It seems appropriate that this overview of stained glass from the 19th and early 20th centuries should return to issues crucial to its medieval status: the commemoration of the dead and, through such remembrance, self-definition for the living. All of the religious images discussed within this text were products of societies striving to articulate a link between the past, present, and future. The more conservative Christian confessions were explicit in embracing the ideology of a "communion of saints." This belief posited a real and affective bond linking the members of the community who "are asleep" in Christ with those "who are alive, who remain unto the coming of the Lord." (1 Thessalonians 4:12-14).1 An individual's thoughts or prayers, depending on one's confessional distinction, linked the living with the dead. For the more orthodox, such bonds even allowed the living to participate in the continuing redemption of those already departed. For both the general community and for the specific family, these links were a vivid aspect of community self-identity for the period under consideration.2 An understanding of memorials in the 19th and early 20th centuries entails a compassionate acceptance of these priorities. This, if not style or economics, links the windows in medieval churches to modern times. The glazing cycles meshed the life of a revered individual and the life of Christ, making both present to the congregation as models of behavior and as carriers of the promise of eternal life. The importance of the past was as essential to the 19th-century installation as it was to the 13th; it is simply that new political structures radically transformed the image.

Medieval precedents for commemorative stained glass: the Battle of Crécy

The Court of Heaven, 1357,

commemoration of the Battle of Crécy, 1346,

west window, Gloucester Cathedral,

Gloucestershire, England. Photo: DilifStained glass windows have served to commemorate events of vital national importance, such as of the Battle of Crécy memorialized in the great east window of Gloucester Cathedral completed by 1357.3 At Crécy on August 26, 1346, Edward III (the Black Prince) with a force of 40,000 English soldiers defeated a French force almost three times its size. Froissart (and he was French) tells us that the flower of French chivalry perished in the conflict. The window commemorates the dead, and also the escape from death or the postponement of the passage from this world to the next. A symbol of victory, perhaps, rather than loss, the window dominates the perspective behind the high altar. Its imagery reveals the court and social structure of England, even as it images the approving glances of heaven. Fictive architectural canopies frame a series of figures of knights, kings, ladies (as saints) and Christ, set within the structural architectural parameters of the Perpendicular style. This system remained the most frequent late-medieval schema, whether memorial imagery, donor portrait, or saintly patron. And, as discussed in the analysis of stained glass before the opalescent period, it became the standard 19th-century choice in lancet windows.

The donors of medieval windows, reflecting the economic structure of their time, were invariably of high social rank. Donors of the 19th century were far more varied in class and this greater social diversity influenced religious administrative structure. Except in rare instances, religions were no longer state supported and the clergy no longer could take allegiance for granted. Individual believers became crucial elements of economic survival for a corporate church. In a pluralistic situation such as that of America, it was especially necessary to link the parishioner with both the abstract and the physical organization of the church. Confraternities, new devotional practices, and the emphasis on individual donors for building campaigns all contributed to an active relationship between the clergy and laity.4 Individuals and church societies were responsible for funding windows. The priorities of these groups were reflected in the themes of a glazing program, ineluctably transforming the received canon of confessional imagery. One cannot invite the laity without the process reciprocally transforming the nature of the church itself.

St. Lorenz, Nuremberg: individual patrons’ remembrance of family

St. Lorenz Church,

Nuremberg, 14th-15th

centuries, interior of choir.

Photo: Volker SchlierResearch on late-medieval monuments evidences striking parallels between the mercantile society of America in the 19th century and the burgher societies of the 15th and 16th centuries. Corine Schleif's studies on the church of St. Lorenz, Nuremberg are particularly revealing.5 The Church of St. Lorenz preserves the quintessence of the late-medieval sacral ambiance. The late-Gothic building retains its complement of individually donated furnishings: carved altarpieces of gilded and polychromed wood, sculptured apostles and saints of hewn stone, extensive windows with brightly contrasted stained glass, and small painted epitaphs with delicately modeled details, as well as the church's best-known monuments, Adam Kraft's huge Eucharistic tabernacle and Veit Stoss's

St. Lorenz Church,

Nuremberg, 15th-16th

centuries, interior, detail of

suspended sculpture, the

Angelic Salutation by Veit

Stoss, 1518. Photo:

Volker Schliersuspended sculpture of the Annunciation of the Rosary. A wide circle of affluent citizens from various levels of society competed to furnish the structure within and without. In St. Lorenz, as generally during the Late Middle Ages, the subject matter of the given work was no longer dictated by its position within a unified cycle, nor was the placement of a particular theme fixed by a predetermined program. The themes and the placement of monuments are, for the most part, the result of donors vying for the most prestigious places. The apportioning of the stained glass cycles in many American buildings, for example Trinity in Boston [See Appendix], repeats the pattern observed at St. Lorenz. The donors accrued special merit via the images with which they associated. Schleif observes that the continued use of the church after the Protestant Reformation shifted the emphasis away from the saints to the donors. The altar of St. Bartholomew became known as the Krell altar and the exterior chapel dedicated to St. Anne was at times referred to as the Horn Chapel, because it was donated by Kunz Horn. At other times it was referred to as the Tuchmacherkapelle because it was maintained by the Nuremberg Cloth Makers. Here and in other places families and craft alliances became more tangible points of reference than saints within the shared consciousness of the community.6

Donor identification: Julia Appleton McKim, Trinity Church, Boston

The donor identification has remained the primary association of memorial windows in 19th and 20th-century churches. Churches that have made any kind of record of their windows invariably list the names of the donors, often with little indication of the subject matter of the window. In fact, windows appear to have become in the modern world the most prominent means of the laity's self-expression within the church structure. It may have been, for this reason, far more than a disagreement with La Farge's aesthetics that made plain grisaille windows absolutely unthinkable for Boston's Trinity Church.7 In addition, the modern patrons often exerted much the same artistic and thematic control over memorial images as the Nuremberg patrons.

John La Farge, Presentation

of the Virgin, 1888, south nave,

Trinity Church, Boston.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin

Titian, Presentation of the Virgin,

1535-1538 Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice.

Photograph: courtesy of

ordokalendar.wordpress.com

The south nave window of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple is a memorial to Julia Appleton McKim, donated by her husband, Charles Follen McKim, and her sister Alice.8The donor was clearly a major identification point, and one of the first citations of the window in print refers to the "McKim Window in Trinity Church, Boston."9 McKim was a partner of McKim, Mead, and White, the architects of the Boston Public Library. He selected the artist, John La Farge; he also appears to have selected the model to commemorate his wife's death at age twenty-eight. The central image depends on the painting by Titian, 1535-1538 now in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Venice, and the inscription cites this source. The Latin text is brilliantly evocative of the concept of light: "Shines in glass the distinct and well-known face of the Blessed Virgin as first painted by Titian, and most resembling the beloved wife in whose memory this record shines."10 The Renaissance painting is a huge canvas showing a long stairway, framed at the bottom by a crowd of onlookers and at the top by the High Priest and two assistants. The painting was highly regarded and numerous reproductions in print form circulated from the 17th century onwards. Only the segment showing the isolated figure of the Virgin on the stairs is transferred to the window composition. The figure is framed within the compositional

Andrea Zucchi, 18th century engraving,

Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, after

Titian's painting in the Galleria Accademia,

Venice. De Young/Legion of Honor, Fine Arts

Museums of San Francisco, 1963.30.36385

Photo: courtesy of Fine Arts Museums of

San Francisco design as if it were a relic from the past. At the bottom of the frame, set on another spatial plane and seeming to reflect on the image above, a seated figure plays a lute. Temporal as well as spatial illusionism permeates the interchange.11 It is fruitful, I would argue, to see both the lute player and the image of the Virgin as experiential responses to the art of the past. Such music-making figures appear frequently in Venetian art, particularly at the base of a throne or set within an architectural border, to both frame and honor the subject.12 Both patron and artist were united by a common culture, aware of Italian Renaissance models, exemplified by McKim's work in Boston's library and for the Walker Art Building at Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, for which McKim commissioned La Farge to execute a lunette on the theme of Athens.13

The Ames family: Unity Church, North Easton, Massachusetts

John LaFarge, fabricated by

Thomas Wright, The Angel of Help,

Helen Angier Ames Memorial, 1887,

Unity Church, North Easton,

Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin

Unity Church in North Easton, Massachusetts contains two of the best examples of the new tradition of memorial window.14 Two huge windows dedicated to Helen Angier Ames and Oakes Ames dominate the transepts.15 Designed by La Farge, and produced by Thomas Wright, their iconography combines classical, Early Christian, and Renaissance motifs into a new type of mourning icon. The Helen Angier Ames memorial, The Angel of Help, installed in 1887, shows at its base three personifications directly lifted from classical Greek sculpture. La Farge appears to have been inspired by the relief now known as the Boston Throne, an early 5th-century Greek

John LaFarge, fabricated by Thomas

Wright, The Angel of Help, Helen Angier Ames

Memorial, detail of sarcophagus,1887,

Unity Church, North Easton, Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin altar showing Eros between an image of Persephone with head bowed and Aphrodite looking up with raised hands.16 In the window, Help, a tall standing figure in classical draperies, turns toward Need, who holds out her arms in a gesture of supplication. Sorrow, to the right, leans her veiled head on her hand in a mourning pose that also evokes the reference to representations of Melancholy in the window to Oakes Ames. The Early Christian monogram for Christ, the CHI RHO, surrounded by victor's wreath, appears at the top of the window. This motif was a common component of Early Christian sarcophagi that became during the 19th-century, a staple item in French, Italian, and American museums and private collections. Below the monogram, angels surround a bejeweled sarcophagus decorated with vine scrolls: symbols of eternal life in both pagan and Christian traditions.

The window of Oakes Ames, Wisdom Enthroned, of 1901 evokes a Renaissance "sacra

John LaFarge, fabricated by

Thomas Wright, Wisdom Enthroned,

Oakes Ames Memorial, 1901, Unity

Church, North Easton,

Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinconversazione," a holy conversation among a standing group of saints and the divine presence, emulating models such as Veneziano's 15th-century St. Lucy Altarpiece that La Farge surely must have known from his visits to the Uffizi in Florence in 1894. A finished watercolor sketch for the window does not include inscription bands, although the composition strongly suggests that the text

John LaFarge, fabricated by Thomas

Wright, Wisdom Enthroned, Oakes Ames

Memorial, 1901, detail of Wisdom, Unity

Church, North Easton, Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinultimately incorporated around the side of the window was intended from the beginning.17 The inscription refers to the praise of wisdom in Proverbs 3:15-17. "Wisdom is more precious than rubies and all the things thou canst desire are not to be compared unto her. Length of days is in her right hand and in her left hand riches and honor. Her ways are ways of pleasantness and all her paths are peace."

