City of Paris rotunda in

Neiman-Marcus store, San

Francisco.

Photo: courtesy Peter Talke The past century and a half have wrought radical transformations in many American

City of Paris dome in

Neiman-Marcus store,

San Francisco.

Photo: courtesy

Sanfranman59 institutions. Government buildings, educational institutions, museums, commercial emporia, and private homes have invariably expanded and restructured to respond to new needs and clientele. Some renovations have attempted to preserve the mystique of the old, as exemplified by the incorporation of the 1909 City of Paris department store dome in the new Neiman Marcus's San Francisco store.1 Such transformed buildings, however, rarely preserve the entire context. The interiors and the stained glass programs of religious buildings have been far more resistant to change. Religious buildings often preserve their original setting to a remarkable degree. They present incontrovertible, and one might suspect sometimes even unwelcome, testimony of the centrality of morally inspirational imagery to this age. The museum at the turn of the century, like the religious edifice, was also dominated by what to modern eyes seems a strange mixture of eclecticism, sentimentality, and replicated images, all subservient to the moral imperative of the inspiration of the soul. The objects gathered in both institutions prioritized links to the past, in opposition to the prevailing criteria of modern value, originality and individual expression.2 The images in glass, canvas, or book betray the strengths and limitations of the academic painting of the same century, revealing the beginnings of a bifurcation between didactic image-making and "fine-art" of the present gallery and museum system. To reevaluate these objects reveals the consequences of the past marginalization of certain kinds of artistic expression.3

Stained glass: operating beyond the gallery system

That the field of 19th-century stained glass has been rarely studied from this perspective is largely attributable to the very attitudes that fostered the revival of the medium itself. Both practitioners and patrons saw themselves as continuing a great tradition and, as with any traditional society, saw their specific context as reflecting ineluctably what had always been. The 19th century, however, was very different from the time of the great cathedrals. It was an age of ethnic diversity, global communication, public education, and representative democracies, all phenomena completely absent from medieval societies. Religion as well as government saw itself as serving the needs of an entire population, at least in theory, whereas medieval concepts of state and church were far more grounded in the belief of orderly hierarchies, each with its separate designated duties and privileges. The concept that religious images were mandated as instruction for the illiterate, or that the church had an obligation to proselytize among the underprivileged is certainly a modern idea.4

Modern people and modern images

.jpg)

Unidentified German Studio,

Thomas & John Morgan Studio,

installers, Holy Family, 1876,

Cathedral of the Holy Cross,

Boston. Photo: Michel M. Raguin The post-medieval windows, however, do instruct, or at least they inspire with images designed to present role models to the faithful. This interaction signals one of the most significant differences between 19th-century and medieval images; the relationship to the spectator. In 19th-century buildings, the windows are invariably low and close to the viewer. Spectators are confronted with large, often life-size figures set in a believably "realistic" space. The impact is a personal one. The Apostles surrounding Christ in the Doubting Thomas window or Joseph and St. Anne in the Holy Family window in Boston's Roman Catholic Cathedral [See Appendix], are seemingly believable figures. They are examples to be emulated, and therefore serve a radically different function from that of the medieval image. The saint in the early Middle Ages was one's champion, whose heroic, and usually miracle-strewn life, proved his or her special status before God. The saint was one's patron, not one's model.

Personal concerns imaged for the viewer

What we would now term as the "private sphere," family life, and personal morality, so

Hugo van der Goes, Nativity

from the Portinare altarpiece, 1475,

Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Photo: Web Gallery of Art important to this age began to appear in 15th century. Imagery emphasizing the family life of Christ and the infancy of the Virgin became increasingly popular. Unfortunately the Gospel accounts of Christ's familial life are frustratingly meager in the details important to the laity. The laity therefore turned to the apocryphal texts and mystical revelations, such as those of Brigitte of Sweden concerning the birth of Christ, to fill out the bare bones of the stories. The now common depiction of the infant Jesus lying naked on the ground in a glow of Divine radiance, while Mary kneels in adoration is not a biblical nor even a medieval tradition; it is Brigitte's vision.5 One of the important innovations of the late medieval period was the theme of the Holy Kinship , a representation of the extended Holy Family centered on Jesus' grandmother, St. Ann. Dissemination of these themes reached a broad population because of the development of the graphic arts, the woodcut and the engraving.

Post-medieval patronage by a diverse public

The enhancement of the content and spectator relationship as a primary definition of artistic value grew out of this more diversified and broad relationship. No longer was the artist simply satisfying a single patron or class of patrons, such as a reigning monarch or a monastic foundation. Post-medieval patronage took place in a broader climate and for a more heterogeneous public, a situation that encouraging a corporate response on the part of artists. Artists formed academies of art to supersede the older craft guilds. In the place of craft-based distinctions, the academies of the 17th and 18th centuries developed a hierarchy of genres, that is, a hierarchy of the subjects depicted, with historical and religious painting at the apex.6 The older "mechanical" arts became "liberal arts" only by functioning in ways that paralleled the methods of philosophy or rhetoric. Art achieved a higher or lower status according to the success with which it engaged the spectator's intellect and emotions to educate and to persuade. In this context, writing about art became an inevitable aspect of its function. Produced in an atmosphere of discussion of principles, art experienced its critical reception through public exhibition, academic discourse, and journal and newspaper reviews.

Admiration for the Renaissance

Nineteenth-century stained glass painters were a part of this transformation of craft. They were eager to bring the value of their product beyond "mere decoration," to note Charles Winston's characterization, by identifying with the prevailing academic definitions and models of great art.7 They entered the area of artistic debate via discourse, exhibition, and published reviews. They sought their models in the art of painting, the established major field of production. The glass painters admired medieval art for its decorative brilliance, but for the image itself, the art of Europe from the 15th through 16th centuries provided the most appropriate themes and figural models. Their reliance on art of these eras reflected the bias already effective in their patrons. The foundation of the great 19th-century public collections was the art of the 15th through 16th centuries from the Lowlands, Germany, and Italy. Ludwig of Bavaria purchased the Boisserée brothers' collection of German and Lowlands paintings in 1826 as the core of what we now know as the Alte Pinakotek in Munich. Among the earliest paintings given to the National Gallery of London were those of Lowlands and the Italian Renaissance, many of these gifts of Queen Victoria. The idea that the high point of religious expression had been achieved during this period dominated 19th -century American criticism as well. In 1895 the Clara Erskin Clement connected the developments in American religious painting to the undisputed model: "it was not until the early Renaissance that men began freely to express on canvas and in marble, each one his highest conception of what Christ was like; and during the few centuries following that period the pictures that realize our ideals of religious paintings were produced."8

Dissemination of models

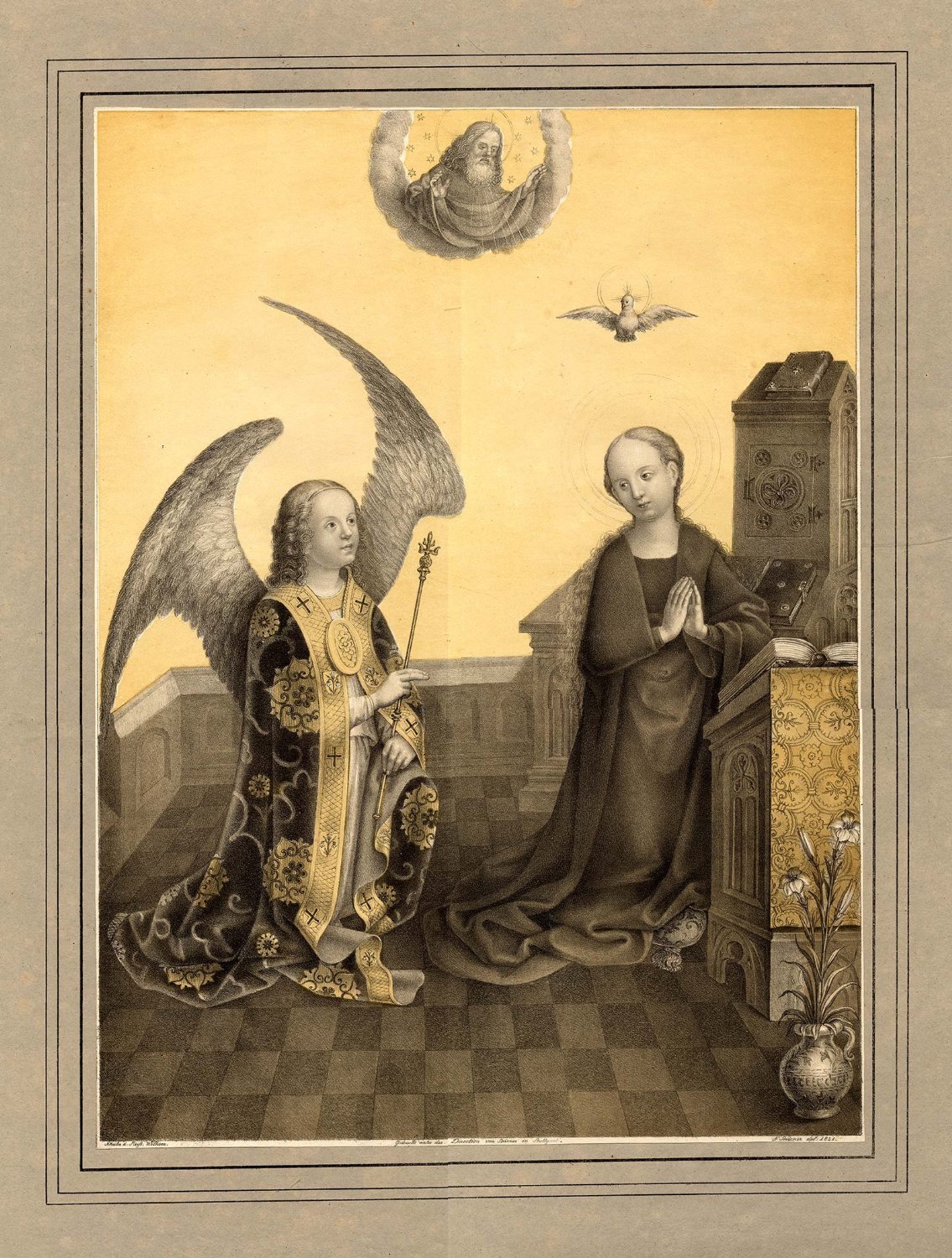

Johann Nepomuk

Strixner, Annunciation, after

follower of Stephan Lochner?,

lithograph, 1821.

Image: Amazon.comBefore photographic reproduction of works of art, the means of disseminating these models

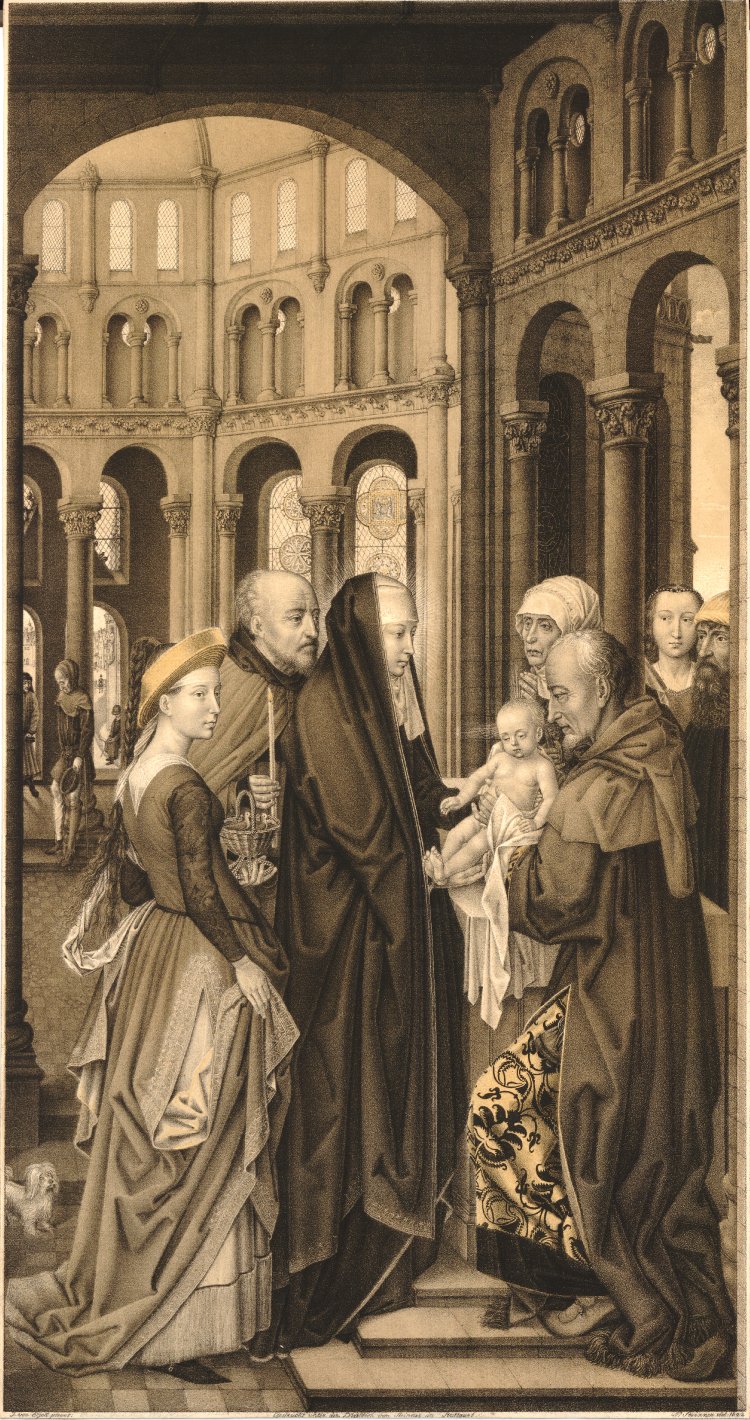

Johann Nepomuk

Strixner,

Presentation in the

Temple, lithograph,

1822, after Rogier van

der Weyden, left wing

of the Columba

Altarpiece, 1455, Alte

Pinakothek, Munich.

