This topic is so large that the writer begs the reader’s indulgence for being confined to a few broad outlines and several representative studios. The focus, as in most of this study, is on context. The taste for opalescent stained glass in the 1880s and 90s corresponded to a taste for greater opulence in both domestic and public spaces. Luxuriant colors and textures, achieved by the use of inlays and veneers of marble and wood, wallpaper, stenciled painting, and leaded windows all combined for an unusually rich effect often described under the rubric of the American Renaissance.1Homes across the country as well as public institutions such as libraries, hotels, courthouses, and banks invariably used decorative glass.

The public sphere

Unidentified

American studio,

Songbird, Eastlake

style home, 1886,

Pacific Heights, San

Francisco. Photo: author

Tiffany Studios, supervision, D.

Maitland Armstrong, Dining Hall,

detail, 1887, Ponce de Leon Hotel,

now Flagler College, St. Augustine,

Florida. Photo: authorGiven the popularity of the medium, competitive

James Baker & Sons,

Aesthetic-style window, 1877,

Barron Arts Center (formerly

Barron Library), Woodbridge,

New Jersey. Photo: authorinnovation was inevitable. In 1877, the Barron Library in New Jersey would install aesthetic-style panes produced by the English glazier, James Baker, who had set up a studio in New York. The delicate naturalistic foliage in paint and silver stain is relieved by accents of dense pot-metal colors.2 By 1887, the American-born creators of opalescent were the flagship studios. Tiffany windows were installed in St. Augustine’s premier luxury hotel, the Ponce de Leon in 1887. Paint was minimal; rather the inherent tone and hue as well as texture of the glass itself animate the design. Libraries were often one of the most significant statements of taste as well as conspicuous largess.

Richardson’s Libraries

The Thomas Crane Memorial Library in Quincy, Massachusetts was built in 1882 through the generosity of Thomas’

John La Farge, Old

Philosopher, 1883, Crane

Memorial Library, Quincy

Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinwidow Clarissa Starkely Crane and their two sons.3 H. H. Richardson, the premier architect

H. H. Richardson, Crane Memorial

Library, fireplace, 1882; John La Farge,

Resurrection, 1890, Quincy,

Massachusetts. Photo: authorof the time, was engaged to create a building that has continually been cited in surveys as one of the hundred most significant buildings of the United States.4 The window of the Old Philosopher by John La Farge was probably installed in 1883, and thus conceived as an integral part of the

H. H. Richardson, Crane Memorial

Library, reading areas, 1882, Quincy

Massachusetts. Photo: authorbuilding. In keeping with the experimental nature of glass at the time, it pioneers new techniques of fusing, its subject matter, typically, based on an Early Christian relief.5 The rich interior of the library, enveloping the reader with luscious wood textures and color stands as a model for many buildings of the time. These buildings, invariably supported by a wealthy donor, were part of the ethos of noblesse oblige that encouraged the public display of wealth and artistic taste though acts of philanthropy. In 1890 La Farge produced a memorial window for Benjamin Frankin Crane, one of Thomas and Clarissa’s sons, installed to the left of the great fireplace. A larger panel, its construction relies on a technique known as plating, layers of opalescent glass of different textures and hues that model space.

McCaw, Stevenson & Orr's "Glacier"

Window Decoration, Decorator and Furnisher,

7/4 (January, 1886): 130 Stained glass had become so "de rigueur" in domestic as well as public spaces that the market developed stained glass substitutes, a type of patterned transparent paper that was applied to windows, doors, and transoms. The Decorator and Furnisher, a popular journal for the building trades, regularly carried adds for a trade product called Glacier assuring the buyer that the material possessed "all the appearance of real stained glass, at a fraction of the cost."6 In the early years of the 20th century, Glacier was advertised as ecclesiastic product, shown with a figural image and accompanying text that proclaimed "We make a specialty of memorial windows."7 The S. H. Parrish & Co. of Chicago advertised what it called "stained glass paper . . . Many thousands of homes and churches have our glass paper in use. Why not you?"8

Domestic commissions from America's elite: Frederick Lothrop Ames

The town houses of America's elite were certainly not candidates for the stained

John La Farge,

fabricated by Thomas

Wright, Wisdom

Enthroned, detail of

Age, Oakes Ames

Memorial, 1901, Unity

Church, North Easton,

Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin glass substitute. Often extremely elaborate cut, molded, and painted glass was arranged in complex figural, floral or geometric designs. Such glass appears in Boston clustered in the great residences around Commonwealth Avenue. The houses exemplify the new residential type where great entrance ways and majestic staircases took the place of the old drawing rooms. Functioning as the preeminent grand interior face of the home around the turn of the century, such entrances were invariably designed to receive stained glass. The redesign of 306 Dartmouth Street for Frederick Lothrop Ames in 1882 included a lavish wood panel reception hall. Ames was the treasurer of the Ames Shovel Company in North Easton, an important manufacturing enterprise that allowed the family to play a prominent role cultural and intellectual life. The La Farge windows from the staircase landing showing Hollyhocks and Flowering Cherry Tree and Peony are now in the St. Louis Art Museum, Two windows from the west wall of the great hall on the ground floor of Peacocks and Peonies are now in the collection of the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The entire area was lit by a skylight with La Farge's glass over a mural cycle on the theme of the emperor and lawgiver Justinian by the French academic painter Benjamin Constant.9 The Ames family would later commission La Farge to produce memorials for Frederick Lothrop Ames’ sister Helen Angier Ames and nephew Oakes Angier Ames for the Church of the Unity North Adams.

Commonwealth Avenue home of William Powell Mason, Jr.

Rotch and Tilden, entrance hall of

the home of William Powell Mason, Jr.,

211 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston,

1883. Photo:priceypads.com In this era, the collection of old glass, the inspiration of new figural glass in an eclectic but predominantly Renaissance mode, such as that of La Farge, or the installation of richly patterned decorative work were interchangeable. Above all, the glass of the opalescent age took its place within the overall schema of the building. The home of William Powell Mason, Jr., at 211 Commonwealth Avenue, exemplifies the seemingly universal use of stained glass in a domestic interior.10 The Back Bay residence was designed in 1883 by the firm of Rotch and Tilden in a rich Queen Anne style. Rotch, a graduate of Harvard College and the architectural school of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, also collected ancient stained glass. The three late 15th-century panels from Milan Cathedral now in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology once decorated his Paris studio; they were donated to the Institute after his death by his sister Annie Rotch Lamb.11 Rotch's interest in medieval and Renaissance stained glass, as well as his design of buildings which received the new opalescent glass, is typical of his time. Stanford White (1853-1906), a partner in the firm of McKim, Mead, and White, architects of Boston's Public Library, both collected and commissioned stained glass for himself and his clients.12 The Payne Whitney House in New York City, the site of La Farge's 1902 panel of Autumn, was once also decorated with medieval glass that White had purchased on his European trips.13 McKim, White's partner, installed medieval and Renaissance glass in the lavish library of J. Pierpont Morgan constructed between 1902 and 1907 in a predominantly classical mode.14

In the Mason home, the great mahogany staircase is focused by a curving bay of predominantly white glass with

Ripple glass

window, entrance

stairwell of the home of

William Powell Mason,

Jr., Commonwealth

Ave. 1883. Photo: author borders and medallions of variegated opalescent hues.15 The white glass is a ripple design, but highly variegated so that no adjacent areas appear cut from the same section. The pattern of cuts is also intricate, demanding a meticulous attention to technique. Despite the high level of craftsmanship displayed by the commission, a display comparable to the intricate carving of the banisters and wood paneling, the ultimate impact of the glass is conditioned by its placement, both letting in considerable light and yet acting a screen between exterior and interior space. Although each panel is harmoniously designed and well executed, the significance of the commission depends on the ensemble. In 1895 a music room was added to the rear of the house, which incorporated a more classical design in the ionic columns and coffered moldings surrounding the windows, cream-colored walls, and classical fish-scale and lattice design for the pale stained glass.