Solomon, the traditional author of the Book of Wisdom, described Wisdom as a majestic woman "artificer of all." La Farge has presented her as contemplative, assuming the position of Melancholy, and evoking in her pose and architectural setting the young Lorenzo de' Medici in Michelangelo's Florentine tomb monument. (Replicas of the Medici tombs were displayed in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts) The richly draped figure with chin resting on her hand also recalls literary depictions, such as the poet Milton's image of Wisdom as Divine Melancholy in Il Penseroso. The technique used by La Farge to render drapery seems dependent on Early Christian drapery

Archangel, Byzantine,

about

525-550 CE,

London, British

Museum London,

Europe and

Prehistory OA.9999patterns known to him through ivories in London, Paris, Monza, and Rome. La Farge owned a number of reproductions of early ivories, including the superbly carved image of an archangel from British Museum.18

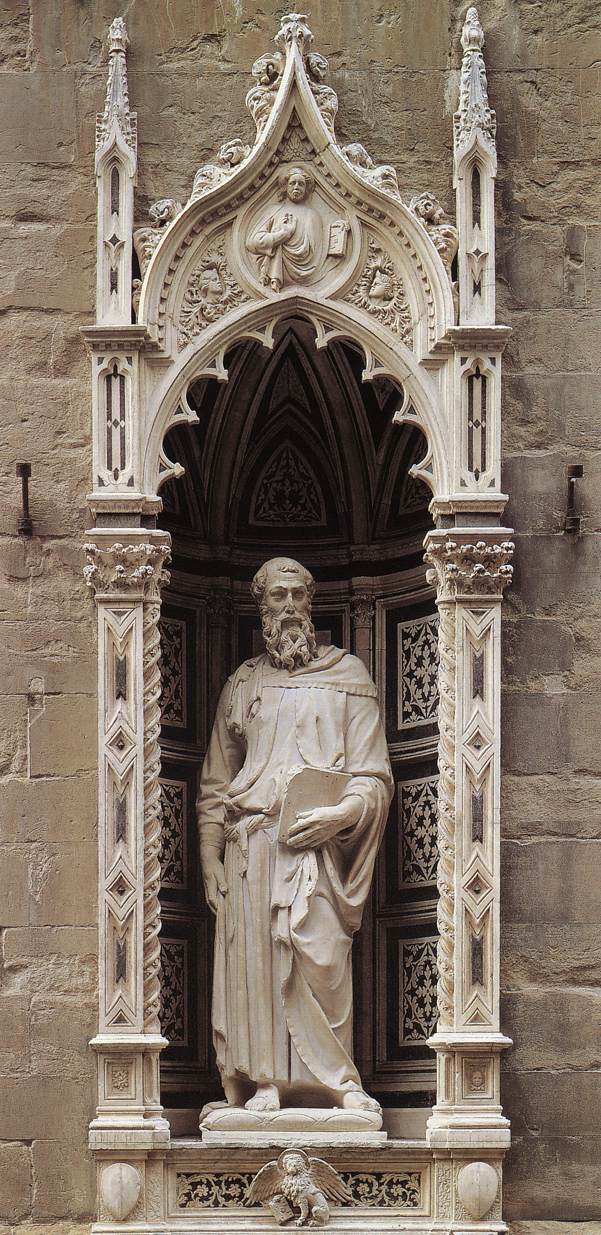

La Farge mentioned in a letter that he patterned the older figure after Donatello's St. Mark made for one of the niches of Or San Michele, Florence.19 The young warrior crowned with laurel also evokes Renaissance prototypes, as exemplified by images of St. Michael in popular Luca della Robbia ceramic plaques. The identification of the youthful figure confirms the complexity of La Farge's iconography. Certainly, he forms a contrast to the bearded figure to the left, and

Donatello, St. Mark,

1411-1413, Orsanmichele,

Florence. Source: Wikipedia therefore personifies "youth" as a complement to "old age." But from the inscription we learn that "length of days" is on Wisdom's right and "riches and honor" on her left, thus the soldier's "honor" in the laurel wreath and "riches" in the golden armor. La Farge has also given us the traditional juxtaposition of the contemplative life in the bearded philosopher and the active life as the youthful soldier. The juxtaposition thus links the two memorials in glass; in Helen Ames' window, the active woman, Need, reaches out to Help while the contemplative shrouded figure of Sorrow turns to comfort from within.

Reconstruction era commemoration of Confederate heroes

Two poignant memorials appear in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy. The state capital building of 1788 had been designed by Thomas Jefferson, modeled after what he believed was an example of Roman Republican architecture. The Maison Carrée of Nimes, southern France, dates from 16 BCE, from which Jefferson took the form of a long rectangle preceded by a deep porch with six columns. Rejecting the Gothic and Renaissance architecture associated with European monarchies, Jefferson wanted the Roman temple to symbolize the birth of a new democracy in the United States. Within sight of this architectural icon, stands St. Paul’s Episcopal Church at Capitol Square in downtown Richmond.

Thomas S. Stewart, Interior looking

towards chancel, 1845, St. Paul’s Episcopal

Church, Capitol Square, Richmond, Virginia.

Photo: authorSt. Paul’s was constructed in 1845 after members of the congregation had journeyed north to study possible models. The building committee was deeply impressed by the Greek Revival style of the church of St. Luke (now the Church of St. Luke and The Epiphany) in Philadelphia, completed in 1840. St. Paul’s hired the building’s architect Thomas S. Stewart to construct St. Paul’s as a very close copy, including its portico of tall white columns over a series of granite steps, a flat-roofed interior with balconies at rear and sides, and windows of clear glass. Toward the end of the

Henry Holiday, Moses leads Israelites from

Egypt, detail, Memorial to Robert E. Lee, 1892,

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Richmond, Virginia.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin19th century, figural windows were added. The practice was widespread, even in the most prestigious early-American structures, such as Trinity Episcopal Church in Newport, designed by Richard Mundy in 1725 after Old North Church in Boston, and ultimately Christopher Wren's St. James in London. Opalescent windows by the Tiffany studios were added to Trinity’s white interior between 1896 and 1910. Boston's Arlington Street Church, Unitarian, built between 1859 and 1861, received a large series of windows designed by Frederick Wilson and fabricated by the Tiffany Studios beginning in 1898. In Charleston, South Carolina, the Colonial St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, completed in 1756, was renovated primarily through the embellishment of the chancel and the inclusion of opalescent windows by Tiffany studios. St. Luke’s in Philadelphia, the precursor of St. Paul’s, added stained glass windows on the ground floor between 1876 and 1899 and series of windows representing the Apostles in the gallery in 1912. St. Paul’s in Richmond followed suit in 1890.

Henry Holiday: Robert E. Lee (allusion to Moses leading his people out of Egypt)

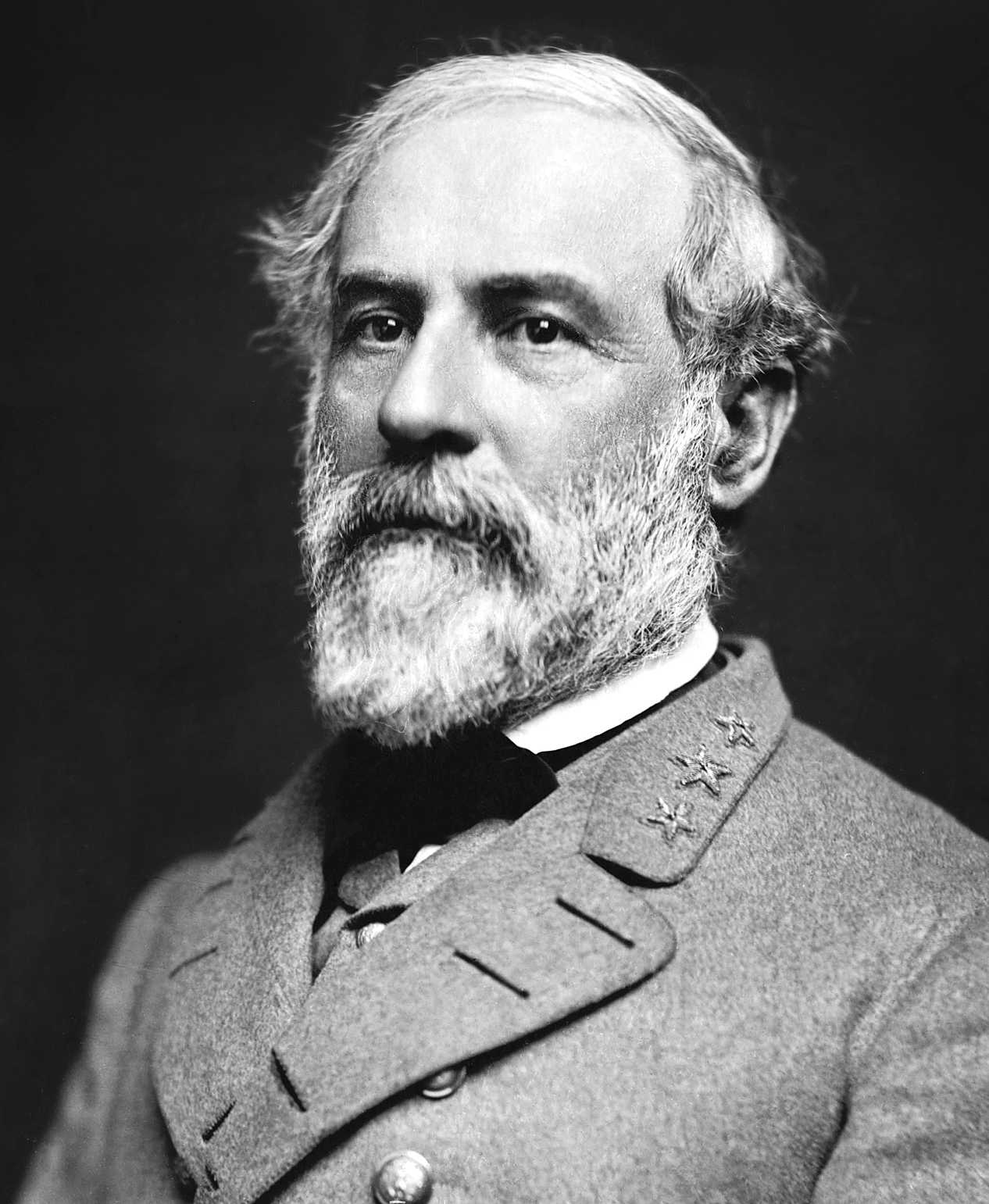

In 1889, St. Paul’s appointed a committee to develop “two conspicuous windows to be dedicated as memorial windows to perpetuate the names of Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis.” Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) was the chief military officer of the Confederacy and Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) its president. 20 Lee has been admired to this day as a brilliant battlefield tactician, and Davis, to some, acquired the mantle of long-suffering champion of the cause of States Rights. 21 Their windows are located midway in the aisles, opposite each other.