Photo: courtesy British

Museum Collection

online, Galerie des

Frères Boisserée,

no.1860.0114.161 profoundly influenced their reception. The glass painters and their patrons may have seen Rogier van der Weyden's Three Kings (or Columba) Altarpiece in Munich, or Raphael's cartoons for the Vatican Tapestries in London, but if they were to refer to accessible images to

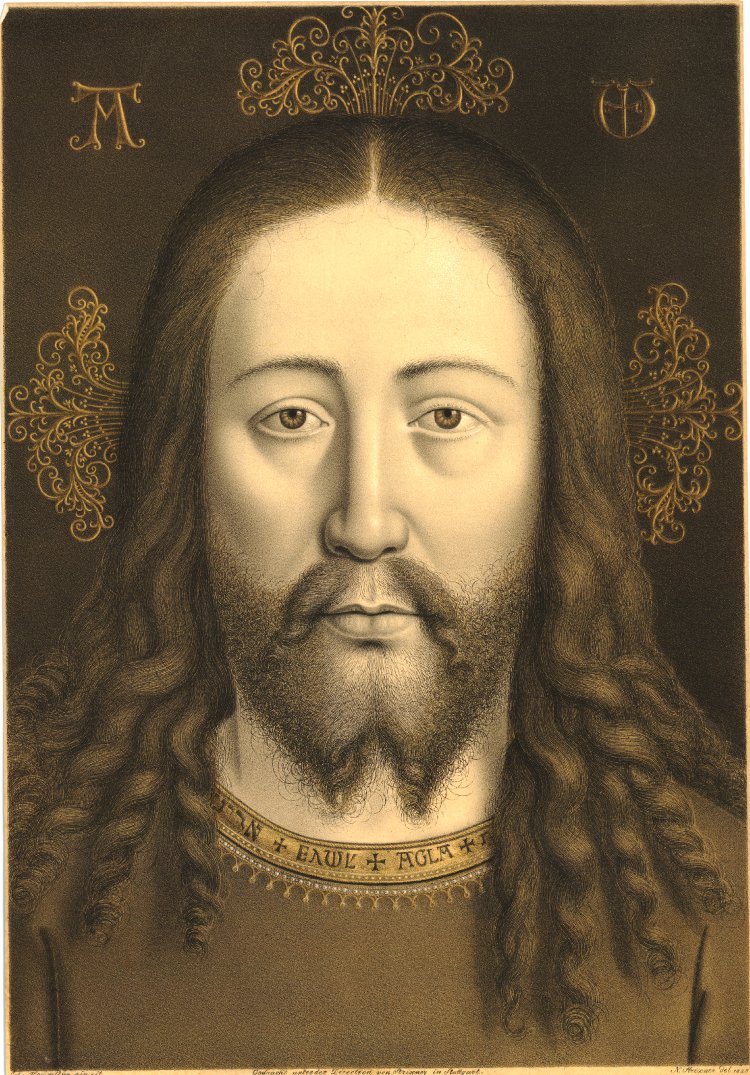

Johann Nepomuk

Strixner, Head of Christ:

Salvato Mundi, lithograph,

1825, after painting

previously attributed to

Hans Memling 1438,

Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

Photo: courtesy British

Museum Collection

online, Galerie des

Frères Boisserée,

no. 1860.0114.206jog their memories, the images would have been prints after these subjects.9 For most of society, engravings and lithographs after the great masters, such as the series of prints that reproduced the Boisserée brothers' collection published in 1822, were often the only visual references.10 The purpose of such printing was didactic, helping to transfer the values of the past into the present.11 The Düsseldorf Society for the diffusion of "good religious pictures" was typical in its systematic reproduction of a wide variety of prints after paintings.12 The replica of a masterwork produced by a 19th century hand and the "new" window or wall painting inspired by the great master therefore became virtually identical, allowing the artist and the patron to ![]()

After Jan van Eyck,

Savator Mundi, 1434, Alte

Pinakothek, Munich.

Photo: courtesy

blogs.privet.ru/user/

glushcenko_valeriy/

114935882believe that the ancient model had been reproduced in the modern world with total fidelity. For example, the lithograph after the Head of Christ by a follower of Van Eyck in the Boisserée brothers' collection, transforms the angular proportions of the face into a fleshy and softened image identical to the depictions of favored by Nazarenes such as Overbeck or Cornelius, and later ubiquitous in 19th-century windows.

Plaster casts: the essential stock of art museums

To understand the climate in 19th-century America concerning issues of art, religion, and

Museum of Fine Arts, Copley

Square, Boston, 1890-1901, Detroit

Publishing Company.

Photo: Library of Congress

Online Catalogreplication for the public, we may turn to the foundation of our public institutions of art.13 The great halls of the Metropolitan Museum, founded in 1870, were once filled with plaster casts.14 In fact, in the 1890s the Museum's director was engaging in the production of casts "just as good as those brought from Europe (but) at a cost much less than that paid for the imported ones."15 The first acquisition proposed for the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston was a collection of casts and photographic copies.16 When Wellesley College first dedicated its school of art, the walls were hung with 19th-century landscape paintings and the floor populated with replicas of classical

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

Classical Court, 1890-1901, Detroit

Publishing Company.

Photo: Library of Congress

Online Catalogsculpture.17 In 1906, H. G. Wells, after a trip to America, wrote that he retained of Wellesley a vivid memory of "a sunlit room in which girls were copying the details in the photographs of masterpieces."18 Martin Brimmer, the founding director of Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, delivered the dedicatory address for Wellesley's new building. His argument concerning the value of art places these practices in context.19

Inspiration from Greece, Holland, and France in Boston

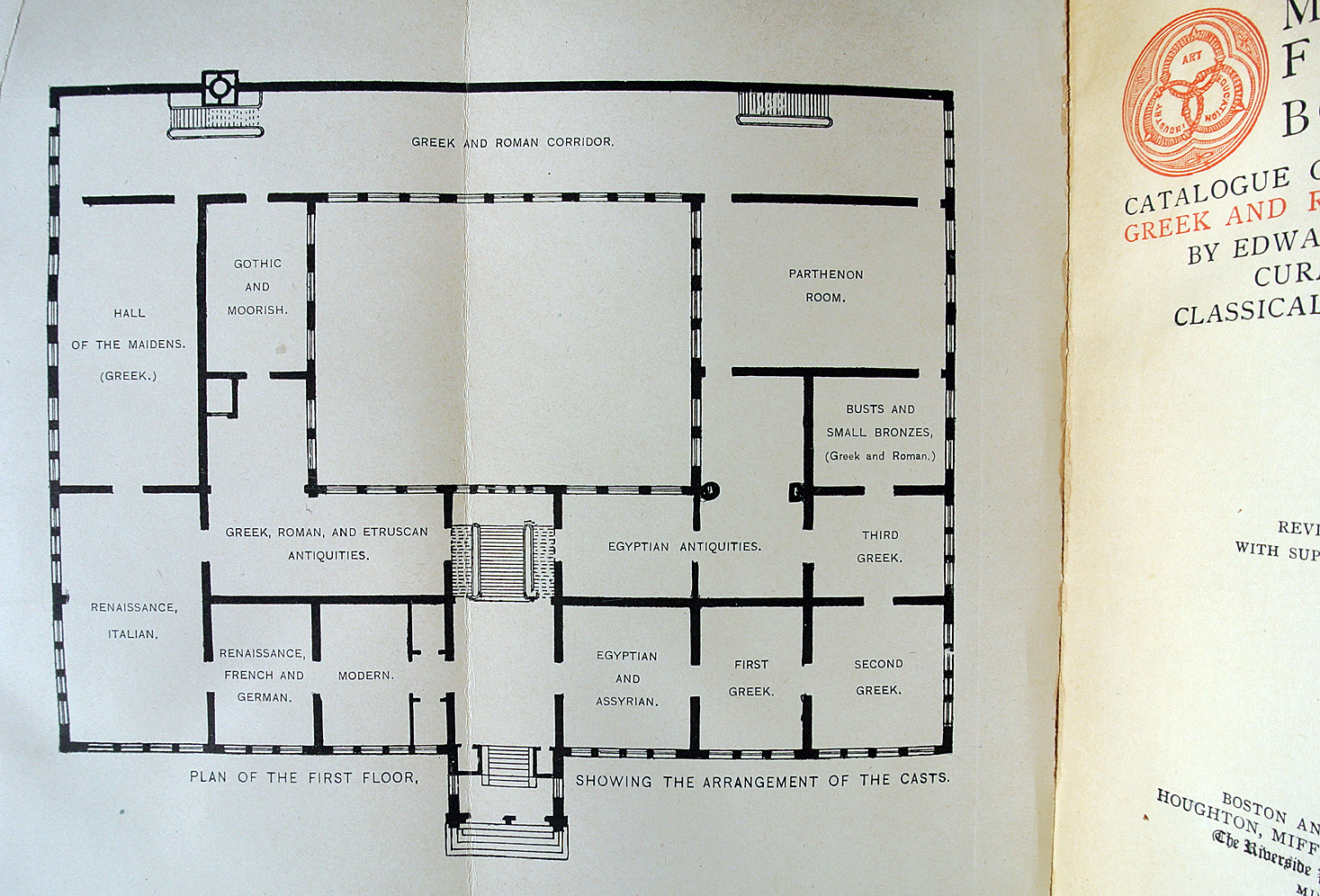

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Floor plan

showing the arrangement of casts, Edward

Robinson, Curator of Classical Antiquities,

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Catalogue of

Casts, Part III, Boston:

Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1905

Brimmer's words define for their time the perception of the sacred nature of art and the efficacy of replicated images to participate in this holy process. Art for Brimmer was an indicator of the moral fiber of a nation, for great art cannot be produced by an ignoble society. "It demands a high national pride, a past that is cherished with pride, a future bright with hope." Brimmer qualified for his Wellesley audience three great moments in the history of art, Classical Athens and the sculpture of Phidias, 17th-century Holland and Rembrandt, and the period from the Restoration to the 2nd Empire in France represented by the art of Delacroix , Rousseau , and Millet. America was capable of art on the level of these past

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

Renaissance Room, 1890-1901,

Detroit Publishing Company.