Historic sites embellished with opalescent programs

Richard Mundy, Trinity Church,

building 1725, Tiffany Studios windows

1896-1910, Newport, Rhode Island.

Photo: Sketching a present.com Often these windows were part of a renovation or embellishment of an earlier structure installed to bring the building and its owner up with current trends. The additions to domestic structures paralleled the intrusion of opalescent windows into many earlier houses of worship. The practice was widespread, even in the most prestigious early-American structures, such as Trinity Episcopal Church in Newport, designed by Richard Mundy in 1725 after Old North Church in Boston, and ultimately Christopher Wren's Saint James in London. Opalescent windows by the Tiffany studios were added between 1896 and 1910.16 The Tiffany program introduced into the mid-19th century structure of Boston's Arlington Street Church will be discussed later.

Studios convert to opalescent

Roger Riordan, writing in 1881, noted that much of the American work could stand comparison to good European work, and "not a little" being far superior to Europe's best, when in the preceding decade "there were but eighteen makers [studios?] of stained glass in the United States."17 Riordan's observation, despite the problematic statistical accuracy, suggests the impact of an observable expansion in stained glass manufacture in the country as a whole. New workers, as exemplified by Armstrong, Tiffany, and La Farge, to be discussed later, entered the fast-growing industry. But many firms simply shifted their emphasis.

Riordan Studios of Cincinnati,

1890’s. Photo: courtesy

Riordan StudiosThe early American studios had been places where all types of work of glass cutting and decorative etching work was undertaken, in addition to leaded and sometimes "stained" windows. Much of their output was functional and established studios most frequently ran on the "bread and butter" commissions of etched patterns on carriage doors, entrance ways, and railway cars. The shift from the journeyman work of glassware to glass painting that occurred is exemplified by the oldest continually operating firm producing stained glass in the United States, the Riordan Studios of Cincinnati.18 (O12) The firm began in 1838 as Coulter & Finagin's Glass Cutting Establishment, advertising "cut and plain glass ware . . . window glass obscured and cut to any pattern desirable."19 Only in 1871 did the firm, then called William Coulter & Son, begin to advertise as “glass stainers.” The J & R Lamb Studios was founded in 1857 by brothers Joseph and Richard Lamb, immigrants from Lewisham, England.20 The firm accomplished many significant installations for churches, public institution and residences, echoing prevailing tastes, including gothic and aesthetic style. Lamb transitioned quickly into producing opalescent windows, as exemplified by its complete glazing of Stanford Memorial Church for Stanford University in 1898-1903, discussed in the essay on Museum and Church.

Continuation of other styles

Charles Brigham, Albert Cameron

Burrage home, 314 Commonwealth

Avenue, Boston, 1889.

Photo: backbayhouses.orgThe predominance of opalescent glass in windows did not mean that glass painting

Unidentified studio,

ships, Albert Cameron

Burrage home, 314

Commonwealth Avenue,

Boston, 1889.

Photo: authordisappeared. Often painted medallions were part of an unpainted opalescent glass framework. It was not unusual to find the white glass and enamel painting in almost the same technique used in the Renaissance. The three windows that grace the stair landing of the Albert Cameron Burrage home at 314 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, show none of the modern techniques yet resonate perfectly with the rich tones and intricate wood and marble carving of the interior. Burrage, a graduate of Harvard College and its Law School, was impressed by the Vanderbilt mansion in New York City and in 1899 commissioned Charles Brigham to build a similarly opulent residence in Boston.21 The Back Bay structure incorporates faithful quotes from the Loire valley châteaux, such as Chenonceaux. The windows are similarly historically correct. Typical Renaissance vertical and horizontal lead patterns carry across the realistic scene. The three Renaissance galleons flying the colors of France, England, and Spain, provide a fitting subject and mode for the Chateauesque architectural setting.

The American Renaissance: client and artist on the same social strata

The changed economic climate in the United States and the transformation of taste in the decorative and architectural arts were key to the development of the peculiar American product of the opalescent window. The tastemakers were the wealthy elite. The artists, not infrequently, came from the same social strata, and often considerable wealth, such as Tiffany. The two giants in the field, undoubtedly, were La Farge and Tiffany. Given the wealth of material published on both artists, the following remarks are in no way comprehensive, but simply hope to help localize their places within this dynamic era.

John La Farge: early formation

John La Farge and associates,

Trinity Church, Boston, interior,

1876-1879, chancel renovations by

Maginnis and Walsh, 1928.

Photo Michel M.RaguinOne might characterize La Farge as an artist who by choice and circumstance of patronage, elected to exercise his painting as an aspect of the decorative arts as well as at the easel. He was born March 31, 1835, in New York, the son of John Frederick La Farge and Louisa Binsse de Saint-Victor, French émigrés. His early education was bilingual and emphasized literature and art. His Roman Catholic background encouraged Roman Catholic schooling and he matriculated at Mount Saint Mary's College, Maryland receiving a Bachelor’s degree in 1853 and a Masters in 1855. Following this he studied law in New York while continuing to mingle in artistic circles. From April 1856 to the fall of 1857 La Farge traveled in Europe, predominantly France and Belgium, broadening his literary and artistic horizons by contact with his mother's cousin Paul de Saint-Victor, a well-known Parisian literary critic, and the study of the paintings of Delacroix and Chassériau, among others. He enrolled briefly in the studio of the academic painter Thomas Couture, as had William Morris Hunt in 1847, and associated with the painter/muralist Puvis de Chevannes, later responsible for the murals in the stairwell of the Boston Public Library

La Farge and the context of painting

John La Farge, Athens, 1898,

Walker Art Gallery rotunda , Bowdoin

College, Maine.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin During the following years La Farge established studio space in New York and continued to broaden his circle of artistic and cultural acquaintances, which included the architects of Harvard's Memorial Hall, William Ware and Henry Van Brunt, the philosopher William James, the novelist Henry James, and muralist William Morris Hunt, with whom he studied in Newport, Rhode Island. From 1860 through 1876 La Farge worked on paintings and illustrations. In 1874 Ware and Van Brunt, representing the Harvard class of 1844, offered him the commission for The Chevalier Bayard window for Harvard's Memorial Hall, a project never completed.22 From 1876 through 1877 he was engaged in stages of the mural decoration of Trinity Church, and from this time onwards he designed extensively in the applied arts of murals and monumental stained glass until his death in 1910.23 La Farge’s mural showing the allegorical representation of the city of Athens in the rotunda of the Walker Art Gallery, Bowdoin College, shows his deep Renaissance sources.24