The two modern heroes are associated with the biblical prototypes, Moses and St. Paul respectively. Henry Holiday

Henry Holiday, Moses

shown the Promised Land,

Memorial to Robert E. Lee,

upper half, 1892, St. Paul’s

Episcopal Church, Richmond,

Virginia.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin produced a brilliantly drafted window, installed in 1892. The lower level depicts Moses leaving Egypt and above, Moses on Mount Nebo, where God allowed him to see the Promised Land before he died. The window carries a dedicatory inscription “In Grateful Memory of Robert Edward Lee Died October 12th 1870.” The youthful image of Moses leading his people out of Egypt, typical of Holiday’s classicizing manner, presents a dramatic profile of determination. The background is charged with rich details of Egyptian wall painting, architectural relief, and costumes. Moses exits down a set of stairs guarded by a statue of a

Henry Holiday, Moses shown the Promised

Land, Memorial to Robert E. Lee,

detail of the

aged Moses, 1892, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church,

Richmond, Virginia.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinlion. Looking back towards an unseen enemy, he gestures to his followers.

On the balcony level, Moses is now aged. His beard, hair and profile are remarkably similar to

Julian Vannerson,

Photograph of Robert E. Lee in

Confederate uniform, 1863.

Source: Library of Congress

Prints & Photographs Online

Catalogactual portraits of Lee. The Angels carry a banderole, “the eternal God is thy refuge and underneath are the everlasting arms,” a quotation from Deuteronomy 33:27 that if continued would have read, “He will drive out your enemy before you, saying, 'Destroy him!'” Holiday has shown segments of the mountain piercing the striated clouds that separate the divine encounter from the scene below. In darker tones, almost devoid of color, are the Israelites camped before their tents on the plains of Moab. They appear as a great mass of people, looking upwards.

Frederick Wilson,

designer, Tiffany Studios,

Paul before Herod Agrippa,

Memorial to Alexander Jackson

David, lower half, 1896, St.

Paul’s Episcopal Church,

Richmond, Virginia.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinTiffany Studios: Jefferson Davis (allusion to the trials of St. Paul)

Stylistically, the opalescent window of Jefferson Davis by the Tiffany Studios forms a sharp

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios, Paul before Herod

Agrippa, Memorial to Alexander Jackson

David, detail, 1896, St. Paul’s Episcopal

Church, Richmond, Virginia.

Photograph: Michel M. Raguincontrast. Of an arguably greater cost, the window apparently waited until a ladies’ committee raised the funds in 1896. The subject is St. Paul before Herod Agrippa, taken from the lengthy story in the Acts of the Apostles 23:12–26, of the plot by the Jews against Paul’s life. Paul subsequently flees Jerusalem, is apprehended in Caesarea, imprisoned for two years and brought before a series of magistrates until finally he is judged by Herod Agrippa. The inscription “This man doeth nothing worthy of death or bonds” (Acts 26:31) is Herod’s pronouncement of his belief in Paul’s innocence. Clearly the reference is to Davis’s apprehension and imprisonment after the defeat of the Confederacy. Davis was incarcerated for two years before the government decided that proceeding with charges of treason was impractical.

Frederick Wilson’s design is indebted to the widely circulated image, Christ before Pilate executed by Mihaly Munkacsy (1844-1900) of 1881. Indeed, the image of Paul before Herod Agrippa is quite similar to many Tiffany Studios’ windows depicting Christ before Pilate. Paul stands in profile on the left, and to the right the enthroned Herod Agrippa listens intently, his hand on his chin. A crowd of onlookers is seen through the archway. Some have ventured to see in the lean features and short slanting beard of Paul the face of Jefferson Davis. The upper window, in contrast, is

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios, Memorial to

Alexander Jackson Davis: Angels,

1896, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church,

Richmond, Virginia.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin completely celestial; two of Wilson’s characteristic angels display particularly well-fabricated handling of drapery glass and enamel flesh paint. The inscription reads: “Let me be weighed in an even balance that God may know mine integrity” taken from Job 31:6. (The citation of measuring is sometimes translated as “accurate scales.”) Such a reference to Job confirms beyond a doubt the implication that Davis suffered unjustly. We are familiar with the phrase, “the patience of Job,” in refererence to Job being accused by his neighbors and even his wife that his misfortunes were deserved, the result of the errors of his life. In response, Job consistently maintained that he had honored God’s laws. Thus, Davis is presented as a model of integrity and patience.

Memorial Hall, Harvard University honors its Union heroes

The program of Harvard University's Memorial Hall [See Appendix], discussed earlier, continues the fusion of classical, Early Christian, and Renaissance imagery memorializing not only Harvard's student-soldiers but the ethos of an entire generation. Classical and biblical quotations, personal letters of the young soldiers, images of Greek, Roman, medieval, Renaissance, and even early American history all fuse to testify to the meaning of the sacrifice made by the young men fallen in the War between the States. It was indeed, an epic statement summed up by La Farge's Battle Window where the American conflict became the stuff of Homeric legend.

The need for the 19th century to see itself mirrored in the great sweep of the past may be puzzling for the modern audience. Such tendencies were common to the time and particularly essential to the American experience. Isolated in a world ruled by hereditary monarchs, America turned to the past, to Greece and Rome especially, for the historic precedents that would assure her that the sacrifices she'd made were justified and that her future bore promise. Therefore, La Farge's Sanders' Theater Minerva (Athena) in helmet and flowing robe, ties a mourning filet on a classical column. Sarah Whitman's window of Honor and Peace presents two classical warriors in different instances of martial virtue. Honor strides forward wearing his helmet and holding his shield and spear. Peace kneels bare-headed, resting on his shield. Winged female figures stand behind each warrior.

Sarah Wyman Whitman,

Chevalier Bayard Window, 1896,

Memorial to Martin Brimmer, south

transept, Memorial Hall, Harvard

University.

Photo: authorWhitman's transept window fuses personal and corporate imagery.22 The artist

Sarah Wyman Whitman,

Chevalier Bayard Window, 1896,

detail of angelic virtues, south transept,

Memorial Hall, Harvard University.

Photo: author stated that the window was designed to commemorate the forces that inspired the young men who lost their lives in the War between the States, love of the University and love of Country.23She featured the image of the Chevalier Bayard, a model of late-medieval chivalry.24 In 1883, about a decade before this window was made, a new translation into English of the Bayard's life appeared as History of Bayard the Good: Chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, which may have increased the popularity of this theme.25 Bayard in full armor, but bare-headed, stands to the left; Sir Philip Sidney, the English Renaissance poet who died of wounds received at the battle of Zutphen, The Netherlands, stands to the right.26

There is every reason to accept the figures of the soldier and the scholar as idealized portraits of Martin Brimmer, the anonymous donor of the window. Brimmer has been discussed earlier in his role as the first director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the agent for the selection of stained glass by Burne-Jones for Trinity Church,

Sarah Wyman Whitman,

1896, detail of the Chevalier

Bayard, Memorial to Martin

Brimmer, south transept,

Memorial Hall, Harvard

University.

Photo: authorBoston. On his death in 1896, Whitman, an intimate friend of Brimmer, transformed the window into a posthumous tribute.27 The figure of Bayard with its fair coloring, prominent cheekbones, broad forehead and full drooping mustache corresponds to published images of Brimmer.28 The fair haired younger man, Sidney, appears to be a generic image of Brimmer as a youth. It is not a portrait made after any of the historic images of Sidney. All references to Brimmer give special attention

Engraved portrait of Brimmer

by J. A. J. Wilcox, of Boston, in

George Silsbee Hale, Martin Brimmer,

A Memoir [reprint from the

Publications of the Colonial Society

of Massachusetts, vol. 3]

(Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1897),

frontispieceto Brimmer's Huguenot heritage, his studies at the Sorbonne, and his affinity for the French paintings by Rousseau and Millet. It is very likely that the French themes in the window, Bayard who performed heroic service for France's Francis I and Brimmer's namesake, Martin of Tours, a model of virile humility depicted in a vignette at the bottom of the window, reflect Brimmer's pride of heritage and belief in the nobility of public service.29 Brimmer held many non-remunerative offices, as Trustee of the Boston Athenaeum, Trustee of Massachusetts General Hospital, and Fellow and later member of the Board of Overseers of Harvard College from 1877 to 1896, as his position with the Museum of Fine Arts.30