Photo: Library of Congress

Online Catalogexamples, in fact, the possibilities were even richer since the American society was freer. The Athenians owned slaves, the Florentines employed mercenaries, but in America the leisure for art was being gained for contemporary society by machines. Indeed "mechanical reproduction (was) bringing, in some form, the finest work near to every home."20

Brimmer's evaluation of Jean François Millet is particularly revealing for its intermingling of judgments of aesthetics, civic responsibility, and religion. He informed his audience that Millet's "youth was nourished on two books which are in themselves an education, his Bible and his Virgil." A great admirer of the artist, as the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts attests, Brimmer elucidated the meaning of Millet's landscape. "It is in truth a religious work: as reverent as Botticelli's angels and coming nearer than Botticelli could come in his day to the 'secret of the painful earth.'"21

The De Young Museum, San Francisco

The ideas were ubiquitous. The founding of the first fine arts museum in San Francisco embodied the sentiments that Brimmer had conveyed to Wellesley women: the values of education, moral guidance, and the importance of the past. The institution, renamed in 1921 the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, reflected the aspirations of its founder, Meichel H. de Young, publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle.22 De Young had served as a National Commissioner at large for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago of 1893, an experience which was a catalyst for his organization of the Californian Midwinter International Exposition in Golden Gate Park of 1894. The Chicago Exposition had emphasized classical models and, in contrast, the exhibitors in San Francisco were asked to adhere to exotic themes. After the Exposition, de Young succeeding in establishing a permanent museum which was housed in the Exposition's Egyptian-Revival style Fine Arts building. Sphinxes are still prominent sculptural decorations at the entrance of the museum building today. The objects displayed were acquired for the most part from the exhibits at the Exposition and the open admissions were financed by the Exposition profits. The founding patrons conceived of the museum as an institution that served the entire community; the liberality of admission corroborated the public service goals.

The collections grew in these early years through de Young's personal support. Like other California collectors, such as Leland and Jane Stanford, de Young's interests were eclectic and ranged as much to the "history of man" as to what was considered the fine arts. He purchased, for example, John Vanderlyn's Marius Amidst the Ruins of Carthage which became the core of the impressive American art collection of the museum, but he also acquired arms and armor, objects of natural history such as birds' eggs and sections of tree trunks, works of South Pacific and American Indian cultures, as well as copies of Old Master paintings.23 An enthusiastic public response greeted the educational direction of the museum, with six thousand visitors on a Sunday a normative expectation.24 De Young's will set up an endowment whose income would support "purchasing curios and exhibits."25 The departure from this early eclectic and public educational thrust came less than a decade after de Young's death in 1925. Walter Heil, a native of Darmstadt, Germany, was appointed director in 1933 after serving six years as chief curator of the collections at the Detroit Institute of Arts under another German-born arts administrator, William R. Valentiner.26 Heil, whose appointment reflected the changing taste of the museum's supporters, shifted the acquisition policies of the museum from the wide-ranging policies of its founder to the more modern thrust of exhibiting objects, exclusively of the fine and decorative arts.

Stanford University Museum of Art

SM.jpg)

Leland Stanford Junior Museum,

Stanford University, c. 1900.

Photo: California Historical Society

Collection, 1860-1960,

call no. CHS-2620The same evolution is evident in the Stanford University Museum of Art, an even more compelling example of personal and public attitudes.27 Leland Stanford, governor of California and United States Senator, had amassed enormous wealth as one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad. In 1884, after the death of their only child, Leland and his wife Jane Lathrop Stanford decided to found a university in his memory.28 In 1891 the Leland Stanford Junior Memorial University was opened, and three years later the Museum. Stanford's museum rivaled in size the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, both founded more than two decades earlier. The acquisitions of the museum were supervised by Jane Stanford who

Leland Stanford Junior Museum,

Stanford University, after 1906

earthquake. Photo: Stanford U

Archives GP-14794-museumconsciously attempted to continue the precocious collecting interests of her son. Leland Stanford Junior had been tutored by the director of the Metropolitan Museum, Luigi Palma de Cesnola, excavator of antiquities on Cyprus. Cesnola introduced him to Sir Philip Cunliffe Owens, director of the South Kensington Museum, London, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum, an institution conceived with a strong didactic structure and an emphasis on the applied arts.29 The impressive collection of antique pottery from Greece and surrounding areas was heavily damaged in the 1906 earthquake.

The art museum at the turn of the century rested on the precept that art was a means of understanding the culture of the past. The objects were selected, evaluated, and very often displayed to reflect this contextual social bias. Brimmer expressed this presupposition when he suggested to his Wellesley audience that to view Phidias was to understand Athens, or to see Rembrandt was to see Holland. Great artists do not express their personal ideas, according to such a view, but the thoughts that "they share with the society in which they live."30 If such a value system applies to the fine arts, it is easy to understand how archaeological collections, grave goods, native-American artifacts, or objects of dress and utility from the Far East, might also share this ability to express the mind of a culture. Thus, the eclectic nature of the first art museums becomes much more comprehensible. On a trip to Europe in 1883, young Leland acquired examples of Greek vases, Egyptian sculpture, Roman glass, and Early Christian funerary art.31 During the formation of the Museum Jane Stanford bought a number of large collections that furthered this direction as well as branching out into Chinese and Japanese art. But the collections were comprehensive, including Native American pottery, baskets, and stone implements as well as carvings, and Chinese and Japanese armor and weapons as well as lacquer work and screens.32

From residence to museum

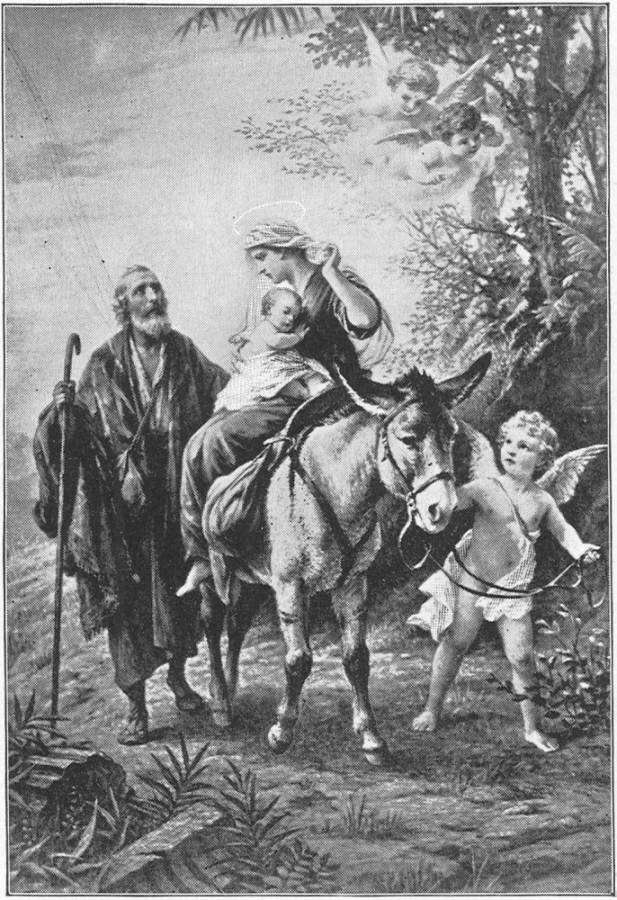

J & R Lamb Studio,

Flight into Egypt (after

Stanford University cartoon)

1908-1910, First Presbyterian

Church, Orange Texas.

Photo: J & R LambThe Museum's holdings expanded through the transfer of paintings that the Stanfords had

Bernard Plockhorst,

Flight into Egypt, after

Henry Turner Bailey, The

Great Painters' Gospel,

1900, pl. 27collected for their private residences in San Francisco, Palo Alto, Washington, and New York. The type of art collected paralleled the decisions made for the decoration of churches of this time. Landscapes, including works by Albert Bierstadt, Norton Bush, and Thomas Hill, were of enormous importance.33 An expanding country that saw the railroad not as defiling wilderness but as a means to integrate God's grandeur into civilization developed a great passion for the landscape painting. Contemporary European artists such as Bouguereau and Gérome were in demand. Taste tended to favor sentimental genre scenes with titles such as The Sick Mother, Family Love, You Mustn't Touch (or, The New Arrival), or Roman Flower Girl. Similar human interest themes would be the subject of window in the University’s chapel, such as The Flight to Egypt after Bernard Plockhorst.34

Like other collectors of the time, the Stanfords purchased copies of great masterworks. Jane Stanford had viewed Raphael's Sistine Madonna while visiting Dresden with young Leland and in 1890 had it copied for the Stanford Museum and for the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Sacramento.35 She was not alone. Copies abounded, in stained glass as well as canvas, from modest Currier and

Currier & Ives, The

Sistine Madonna (Madonna

de San Sisto), 1877-1894,

after Raphael, 1512,

Gemäldegalerie Alte

Meister, Dresden, private

collection.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Ives prints to lavish examples by the Tiffany studios.36 Jane Stanford had previously acquired a copy of Raphael's Madonna of the Chair which was photographed by Eadweard

Leland Stanford Junior Museum,

Stanford University, Entrance lobby.

Photo: Stanford U. Archives Muybridge in their San Francisco house in 1878.37 In 1881 she purchased a bronze copy of the Farneze bull, which she at one time installed in the main lobby of the Stanford Museum. Walter Miller, functioning as the museum's early curator requested the acquisition of stereopticon views illustrating Greek sculpture to "supplement the collections."38 In 1900 and 1901 Jane purchased a large collection of replicas from a dealership in Florence, including copies of Andrea del Sarto's Holy Family (Madonna of the Harpies), Titian's Flora, Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch and Holy Family, Murillo's Madonna and Child, and Correggio's Adoration of the Child.39 In 1902 after a trip by Mrs. Stanford, a series of reproductions of Egyptian artifacts painted on canvas arrived from Luxor.40 Photographs of the museum lobby in 1905 show the installation of copies of Renaissance and classical sculpture, the head of the marble David of

Bedroom of George Vanderbilt,

designed before 1895, Biltmore,

Ashville, South Carolina.

Photo: Biltmore websiteMichelangelo, the head of the Apollo Belvedere, and numerous Greek models. We forget that the “collecting” of the replicated images was near universal. Similar to the Stanfords, but domestically, George W. Vanderbilt would decorated his palatial home of Biltmore furnishing many rooms, including his bedroom, with reproductive prints of European paintings.41

Altered museums but intact houses of worship

The museums have changed. Indeed, even the buildings that once housed the collections, such as the first Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the original fair building that became the de Young Museum, and the pre San Francisco earthquake structure of the Stanford University Museum have either been lost or transformed beyond recognition.42 In many ways the churches built by the patrons of this era remain time capsules preserving the ideas concerning art, public service, and morality that were the foundations of our museums. The images employed in these churches display a belief in the moral value of art and the ability of replicated masterworks to transmit to the present the cultural values of the past.

Stanford University’s Memorial Church and Christ’s life as exemplar

.jpg)

Stanford Memorial Church, front,

Stanford University, 1898-1903.

Photo: Historic American Buildings

Survey Online (Library of Congress) To explore the Stanford University Memorial Church[See Appendix] is to become

Stanford Memorial Church, rear,

Stanford University, 1898-1903.

Photo: Historic American Buildings

Survey Online (Library of Congress) transported to the time of the university's founders. Jane Stanford conceived of a University Chapel as a memorial to her husband, deceased in 1893. Following their joint theology, she constructed the church as a non-sectarian homage to the moral principles of religion.43 In a letter rejecting a proposed appointment to the University in 1896, she explained that "both Mr. Stanford and myself, have firmly resolved that no professor shall be employed in the University who would preach denominational theories of religion. We wish the simple religion of Jesus Christ and His beautiful life held up as an example worthy for all to imitate."44 Christianity, as seen by the Stanfords, was based on the human endeavors of the person of Christ, and therefore was not exclusionary. The "Creed" simply encompassed the virtues described in the Sermon on the Mount (Mat. 5: 1-12). It is significant that Jane Stanford's collecting enabled her to see the values, if not the form, of Christ's example in the art of Egypt or the Far East, thus in all world religions.