The details of La Farge's initiation into making windows formed part of the previous discussion on his work in Boston at

Eugène Delacroix, Jacob Wrestling with

the Angel, 1861, church of St. Sulpice,

Paris. Photo: ignis Harvard and at Trinity Church. It is clear from the beginning that La Farge approached stained glass from a painter's viewpoint. He was interested in the possibilities of developing in the medium the modulation of color in hue, value, and intensity familiar to him from the experience of oils on canvas. His European ties reinforced this. He began his experiments with glass at the very time that France was undergoing an intense reevaluation of the nature of color and light, scientifically through the studies of the Parisian physicists such as Eugène Chevreul and experientially through the art of Delacroix and the widely admired murals such as ceiling of the Galerie d'Apollon in the Louvre of 1850 or the murals in the church St. Sulpice. La Farge probably read Chevreul's work on optics as early as 1855. His early exposure to the aspirations of William Morris Hunt for poetic figural painting built on European models further marked La Farge's development. He was an unusual figure, an artist as much at home in a literary and academic world as he was in the studio.25 His espousal of mural painting affected his conception of the stained glass window; he pursued the same issues of monumentality and dramatic power in both.26

Enthusiastic reception

Although painted and leaded glass had been the traditional method of the stained glass window as Europe knew it, the American development of variegated colors and surfaces within the material itself precipitated a new critique of paint on glass.27 It soon became immensely popular,

Nicholas Clayton, architect,

stairwell, Gresham House, 1887-1892,

Galveston Texas. Photo: Galveston

Historical Foundation Website especially as it mingled well with the variety of forms and textures of the eclectic styles of the time.28 Supporters of opalescent design were enthusiastic, if perhaps somewhat exclusionary in their commitment, as evident in Riordan's analysis of a "Window in Pure Mosaic" by John La Farge. "In this sort of work the style should always be pure mosaic. There need be no lack of variety. Besides the endless combinations of geometrical forms, derivable from mediaeval designs, the Arabesque and Japanesque systems of abstract ornamentation are in practice drawn upon by all our designers. Mr. La Farge has led off with Renaissance designs in pure mosaic . . . The simple shapes of the lower animals and plants are easily imitated in this manner. Their forms may be indicated by the leading alone, or may be rendered with an almost illusive naturalness by the choice of wrinkled, bulging, and concave pieces of glass, as is done by Mr. Tiffany . . . Even in the case of the largest and most important work, the benefits conferred by enamel are, for the most part, obtainable also in mosaic. The partial opacity which it gives, at some artistic cost, can be got in the glass itself without any loss of surface quality. The legitimate use of enamel is thus reduced to the gaining of additional form by vigorous drawing in dark hatchings over the colored and self-shaded pot metal."29

Such opalescent glass with shading aided by vitreous paint appears in La Farge's Harvard Battle window, installed a year after Riordan's article.30 It was not the presence or absence of surface paint that distinguished the opalescent window from the traditional European product, although simplistic definitions like this have been applied retrospectively. The new window partook of a new aesthetic emphasizing abstract design principles as well as monumental pictorial imagery. The American opalescent window was born as part of a total reassessment of the decorative arts.

La Farge: a personalized expression

The work connected to La Farge has a personal stamp, similar to that of Christopher Whall whose windows are discussed in the chapter on the Arts and Crafts movement. He was not the head of a studio, as was Tiffany, but a single designer working with a team of highly trained assistants and craftspersons who had come to understand the technical processes necessitated by his particular artistic vision. It is inappropriate, then, to compare La Farge's production with that of firms such as Mayer of Munich, Clayton & Bell of London, or even Tiffany, who responded to a much broader-based market. La Farge's known production of figural windows numbers in the hundreds, compared to the close to ten thousand commissions recorded for some of the large commercial studios.

It is significant that La Farge was a designer for the "deep pocket client," and when one addresses the context of a public art this issue is crucial. The materials and labor intensive procedures employed by La Farge simply priced him beyond all but the most elite patron. His first major figural commission in glass (The Chevalier Bayard window) was lost to Powell & Sons of London, not because of a failure of his art, but simply because his projected cost for the window for Harvard's class of 1844 amounted to twice as much as the class had allotted.31 Nonetheless, both La Farge and Tiffany were the front-runners of a stylistic revolution that was to dominate the progress of American stained glass for almost four decades. All other studios measured themselves against these standards. Critics, art historians, and even collectors are now beginning to reevaluate both the artists of this period and their historical context.

Louis Comfort Tiffany: a collaborative enterprise

Frederick Wilson,

designer, Tiffany Studios,

fabrication, Madonna, Church

of the Covenant, Boston,

c. 1900, after Pascal Adolph

Jean Dagnan-Bouveret,

Madonna of the Trellis 1888.

Photo: author

Tiffany Studios, Christ Leaving

the Praetorium, 1888, St. Paul's

Episcopal Church, Milwaukee,

Wisconsin. Photo: JonathunderOne of the major differences between the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany and La Farge was Tiffany's attitude toward collaborative design. Unlike La Farge, who conceived of his works as personal products, Tiffany was quite willing to cooperate with designers of repute, and even those of lesser stature. He also frankly acknowledged his adaptation of well-known paintings as the basis for stained glass designs, for example his Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit after Botticelli.32 The works were reused as the demand grew, for example

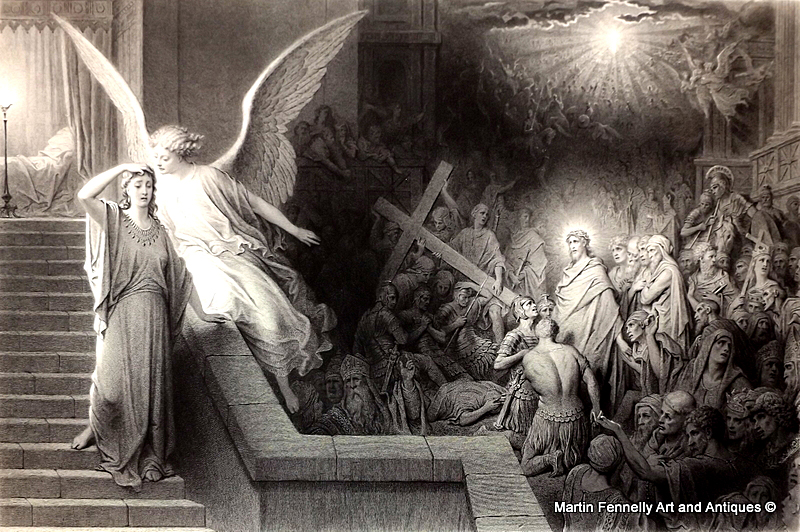

J & R Lamb Studio, The

Dream of Pilate’s Wife (after

Gustave Doré) 1908-1910,

First Presbyterian Church,

Orange Texas.

Photo: J & R Lamb the Madonna and Child window in the Church of the Covenant, Boston, after the painting by Dagnan-Bouveret, reappears in theBradbury Memorial in the First Congregational Church, Augusta, Maine.33 Works of Gustave Doré often served as a base, such as Christ Leaving the Praetorium, in a large window made in 1888 for St. Paul's Episcopal Church, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the central panel later repeated for St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Washington DC.34 It is important to note that other studios in these era were using the same sources, as addressed in the essay:

Gustave Doré, The Dream of

Pilate’s Wife, engraving, 1877.