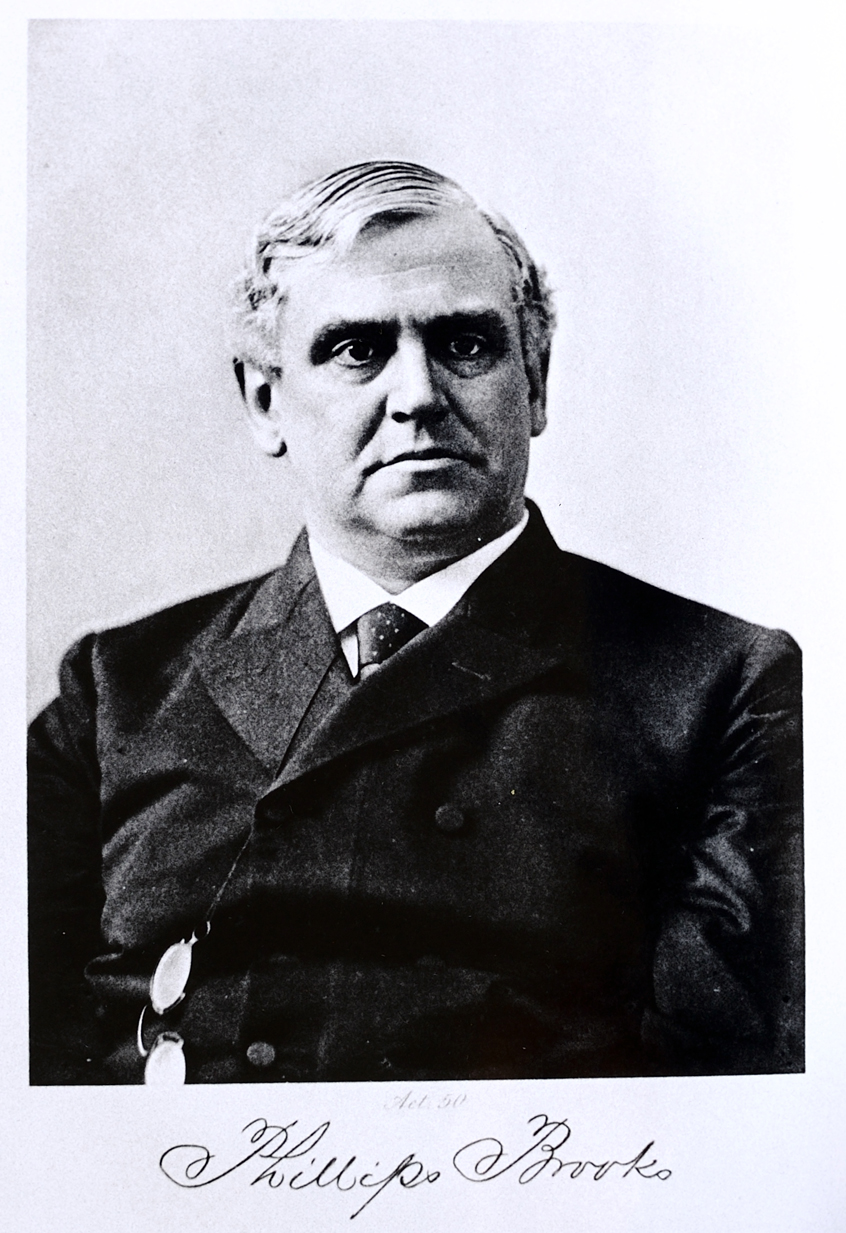

It seems probable that this disguised portrait allowed painters to include recognized portraits in a subsequent window. The window donated by the class of 1855 showing Bernard of Clairvaux and Godfrey of Bouillon was designed by Edward Peck Sperry and fabricated by the Church Glass and Decorating Company of New York in 1902. The theme, like that of the window immediately to the west of La Salle and Marquette, honors military and spiritual leaders. Godfrey, a knight, captured Jerusalem from Islamic control in 1099 and Bernard, a Cistercian monk, preached the Second Crusade in 1145. Both function as symbols of those engaged in God's service of the holy war. Both medieval prototypes appear with the features of their 19th-century counterparts. Godfrey's features are those of Francis Channing Barlow, a member of the class who rose to the rank of Major-General during the Civil War. Bernard is depicted under the guise of Phillips Brooks, also Harvard Class of 1855 and rector of Trinity Church, Boston, who lifted a powerful voice in support of the Union cause. The inscriptions listing "Faith and Hope" below Bernard/Brooks and "Love and Fortitude" below Godfrey/Barlow corroborate the inspirational message of virtue in the service of a just war.

Families and Children

Windows, by their very nature, present a fusion of the artist, patron, site, and material which challenge the post-modern function of painting as a collectible brokered by a gallery system for buyers totally removed from the work's genesis. It is the intrusion of the patrons and their personal priorities that is so insistent, and for certain contemporary attitudes concerning the transcendent impersonality of the fine arts, so disturbing in this medium. From the most sophisticated, such as Harvard's great portraits of model preacher and soldier, to the most intimate local expressions, windows were the most common means of imaging the departed. Roger Riordan, a prominent critic of stained glass during the opalescent era, wrote in a popular journal on domestic furnishing that "Church windows are in most cases memorial windows, and it is generally desirable to introduce a portrait of the person in whose memory they are erected."31 With great frequency the individual portrait, the modern means of producing an authentic likeness, became a part of the commemoration.

.jpg)

Heaton Butler & Bayne,

Christ the Consoler in Modern

Christianity. Memorial to Alice

Weeden Austin and of Clara,

Clarence, and Eugene,

children of John and Susan

Austin, All Saints Memorial

Church (Episcopal),

Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: authorLikenesses of four deceased children appear in a window Christ the Consoler in Modern Christianity .jpg)

Heaton Butler & Bayne,

Christ the Consoler in Modern

Christianity, Detail, All Saints

Memorial Church (Episcopal),

Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: author in All Saints Memorial Church (Episcopal), Providence, Rhode Island. A young woman of twenty-one is depicted full length in a wooded setting, with Christ at her side, his hand raised in blessing. In a radiant cloud above appear the heads of three angels. The heads are unquestionably the younger children named in the inscription (Clara, Clarence, and Eugene), a girl of almost five, a boy of eleven, and another boy of almost seventeen.32 Christ's image is generic, but the young woman and the three angels are quite individualized, leading the viewer to assume portrait likenesses, or at least approximations. Prominent in the window are lilies of the valley, held in the young woman's hand and flowering in abundance at her feet, unquestionably a reference to the lilies of the field of the biblical parable: "Consider the lilies of the field" (Matt. 6:28). If God cares for the lowly plants so that he clothes them in beauty, how much more will he care for the souls of the faithful. The same theme appears in the Sparrow Window by the Tiffany Studios in the Church of the Covenant, Boston.33 A man clothed in Middle-Eastern dress walks along a path, and a sparrow is on the ground. The depiction visualizes the parable's verse "Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? And yet not one of them will fall to the ground without your Father's leave." (Matt. 10:29).

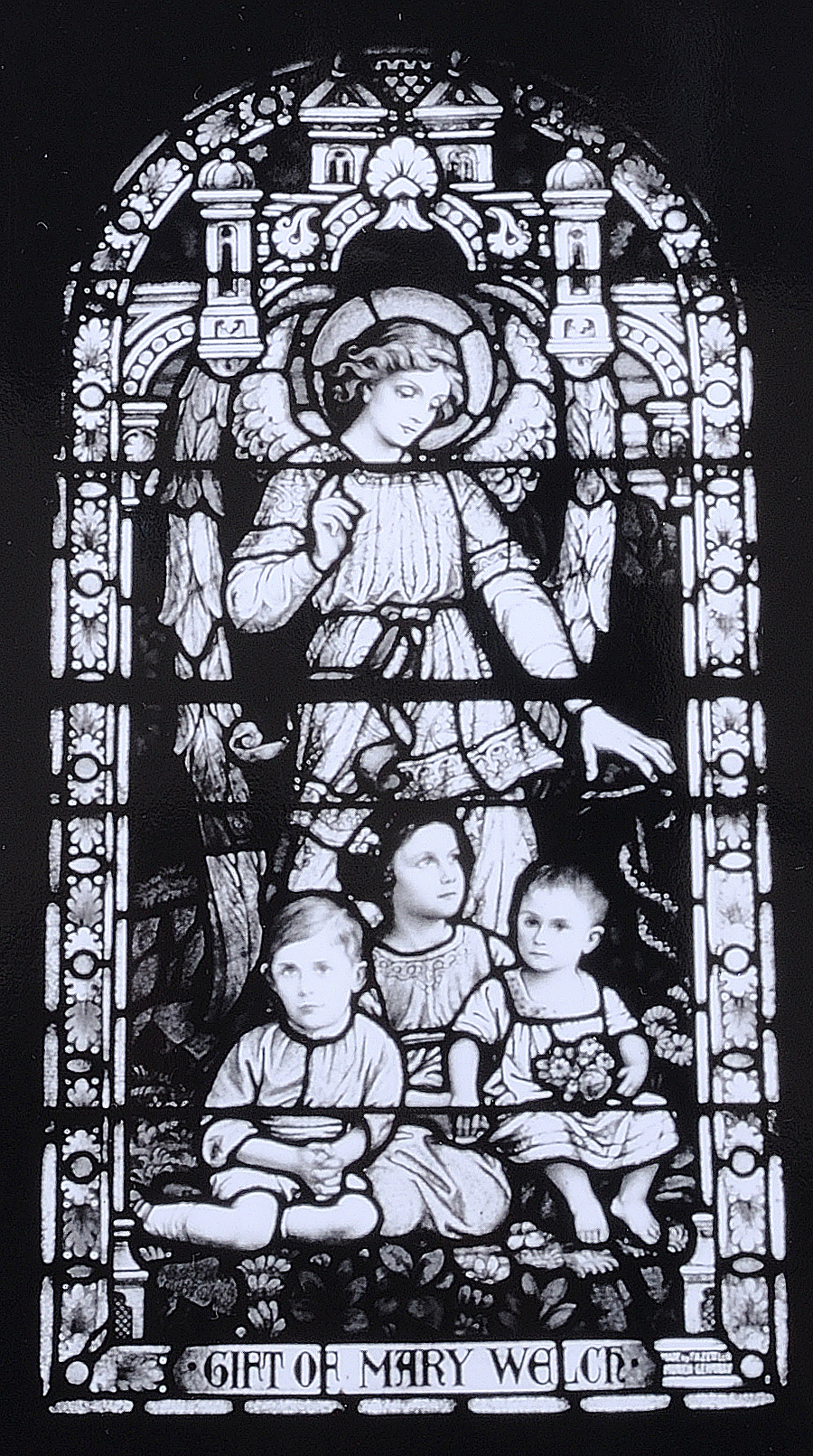

Early deaths of children through illness or through war encouraged the dedication of memorials. The tradition was widespread. Most frequently the subject matter would include an angel carrying a child in its arms, a cluster of cherubim, or Christ among the children. For a young soldier, it was the archangel Michael, or, for a daughter, a young woman framed under an architectural canopy. Often the windows contained imagery referencing precise biographical

Frederick Wilson,

designer, Tiffany Studios,

Sparrow Window, Memorial to

Nathaniel Brimbecom and

Children, Church of the

Covenant, Boston,

Massachusetts.

Photo: authorcircumstances. This was the circumstance of Leland and Jane Stanford whose loss of their only son occasioned their foundation of Stanford University, discussed earlier. The huge program of opalescent windows for Stanford's Memorial Church [See Appendix] replicated Renaissance and 19th-century paintings of religious subjects. Jane Stanford commissioned but one original subject among the major windows, And they Shall See His Face (Rev. 22:4) (often referred to as Lo I am with You Always).34 The design was produced by Antonio Paoletti, the artist who planned the church's mosaics. In a group of figures, a woman cradles a dying child in her arms and a man looks up to a vision of Christ surrounded by brilliant light.35 On the right an angel, already suspended from the earth, supports a boyish figure clothed in white robes. The young face is close to being a portrait.