Architecture and patronage of Stanford’s Chapel

The style and decoration of the building were profoundly eclectic. Designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, the successor firm of H. H. Richardson, the building shows many similarities with Richardson's most notable ecclesiastic structure, Trinity Church in Boston, discussed earlier. The facade is a Romanesque design dominated by three rounded arches. A wide but short nave leads to a broad crossing crowned by a circular dome. A typological relationship resonates between the interior mosaics, most generally of Old Testament themes, and the major windows which present scenes from the Life of Christ. Both the mosaicist, Maurizio Camerino of the Antonio Salvati studios, Venice, Italy, and Frederick Stymetz Lamb, director of the J. & R. Lamb Studio, New York, worked closely with Jane Stanford.45

There is no question that the patron played a decisive role in the selection and execution of the architectural and pictorial elements of the building.46 Site-specific doctrinal and sociological statements appear, such as the emphasis on women and human relations. Women appear with unusual frequency in both the mosaics and window decoration. Jane Stanford is reported to have wished to show "their equal participation in the history and benefits of religion."47 Her correspondence concerning the fabrication of the mosaics, installed after the windows, speaks to this commitment to the equality of the sexes. "I have concluded to place mosaics to correspond with the colored glass windows in order to decorate this plain wall. You will notice each double window holds the single figures of a man and a woman and I wish you to select also a single male and female figure from the Bible for your mosaic from the Old Testament."48 Particularly significant for our inquiry, however, is the clear admission that all of the major windows replicate paintings by artists such as Deger, Dietrich, Doré, Hofmann, Holman Hunt, Murillo, and Plockhorst that had become standard "icons" of Christian instruction. The glass program corresponds to the popular reproductions of Renaissance paintings in the art of Italian mosaicists at this time.49 (See Appendix for Stanford's stained glass program.)

Religion in public

Stanford Memorial Church,

interior towards altar, Stanford

University, 1898-1903. Photo:

Historic American Buildings Survey

Online (Library of Congress) The reverence for religious and moral principles, articulated by the program of the  -N1.jpg)

Stanford Memorial Church, altar

area, Stanford University, 1898-1903.

Photo: Eric Chan church, was a standard aspect of American society at the turn of the century. Stanford wrote as much in 1892 in a letter to David Jordan, President of the University, approving appointments of several professors. He went on to reveal his thoughts on "true human civilization, (being) pretty well satisfied that such a civilization will never exist without a belief in the immortality of the soul and in the beneficence and justice of all the laws of the Creator. . . Intellectual and moral development alone are not sufficient to insure true civilization."50 A newspaper columnist had earlier quoted similar views from Stanford. "

. . . I think that whatever makes this world happier enlarges the moral strength of men. I believe in the immortality of the soul, and that as we live here our progress will be (in eternity); that if we consider our neighbor and the law of kindness we shall be fit to be further advanced toward the enjoyment of another state, that the two states, that of the earth, and the future, belong to each other. I don't want any sectarian teaching in this University, but I do

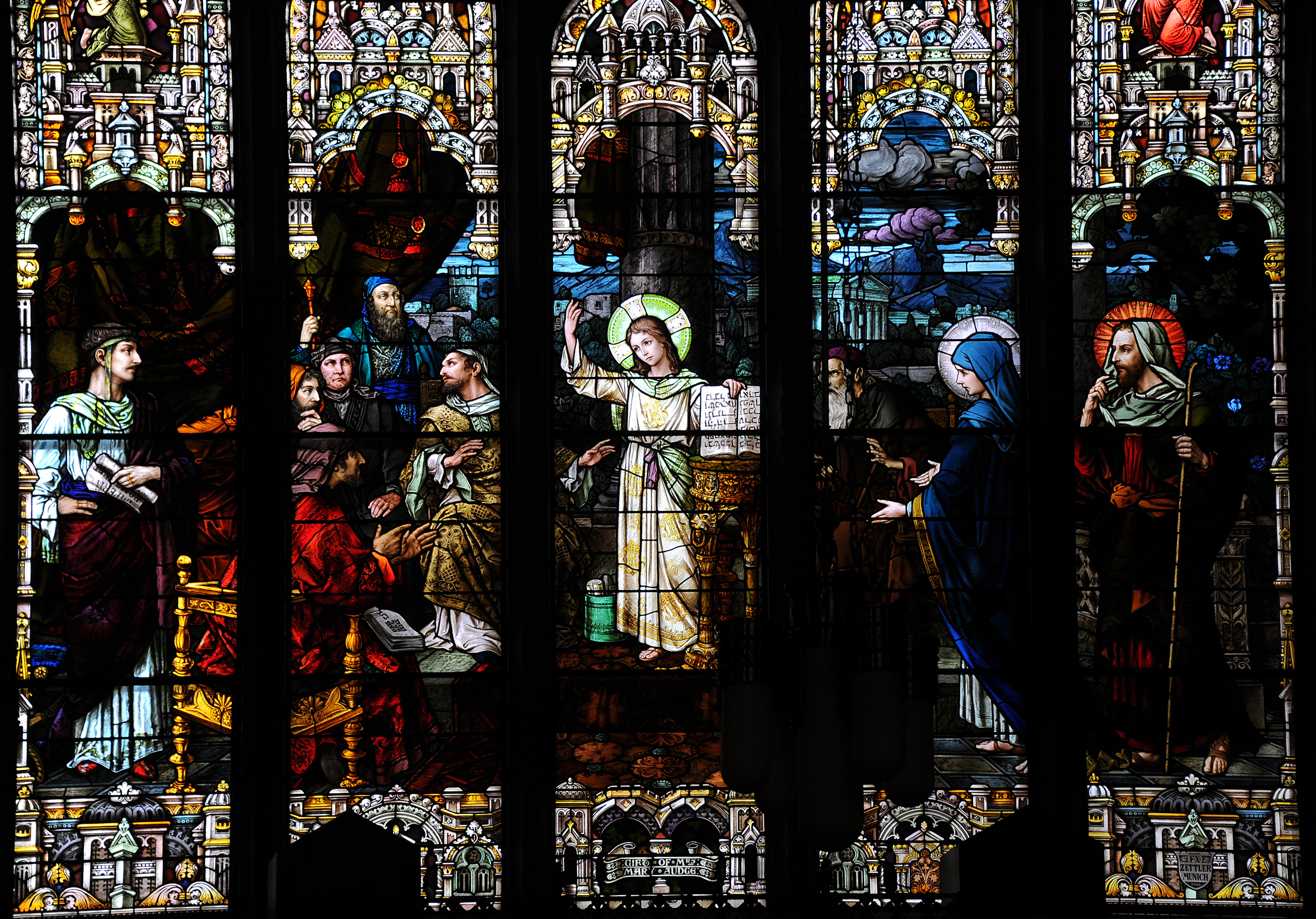

J & R Lamb Studios, Boy Jesus

in the Temple and Baptism of Christ,

Stanford Memorial Church, Stanford

University, 1898-1903.

Source unidentifiedwant the law or moral obligation taught. I believe there is a harmony and a system all through creation; that the earth and the heavens are built on an intelligent plan and that the finding of this plan will make the earth yield better to men's wants...

The world, in my opinion, can be indefinitely advanced by having for its moral basis the teachings of Christ, and by diversifying avocations (occupations), until mere labor is made, by art and understanding, our highest privilege."51

Leland and Jane Stanford's articulation of purpose is typical of their generation and status. What a late 20th-century audience would see as separate issues, that of the previous century saw linked. It is telling that in 1939 the Heinz Memorial Chapel of the University of Pittsburgh could continue to incorporate explicit references to Christian saints such as St. Francis of Assisi as well as imagery from the Gospels to accompany themes from American history and literature.52 Like the Stanfords, Americans of this era would still articulate religious sentiment as not only compatible with financial success, but at the very heart of their ability to function with effectiveness as business and civic leaders. At the turn of the century it was rare for any individual to be "unchurched." A review of Harvard College class reports is revealing of this. In the 1870s the graduation statistics listed the religious views of the class quite explicitly; in 1900, the issue of religious affiliation was a part of a larger group of statistics, but still quite public.53 Only in 1886 did Harvard substitute for "daily prayers" a daily "religious service" which students were not compelled to attend. This was the first instance when compulsory chapel was abandoned by any American college, and it did not fail to cause concern about the future of Harvard.54 The Stanfords remained unaligned with any one established denomination, although they had a pew in the Presbyterian Church in Menlo Park, California in 1890, but supported all religious commitment. The consecration ceremony for the church was appropriately interdenominational and ecumenical, with prominent place given to a rabbi.

Movies and windows

D. W. Griffith, Intolerance,

1916, image of Christ,

Photo: acinemahistory.comPerhaps one of more important, however little appreciated, testimonials to 19th-century imagery of this type is its influence on the early history of film. D. W. Griffith's Intolerance was produced in 1916 as the film maker's protest against the slaughter on the battlefields of World War I. He set four themes against one another, cutting back and forth throughout the film to establish visual and thematic parallels: a contemporary couple beset by unemployment, urban vice, and self-righteous reformers, the fall of Babylon orchestrated as a conflict of religious ideologies, the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre and the 16th-century campaign against France's Huguenot (Protestant) minority, and Christ's persecution and death. An explicit labeling device is a text projected when the theme of Christ is introduced. In showing the veracity of the scenes in Nazareth and Jerusalem, such as Christ "sitting down to eat with sinners" Griffith cites the authority of J. James Tissot. Tissot is a 19th-century painter increasingly studied for his intersection with Impressionist painting. The best known of Tissot's accomplishments at the turn of the century, however, may be his volumes of illustrations of the Old and New Testament. Tissot's The Life of Our Savior Jesus Christ, in three volumes published by The Werner Company may have been the source of that Griffith used.55 Despite contemporary conception of the value of narrative in religious imagery, we do well to consider its general acceptance at this time, even as a major reference for one of the most brilliant and progressive directors of the cinema.

Publications and sources

The reliance on this literature of popular imagery continued through the 20th century. Even the studios of the Second Gothic Revival, discussed later, stylistically very different from the opalescent realism of J. & R. Lamb, still used the same sources.56 The situation of the Charles J. Connick Studio of Boston may serve as a typical example. The studio's library contained an abundance of great master reproductions seemingly identical to printed sources from which Lamb found his models.57 The library consisted of over 1,000 separate entries, often multiple volume works, such as encyclopedias and journal subscriptions. The major scholarly publications on glass painting by authors such as Merson, Westlake, Drake, Delaporte and Houvet, Magne, Arnold and Saint are found.58 The iconographic references are even more impressive: numerous versions of the Bible, prayer books, missals, indexes to saints' lives, and church symbolism such as Anna Jameson's Sacred and Legendary Art, Butler's Lives of the Saints, Adolphe Napoléon Didron's Christian Iconography or the History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages (London, 1863), William Caxton's The Golden Lives of the Saints (London, 1900) and Durandus' The Symbolism of Churches (translated by the prominent Ecclesiologists, Neale and Webb). Most revealing, however, are the 19th-century publications of collections of religious images similar to the kinds the formed the basis for the imagery produced by Lamb for Jane Stanford.59 Frederic Farrar's Story of a Beautiful Life Illustrated and (anonymous) The Light of the World or Our Savior in Art (London, 1899), as well as the Old and New Testament collections after Tissot were well used and marked by Connick.

Renaissance as well as 19th-century works illustrated many of the books owned by the studio. Louis Veuillot's, Jesus of Nazareth (Paris, 1877), contains the complete gamut of sources, from Byzantine icons, Early Christian sculpture, Raphael's tapestries, prints by Goltzius, Dürer, and Memling, to 19th-century favorites such as Doré. W. Shaw Sparrow's, The New Testament in Art (London, n.d.) is illustrated with photographs of works of Rembrandt, Tiepolo, Rubens, Burne-Jones, Ford Maddox Brown, Holman-Hunt, Millais, and Bouguereau, among many others.

Patrons' desires

Aristotle, designed

by Mrs. Woodrow Wilson,

originally in “Prospect,"

the residence of Princeton

University's presidents.

Photo: unidentified

newspaper clippingThe influence of the Renaissance continued unabated throughout all of American glazing, whether thematically in subject matter, conceptually as "the" means of rendering figures in space, or as furnishing models for exact duplication. Often the patron requested a replica of the admired model, such as we have seen in Jane Stanford's commissions from Lamb. The Gloria in Excelsis window installed in 1905 over the altar in All Saints Church, Norristown, Pennsylvania, presents "faithful copies of Fra Angelico's Angels of the Great Tabernacle, now in the Uffizi Palace, in Florence."60 The creators of the church booklet obviously saw the source of the image as a matter of pride, and the window's location in the most prestigious area of the church confirms the status of both new and old image. Even windows in domestic settings demonstrated the acceptance, even desirability, of such replication. The first Mrs. Woodrow Wilson designed a window depicting Aristotle for her home, "Prospect," at that time the residence of Princeton University's presidents. It is a ten by five foot window showing a large Renaissance arch framing an image of Aristotle modeled after Raphael's image of the philosopher in the School of Athens fresco in the Vatican apartments.61 The Greek inscription below the figure is taken from Aristotle's Ethics, "Human good is the activity of the soul in accordance with virtue." The patron in this case is viewed as the designer, simply for the selection of images from the past.