Photo: Mark Fennelly Arts and Antiques

“Patronage: The Taste of the Time Reflected in Glass, or the American Museum and the American Church.” The J & R Lamb Company produced glass on the same level as Tiffany Studios. As did Tiffany, the studio worked with reproductive print sources, transforming them into a color drenched, palpable, architectural experience. A comparison between a print after Gustave Dore’s Dream of Pilate’s Wife and the Lamb Studio’s window reveals the restructuring of composition from horizontal to vertical format and the poignant focus on the dialogue between the woman and the angel.35

In 1884 Tiffany entered into an agreement with Siegfried Bing, the Parisian art dealer, to fabricate windows after designs by French artists, including Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Félix Vallotton, which Bing exhibited at his gallery, the "Salon de l'Art Nouveau" in 1885.36 Three windows for Harvard's Memorial Hall were fabricated by the studio after designs by Francis David Millet in 1889 [See Appendix].37 The studio also produced a window honoring Minne-ha-ha after designs by Anne Weston from Duluth; it was displayed in the Minnesota Building at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago of 1893.38 Such an approach may be the result of his origins exposing him as much to the tradition of American business as to art.

Tiffany’s formation

Tiffany Studios,

paperweight glass vase,

c. 1902, engraved Louis C.

Tiffany R2367. Photo:

Heritage Auction online Tiffany was born in 1848, the son of Charles Louis Tiffany, founder of the jewelry company,

Maitland Armstrong designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication,

c. 1885-1886, St. Columba,

Middletown, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Tiffany & Company of New York.39 His early life was one of wealth, comfort, and exposure to the importance of sound business practices. Despite a rather desultory education, military school as a boy and then travel in Europe at the age of seventeen, Tiffany appears to have received all that was needed for critical success. His own career reflected a mingling of his love of the well-wrought object and an enterprising attitude about building customer demand and then serving the market. He aggressively marketed himself as an interior designer and supported the manufacture of objects that would allow for a total environment charged with his design. Throughout his life he remained highly sensitive to contemporary development in blown and molded glass in Europe.40 His leadership constituted a major step toward the turn-of-the century integration of the aesthetic of the American glass vessel and that of the window.

The Associated Artists

Tiffany's first association was with three other designers in 1879, Samuel Colman, Lockwood de Forest, and Candace Wheeler in the firm of Associated Artists.41Harper's Magazine characterized the association as dedicated to bringing "a new era in house decoration, where each member of the advisory firm should be a specialist of skill and ripe culture."42 Between 1881 and1882 the firm designed the interior of Mark Twain's sumptuous residence in Hartford , Connecticut and the Fifth Avenue mansions of Ogden Goelet and Cornelius Vanderbuilt II in New York. Newspaper accounts that describe Japanese, Chinese, Moorish, Classic, and East Indian elements reflect the eclectic

Tiffany Studios,

opalescent glass window,

1885, Seventh Regiment

Armory, 643 Park Avenue,

New York City. Photo: HABS

No. NY-6295-44,nature of the furnishings. By late December 1882, Associated Artists had redecorated the White House for President Chester A. Arthur. The decoration s of many rooms in the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York brought additional acclaim, especially the ground-breaking use of abstract design in pure opalescent glass. The embroideries by Associated Artists displayed in December 1883 in the Loan Collections exhibition held in aid of the Pedestal Fund for the Statue of Liberty, were called the "most decided advance in needle-work known to the century."43 The needle work section became dominated by women, and it may have been this gender issue that encouraged the dissociation of Associated Artists as an independent entity.44

An analysis of the praise of the needle work of the Associated Artists reveals the prevailing idea of the lesser position of the crafts and the higher position of painting that motivated both Tiffany and La Farge to emphasize the "painterly" elements of these new windows.45 Constance Cary Harrison's critique in Harper's Magazine described efforts to "produce an embroidered surface which would possess all the softness of painting in water colors, yet have the enduring quality of ancient hand wrought tapestries."46 The complex tulip appliquéd panel by Wheeler made about 1883–87, now in the Metropolitan Museum, gives an indication of the sophistication of the enterprise. The aim of these experiments was to create embroidered pieces that aspired to the level of art; this meant appropriating the qualities of easel painting. Harrison's reference to the "softness" of watercolor suggests a tonal variation within the color indicative of the manipulation of light into shadow. This hoped-for transformation of embroidery functions as a paradigm for all of the crafts: "a suggestion of light or shadow here and there, a deepening of tone in the hollow of plait or fold, a loving touch of the brush, as it were, supplying the gradations of tint that transform a lifeless surface . . . into a spirited portrayal, as by pigments, of some form of natural beauty."47 Harrison saw the embroidered tapestry brushed with life-giving color, the "gradations of tint" transforming "a lifeless surface" of needle work into a spirited portrayal" just as a dull monotonous city apartment could be transformed via color from wall to window as the space was flooded with tinted light48. All of the arts of this time, and especially, the opalescent glass window strove for this interpenetration of form and medium, elevating the crafts to a total experience that could be termed art.

The many products of the Tiffany enterprise

Maitland Armstrong designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication,

c. 1885-1886, St. Columba,

Middletown, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Tiffany's supervision of a life-long production of an astonishing assortment of vases, leaded lamps, jewelry, tableware, mosaics, rugs, chandeliers, wall coverings, and architectural elements, such as the columns from Laurelton Hall now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, may be traced to his initial move into artistic production as a decorator.49 In 1885 Tiffany's work in stained glass had progressed so that he formed a new company, the Tiffany Glass Company Inc., which in 1892 became the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, and in 1893 the glassware division incorporated as the Stourbridge Glass Co. and the Allied Arts Co.50 In 1898, a popular writer on the arts of the period, Cecilia Waern, wrote on Tiffany's Favrile glass for The International Studio.51

She described in enthusiastic terms the Corona glassworks with its stock of 200

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication,

Beatitudes: Blessed are the

Peacemakers, detail drapery glass,

1904, Arlington Street Church,

Boston. Photo: author to 300 tons of glass on hand in cases and numbered racks defining the selection of 5,000 colors. The machine rolled varieties appeared remarkable for their varieties of color. "A pane of dark blue and white, harsh and crude in reflected light, becomes suddenly glorious when seen in transmitted light, like a sunset all at once illuminating the sky in this land of rich effects . . . Other pieces suggest priceless onyx or lovely marbles, when seen in reflected light, shot through with throbbing color when held up to the window." Waern also described the hand-made glass that retained varying thickness, bubbles, and imperfections from the accidents of the throwing. "As many as seven different colours out of different ladles or spoons have been thrown together in this way . . . The throwing of certain masses and colour can be regulated, of course, and a definite design is often employed with a view to providing the glazier with 'useful' glass for obtaining certain effects of drapery, modeling or backgrounds . . . The famous Tiffany glass is made by manipulating the sheet while still hot, as one would do with pastry (with iron hooks, the hands cased in asbestos gloves) and pushing it together until it falls into folds."52