Jane Stanford's letters concerning the entire decorative program of the church confirm the family orientation, seen continually in the art under discussion. She approved of the mosaics; "the designs met with my hearty sympathy in the story told of the welcoming back to the heavenly home of the Son of God, and the second picture showing our Savior enthroned with His loved ones around Him and the Cross in the back, forgotten."36 The window needed no dedicatory inscription to establish it as an autobiographical reference to Jane Stanford's belief that she was comforted by divine aid for the loss of her only child, and that her child had returned to his heavenly home. Like the enthroned Christ "surrounded by his loved ones," the imagery of the church reflected Jane Stanford's conception of family ties as an integral part of both social and individual integrity, and the structure of human happiness in the world to come.

Photography at the service of the commemorative portrait in memorials

Portrait of Philips Brooks,

taken from Alexander V. G.

Allen, Life and Letters of

Phillips Brooks, New York, 1901.

Portrait of Francis Channing Barlow.

Photo: civilwartalk.co

Given the context of family ties to both the exalted and the humble client, both American and European studios appear to have been willing not only to personalize memorials but to include portrait likenesses to suit the patron. Sperry had access to photographs of the young Francis Channing Barlow and a portrait of Phillips Brooks in later years for his work on the Bernard-Godfrey window for Harvard.37 The window in All Saints, Providence was produced by the London studio of Heaton, Butler & Bayne, presumably after photographs.38 As late as 1945, the London studio of William Glasby included portrait likeness for The Peachtree Christian Church, Atlanta Georgia. William's daughters, Barbara and Dulcima Glasby, designed almost all of the aisle

Barbara and Dulcima

Glasby, Parable of the Great

Feast, 1945, Memorial to Jimellen

Gottenstrater, aisle window,

The Peachtree Christian Church,

Atlanta, Georgia.

Photo: author windows after the themes of the parables of Christ. The Parable of the Great Feast shows the king welcoming guests to the feast, among them a little girl bearing the features of Jimellen Gottenstrater, to whom the window is dedicated.39 The difference between individualized features of the child and the generic images of the various other guest is striking, and church records substantiate the family's desire for a portrait likeness. Catholic memorials were not excluded from this trend. The window of the guardian angel, a common theme for children's memorials, in St. Boniface Church, Chicago shows three children of

F. X. Zettler, Guardian

Angel, 1905, Gift of Mary

Welch, St. Boniface Church

(Roman Catholic).

Photo: Rolf Achillesvarious ages and individualized physiognomies.40 The Munich firm of F. X. Zettler installed the window in 1905. The children sit on a grassy mound, the youngest holding flowers while and angel extends its hand protectively over the group at its feet. The angel's face, in contrast to the children's, presents the neutral and harmonious features of a heavenly apparition.

Turn of the century painting and photography

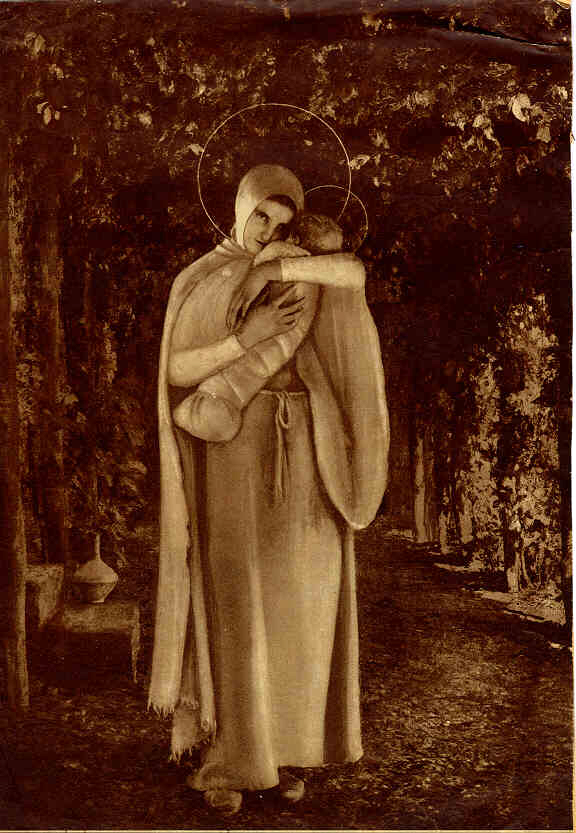

The use of photography for religious work has been a little explored theme, and one deserving of much greater attention. From the 1860s onward, French painters, among others, had been particularly at pains to unite the realistic and the visionary, as exemplified by works such as Edouard Manet's Dead Christ with Angels of 1864.41 In this painting Manet guides the viewer into imagining that Mary Magdalene is meditating on Christ's resurrection; the viewer then sees Christ through her mind's eye. During the 1870s and early 80s, however, artists began to harness photography's

Pascal Adolph Jean

Dagnan-Bouveret, Madonna of

the Trellis 1888, present

location unknown. Photograph:

after Gabriel P. Weisberg,

Against the Modern:

Dagnan-Bouveret and the

Transformation of the

Academic, fig. 107 potential to augment both reality and transcendence.42 Pascal Adolph Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, one of the most popular French Salon painters of the end of the century, relied on photography to provide compositions, figural groupings, models, and lighting effects. His Madonna of the Trellis, 1888, which became a much-used model by Tiffany, presented the Virgin and Child as a woman draped in white robes, cradling a child in her arms, and surrounded by an arbor.43 The artist worked directed from a model but took photographs of the precise pose, later working from the photograph without the model. He routinely posed members of his family in his studio, photographed them in preconceived poses, and integrated the photographic reference into religious scenes such as his Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus painted 1896-97.44 In a manner strikingly similar to what we have seen for the memorials at Harvard for Martin Brimmer in 1896 and Phillips Brooks and Francis Channing Barlow in 1902, the finished product retains the photographic verisimilitude. Unlike earlier users of photography, these religious painters, and in this I include the designers of windows, exploited the precise portrait-like nature of the characters to personalize the transcendental nature of the themes. By realizing the specificity of the portrait, such as those of Dagnan-Bouveret's wife and son kneeling at the right of the table in Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, the viewer sees himself or herself also within reach of the living Christ. In fusing the image of Phillips Brooks with that of Bernard of Clairvaux, the viewer understands that for each time and each place, abstract virtues of religious dedication and moral conviction are made operative through specific individuals and their actions. History does not simply happen. Great traditions live on because of personal decisions made by individual human beings accountable for their action or their inaction in the face of challenge.

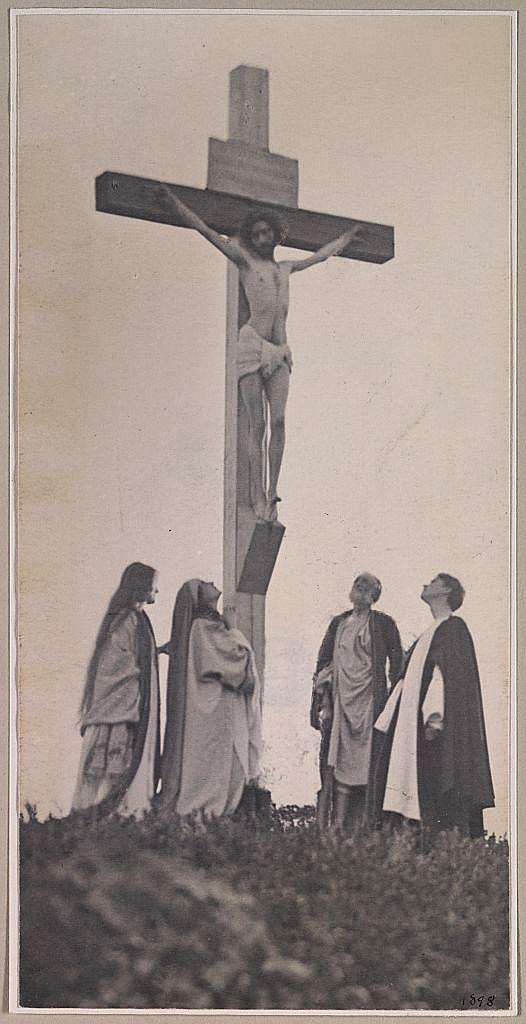

F. Holland Day’s photographic reenactment of the life of Christ

F. Holland Day,

Crucifixion, [Crucifixion, frontal,

with Mary, Mary Magdalene,

Joseph and St. John (?)], 1898.

Photograph: Source: Library

of Congress Prints &

Photographs Online CatalogAt the same time in America, photographers such as F. Holland Day, a friend of Ralph Adams Cram, were concentrating on pioneering religious narratives. Day developed suites of photographic themes, many illustrating specific biblical stories in an effort to meld the new vehicle of photographic realism to religious sensibility. His efforts to stage the Crucifixion have been the most noted.45 Day prepared for the role of Christ himself, through a regimen of spiritual as well as physical training in a plan to use the new medium to bring most vividly and realistically the issues of an emaciated, suffering body before the viewer's eyes. The Seven Words are a series of close-ups self-portraits of Day portraying Christ's last moments. It is believed that Cram also acted roles in these staged images. Day was equally indebted, however, to the heritage of Old Master paintings and owned a considerable number. One showing Velasquez' Crucifixion remained in his home, suggesting that it, along with paintings by Murillo and Ribera that Day had mentioned seeing in the Prado, had exerted a considerable influence on the staging of his Calvary scenes. As with other issues discussed in these essays, Day's example explicates the complexity and interrelatedness of patronage, viewer reception, dissemination of images of the past, and modern technology. The images are disconcerting to the modern eye. The ability of the photograph to so embody the remembered specificity of our lives seems at odds with the abstract nature of faith and the non-specificity of the biblical account. Yet these developments in easel painting, photography, and the monumental arts are extremely valuable for their ability to mirror the efforts of an age to retain both its heritage of traditional faith and its fascination with the increasingly objectified world.