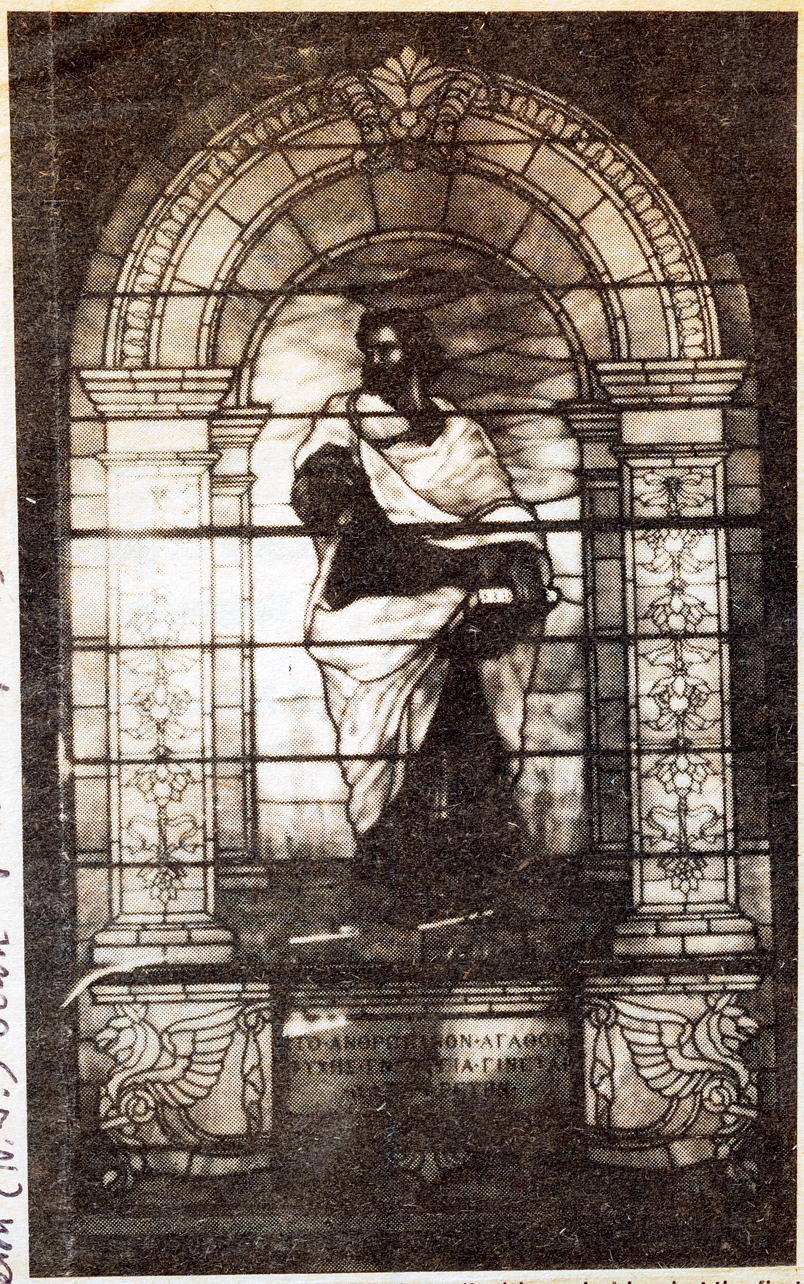

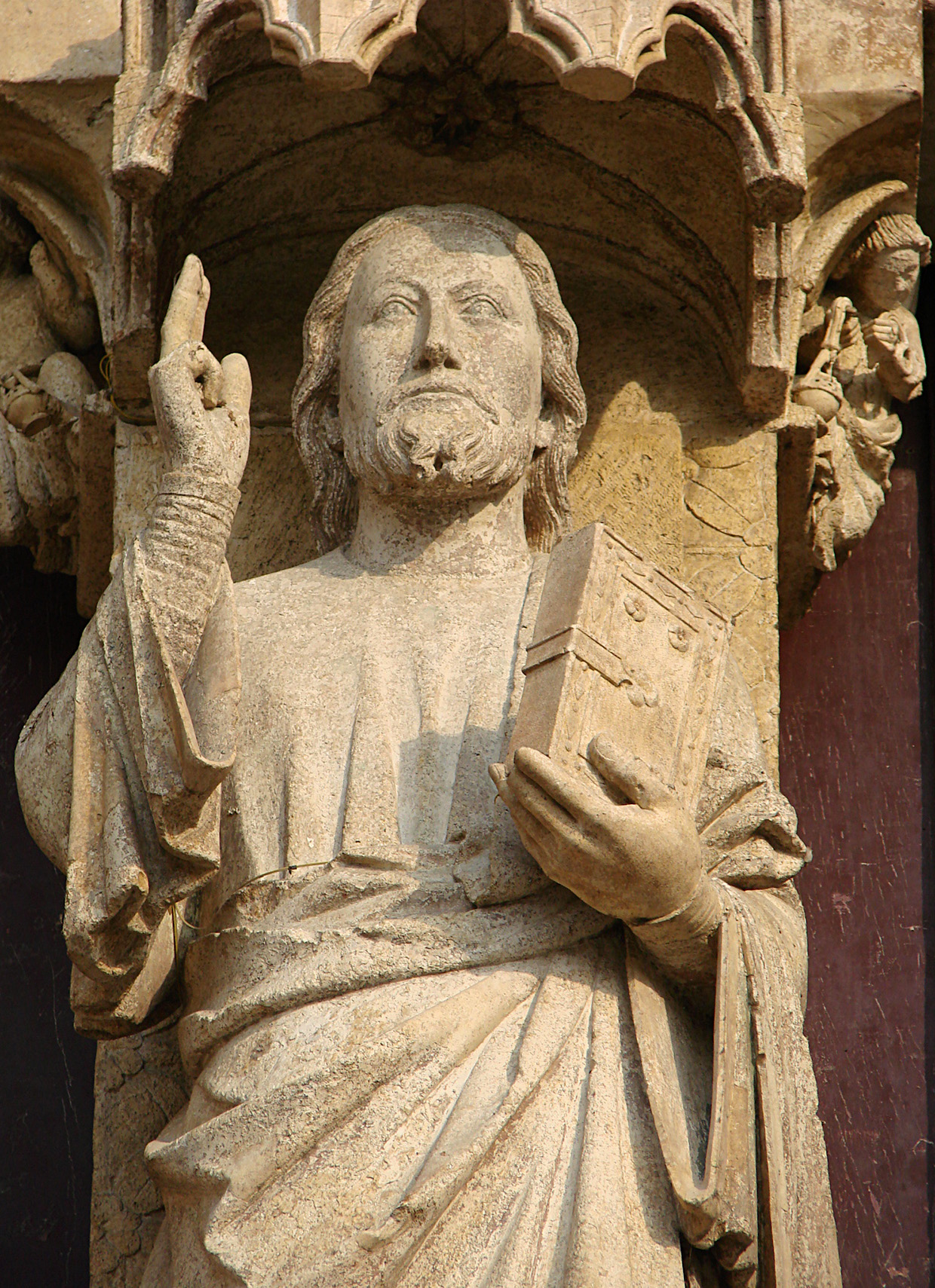

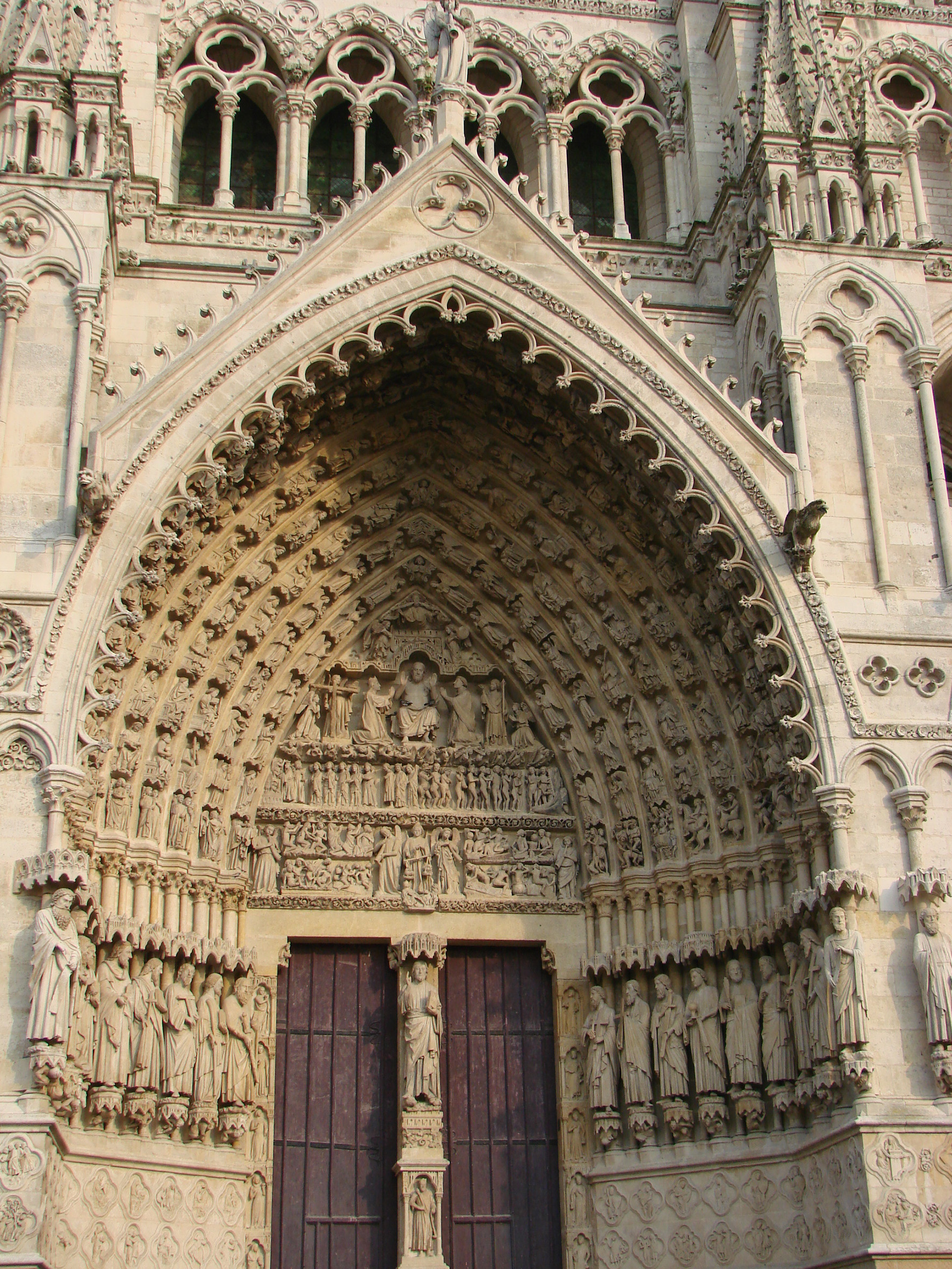

John La Farge, Phillips Brooks and the Beau-Dieu of Amiens

The conflux of patron, artist, and shared views of past models operated even for the most

John la Farge, Christ Preaching,

1883, Trinity Church, Boston.

Photo. Jeffery Howeprestigious commission. The long-admired west window of Trinity Church in Boston designed by La Farge exemplifies this issue. In 1893 Siegfried Bing, visiting America to survey for France the state of the arts at the World's Columbian Exposition observed that "all marveled at the large stained glass window whose astonishing brilliance surpassed in its magic, anything of its kind created in modern times."62 John La Farge had been awarded the commission in 1880. The long process of his experiments with his opalescent style, discussed earlier, occupied his energies so that it appears that he only began to plan the window seriously in 1883, and produced a small sketch

Cathedral of Amiens,

west façade central portal,

Beau Dieu, 1220-30.