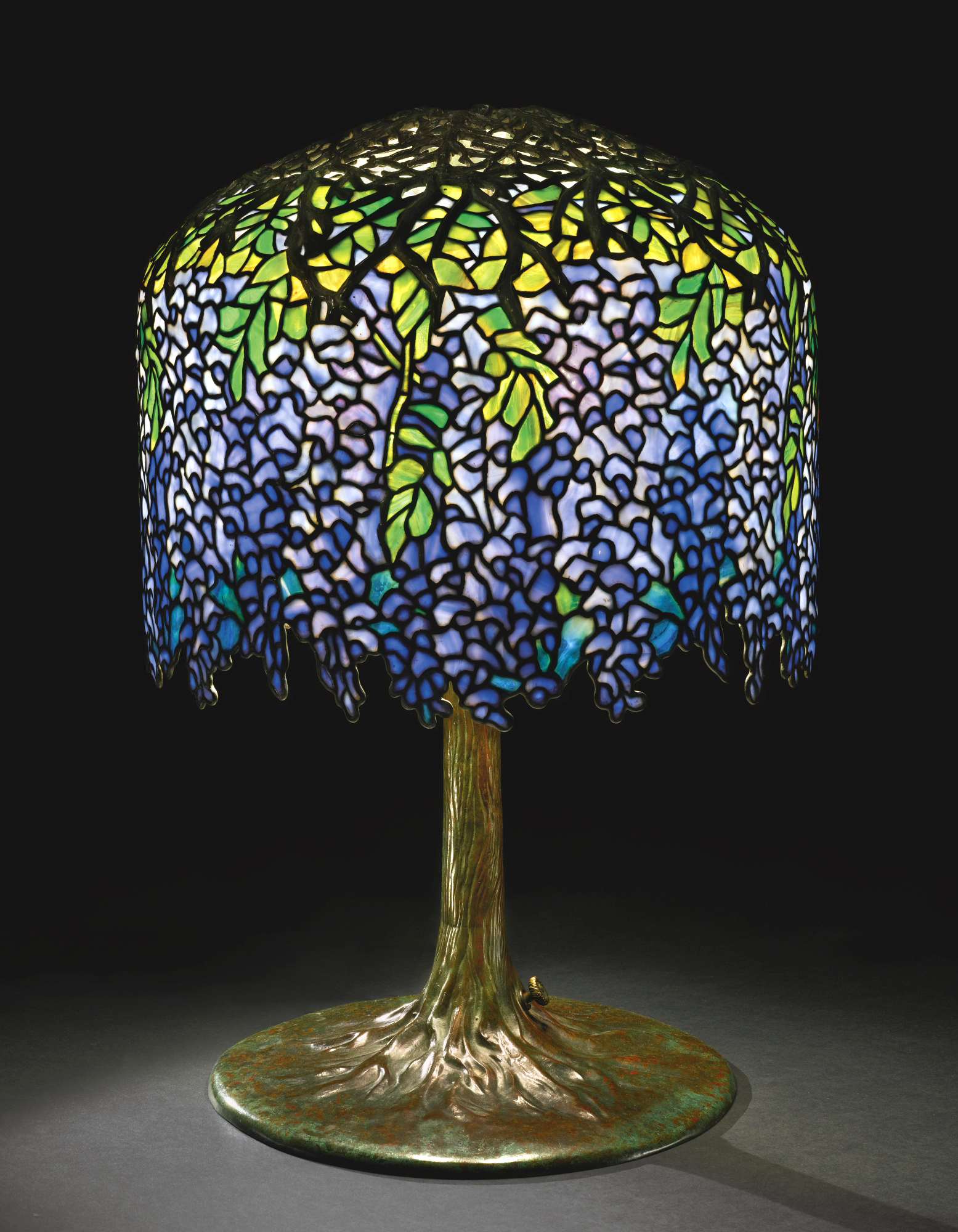

Tiffany Studios, Wisteria

Table Lamp, 1905, shade with

tag impressed TIFFANY

STUDIOS/NEW YORK;

underside of bronze armature

on shade impressed 10116.

Photo: Sotheby’s

Auctions onlineAlthough Waern spoke about the sheet glass in stock in the Corona Studio, seven of the