Emmanuel Church, Boston: Pilgrim’s Progress

Disguised portraits and transcendental meaning may also appear in a turn of the century window in the north transept

Frederic Crowninshield, Pilgrim’s

Progress, Memorial to Mrs. Howard

Payson Arnold, 1899, Emmanuel Church,

Boston. Photo: author of Emmanuel Church, Boston. The memorial window to Mrs. Howard Payson Arnold (1820-1897), whether personal or not, clearly praises female virtue in a highly articulate and arresting image. Pilgrim's Progress was designed and fabricated in 1899 by Frederick Crowninshield, in memory of his mother, who had died in 1897. Crowninshield is responsible for windows in Memorial Hall [See Appendix].46 The image is based on a passage early in John Bunyon's text of 1678. After passing through the Slough of Despond, Christian comes to a Palace Beautiful. Piety shows him the Delectable Mount which Crowninshield depicts as a lush landscape with flowing waters, fruit-laden trees, and a classical terrace of rose-pink marble. The

Frederic Crowninshield,

Pilgrim’s Progress, detail, Memorial to

Mrs. Howard Payson Arnold, 1899,

Emmanuel Church, Boston. Photo: authorinscription reads, "Then Pilgrim asked the name of the country; they said it was Emmanuel's land." They, of course are the four Virtues who have greeted Pilgrim on his entrance to the Palace Beautiful. Piety, dressed as a nun in white robes is the Virtue who actually shows Pilgrim the vision. Bunyon named Piety and her companions, Discretion, Prudence, and Charity, but he did not identify their attributes. The artist was forced to evolve his own visual symbolism. He did so in the same manner as the practice of architecture and figural arts of his time, eclectic images derived from a composite tradition. He gave Discretion the keys that are an attribute of Temperance. Prudence holds a book and a cross, often the attributes of Faith, and wears the victor's laurel wreath and armor often associated with Fortitude. The open armed gesture of the third woman might be enough to label her as Charity, but the two cornucopias on her dress and her inscribed halo secure her identity.

Crowninshield exploited the variegated colors in the opalescent glass to suggest a verdant countryside bathed in soft light. Christian and the four Virtues wear muted tones of white, beige, and gold, allowing the blue, green, and pink of the landscape to dominate. Landscape of this type was perhaps the most innovative American contribution to memorial iconography. Associated with the studio of Louis Comfort Tiffany, but common to much glass from 1890 through the 1920s, the landscape became a metaphor for eternity. As exemplified in Crowninshield's work, the newly developed American opalescent glass allowed the artist to paint with light as well as color and to achieve effects startlingly like those of nature herself, or perhaps of nature transfused with heavenly light.

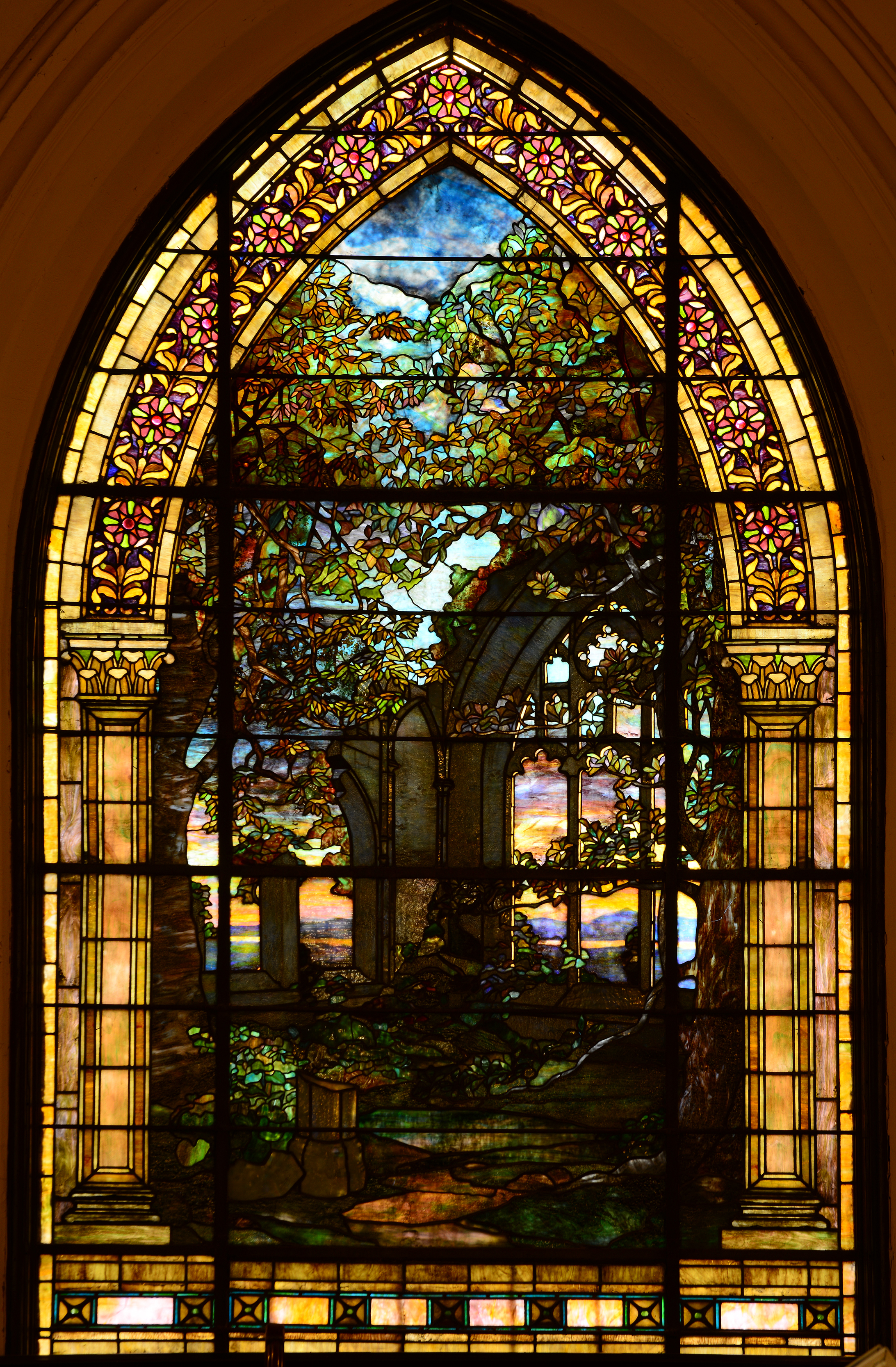

Landscape on its own

Tiffany Studios, At

Evening Time it Shall be Light,

1901, Memorial to James R.

Taylor, First Presbyterian

Church, 124 Henry Street,

Brooklyn. Photo:

Michel M. RaguinAlthough recent studies of landscape painting have connected the genre with Victorian transcendental philosophy, scholars have been neglectful of the theme in stained glass.47 Since the landscape window occurred so often in an overtly religious setting, its capacity to reflect philosophical attitudes is of great importance. Tiffany Studio’s At Evening Time it Shall be Light, 1901, from First Presbyterian Church, Brooklyn exemplifies the ability of the subject alone to convey transcendental meaning.48 The title is taken from the prophet Zechariah (14:7), but its relevance for the time was grounded in a belief that the true promise of God’s love is found in nature. Half-hidden by trees, ruined arches of an abandoned church are silhouetted against the blue, orange, and purple of the setting sun. Luxuriant foliage dominates the composition. The varicolored green hues proclaim life amidst the decay of the building. Human efforts, even those praising the divine, will pass, but God provides constant renewal in the world around us. The picture is framed by golden Corinthian columns that support a floral arch, as if the motif of organic growth even overwhelms the architecture.

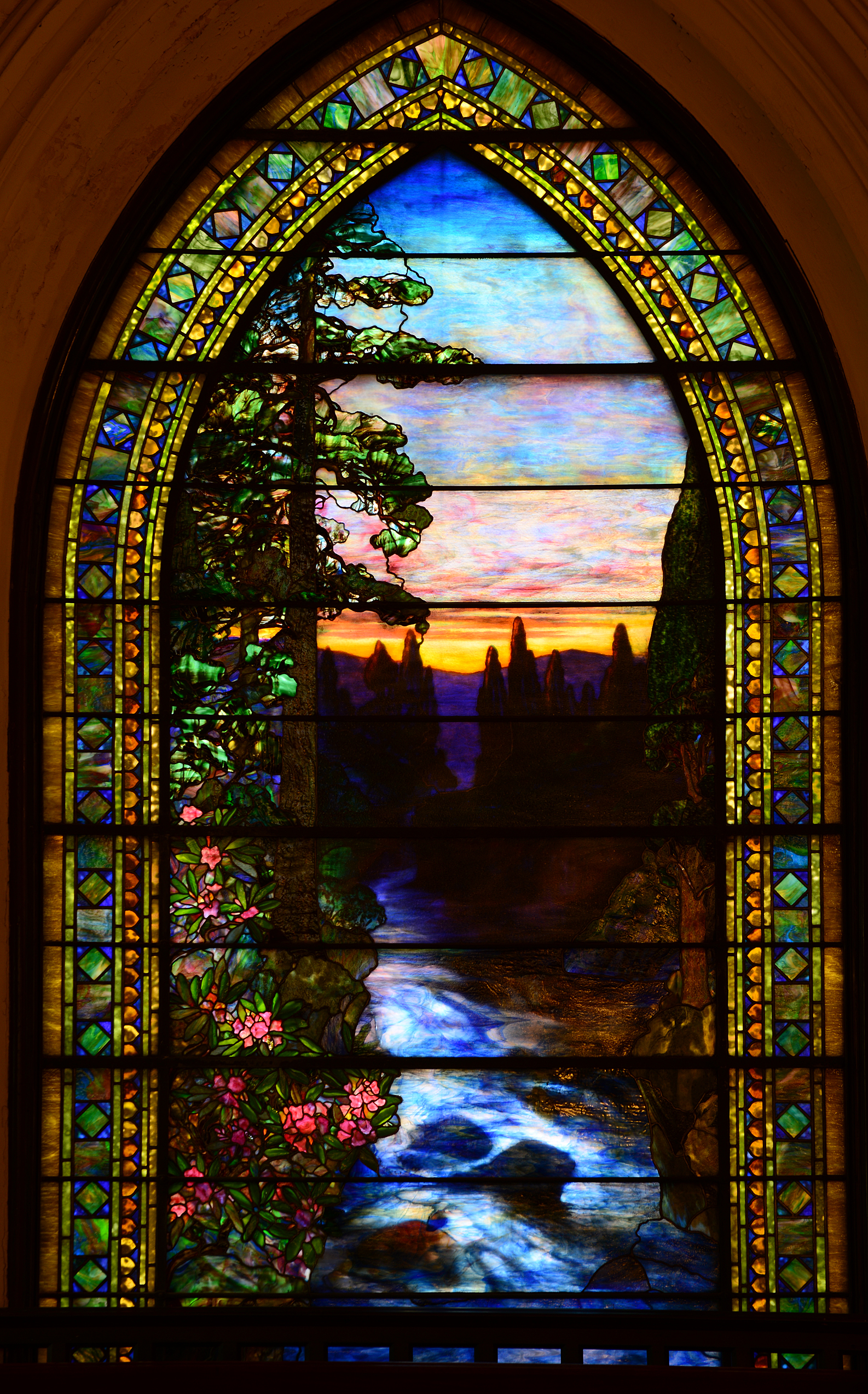

Such landscapes became intensely popular and were produced with astonishing variety until the closing the studio in 1932. A visibly later style appears in the River of Life window