Photo: Vassilincorporating Early Christian architectural motifs. His original multilevel design included two narrow Gothic arches that housed figures. His pencil note next to the image, "Perhaps better empty without figures" suggests that he wanted them removed.63 Phillips Brooks, Trinity's charismatic rector, presumably, did not.64 Biographers of the artist have assumed that Brooks suggested the sculpture of the Christ of Amiens as the basis for the window. La Farge then replaced the multilevel design and set the Beau Dieu image of Christ in the central lancet and sections of an arcade at the sides. Whether Brooks or La Farge initiated the use of the image is less important than the reality that an accepted model was known to

Cathedral of Amiens,

west façade central portal,

1220-30. Photo: Vassil both patron and artist. In fact, I would suggest that this image of the central portal figure from the 13th-century facade of Amiens cathedral had become one of the near universal references for its late 19th-century audience. Its status reflects the context of the era’s canon of great works of art, communicated through photograph, engraving, and literary description. 65

In Boston these judgments were propagated through a small but passionate and cultivated set that included the patrons of the windows at Harvard and Trinity Church. One of the chief figures in this intersection of art, culture and religion was Charles Eliot Norton, from 1874 through 1899 first professor of the history of art at Harvard.66 In 1855 he had begun a long and productive friendship with John Ruskin, the extraordinarily prolific writer on Romantic

Beau Dieu of

Amiens, frontispiece,

Frederic W. Farrar, The

Life of Christ as

Represented in Art, 1900.painting, architecture, and religious feeling.67 Ruskin did not invent the importance of the Amiens Christ, but made it an ineluctable part of any cultivated Christian's awareness. His Bible of Amiens describes the sculpture as the true key stone of both art and faith. He published the book in stages, the description of the cathedral's sculptures separately in 1881 to facilitate its use as a guide book.68 Ruskin hearkens back to other authority, citing Viollet-le-Duc's analysis of the Beau Dieu of Amiens.69 Few have come close to the eloquence of Ruskin's description of the sculpture, the center of the portal, the center of the building, and the center of religion itself. A small indication of the impact of these thoughts is seen twenty years later upon opening Frederic W. Farrar's popular book The Life of Christ as Represented in Art. Its frontispiece is the Christ of Amiens and Farrar's description within the text repeats Ruskin's evaluation.70Norton knew Ruskin, Brooks knew Ruskin's writings, and certainly La Farge, of French heritage, knew Ruskin's ideas as well as Viollet-le-Duc and the sculpture itself.71 The success of the installation, it seems, came from the increasingly unusual context for modern times of a shared cultural expectations. La Farge did not replicate an image; he assimilated its form and power, and communicated it to an audience already receptive to the issues behind the selection of model.72

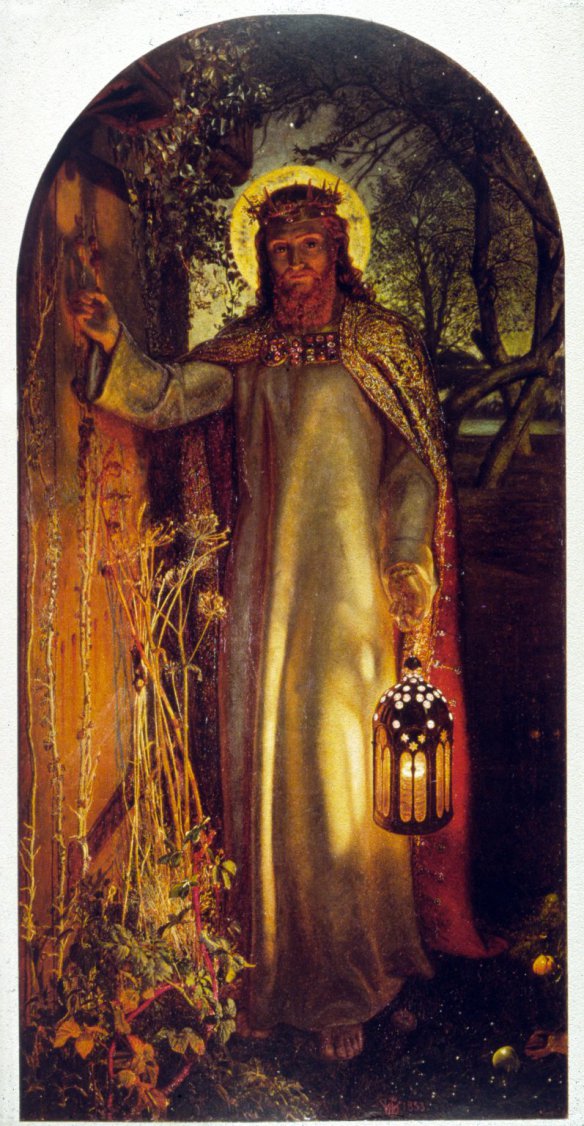

William Holman Hunt's The Light of the World

The ubiquitous replication of images from Pre-Raphaelite and German religious art, for the most

R. T. Giles and Co.,

Minneapolis, Minnesota, Light

of the World, 1905, after

William Holman Hunt, First

Presbyterian Church,

Salt Lake City, Utah.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin part, was less assimilated.73 What was essential was simply the visual correspondences between the known engraved or photographic replica and the image in glass. William Holman Hunt's painting The Light of the World,

William Holman

Hunt, Light of the

World, 1853, Keble

College Oxford.

Photo: londonby

gaslight.wordpress.comKeble College Oxford, shows Christ holding a lantern and knocking at a darkened door.74 The frontispiece in Henry Turner Bailey’s The Great Painters' Gospel, it became a perennial favorite in stained glass. One of the first examples may be a window placed on January 1876 in St. Luke's Church (now St. Luke and the Epiphany, Episcopal) Philadelphia. The subject was featured on the opening page of the 1876 catalogue of Cox & Sons, London, "By permission of Messers Pilgrim & Lefèuvre, publishers of the engraving of Holman Hunt's "Light of the World" Messrs Cox & Sons are enabled to supply this subject in stained glass."75 The site list in the catalogue further described the window as a "Large highly finished Stained Glass Renaissance W.(indow) after Holman Hunt's "Light of the World" with figure life size."76 The Gorham Company of New York advertised a Light of the World fabricated by Edward Peck Sperry in 1904.77 Sperry was a highly respected artist who had designed windows in the church of the Covenant, Boston, the Bernard and Godfrey window for Harvard University's Memorial Hall [See Appendix], and the Ivanhoe window at the University of Chicago.78 It was not poverty of talent that encouraged repetition of masterworks. St. James' Episcopal Church, Cambridge, Massachusetts, contains a turn-of-the century opalescent window that exploits the new glass to intensify the glow of the lantern.79 The Swedenborgian church also in Cambridge, Massachusetts, shows yet another manifestation of Christ and lantern.80 Such patterns could be duplicated by any large city at the turn of the century.

Civic and moral responsibilities

Often the American programs emphasized civic and moral responsibilities. The Church of the Covenant (Presbyterian),

Tiffany Studios, Cornelius and

the Angel (Thayer Memorial window)

Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims,

Brooklyn, New York.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin .jpg)

Tiffany Studios,

Cornelius and the Angel,

Church of the Covenant,

Boston. Photo: author in Boston's Back Bay, includes a window depicting the story of Cornelius the Roman Centurion, although a non-believer, justified in the sight of God because of his upright life. The popularity of the motifs is demonstrated by the same cartoon appearing in a window in Brooklyn’s Church of the Pilgrims. Images of Stephen distributing the wealth of the church or Mary and Martha ministering to Christ emphasized the role of charitable activities. The Good Samaritan was often depicted; a son returns to the family fold, a theme that reflected the same sociological issues so often a part of the moralizing works of artists like Greuze. The Old Testament, as well, was perused for models of civic responsibility and of familial relationship. Ruth's devotion to her mother-in-law Naomi (Ruth 1:11-18), as depicted in the nave windows of Vassar's collegiate chapel, was a valued theme.81

Priorities of all

Not only the Stanfords, but all patrons, collective or individual, wanted to see their own priorities reflected in the stories depicted in windows. Jane Stanford placed a church at the

Zettler Studio, Munich, Boy

Jesus in Temple, 1909, Cathedral of

the Madeleine, Roman Catholic,

Salt Lake City, Utah.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin heart of the campus, a move met with protest from some faculty, and endowed it with the most lavish decorative program of all the university buildings. Religion functioned as the primary means of expressing shared ethos as well a specific intent of Americans of this

R. T. Giles and Co.,

Minneapolis, Minnesota, Boy

Jesus in the Temple, 1905,

after Heinrich Hofmann, First

Presbyterian Church Salt

Lake City, Utah.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin era. A community's primary social activities, its celebration of births, marriages, and deaths, and the importance of family ties became highly prized images in glass. The Marriage at Cana, with all specific details of the moment was an invariable element of Marian and Christological cycles. Donors saw a strong connection between their own specific circumstances and the image. Agnes and Heinrich Hemmelgarn donated a Marriage at Cana window to the Roman Catholic Church of St. Paul, Cincinnati, to commemorate their golden wedding anniversary.82 Details of clothing, flowers, baskets of food, or the expressions of concern, love, or astonishment on the faces of the participants, were essential elements of the design. The window had been awarded a first prize at the World's Columbian Exposition

R. T. Giles and Co., Minneapolis,

Minnesota, Boy Jesus in the Temple,

detail, 1905, after Heinrich Hofmann,

First Presbyterian Church Salt Lake

City, Utah. Photo: Michel M. Raguin of 1893 and evidently was considered a major statement by the F. X. Zettler studio. The Festschrift for the studio published in 1910 reproduced the window in a large format and devoted two pages to critical reaction to the ten-meter tall Baroque design.83

Family life, especially the image of the child learning both intellectual and practical values as part of the family unit, dominated iconographic choices. Christ is invariably depicted blessing the Children, as in programs descibed in the appendices: St. James the Less, First Universalist Church, Trinity Church, Arlington Street Church, Stanford University, and Princeton University Chapel. Joseph was elevated in status from medieval supernumerary to model father and laborer, demonstrated in the Church of the College of the Immaculate Conception.

J & R Lamb Studio,

The Finding of Boy Jesus in

the Temple, (after Stanford

University cartoon)

1908-1910, First Presbyterian

Church, Orange Texas.

Photo: J & R Lamb Traditional images were modified to reflect these new priorities. For example, depictions of the Visitation in St. Michael's Catholic Church in Providence, Rhode Island, or in Blessed Sacrament Church, in Worcester, Massachusetts, added the husbands of both Elizabeth and Mary to the scene.84 They thus parallel the composition of the left wing of Rubens Deposition altarpiece in Antwerp discussed earlier. Joseph was seen instructing the boy Jesus in the carpenter's shop, often with Mary occupied by handwork. One of the most stunning

William Holman Hunt, The

Finding of the Saviour in the Temple,

1860. Birmingham Museum and Art

Gallery, Birmingham UK.

Photo: Pseudomoasexamples of the Holy Family at work is the sixty by thirty foot transept window showing Mary with distaff, Joseph cutting planks, and the child Jesus carrying wood that falls into the shape of a cross installed in 1893 in Sweetest Heart of Mary Roman Catholic Church in Detroit.85 Joseph also became a patron of a happy death, explaining the frequent images of the dying Joseph surrounded by Christ and Mary in American Catholic programs. The Holy Family itself, as Mother, Father and Child, became a new devotional icon. The child being led in its first steps, the growing son, still obedient to his parents' injunctions, and the grown man saying farewell to his mother, were the sociological phenomena behind representations of the Holy Family, the Finding of the Boy Jesus in the Temple or Christ Taking Leave of Mary before the Passion. These images articulated the moral and political role models of religious instruction in an age when churches strove against competitive new social movements. To study these sites is to see and experience the priorities of a diverse population before the great social changes of the 20th-century.

REFERENCES

![]()

1. ^ The City of Paris Dry Goods Company was one of the city’s most important department stores, operating from 1850 to 1976. Purchased by Neiman Marcus, it was demolished in 1981 to reopen with a new building designed by Philip Johnson, but incorporating the old rotunda and skylight. The loss of the building was deeply divisive, as it had been one of the rare survivors of the 1906 earthquake, and its rotunda and dome date to renovation of 1909.

