-1924). Goodhue believed that architecture could be spiritual without being "religious", and his wide range of sources and interest in site-specific conditions are evident in the range of his buildings. See for example, St. Vincent Ferrer, New York City, in a Gothic mode, the California Institute of Technology in a Spanish Colonial mode, and Goodhue's use of the designs of the previous building and Italian Romanesque sources for the new St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York City. See Smith 1988 for a comprehensive treatment of stylistic sources and patronage of St. Bartholomew's.

21. ^ I am indebted to the late Kermit S. Champa, Brown University, for his probing insights on this issue.

22. ^ For recent expressions in flat (windows) and hot glass, see exhibition and acquisitions by the Corning Museum of Glass and journals such as Glass (formerly New Work) [New York Experimental Glass Workshop].

23. ^ Harry Eldredge Goodhue, "Stained Glass," Handicraft 2/4 (1903), 82. See on p. 76, illustration of Brown memorial window in Emmanuel Church Newport, Rhode Island.

24. ^ Sarah (de St. P.) Whitman, "Stained Glass," Handicraft 2/6 (1903), 117-31.

25. ^ See recently for Burnham, Albert M. Tannler, “The ‘Autobiography’ of Wilbur Herbert Burnham, Sr.,” The Journal of Stained Glass, vol. 37 (2009): 94-103. See also Norman Temme, "The Burnhams: A Story of Outstanding Achievement," Stained Glass 77/4 (1982-83): 366-370. For a personal statement very similar those by Connick and Lawrence Saint see Wilbur Herbert Burnham (Artist - Craftsman), "Stained Glass Construction and Details," Architectural Forum, vol. 38 (1924), 1-10. The Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament, Washington D.C., with windows by Wilbur Burnham Sr. installed in the 1920s was the subject of a 1984 study by the church's 75th anniversary window committee, chaired by David S. Orem. I am grateful to Mr. Orem for sharing the results of this study.

26. ^ See Connick 1937, esp. pp. 349-77, 400-404, 408, for information on these studios and location of many of their works.

27. ^ See, for example, St. John's in St. Paul, Minnesota, see Robert Orr Baker, A Centennial History of the Parish of St. John the Evangelist, St. Paul (St. Paul, Minnesota). A sampling of Gothic Revival work by Wilbur H. Burnham, Earl Edward Sanborn, Joseph G. Reynolds, Lawrence B. Saint and others is found in Jewels of Light. The Stained Glass and Mosaics of Washington Cathedral, Nancy S. Montgomery and Marcia P. Johnson, eds. (Washington, D.C., 1984).

28. ^ For example, see Henry Keck studio of Syracuse, New York, whose change of style in the 1920s shows Gothic Revival influence. Reed 1985.

30. ^ A marvelous series of opalescent landscape windows of the seasons produced in 1903 is found at the Church of Saint-Aubin, (canton of Neuchatel), Ibid, pp. 26-27. For specifics on Bing and Heaton see 185-193 for the essay by Gabriel Weisberg.

31. ^ Ibid., pp. 58-75. Installations are geographically dispersed and include Trinity Cathedral, Cleveland, Ohio; Church of the Blessed Sacrament and Church of St. Rose of Lima, New York New York; St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, Charleston South Carolina; and All Souls Episcopal Church, Washington DC.

32. ^ Seasonwein 2012, pp. 81-100, presents an in-depth study of the commission of the Seven Liberal Arts window, illuminating the tension among William Willet and Charles J. Connick, artists in glass, Cram, the architect, and Andrew Fleming West, Dean of the Graduate school. She notes the strong support evidence by Cram for Connick, even to the architect’s soliciting a new design from Connick after Willet’s had been submitted and was under revision. West, however, supported Willet. The exhibition at Princeton in 2012 included Willet’s watercolor for the original proposal.

33. ^ Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson, Architects,” Architectural Record 35/1 (1914) $$page, and Montgomery Schuyler, “Architecture of American Colleges, III, Princeton,” Architectural Record 27 (February 1910), pp. 129-60.

34. ^ Letter from Cram to Willet Studios, June 28, 1912. I am indebted to the late Helene Weis for drawing my attention to this commission and for much additional information on American stained glass studios.

35. ^ Letter from Cram to Willet Studios, July 8, 1912, communicated by Helene Weis.

36. ^ Ibid., "Since these 'Seven Liberal Arts' were the development of Christian impulse during the XIIth and XIIIth centuries the figures should suggest the spirit of that period.

37. ^ See introduction by Jane Hayward in Radiance and Reflection. Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection [exh. cat. The Metropolitan Museum of Art] (New York, 1982), 32-47 and Beth Lombardi, “Raymond Pitcairn and the Collecting of Medieval Stained Glass in America,” in Medieval Art, 185-188. A typescript by Ariel Gunther, 1982, communicated to the author by Nishan Yardumian, explains the stained glass, including the replicas of the Chartres Cathedral transept lancets installed in the Great Hall of Pitcairn's residence at Glencairn.

38. ^ Michael Cothren in Corpus Vitrearum Checklist II, 136; Jane Hayward and Walter Cahn, Radiance and Reflection: Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection [exh. cat., MMA] (New York, 1982), 229-231.

39. ^ Saint was trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Traveling to Europe on a fellowship, he produced watercolors of French and English stained glass that became the illustration for Hugh Arnold’s Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France, London, 1913. Pitcairn also sent him France and England in 1922 with a specific directive of making replicas of windows at Chartres and Canterbury. Pitcairn’s figures at the four prophets carrying the Evangelists from Chartres’ south transept and the patriarch Methuselah from Canterbury are among the results.

40. ^ See especially, the Michigan Law Triangle, Forsyth 1993.

41. ^ Gay Walker, Bonawit, Stained Glass & Yale: G Owen Bonawit’s Work at Yale University & Elsewhere (Wildwood Press, Wilsonville Oregon. 2000); Forsyth 1993, fig. 42.

42. ^ Jean-Jacques Gruber in Vitrail, VIII; Madeline H. Caviness in Stained Glass from New England, pp. 2-5.

43. ^ Church of the Immaculate Conception [Report of the Boston Landmarks Commission, Environment Department, City of Boston] (Boston, April 1987). Although undocumented, the interior is generally accepted as the work of Arthur Gilman, who was working on the construction of Arlington Street Church, Boston, at the same time. The controversy over the preservation of a building of such artistic and historic importance exemplifies the unresolved relationships of the many constituencies claiming rights to American's cultural heritage. See Record of the Landmarks Commission public hearing on the designation of the interior of the church, April 28, 1987, Alliance Letter [Boston Preservation Alliance] 8/6 (1987), 1-3, and broad newspaper coverage in The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix, October 1986.