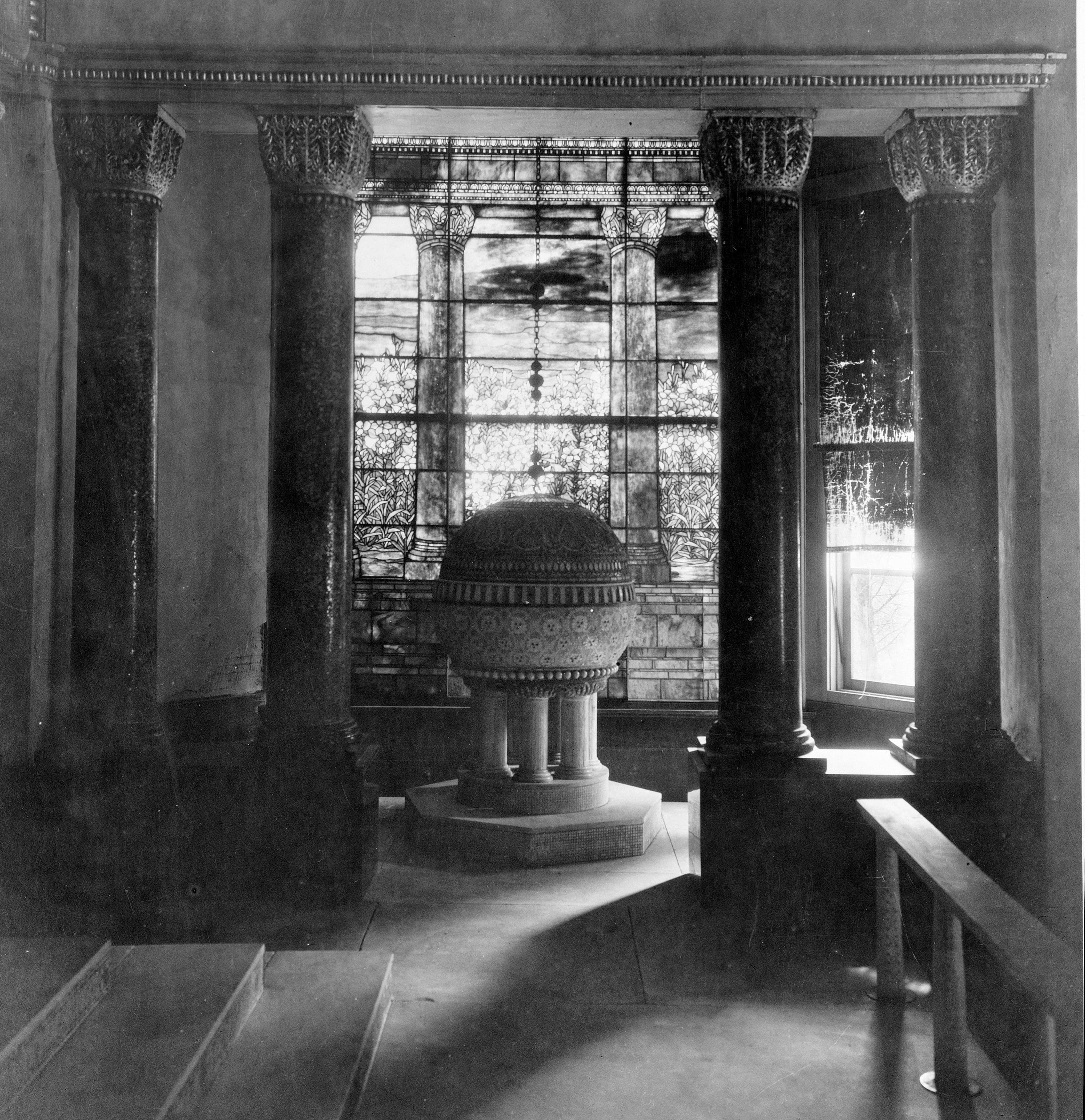

Chapel from the World

Columbian Exposition, Laurelton

Hall, Oyster Bay, Nassau County,

NY. Photo: HABS eight illustrations for the article are of vases, consistently labeled "designed and executed by Louis C. Tiffany," a misattribution that should no longer be tolerated. 53 The one window illustrated is the Deep Sea window. Waern wrote of mosaic work being accomplished by "young women working under Mr. Tiffany's directions." Women also appear to have supplied much of the labor in the production of the leaded lamps later to emanate from the Tiffany Studios.54 These women, undoubtedly, were responsible for the extensive mosaic work in the chapel made for the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893.55

The Tiffany Chapel and the World Columbian Exposition, Chicago

The theme of the Exposition was neoclassical and leaded and painted windows were not included.56 Tiffany prevailed upon his father to use some of the space that had been reserved for the Tiffany Jewelry Company in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. He installed the chapel, very much in an Early Christian/ Byzantine mode, and also exhibited stained glass of highly eclectic sources. The

Photograph of Madonna and

Child with Candle-bearing Angels,

1485-1490 by Sandro Botticelli,

Bode Museum, Berlin, lost to fire in

1945. Photo by Elisheva Marcus,

with permission from Bode Museum Entombment was modeled after 19th-century religious scenes such as those by the French Romantic painter, Eugène Delacroix and his Madonna and Child Window reproduced a painting by Botticelli, Madonna and Child with Candle-bearing Angels of 1485-1490, formerly in the Bode Museum, Berlin, and sadly destroyed while in storage during World War II.57 The panel Feeding the Flamingos was a more contemporary creation after Tiffany's own design. In the collection were several medallion windows that fused three-dimensional glass jewels inspired by Carolingian book covers with 13th-century stained glass designs.58 The exhibition impressed Siegfried Bing who was to play a pivotal role in the introduction of the new American glass to Europe.59

The Tiffany Studios at the turn of the century

.jpg)

Front facade of

Laurelton Hall,

Oyster Bay, Nassau County, NY.

Photo: HABS (3707667352) r

David Aronow, Photographer 1924In 1900 the firm changed its name to the Tiffany Studios, and in 1902 the name Tiffany Studios was extended to the glassware made at the Corona factory. From 1902 to 1905, at the height of his success, Tiffany built Laurelton Hall, a palatial residence on 580 acres of picturesque country in Oyster Bay, Long Island (New York).60 The residence, now destroyed, was resplendent with mosaics, stained glass, tile work, wall .jpg)

Living room of Laurelton Hall,

Oyster Bay, Nassau County, NY. Photo:

HABS (3707644026) David Aronow,

photographer, c. 1924 coverings, hanging lamps, and gardens almost as elaborate as the house itself.

Ayer Mansion, interior hall,

1899-1902, 395 Commonwealth Ave.

Boston. Photo: Yoon S. Byun, The

Boston Globe, 2013 Tiffany’s contemporary design for a residence on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue known as the Ayer Mansion reminds us of this glory. O31C The exterior was decorated in mosaics, the entrance hall a marble-lined place with curving staircase landing framed by a mosaic of colonnades. Stained glass windows in abstract patterns enhance ceilings and windows. The importance of opalescent glass, however, had begun to wane, as taste for the simpler forms of Moderne and Art Deco began their ascendancy. The Second Gothic Revival challenged the appropriateness of the "picture window" for a religious edifice, and Tiffany Studios began a gradual decline. In 1932, three year after the stock market crash of 1929, Tiffany Studios filed for bankruptcy and the following year Tiffany died at the age of eighty-four.61

1. ^ Examples of domestic glass windows of all levels of sophistication are gathered by H. Weber Wilson, Great Glass in American Architecture: Decorative Windows before 1920 (New York, 1986). For an overview of wealth and conspicuous display see Dianne H. Pilgrim, Richard N. Murray, and Richard Guy Wilson, The American Renaissance 1876-1917 [exh. cat. The Brooklyn Museum] (New York, 1979) and Wayne Craven. Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society (New York: Norton, 2009).

2. ^ James Baker moved to New York from London in 1867. The firm Baker & Sons remained in the city until 1888. Baker’s descendants continue to work in glass, notably out of El Paso, Texas. Melanie Kline Wayne, Whose House Are We (Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press, 2014), p. 113-15.

3. ^ Paula D. Watson. “Carnegie Ladies, Lady Carnegies: Women and the Building of Libraries,” (Libraries & Culture, vol. 31, No. 1 Readings & Libraries (Winter, 1996): 176. Richardson had already designed the Wynn Memorial library of Woburn, 1876-79 and the Ames Free Library in North Easton, 1877. His Converse Memorial Library, Malden, would follow in 1885.

4. ^ In 2007, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and Harris Interactive conducted a public poll.; the Crane Library was listed as number 43.

5. ^ Weinberg 1977, 372-88, figs. 275-77. The model was the 5th-century ivory diptych, the Muse Calliope and a Seated Philosopher, Monza cathedral Treasury, Monza, Italy.

6. ^ As early as 1875, Henry T. Williams and Mrs. C. S. Jones could devote a section of Household Elegancies: Suggestions in Household Art and Tasteful Home Decorations (New York, 1875) to imitation stained glass paper for the foyer. See "A Cheap Substitute for Stained Glass," the Art Amateur 1 (1879): 17; McCaw, Stevenson & Orr's "Glacier" Window Decoration, Decorator and Furnisher, 7/4 (January, 1886): 130, or W. C. Young's Stained Glass Substitute, ibid., 132. Substitutes for stained glass appear to have been a permanent option. See Bishop Hopkins' 1836 suggestions, above, The Anglo-American designer, part 1. Christopher Dresser, the important promulgator of Aesthetic Design discussed in The Anglo-American designer, part 2, wrote of substitutes in Principles of Decorative Design (London, 1873), 158-59: "glass, by the application of colour rendered transparent by varnish, can never be brought to resemble glass stained or painted by the legitimate method, either in delicacy of tint, or depth, or richness, and brilliancy of color. ....The designs which are printed on paper, with the view of imitating glass patterns err principally in being too elaborate, and in representing figures and scenery which are not in character or keeping with the designs that are usually represented in painted glass. If confined to simple diaper work, or borderings and heraldic emblems, as shown......the artistic effect would be more satisfactory although it can never equal genuine stained glass in depth of colour or purity of tone."