2. ^ Collecting and imaging the past have been at the core of recent studies in the history of culture. Most notable are the books and articles by Francis Haskell: Rediscoveries in Art. Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion & Collecting in England and France (Ithaca, 1976); Past and Present in Art and Taste (New Haven, 1987), selected essays including "Manufacture of the Past in Nineteenth-Century Painting" (pp. 75-89) and "Old Masters in Nineteenth-Century Painting (pp. 90-115); and most recently History and Its Images (New Haven, 1993)

3. ^ These issues have received widespread attention through the translated work of Walter Benjamin, especially "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York, 1969), 219-53. See also Camille 1990 and Williams 1982, p. 124. See also Retaining the Original: Multiple Originals, Copies, and Reproductions. Studies in the History of Art, vol. 20 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1989), of which the collected essays of particular relevance for this study include those by Rosalind E. Kraus, Richard Shiff, and Alan Gowens.

4. ^ See Caviness 1992, pp. 103-104. It is significant that when large urban populations began to develop in late 12th-century Europe, cathedral, collegiate, or monastic churches were incapable of meeting the needs of the laity. The new mendicant and preaching orders, especially the Dominicans and Franciscans arose to minister to the new constituency.

5. ^ The Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden, trans. Denis Searby; intro. and notes Bridget Morris (Oxford, U.K; New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

6. ^ Sidney C. Hutchinson, The History of the Royal Academy (London, 1986 first ed. 1968). Sir Joshua Reynolds served from 1768 until his death in 1792 as the first president. See Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourses on Art, Robert R. Wark, ed. (San Marino, California, 1959), esp. Discourses IV, V, and VIII.

7. ^ Winston 1847, p. 189.

8. ^ Clara Erskin Clement, "Later Religious Painting in America," The New England Magazine 12/2 (April, 1895), 138. Clement wrote primarily on art, in 1878 publishing for Houghton, Osgood and Company the substantial A Handbook of Legendary and Mythological Art

9. ^ Rogier van der Weyden, about 1462, also called the Columbaaltar, Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Inv. Nr. WAF 1189-1191, from the church of St. Columba in Cologne.

10. ^ Boisserée sammlung. See also the prints at the British Museum online. Visits to the new collections such as Napoleon's plunder from Italy assembled in the Louvre in 1798, were often commemorated through prints. See Jane Vam Nimmen, "Friedrich Schlegel's Response to Raphael in Paris," in The Documented Image. Visions in Art History, Gabriel P. Weisberg and Laurina S. Dixon, eds. (Syracuse, 1987), 319-33, and Cadero-Gillette 1992, pp. 47-96.

11. ^ On the means of production and social control see Williams 1982, pp. 95-102.

12. ^ Düsseldorf Society for the Propagation of Good Religious Pictures [published by R. Washbourne, 18 Pater Noster Road] (London, 1873) comprises a large volume of lithographic reproductions. The reader can find both entire paintings and details such as the popular image of St. Cecilia abstracted from Raphael's St. Cecilia and Four Saints, Bologna.

13. ^ See collection of essays Das kunst- und kulturgeschichliche Museum in 19 Jahrhundert [Studien zur Kunst des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, vol. 39] eds. Bernward Deneke and Rainer Kahsnitz (Munich, 1977) and Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach, "The Universal Survey Museum," Art History 3/4 (1980), 448-469.

14. ^ By 1889 the Museum had only three curators, one designated for casts and reproductions. The following year a special committee was appointed to enlarge the museums cast collection. Calvin Tomkins, Merchants and Masterpieces. The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1970), 71, 79; Morrison H. Hecksher, “The Metropolitan Museum of Art: An Architectural History,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Summer 1995), fig. 23.

15. ^ The director was then Luigi Palma de Cesnola. Letter from (Mrs.) Wright of New York, Stanford University alumna, to Jane Stanford, October 13, 1895, Stanford University Archives.

16. ^ Charles Callahan Perkins, one of the original 12 trustees of the museum incorporated in 1870, had earlier stressed its educational aims: "Original works of art being out of reach on account of their rarity and excessive costliness, and satisfactory copies of paintings being nearly as rare and costly as originals, we are limited to the acquisition of reproductions of plaster...and photographs of drawings by the old masters, which are nearly as perfect as the originals from which they are taken, and quite as useful for our purposes." Whitehall 1970, vol. 1, pp. 8-9. Plaster casts occupied a significant portion of the original Copley Square building. A bitter controversy over their transferal to the new Huntington Avenue site, opened in 1909, forced Edward Robinson, Director, and advocate for reproductions, to resign. Whitehall 1970, vol. 1, pp. 44-6, 172-217. See also Martin Green, The Mount Vernon Street Warrens (New York, 1989), 134-36, 167-69. Kathryn McClintock, “The Earliest Public Collections and the Role of Reproductions (Boston)”in Medieval Art , 55-60.

17. ^ Dedication of Farnsworth Building of Fine Arts, October 23, 1889. The building was designed to provide areas for pictures and casts, study and books, studios, and a lecture hall. For general information on women's education see Helen L. Horowitz, Alma Mater: Design and Experience in Women's Colleges from their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930's (New York, 1993). I am grateful to Wilma R. Slaight, Archivist, Wellesley College, for reviewing information in this chapter.

18. ^ H. G. Wells, The Future in America (New York, 1906), 233. He wrote that to think of Boston itself was to think of reproductive images and plaster casts (p. 225) and felt that the "drawings of photographed Madonnas and Holy Families and Annunciations" prevented the young women from spending enough time on "living thought" of the world's present affairs (p. 234).

19. ^ Brimmer 1889.

20. ^ Brimmer 1889, pp. 9, 27. See also Idem, Address Delivered at Bowdoin College upon the Opening of the Walker Art School June VII MDCCCXCIV by Martin Brimmer (Boston, 1894), for many of the same concepts, especially pp. 26-27, for the role of photographs and plaster casts in the art museum.

21. ^ Brimmer 1889, p. 30. See also Whitehall 1970, vol. 1, p. 48.

22. ^ The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco were created in 1972 through the merger of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum and the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. See, among other museum publications, The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Selected Works (San Francisco, 1987), 7-18.

23. ^ Marius Amidst the Ruins of Carthage (Accession no. 49835) was painted in 1807 when Vanderlyn was in Rome. It was purchased by de Young at the Gumps Auction, San Francisco, 8 and 9 May, 1919, lot no. 10. See Marc Simpson and Jennifer Saville in The American Canvas, Paintings from the Collection of The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco (New York, 1989), 56.

24. ^ The museum soon outgrew its original building. Louis Christian Mulgardt designed a new building, under construction from 1919 through 1925, in a Spanish Plateresque-style to evoke the Hispanic origins of California. The exterior decoration consisted of multiple cast concrete elements over steel supports. This ornamentation gradually deteriorated in the moist, salt-laden air of the Golden Gate Park and in 1949 was replaced with a simple stucco facing.

25. ^ Extract of will in Registrar's files of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

26. ^ San Francisco Chronicle, April 15, 1933, p. 3. In 1927 Valentiner, Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts from 1925 to 1945, convinced Heil to leave a post in Florence to become chief curator. When the city cut off funds for curatorial salaries during the Depression, Heil left for San Francisco. Margaret Sterne, The Passionate Eye. The Life of William R. Valentiner (Detroit, 1980), 157.

27. ^ The full legal title of the university is The Leland Stanford Junior University. See Osborne 1986, for the most authoritative discussion of the founding of the museum. For an early eye witness report on Jane Stanford and the early years of the university, by its president, see David Star Jordan, "Jane Lathrop Stanford," Popular Science Monthly (August, 1909), 157-73. For the following analysis of the Stanfords, the museum, and the chapel, I am indebted to Carol Osborne. For invaluable assistance in researching the Stanford Archives, I am grateful to Laura Fan, San Francisco.

28. ^ After traveling Europe with his mother, the young man unfortunately contracted typhoid fever and died in Florence a few months short of his sixteenth birthday.

29. ^ The museum was conceived to improve the standards of design in British industry. In a pattern similar to the development of the H. M. de Young Museum, the London institution came into existence in the aftermath of the Great Exposition of 1851, and through the instigation of individuals who had been instrumental in the exhibition (the Prince Consort and Henry Cole, organizers of the Crystal Palace). See for fine illustrations of the early stages of the museum, John Physick, The Victoria and Albert Museum. The History of Its Building (Oxford, 1982). See Carol Osborne “The Grandest Museum in the World” The Origins of the Stanford Art Museum,” Sandstone and Tile 34/2 (Spring-Summer, 2010): 3-11 and Obsorne 1986.

30. ^ Brimmer 1889, p. 11

31. ^ Osborne 1986, p. 17.

32. ^ Osborne 1986, p. 52.

33. ^ Bush had studied with Jasper Cropsey and painted images of south America that paralleled such work painted by East coast artists such as Frederick Church. For recent studies on the implications of American taste, see David M. Lubin, Picturing a Nation: Art and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century America (New Haven, 1994), esp. landscape and genre painting, 54-105 and 159-204.

34. ^ See possible source in Henry Turner Bailey The Great Painters' Gospel, Pictures representing scenes and incidents in the life of Our Lord Jesus Christ with scriptural quotations, references and suggestions for comparative study (Boston: W. A. Wilde Company, 1900), Plate 27, Plockhorst, Flight into Egypt

See another version (simply scanned)

35. ^ Feb. 13, 1889, Letter to George Pendelton, Envoy of the United States, from Hohenthal, Secretary to the King of Saxony, giving permission for the replica, and recommending Karl Bertling, a painter in Dresden. The second Madonna is discussed in a bill of August 23, 1890 from L. Sturm, a painter and art dealer in Dresden, who speaks of "a second good copy of the Sixt. Madonna, that it may endure the severe criticism of artists." Stanford University Museum Archives. For copies of the material cited I am deeply grateful to Carol Osborne.

36. ^ Trinity Episcopal Church, Brooklyn, Connecticut. illustrated, The Hartford Courant, June 26, 1983, B4; Duncan 1980, p. 208.

37. ^ See Osborne 1986, p. 29, fig. 32, and pp. 37-44, for a discussion of other collections by San Francisco contemporaries of the Stanfords such as Judge Edwin Bryant Crocker and his wife Margaret Rhodes Crocker.

38. ^ Letter to Jane Stanford July 18, 1893, Stanford University Archives.

39. ^ Giovanni Masini, Firenze, "Collection de Tableaux originaux, modernes et copies," Copies of invoices in the Stanford University Museum Archives.

40. ^ Letter from Chauncy Murch, April 17, 1902, Stanford University Archives.

41. ^ George was the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the railroad and shipping magnate. The estate in Ashville, North Carolina was begun in 1889, supervised by the collaborative work of Fredrick Law Olmsted (landscape architect) and Richard Morris Hunt (architect).

42. ^ After the 1906 earthquake the museum was largely neglected and over time a large portion of its collections dispersed. The museum closed in 1945. In 1963, under the leadership of Prof. Lorenz Eitner, the new chair of the Art Department, it began a new period of growth. See Osborne 1986.

43. ^ Stockholm 1980. After a complex battle in the courts concerning the disposition of Leland Stanford's will, Jane Stanford was able to begin construction of the church in 1899. A good portion of the faculty, however, went on record suggesting that the center of the campus might be more fittingly used to house the University's library.

44. ^ Letter to S. Goodenough, Secretary, California Universalist Convention, March 15, 1896, Stanford University Archives.

45. ^ For a cursory historical note on the studio see Craig Kendall, "'102 Years Young', A Modicum of History from the J. & R. Lamb Studios," Stained Glass 54/2 (1959), 19-26.

46. ^ Jane Stanford's control of university funds was complete. A legal agreement of May 15, 1897, outlining the relationship between Jane Stanford and the University's President stated that she had "in her sole and exclusive possession and control all of the property, both real and personal, given and granted by her and her husband Leland Stanford, now deceased, to the Trustees of said University...." Stanford University Archives.

47. ^ Stockholm 1980, p. 34. Additional evidence of Jane Stanford's support of equal rights for women is found in her warm relationship with Susan B. Anthony, the major force behind the Women’s Suffrage Association, and explicitly in a letter to Prof. A. L. Eliot, at the University, January 28, 1900, stating "that the conception of the idea of having the sexes united and put on an equality in this institution was the result of my own suggestion to my husband. He was opposed to the idea at first, but after a day's consideration made this remark - that as I was a co-worker with him signing away as much property to the institution as himself, it was but right to consider my request which he did." Stanford University Archives.

48. ^ Letter to Maurizio Camerino, Venice, from Jane Stanford, March 20, 1902, Stanford University Archives.