Tiffany Studios, River of

Life, 1921, First Presbyterian

Church, 124 Henry Street,

Brooklyn.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin of 1921 at First Presbyterian.49 Flowing past dark fir trees, a rushing river is bordered by thickly clustered mountain laurel in full bloom. The sun, setting or rising, strikes the water, creating a variegated shimmer of blue and gold that responds to the blue and gold striations of the sky. Confessional motifs are absent; rather we see light as a evoking transcendence, depicted in the window as image and also experienced through the window physically. Such windows are frequently accompanied by texts that corroborate the importance of the contemplation of nature to see God. The Psalms were a frequent source, as exemplified by a window in the Theodore Parker Unitarian church in West Roxbury of 1927. A mountain lake, framed by hills, irises, and morning glories, extends across the triple light window. The inscription reads: "I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills from whence commeth Thy help" (Psalm 121:1). 50

The American opalescent landscape proclaimed exactly what American landscape painting evoked: the existence of God immanent within his creation. The subject made it unusually flexible, equally at home for domestic use, exemplified by the original destination for

Window on stairwell landing, anticipated

setting for Tiffany Studios’ Autumn Landscape,

1923-1924, now Metropolitan Museum of Art;

Loren D. Towle estate, now Newton Country

Day School of the Sacred Heart,

Newton, Massachusetts. Photo: authorTiffany’s Autumn Landscape now brilliantly installed in Charles Engelhard Court of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Presumably designed by Agnes F. Northrop (1857–1953), the widow had been commissioned for the stair landing of the Loren D. Towle estate in Newton, Massachusetts. Towle began construction of the Tudor-Revival style building in 1920 but died in 1924 and the window was never installed. 51 In 1925 the building became the property of the Sisters of the Sacred Heart who transferred their Boston school to the site, where it became Newton Country Day School. Few works in the Museum’s collection make such an impact on the viewer. The effect is immediate; the autumn colors evoke idyllic days in New England woods, evoking the intensity of Henry Thoreau’s praise of the natural world in Walden.

The painters of the luminist school, such as George Inness, saw in the revelations of light the manifestation of the transcendental nature of God. Medieval miracles were eschewed by most Protestant programs, the miracle of the universe being viewed as the truer demonstration of God's omnipotence. The painter in oils could only imitate light, but the stained glass artist could incorporate light itself as an active element of the image. Invariably the owners and caretakers of windows will comment on the times of day when the opalescent glass takes on different moods. The effect that an overcast day, a snowy background, or an early morning may have on the window is considerable. The window became a kinetic object, changing with light, but also, like the 19th-century academic images in glass, designed to move and engage the spectator.

As we began this discussion, we return at the end to issues of tradition and change. Landscape, the 19th-century's dominant aesthetic form, became its new memorial icon.52 Although the landscape window was unknown in the Middle Ages, medieval aesthetic sensibilities reappeared in this new genre. The issues activating the new window are precisely those at play in medieval glass. Material form, subject matter, and the spectator's receptivity are fused. The landscape window has become a functioning whole. The sensual delight in the fluctuating color and the changing light, that is, immediate experience, has superseded a literate reading as the "iconographic" message. We do not even have to read the inscription to know that the object images a soul at peace, evoking memories as sensually resonant as those of a spring evening in a flower-laden woodland. The story is not something read or remembered; it is the experience of the window itself. Commemoration of the dead, as always, became self-definition for the living. For the new society, the personalization of the generic experience of nature emerged as the very means of transcending a finite world. The landscape window is both of this world and beyond it, and as such, is arguably art in the same tradition as its predecessors at Chartres.

REFERENCES

![]()

1. ^ This text formed the Epistle read at the Roman Catholic Mass of the Dead. For the growth of these ideas see Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (Chicago, 1981), esp. 50-68.

2. ^ The complex issue of the authority of the church to function as a ritual "gate" between the living and the dead is impossible to treat here at length. The question of indulgences for the redemption of the souls in purgatory, the belief in a Second Coming of the Savior, or the "resurrection of the dead" as phrased in the widely shared prayer called the "Apostles Creed" indicates the widespread importance of such ideas.

3. ^ A much admired window. See Connick 1937, collotype V.

4. ^ Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (New York, 1969); Taves [1986] 1990.

5. ^ Corine Schleif, Donatio et Memoria, Stiftung, Stifter, und Motivationen an Beispiele aus der Lorenzkirche in Nürnberg (Berlin, 1990).

6. ^ Schleif has remarked (College Art Association, 1989) that for most art historians, yet another spatial ambient would be in force in St. Lorenz. "We would sense little of the sacral topography and perceive less of the Nuremberg social structure. Our perceptions, formed by our shared experiences mediated by books and reproductions, would place us in the presence of Albrecht Dürer, Veit Stoss, Peter Vischer, and Adam Kraft."

7. ^ See above. Significantly, the window of Christ Blessing the Little Children was given by Robert Treat Paine Jr. prominent member of the church's Window Committee, in memory of his great grandfather, Robert Treat Paine. Trinity Church Archives, letter from Paine of July 11, 1876. Fichera 1982, p. 51.

8. ^ The window was installed in 1888 and is inscribed "PLACED IN LOVING MEMORY OF JULIA APPLETON / 1859-1887 / BY HER HUSBAND CHARLES F MCKIM AND HER SISTER ALICE."

9. ^ Clara Erskin Clement, "Later Religious Painting in America," The New England Magazine 12/2 (April 1895), 132.

10. ^ NITET VITRO VIRGINIS BEATAE FACES A TITIANO PRIVS DEPICTA CONIVCI DILECTA SIMILLIMA CVIVS HAEC RECORDATIO LVCET.

11. ^ The cartoon for the Suonatore (Luteplayer) is now in the collection of the Worcester Art Museum, 1907.4. See Half a Century of American Art (exh. cat. The Art Institute of Chicago) (Chicago, 1940), 29, pl. VIII. The painting had been exhibited in 1890 with the title "Child Playing upon a Guitar, Italian Motive".

12. ^ It is possible that the juxtaposition of Titian's painting and paintings such as Giovanni Bellini's San Giobbe Altarpiece or a similar composition by Vittore Carpaccio, The Presentation of Jesus in the Temple with Minstrel Angels, within the Gallerie dell'Academia in Venice encouraged the association of architectural frame, detail of the Virgin, and lute player in La Farge's composition. At this time La Farge would have know these images from publications.

13. ^ Weinberg in La Farge, p. 187, fig. 140.

14. ^ See for both windows Weinberg 1977, pp. 395-7, 404-6. The installation of La Farge's windows must be set in the context of the profound renovation of the town of North Easton by Frederick Lothrop Ames and Oakes Angier Ames, the grandsons of Oliver Ames, the founder of the family fortune through production of lightweight and economical shovels in the first half of the 19th century. See Robert F. Brown, "The Esthetic Transformation of an Industrial Community," Winterthur Portfolio 12 (1977), 35-64. The town was restructured between 1877 and 1884 by the buildings and landscaping of Henry Hobson Richardson and Frederick Law Olmsted, which included construction of the Oliver Ames Free Library, the Oakes Ames Memorial Hall, additions to Frederick Lothrop Ames estates, and the North Easton railroad station. The window of Helen Angier Ames was given by her brother Frederick Lothrop Ames (who commissioned La Farge for the windows of his Boston residence). The late Henry La Farge suggested in a letter to the author August 21, 1982, that the windows may have very personal resonances. For the window of Oakes Ames, given by his four grandsons, "the aged figure at left would personify the elder Oakes Ames, the dynamic capitalist and builder of the Union Pacific Railroad who became embroiled in the Crédit Mobilier - the device employed to finance the gigantic enterprise - but who as a member of Congress was censured in 1873 for improper handling of funds, resulting in a stroke leading to his death, leaving his affairs in deep trouble. The figure of Youth with sword, at right, would personify the two sons (Frederick Lothrop Ames and Oakes Angier Ames) who successfully reorganized the Union Pacific, not only reaping the benefits of their father's expertise, but also witnessing his exoneration by act of the Massachusetts legislature in 1883. And the enthroned figure of Wisdom would personify the ultimate triumph of justice." It appears reasonable, as discussed earlier, to see a window of this complexity with several layers of meaning.

15. ^ The original triple lancet windows were removed to allow the 18 by 12 foot unbroken expanse of glass. The original elevation is preserved in a photograph in the parish archives. See above, Chapter 5, for collapse of the La Farge Decorative Art Company conditioned by dispute over the Helen Angier Ames window.

16. ^ Jane Dillenberger and Joshua C. Taylor, The Hand and Spirit: Religious Art in America 1700-1900 [exh. cat University Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley] (Berkeley, 1973), 164, No. 110. The relief was only acquired by the Museum in 1893 but had become well known via photographs and printed reproductions since its discovery in the 1820s. The sculpture was likened to the so called Ludovisi Throne in the Museo del Terme, Rome. Mary B. Comstock and Cornelius C. Vermeule, Sculpture in Stone (Boston, 1976), 20-25, No. 30. Accession no.08.205. I am grateful to James Yarnall for reference to the Berkeley exhibition.

17. ^ Los Angeles County Museum of Art 33.11.5, Gift of Miss Bella Mabury. The sketch measures 17 13/16 by 11 13/16 inches and was once in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. William Preston Harrison.

18. ^ Catalogue of the Art Property and Other Objects Belonging to the Estate of the Late John La Farge, N. A. [sale cat. The American Art Galleries] (New York, March 29-31, 1911), Nos. 277-82, 294. See ivory diptych from Monza as model for La Farge's Seated Philosopher installed 1883 in the Crane Memorial Library, Quincy, Massachusetts: Weinberg 1977, pp. 372-3, figs. 275-7. La Farge's replicas appear to have been actual size copies. The ivory leaf of diptych with figure of an archangel was probably carved in Constantinople during the first half of the 6th century. British Museum, London, EC 295: Ernst Kitzinger, Early Medieval Art (Bloomington, Indiana, 1940. repr. 1964), 23-4, pl. 8. The ivory was well known at the turn of the century and included in the 1901 edition of Walter Lowrie's Monuments of the Early Church (New York, 1901), reissued as Art in the Early Church (New York, 1947, repr. 1969), 170, pl. 105a. For museum copies of ivories see R. Aaron Rotter in Medieval Art, 102-105, Nos. 20-25.