7. ^ Official Catholic Directory for 1911, 23.

8. ^ Official Catholic Directory for 1911, 38.

9. ^ John Sturgis, the architect of the renovations, designed the building so that guests would enter through a side door and be taken up by elevator to depose their wraps in second floor cloak rooms. The guests could then descend the grand staircase into the reception hall on the first floor. Bunting 1967, pp. 260-65, figs. 170-72. For the windows see La Farge, pp. 203-206, 254, figs. 148-49. Other panels are also extant in several locations. I am grateful to James Yarnall for assistance with this issue. See below, in the section on Memorials, for discussion of the Ames family memorials in North Easton, Massachusetts. See also James L. Yarnall, “Souvenirs of Splendor: John La Farge and the Patronage of Cornelius Vanderbilt II,” The American Art Journal 26/1&2 (1994): 66-105 for discussion of another installation of sculpture, embroidery, furniture, wall coverings, and stained glass, including skylights and transom lights of eclectic inspiration.

10. ^ Mason, whose father was a prominent Boston lawyer, also practiced law. He rose to millionaire status through management of estates and corporations, which included service as a director of the Old Colony Trust Company, the Merchants' National Bank of Boston, Boston and Lowell Railroad Company, Suffolk Savings Bank, and the Boston Pier or Long Wharf Company, among others. The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol. 26 (New York, 1943, reprint 1967), 181.

11. ^ The panels are figural, showing the life of St. Eligius and are hung in the Rotch library windows. Corpus Vitrearum Checklist I, pp. 58-59. See similar panels from Milan Cathedral dating to the 1480s now in Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

12. ^ I am indebted to Madeline Caviness for her research in this area. Two sales of White's collection were held in New York: The Artistic Property Belonging to the Estate of the Late Stanford White to Be Sold at Unrestricted Public Sale on the Premises No. 121 East Twenty-first Street [sale cat., American Art Association, 4-6 April] (New York, 1907); Illustrated Catalogue of Valuable Artistic Property, Collected by the Late Stanford White [sale cat. American Art Association, 25-27 Nov.] (New York, 1907). See overview of the highlights of the collection in Corpus Vitrearum Checklist III, p. 14.

13. ^ Now the French Cultural Embassy. Weinberg 1977, pp. 417-19. For additional insights into White's eclectic manner see the analysis of Harbor Hill, Roslyn, Long Island (New York) by Lawrence Wodehouse, "Stanford White and the Mackays: A Case Study in Architect - Client Relationships," Winterthur Portfolio 11 (1976): 213-33, and Wayne Craven, Stanford White: Decorator in Opulence and Dealer in Antiquities (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

14. ^ Now open to the public as the J. P. Morgan Library. See Corpus Vitrearum Checklist I, pp. 180-86.

15. ^ Bunting 1967, pp. 264-71, figs. 173-81. The studio responsible for the glazing of the Mason home still remains to be identified. For Arthur Rotch, see Harry L. Katz, A Continental Eye. The Art and Architecture of Arthur Rotch [exh. cat., The Boston Athenaeum] (Boston, 1985).

16. ^ See Duncan 1980, p. 222.

17. ^ Riordan 1881, p. 229.

18. ^ Now merged with the BeauVerre Studios in Middletown, Ohio. Virginia Raguin, "John A. Riordan, SGAA Life Member," Stained Glass 81/1 (1986): 21-24.

19. ^ Charles Cist, Cincinnati in 1841: Its Early Annals and Future Prospects (Cincinnati, 1841), 57. The tables of manufacturing and industrial products listings include only one glass cutter employing five people.

20. ^ See Barea Lamb Seeley, Ella’s Certain Window: Ella Condie Lamb (King of Prussia Pennsylvania: Centennial Printing, 1998), esp. 131-138.

21. ^ Bunting 1967, pp. 303-307, figs. 198-99. In 2002 the building was converted into four apartments but the entry vestibule with its windows and several other common areas designated as landmarks to insure their preservation.

22. ^ Weinberg 1977, pp. 339-43; Julie Sloan and James Yarnell, “Art of an Opaline Mind” The Stained Glass of John La Farge,” American Art Journal nos. 1-2 (1994):5-7, fig. 2; Raguin 2008, p. 193-94.

23. ^ For an overview of his work see Weinberg 1977, Yarnell 2012, and the collected essays in La Farge and Howe 2015. La Farge's working methods deserve some comment. In October 1882 La Farge formed The La Farge Decorative Art Company, associating with, among others, Mary E. Tillinghast who headed the tapestry division of the enterprise. In January 1885, the company was dissolved due to a dispute over the execution of the Angel of Help window for Unity Church, North Easton (see the essay on Memorials). La Farge had attempted to transfer the commission to another fabricator and La Farge's partners took legal action against him, resulting in the artist's arrest. John Calvin and Thomas Wright, former glaziers of the company, incorporated on their own as the as Decorative Stained Glass Company, New York, and continued to execute works after La Farge's designs. It is essential to correct a recent misattribution that has come into print. La Farge was in no way a collaborator with Rosenkranz of the window in Wickhambreaux, England, as cited by Morris 1988, pp. 76-77. The Decorative Stained Glass Company fabricated stained glass windows for a number of clients, such as La Farge, Crowninshield, Tillinghast, J. & R. Lamb, and Rosenkranz, but the designers were not working together. I am grateful to James Yarnall for giving a definitive explanation for this puzzling attribution.

24. ^ Weinberg in La Farge, p. 187, fig. 140. See the rotunda’s companion murals representing Rome, Venice, and Florence by equally renowned mural painters of the time, Elihu Vedder, Kenyon Cox, and Abbott Thayer.

25. ^ Throughout his life La Farge traveled in America's most brilliant intellectual and artistic circles. He accompanied Henry Adams in 1886 to Japan, in 1890/1 to the South Seas and, in 1899 to France, seeing Chartres with Adams (who was to publish Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres in 1903). Widely respected for his knowledge of the history and criticism of art as well as his abilities as a painter and designer, he served as lecturer, juror, and critic for Harvard College, the Art Institute of Chicago, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, and numerous other institutions. In 1899 he gave the commencement address for Yale University and in 1901 was awarded the University's honorary Doctorate, followed by a similar degree from Princeton in 1904. For insight into his critical abilities see John La Farge, Considerations on Painting: Lectures Given in the Year 1893 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1895, repr. 1969).

26. ^ Waern 1886; Cortissoz 1911.

27. ^ Traditional methods of glass painting presumed painted surfaces; extant painted and leaded windows can be dated shortly before the year 1000. Numerous references exist to painted windows from centuries earlier. The early 12th-century treatise on stained glass, the oft-cited text of Theophilus (a pseudonym) describes in detail different strengths in the application of vitreous paint. The best references are still Louis Grodecki's scholarship. See his chapters in Vitrail, Grodecki 1977, and Grodecki and Brisac 1984. For Theophilus see Hawthorne and Smith 1963.

28. ^ See, for example Gresham House, also known as Bishop’s Palace built between 1887 and 1892 in Galveston Texas. Colonel Walter Gresham was a builder of railroads in the south west and also served in the Texas Legislature.