49. ^ Alvar Gonzalez-Palacios and Steffi Röttgen, The Art of Mosaics. Selections from the Gilbert Collection [exh. cat., Los Angeles County Museum of Art] (Los Angeles, 1992), for example the mosaic after Titian's Girl with Fruit of 1830-34 [L84.38.3 MM109, p. 189, No. 88] or Caravaggio's Entombment of Christ of 1843 [L83.18.7 MM262, pp. 132-32, No. 41].

50. ^ Letter dated August 24, 1892, Stanford University Archives.

51. ^ Gath, "Three Hours with Stanford," The Enquirer, Oct. 25, 1887, also quoted in Stockholm 1980, p. 39.

52. ^ Cormack 2015, pp. 236-240. The chapel was given by Howard Heinz in memory of Henry J. Heinz, founder of the H. J. Heinz Company, and his mother Anna Margaretta Heinz. Howard Heinz, Henry’s son was personally responsible to reviewing bids and selected Charles J. Connick. See also Joan Gaul, Heinz Memorial Chapel (Pittsburgh, 1995).

53. ^ Harvard College, Class of 1871, First Class Report (Cambridge, 1872), 5-6. Of 157 students, 18 listed themselves as undecided, and one as a skeptic. The rest were associated with recognized sects, including 55 professed Unitarians and 32 Episcopalians. Thirty years later (Harvard College, Class of 1900, First Class Report (Cambridge, 1902), 16-7) the categories were listed in order; birthplace, occupation before Harvard, military service, and religious views. Of the 442 men in the graduating class only 66 did not give a religious affiliation, although there were three professed agnostics, and three atheists.

54. ^ It is significant that Phillips Brooks, then a member of the Board of Overseers, was instrumental in convincing the Governing Boards to lift constraint from worship. Morison [1936] 1964, pp. 366-67.

55. ^ The Werner Co.: 1899-1900. See also James J. Tissot, The Old Testament, parts 1 and 2 (New York: M. de Brunoff, 1904). Another version was published by C. N. Morang & Co., Toronto, 1899. See website by Felix Just, S.J., Gospel Illustrations by James Tissot with good images and links to other sources, including the the 2009 exhibition on Tissot at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

56. ^ The selection of the Lamb, Connick, or Tiffany studios in this study is intended only to serve as a reference for the generic situation that affected all studios at this time. The reliance of studios on printed images was standard. See the images predominantly after Hofmann and Plockhorst in the catalogue Suggestions in Religious Art from the Studio of Ford Bro. Glass Company, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Chicago (n.d). The survey of stained glass in churches in Rice County, Kansas, by the Sunshine EHE Unit, Coronado-Quivira Museum, led by Naomi Nelson, photographed by Clyde Ernst, in 1982 discovered a number of installations very similar to those described in the Ford Bros. catalogue. I am most grateful to Naomi Nielsen for making this information available to me. See also Weis 1991, demonstrating the wide use of 19th-century and Renaissance sources for opalescent, traditional European, and Second Gothic Revival styles.

57. ^ Many of the studios that provided windows in American buildings have closed and their libraries, materials, and records have been dispersed or lost. Fortunately the Connick studio records have been archived by the Boston Public Library, Fine Arts Department, a project supervised by the late Janice Chadbourne. A great number of Connick's books are listed in the chapter "Books from a Glassman's Library," Connick 1937, pp. 378-91, See also the records of the d'Ascenso studios in the Philadelphia Athenaeum, the Willet archives in the Corning Museum of Glass, and the Burnham archives in the Archives of American Art. I am particularly grateful to the late Helene Weis for her insights on the printed image sources available to studios.

58. ^ Olivier Merson, Les Vitraux (Paris, 1895); Westlake 1881-94; Maurice Drake, A History of English Glass-Painting with Some Remarks upon the Swiss Miniatures of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (London, 1912); Yves Delaporte and Etienne Houvet, Les Vitraux de la cathédrale de Chartres, 4 vols. (Chartres, 1926); Lucien Magne, Décor du verre (Paris, 1913); Hugh Arnold and Lawrence Saint, Stained Glass in England and France (London, 1913).

59. ^ Farrar 1900.

60. ^ 100th Anniversary Book 1889-1989 All Saints Church, Norristown, Pennsylvania (original quote from the Norristown Daily Herald 5/30/05). I am grateful to the Rev. Robert H. Coble for making this information available. [535 Haws Ave. Norristown PA 19401] The windows were designed by Samuel Mollyneux Jones and fabricated by the Alfred Godwin Studio of Philadelphia. Godwin was a native of Manchester, England. His style was influenced by the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, especially Burne-Jones.

61. ^ The window was removed from "Prospect" by Mrs. Harold W. Dodds in 1933, with the consent of the University, and stored in the University's chapel basement. Subsequently it appeared in a Pennsylvania antiques shop and was purchased by Merill Zinder who installed it in his restaurant, Charley's Other Brother, in Mount Holly, New Jersey (Town Topics, Princeton, New Jersey, April 8, 1981). I am grateful to James S. Graham of Princeton, New Jersey for bringing this window to my attention and to Mr. Zinder for his generous cooperation.

62. ^ This is one of the rare, if not singular, instances when Bing referred to a specific installation. Bing 1895, p. 132.

63. ^ Sketch for West Windows of Nave, Trinity Church, Boston 1883, Private collection, Henry La Farge in La Farge 1986, pp. 208-10, figs. 153-54.

64. ^ For overview of Brooks, see Joel Poudrier, "The Episcopal Church, Phillips Brooks, and Trinity Church: A Mural of Art with Sarah Wyman Whitman in its Center," in Raguin 1993; see also Allen 1901.

66. ^ For Eliot's influence see Kathryn McClintock, “The Classroom and the Courtyard: Medievalism in American Highbrow Culture,” in Medieval Art, 41-54; Martin Green, The Problem of Boston: Some Readings in Cultural History (New York, 1966), 122-41. Eliot was Ruskin's literary executor. See also Charles Eliot Norton, Letters of Charles Eliot Norton, 2 vols. (Boston and New York, 1913) and Brian Jorgensen in "The Education of Men: Harvard's Influence on the Development of Boston's Culture and Artistic Taste," in Raguin, 1993.

67. ^ Ruskin is probably best known today as the author of The Stones of Venice, 3 vols. (London, 1851-3) and The Seven Lamps of Architecture (London, 1849). For recent analysis of Ruskin's influence see Haskins 1993, 303-313.

68. ^ Ruskin [1880-84] 1904. Ruskin sent the first part of the book "By the River of Waters" to Norton in January 1880. See John Ruskin, Letters of John Ruskin to Charles Eliot Norton, vol. 2 (Boston, 1904, repr. 1905), 162. The book was projected as the first part of a long essay series "Our Fathers Have Told Us: Sketches of the History of Christendom for Boys and Girls Who Have Been Held at Its Fonts." The text was reprinted many times; for the Beau Dieu, see especially Chapter IV, sections 29-36. In 1903 translated into French with long introductory comments by Marcel Proust.

69. ^ Viollet-le-Duc 1869, vol. 3, pp. 216-18. The article is on the subject "Christ" where the sculpture at Amiens is illustrated in full and in a detail of the head. The author compares the head to Greek statuary, describing the High Gothic image as the supreme accomplishment of the type from the 11th through 16th centuries.

70. ^ (London and New York: The Macmillan Company, 1900), esp. 488: "Mr. Ruskin selects as the noblest ideal of Christ known to him a sculptured figure of the thirteenth century on the west front of Amiens Cathedral. ...Into this figure the artist has put a world of true and noble thought. Christ is standing at the central point of all History, and of all Revelation: the Christ, or Prophesied Messiah of all Past, the King and Redeemer of Future Time....."

71. ^ La Farge owned a number of Ruskin's works including Lectures on Art (Oxford, 1875), listed in Catalogue of a Portion of the Library of John La Farge [sale cat. #740, The Anderson Auction Company] (New York, March 24 and 25, 1909), Nos. 393-5. Client and patron intermingled intellectually and socially; Brooks, H. H. Richardson, and La Farge had viewed Giotto's Arena Chapel in Padua together. See John La Farge, The Gospel Story in Art (New York, 1913, repr. 1926), 279. Posthumous publication may explain why the cover came to be embossed with an image of Holman Hunt's Light of the World, discussed later in this chapter. A telling connection between Norton and Trinity was Martin Brimmer's long friendship with Norton. Among other joint activities, they had helped to found the Archaeological Institute of America in 1879, Norton serving as the first President and Brimmer as first Vice President.

72. ^ For discussion of these issues I am indebted to Jessica Butler, Visual Arts Major and Holy Cross graduate, class of 1993. See for a discussion of La Farge's complex sources and deliberate references to Palma Vecchio, Raphael, Giotto, Giovanni Pisano, and Cimabue, H. Barbara Weinberg, "La Farge's Eclectic Idealism in Three New York City Churches," Winterthur Portfolio 10 (1975), 199-228.

73. ^ For discussion of Rossetti's distrust of the then current wood engravings for reproduction, and his pioneering use of the photograph see Alicia Craig Faxon, "Rossetti's Reputation: A Study of the Dissemination of His Art through Photographs," Visual Resources 8/3 (1992), 219-46.

74. ^ Christopher Wood, The Pre-Raphaelites (New York, 1981), color ill. p. 43. The Light of the World was completed in 1853 and exhibited in the Royal Academy in 1854. This early version was sold to Thomas Combe of Oxford, whose wife later gave it to Keble College. Later Hunt painted the larger version in St. Paul's. See also William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2 vols. (New York and London, 1905), illustrated with engravings by the Swan Electric Engraving Company. The engraving of The Light of the World, opp. p. 368, vol. 1, demonstrates not only the image's importance, but the continued intervention of the mechanical reproductive process in the dissemination of influence. The image was the frontispiece for Henry Turner Bailey, The Great Painters' Gospel, Pictures Representing Scenes and Incidents in the Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ with Scriptural Quotations, References and Suggestions for Comparative Study (Boston: W. A. Wilde Company, 1900).

75. ^ Cox & Sons, London, Catalogue, 1876, p. 1. I am grateful to Jean Farnsworth for verifying the description and site of this window.

76. ^ Ibid. p. 6,

77. ^ Samuel Hough, "Notes from the Archives: Gorham's Stained Glass," Silver: The Magazine for Collectors (March-April, 1989), 18-21. Hough quotes extensively from the 1904 catalogue, The Gorham Company, Makers of Memorials, New York, mentioning Edward Peck Sperry as designer-in-chief of the Ecclesiastical Department. An image of Christ with the lantern, without the door is labeled "Dingee Memorial, signed E. P. Sperry '04" (p. 19). I am grateful to Gerald Farrell Jr. for bringing this article to my attention.

78. ^ Frank Dickinson Bartlett window, University of Chicago, Bartlett Memorial Gymnasium, 1904: Frueh 1983, pp. 106-9; Duncan 1982, color pl. 22. In 2001 the Gymnasium was converted to a Dining Hall and the window dismantled and put into storage.

79. ^ Commemoration "Rice Memorial window.

80. ^ Church of the New Jerusalem, 50 Quincy Street, Memorial to Seymour Howell, Harvard College class of 1892, who died in his junior year.

81. ^ See watercolor sketch, An Exhibition of the Work of John La Farge [exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art] (New York, 1936), No. 69.

82. ^ The inscription on a plaque painted at the bottom of the window: "Gestiftet von Heinrich und Agnes Hemmelgarn." After some years of inactivity the church was remodeled in 1981 to become St. Paul's Church Mart, a showroom for ecclesiastical products.

83. ^ The designer was identified as Prof. W. Lindenschmitt. Fischer 1910, pp. 94-95, pl. 65.

84. ^ Windows in St. Michael's date about 1912-1915, by Hardman & Co. Birmingham, England. I am grateful to Jennifer Lee Cadero-Gillette for help in researching this building. Windows in Blessed Sacrament church date about 1910, by Mayer & Co. I am grateful for the Worcester Ecumenical Council for their survey of a number of buildings in the city.

85. ^ Tutag 1987, pp. 112-13. The window was produced by the Detroit Stained Glass Works but appears to be based on French realistic scenic tendencies such as those of Merson or Champigneulle. Opalescent glass is used to advantage in the granite wall of the highly impressive "home in Nazareth" and the foliage in the background. The church was an ethnic Polish foundation.