19. ^ Weinberg 1977, p. 406. La Farge worked from a photographic reproduction and was articulate about his wanting his audience to recognize the source. It is useful to realize that although La Farge's first visit to Italy had been in 1894; printed sources of Italian art both before and after his trips would hold an important place in the selection of his imagery. Ultimately, given the Old Testament sources of the window, one can also imagine an allusion to Solomon in the figure of Age and to David in the figure of Youth.

20. ^ St. Paul’s records that: The General Robert E. Lee and his wife were lent a pew and attended services at St. Paul's whenever possible throughout the war. In 1862, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was confirmed as a member of the parish. Many male parishioners gave their lives in battle. The church undercroft was used as a hospital for wounded soldiers. While attending service on Sunday, April 2, 1865, President Davis was delivered a message from General Lee stating that Lee had to withdraw from Petersburg, and thus could no longer defend Richmond. Davis quietly left the church, and evacuated the Confederate government and army from the city that afternoon. Windows of Grace: A Tribute of Love, (Episcopal Church Women of St. Paul’s, Richmond, 2004).

21. ^ Richmond was evacuated as Union troops led by Ulysses S. Grant entered the city on April 2, 1865. Davis was apprehended on May 10, 1865 in Irwinville, Irwin County, Georgia and subsequently imprisoned in Fortress Monroe on the coast of Virginia. Charges of treason against Davis were ultimately dropped in February of 1869. Many of Davis’s views can be found in his books: The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, New York, 1881, and A Short History of the Confederate States of America, New York, 1890. Although first interred in New Orleans, his body was transferred to Hollywood cemetery in Richmond.

22. ^ See Stacy Treuber, "The Literary and Visual sources of the Brimmer Window at Harvard's Memorial Hall" in Raguin 1993.

23. ^ Harvard Guide, p. 89; Hammond 1978, p. 282.

24. ^ The theme had been proposed in 1874 for the first window of the Hall. See Appendix.

25. ^ 1883 London. The original biography was published anonymously in 1527 by a "Loyal Servant" identified later as Jacques de Mailles. A modernized French version was made by Lorédan Larchey in 1822. In 1847 a translation into English appeared by Gilmore W. Simms, The Life of the Chevalier Bayard: "The Good Knight" Sans peur et sans reproche," New York, Harper & Brothers. The Chevalier continued to be cited in popular compendia of heroic models of the time, for example, Great Men and Famous Women Charles F. Horne, ed. (New York, 1894) vol. 3, 145-153. These were most frequently illustrated, often with steel engravings.

26. ^ Sidney is also represented in the Hall by a window produced by Cottier & Co. in 1879. Hammond 1987, pp. 116-120. His physiognomy is close to extant Sidney portraits and bears no resemblance to the figure in the transept.

27. ^ For further information of Whitman see Hammond 1979, pp. 273-304, and important studies deposited with the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College. See also Dina Jones "A Feminist Re-viewing of Sarah Wyman Whitman"; Jennifer Fox, "The Dinner Party: Sarah Wyman Whitman through Fiction; Nora O'Connell, "The Education of Women: Radcliffe and Sarah Wyman Whitman" and Virginia Raguin, "Opalescent stained glass and the Context of Sarah Wyman Whitman" in Raguin 1993.

28. ^ Engraved portrait of Brimmer by J. A. J. Wilcox, of Boston, in George Silsbee Hale, Martin Brimmer, A Memoir [reprint from the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, vol. 3] (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1897), frontispiece.

29. ^ Brimmer himself apparently supplied the Latin translation from a French source for the St. Martin inscription, "If my labor can serve thee, I will not withhold it". Harvard Guide, p. 90. The selection of Martin and the link with a model of Sir Philip Sidney may have been suggested by the long and engaging description of Martin's charity in John Ruskin's Bible of Amiens. Ruskin sent a copy of the first part of the book, containing the reference to Martin and Sidney, to Charles Eliot Norton (an intimate of Brimmer) in 1880. In describing Martin's parting of his cloak, Ruskin judged, "No ruinous gift, nor even enthusiastically generous: Sidney's cup of cold water needed more self denial..." Ruskin [1880-4] 1908, p. 41.

30. ^ Samuel Eliot, "Memoir of Martin Brimmer," Massachusetts Historical Society Transactions (April, 1896), 586-598.

31. ^ Riordan 1885, p. 132. Characteristically, William Willet, head of the Willet studios, argued after World War I for the "ideal" aesthetic memorial against "practical" commemoration of the dead through "office buildings, spacious docks, swimming pools, (or) milk kitchens," in "Stained Glass as Memorials," Stained Glass 15, No. 7 (1921), 8-9.

32. ^ The inscription reads: "To the glory of God and in loving memory of Alice Weeden Austin born Oct. 11th 1874 died Nov. 24th 1895. Blessed are the Pure of Heart. Also of Clara M. born August 9th 1859 died Aug. 3rd 1865/ Clarence H. born August 5th 1866, died Dec. 14th 1877/ Eugene A. born July 16th 1861 died July 8th 1878, children of John and Susan J. Austin." I am grateful to Kerry Sullivan and Jennifer Lee Cadero-Gillette who assisted in the survey of the windows of this church and others in Providence.

33. ^ Koch 1966, p. 6.

34. ^ The inscription from Revelations is on the lower border of the windows. It is the only text not drawn from the Gospels, therefore, the only prophetic or prospective reference in the program. The passage is taken from the last Chapter of Revelations, describing the complete harmony and bliss of a transfigured world where (Rev. 12:5) "night shall be no more, for the Lord God will shed light upon them; and they shall reign forever and ever."

35. ^ Stockholm 1980, p. 71.

36. ^ Letter from Jane Stanford to M. Camerino, Venice, March 1, 1902. Stanford University Archives.

37. ^ Harvard Graduates' Files, Harvard University Archives; Allen 1901, vol. 3, frontispiece.

38. ^ Signature on the window. See S. B. M. Bayne, Heaton Butler & Bayne: Un Siècle d'art du Vitrail. A Hundred Years of the Art of Stained Glass (Lausanne, 1986). In 1888 the annual catalogue of the Gorham Company, New York, described it an American agent for Heaton, Butler & Bayne. Samuel Hough, "Notes from the Archives: Gorham's Stained Glass," Silver 22/2 (1989), 18. Windows by the Gorham studio also appear in the aisle program. For excellent color illustrations of a Gorham windows closely patterned after English styles, see windows by both Gorham and Heaton, Butler & Bayne, 1910-12, in William E. Van Brunt, Jr., The Windows of Christ Church (Greenwich, Connecticut, 1989), 9-15, 34-5. I am grateful to William Van Brunt for bringing these windows to my attention.

39. ^ The inscription reads "To the Glory of God and in Memory of Jimellen Gottenstrater, the granddaughter of Dr. and Mrs. Hiram W. Evans." Jimellen was born June 21, 1939, and died June 16, 1945. Donald S. McKelvey, An Interpretation of the Sanctuary and Clerestory Windows of Peachtree Christian Church (Atlanta, 1975), 17. The window was painted by Barbara and Dulcima Glasby. I am grateful to Peter Cormack of the William Morris Gallery, London, for information about Glasby and his daughters. I am also indebted to the late Thomas Lyman and Arnold Klukas for organizing the conference Medieval Mania at Emory University which facilitated my inspection of these windows. I am also grateful for help from Kenneth H. Thomas Jr., Historic Preservation Section of the Department of Natural Resources, Parks and Historic Sites Division, Atlanta, Georgia.

40. ^ I am grateful to Rolf Achilles who brought this and a number of important glazing programs in Chicago to my attention. The window is inscribed, "Gift of Mary Welch."

41. ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929. Driskel 1992, pp. 188-93

42. ^ Gabriel P. Weisberg, "From the Real to the Unreal: Religious Painting and Photography at the Salons of the Third Republic," Arts Magazine 60 (Sept./Dec. 1985), 58-63. See also Idem., P. A. J. Dagnan-Bouveret and the Illusion of Photographic Realism," Arts Magazine 57/7 (March 1982), 100-5 and Driskel 1992, esp. pp. 203-20, with discussion of the art of Munkacsy and Tissot.

43. ^ See above, Chapter 5.

44. ^ Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh.

45. ^ Estelle Jussim, Slave to Beauty: The Eccentric Life and Controversial Career of F. Holland Day, Photographer, Publisher, Aesthete (Boston, 1981), esp. 120-35.

46. ^ Hammond 1978, pp. 170-207. A sketch for Hector and Andromache was published by Charles de Kay in "The Renaissance of Stained Glass Harper's Weekly (July 13, 1889), 568. See also Patricia Malfati, "Frederick Crowninshield: A Many Faceted Artist of the American Renaissance. 1845-1918," Masters Essay, Department of Art, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1989.

47. ^ "The Trinity of God, Man, and Nature was central to the nineteenth century universe." Barbara Novak, Nature and Culture, American Landscape and Painting 1825-1875 (New York, 1980), 47. See entire work for the most comprehensive work on these issues, but esp. 34-77 on the concept of the sublime and on the contribution of American geological sciences towards reverence of nature. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen’s recent study of Agnes Northrop’s work is thus most welcome. “Agnes Northrop: Tiffany Studios’ Designer of Floral and Landscape Windows,” in Louis C. Tiffany and the Art of Devotion, Tricia Pongracz, ed. (Museum of Biblical Art with D Giles Ltd, London, 2012), pp. 162-183.

48. ^ Duncan, 1970, fig.40.

49. ^ Sturm 1982, fig. 108.

50. ^ The window is also inscribed "In memoriam, Jason Samuel Bailey and Family" in Roman capitals and L. C. Tiffany, 1921, in cursive script. The partial list of the Tiffany commissions published by Alastair Duncan (Duncan 1980, p. 215), mentions two Tiffany windows of angels. See Duncan 1980, pp. 162-177, and throughout for similar Tiffany landscapes.

51. ^ The architect was Arthur W. Bowditch and the Olmsted Brothers firm designed the landscaping. In 1990 the school buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

52. ^ For the development of this genre, see Kermit Champa, From Corot to Monet. The Rise of Landscape Painting in France [exh. cat., Currier Gallery of Art] (Manchester, New Hampshire, 1991).