29. ^ Riordan 1881, p. 62; line drawing of window on p. 61.

30. ^ La Farge stated "I also painted the glass very much and carefully in certain places so that in a rough way this window is an epitome of all the varieties of glass that I have seen used before or since." 1894 Report to S. Bing (p. 9) quoted by Cecilia Waern, "John La Farge, Artist and Writer," Portfolio 26 (1896): 54; Raguin 2008, p. 192-94.

31. ^ See above, note 22.

32. ^ The Morse Gallery of Art, Winter Park, Florida, 1885; McKean 1980, fig. 47.

33. ^ Duncan 1980, fig. 8. The painting was made popular via its inclusion in many illustrated texts at the turn of the century, for example, Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, The Story of Jesus Christ: An Interpretation (Boston, 1898), 36.

34. ^ Duncan 1980, fig. 7.

36. ^ Duncan 1980, pp. 105-112. See for fullest documentation, and evidence that Bing's first name was Siegfried, not Samuel, see Gabriel P. Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 [Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service] (New York, 1986), esp. 44-79, and Idem., "S. Bing in America," The Documented Image. Visions in Art History, Gabriel P. Weisberg and Laurina S. Dixon, eds. (Syracuse, 1987), 51-68.

37. ^ Hammond 1978, pp. 216-40; Raguin 2008, pp. 227-29. Tiffany also fabricated a window designed by Ernest E. Simmons, installed in 1892. Hammond 1978, pp. 241-55. Raguin 2008, pp. 357-58.

38. ^ The window is based on Longfellow's poem Hiawatha. It was purchased by the St. Louis County Women's Auxiliary and donated to the Duluth Public Library. Duncan, 1980, fig. 4.

39. ^ Robert Koch, Louis C. Tiffany. Rebel in Glass (New York, 1964 2nd ed. 1966); Masterworks of Tiffany. Louis became a design director of Tiffany & Company on the death of his father. A number of designs appear in both glass windows by Tiffany Studios and enamels by Tiffany & Company, such as the Four Seasons (in Masterworks of Tiffany, p. 133, fig. 54).

40. ^ For the glass object in 19th-century France, see Janine Bloch-Dermant, The Art of French Glass 1860-1914 (New York, 1974); William Warmus, Emile Gallé. Dreams into Glass [exh. cat. The Corning Museum of Glass] (Corning, New York, 1974); Alastair Duncan and Georges de Barth, Glass by Gallé (New York, 1984).

41. ^ See Wilson H. Faude, "Associated Artists and the American Renaissance in the Decorative Arts," Winterthur Portfolio 10 (1975): 101-30.

42. ^ Harrison 1884, p. 343.

43. ^ Harrison 1884, p. 343.

44. ^ The disassociation occurred in 1883. Harrison 1884, p. 343. Harrison states "The original scheme of the enterprise was continued under the name of Louis C. Tiffany and Co., its offshoot retaining the impersonal title of Associated Artists as better suited to the requirement of an enterprise under feminine control. Of these artists themselves it is permitted me to say little." She discusses, in detail, however, the production of the Associated Artists, including the work of Ida Clark, Rosina Emmett (who designed windows as well), Mrs. Wheeler and Miss Dora Wheeler. Their production was in a variety of materials scaled from the highly expensive to common chintzes, cottons, and even Kentucky jean and denim "so familiar to the eyes of the southerner or the Western people in the common garments of their negro population....Thus it will be seen that the aesthetic housekeeper ambitious to adorn her room of state, the modest mother of a household who can spare this much and no more for a thing of beauty in her home, and the embroiderer seeking fresh fields for the vagaries of her needle, need no more look to sources over the sea for their material” (pp. 345-46).

45. ^ For the ideas and much of the phrasing contained in the next few paragraphs, I am indebted to Patricia Pongracz.

46. ^ Harrison 1884, p. 346.

47. ^ Harrison 1884, p. 346.

48. ^ Wheeler’s works are receiving increased contemporary attention, even to historically based reproductions. A review of her work shows the complex intermingling of Arts & Crafts, American Renaissance, and Opalescent design concepts.

49. ^ For a comprehensive treatment of Tiffany's position refer to McKean 1980. McKean had been a Tiffany Foundation Scholar and resident for a summer at Laurelton Hall and is now trustee of the Morse Gallery of Art, Winter Park, Florida. See also Duncan 1980 and Tiffany Studios [1910] 1972.

50. ^ For an articulate chronology of the Tiffany enterprise as well as an comprehensive analysis of the glass making, see Martin Eidelberg and Nancy McClelland, Behind the Scenes of Tiffany Glass Making: The Nash Notebooks (New York: St Martin’s Press in association with Christie’s Fine Arts Auctioneers, 2001).

51. ^ Waern 1898, pp. 16-21.

52. ^ Waern 1898, pp. 17-18.

53. ^ See exploration of the women making the lamps by Martin Eidelberg, Nina Gray, and Margaret K. Hofer, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Discoll and the Tiffany Girls (London : New-York Historical Society, with D. Giles London, 2007). See also Antiques & Fine Art

54. ^ Leaded shades appeared shortly before 1899, although earlier Tiffany had produced individual gas and electric light fixtures such as those for the White House in 1882, and blown glass lamps about 1894. McKean 1980, 187, figs. 182-200; See, especially Eidelberg, Gray and Hofer, 2007) .

55. ^ The chapel was purchased by Mrs. Cecilia Whipple Wallace, Chicago's "Diamond Queen," and given to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine where it served for about ten years. When Ralph Adams Cram was appointed architect of the cathedral he brought with him design revisions in a High Gothic mode and an outspoken antipathy for Tiffany's work. The chapel was neglected until sometime after 1916 when Tiffany was allowed to remove it in a highly dilapidated state. He reinstalled it in Laurelton Hall where it remained after the liquidation of the estate in 1948, and where subsequently it was damaged by fire. Elements of the chapel were saved and moved to the Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida. The chapel was restored in 1999. McKean 1980, pp. 137-44, figs. 129-38; Duncan 1980, pp. 105-107; Nancy Long, ed., The Tiffany Chapel at the Morse Museum (Winter Park, Florida: Morse Museum of American Art, 2002); Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Elizabeth Hutchinson, Richard Guy Wilson and Jennifer Perry, Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall: An Artist’s Country Estate (Yale University Press, 2006).

56. ^ Tiffany commented publicly on this lack of representation. Louis C. Tiffany, "American Art Supreme in Colored Glass," Forum 15 (July 1893): 621-28.

57. ^ Elisheva Marcus posted a sensitive review of the exhibition The Lost Museum at the Bode that commemorated the destruction 70 years earlier.

58. ^ McKean 1980, pp. 57-63, figs. 44-54.

59. ^ Bing had opened a branch of his dealership on Fifth Avenue in the late 1880s, and knew the work of La Farge, Tiffany, and others. He was asked by Henri Roujon, the Director of the Ecole de Beaux-Arts in Paris to report on the 1893 Columbian Exposition, a report published in 1895 as La Culture artistique en Amérique (Bing 1895). See also Idem., "L'Art Nouveau," trans. Irene Sargent, Craftsman 5 (October 1903): 1-15.

60. ^ McKean 1980, pp. 113-31. See above, note 55 especially Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall.