The complex nature of a stained glass window, a structural as well as a decorative element of architecture demands a multi-level fabrication process. Multiple hands are involved, even from the acquisition of suitable materials, which often vary from artist to artist. The evolution of the design, which in almost every case is decided upon though interaction between patron and artist, is tied to the architectural setting. During the opalescent era, when the leaded window was such a dominant aspect of décor, we find highly varied responses to the demand for glass.

Designers within a single studio

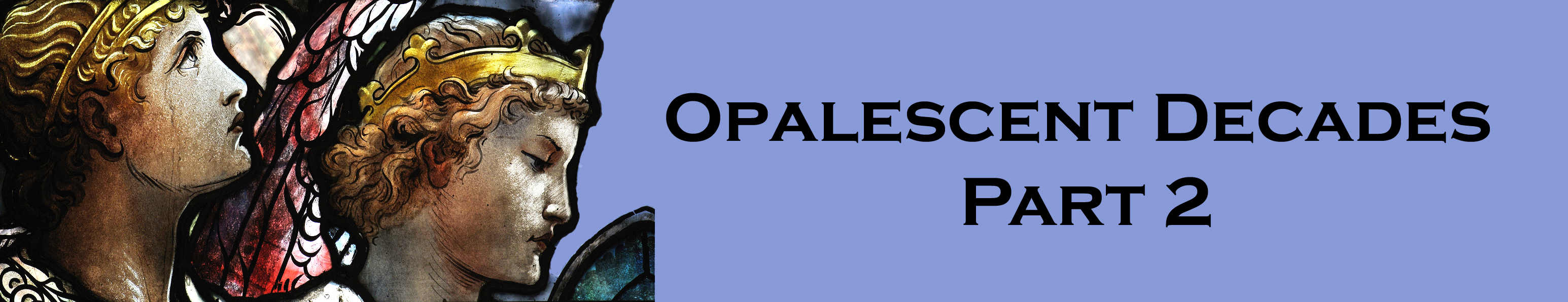

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication, Madonna

of the Flowers, detail, 1899, Arlington

Street Church, Boston. Photo: authorThe earliest windows documented after Louis Comfort Tiffany's personal designs show his predilection for lush expanses of color and a delight in the texture and "glassiness" of the material itself. The Eggplant Window of 1879 is an appropriate example of his personal design.1 An abstract window of about 1880 in the Metropolitan Museum is exuberantly diverse. Its juxtaposition of confetti effects, rippled surfaces, three dimensional jewels, with deep swirls of purple light against blue and amber exploits the great potential of opalescent glass design. These qualities remained constant in the studio's work.

The designers Tiffany employed were of high quality and many later founded their own studios. Maitland Armstrong, who later with his daughter would produce a considerable number of windows, designed many of the works emanating from the Tiffany Studios during the 1880's, for example, John on Patmos in Grace Episcopal Church, Providence, Rhode Island, and the program for St. Columba's Chapel, Middletown, Rhode Island.2 Edward Peck Sperry, responsible for the Bernard and Godfrey window at Harvard, discussed in the essay on Memorials, Rosina Emmett Sherwood, Jacob A. Holzer, and Agnes Northrop were also prominent designers in the studio.3 The studio's most characteristic figural work, however, appears indebted to the influence of Frederick Wilson, an Englishman who came in 1890s and remained for close to thirty years. Wilson's work is visible in the elegant Pre-Raphaelite facial types, with long slender noses, broad foreheads, high cheek bones, and invariably reddish tonality to hair and beard.

Frederick Wilson: integrity of design and diverse fabrication

For most people, the image of Tiffany Studios figural work actually is a window designed by Wilson.4 His characteristic angels with their shimmering multihued opalescent wings populate houses of worship across the country. 5 One of Wilson’s first associations was with the studio of Alfred Godwin in Philadelphia. By 1893, when several window designs were included in the World’s Columbian Exposition, he was supplying designs for Tiffany. Given the wealth of recent publications on the Tiffany studios, I would like to probe the status of this designer within the marketplace. Who, indeed, owned a design and how was the originator reimbursed, especially for multiple uses? A small watercolor sketch for the Beatitudes windows at Arlington Street Church, now in the Metropolitan Museum is signed “Copyright 1905 by Frederick Wilson.” The fabrication was by Tiffany Studios using Wilson’s sketch as the basis for six windows from 1905 through 1929. The program at Arlington will be discussed later in this essay. Wilson left New York for Los Angeles in 1923. The later windows are quite different in color selection, type of glass, and painting. One wonders about the extent of Wilson’s involvement each application of the design or if he were paid a residual fee for its reuse.

Wilson’s designs were also produced by the Gorham Company, best known, perhaps as manufacturers of silverware, but which also supported an ecclesiastic design wing.6 A number of images of executed windows and cartoons in the company archives are marked “The Gorham Co.” on the left side and "copyright Frederick Wilson," on the right. Wilson, apparently, was able to market his designs to other companies while supplying designs to the Tiffany Studios. The Gorham windows, displaying all the characteristics of opalescent color and sophisticated craftsmanship, could easily be, and frequently have been mistaken for the work of the Tiffany Studios. Gorham’s 1911 brochure advertising its Ecclesiastical Department contains a series of windows designed by Wilson. Among them, those for the Thompkins Memorial Chapel, Masonic Care Community, Utica, New York, include David and Jonathan before King Saul and, by Wilson and Edward B. Herrick, three windows entitled Faith, Hope, and Charity.

Painted as well as opalescent techniques

Frederick Wilson, designer,

unidentified studio, fabrication,

Wycliffe and Anselm, 1912,

St. John’s Chapel, Episcopal

Divinity School, Cambridge MA.

Photo: authorWilson’s designs were also fabricated with cathedral glass – or installations that

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios, fabrication, 1902,

First Presbyterian Church,

Pittsburgh. Photo: author mixed cathedral and opalescent without using any of the techniques of plating, three-dimensional inserts, or textured surfaces.7 In 1912, St. John’s Chapel of the Episcopal Divinity School, Cambridge Massachusetts, installed a window based on Wilson’s design depicting Anselm and Wyliffe. The flanking windows were executed, like most of the glass in the chapel, by the London firm of Heaton Butler and Bayne. The meticulously finished cartoons for St. Anselm, and for Wycliffe now in Metropolitan Museum of Art show tour-de-force modeling in gauche. The executed works have suffered considerable paint loss; they are traditional manufacture, paint on pot-metal glass.

Earlier, a much larger installation by the Tiffany Studios for The First Presbyterian Church

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios, fabrication, Angels

(Charles and Isabella Hayes Memorial),

1902, First Presbyterian Church,

Pittsburgh. Photo: author of Pittsburgh presented Wilson’s designs in paint. The church was built in 1903, and all of the sanctuary windows were fabricated by Tiffany save a single window of Christ Teaching by the Lamb Studios. Wilson’s characteristic figural style appears throughout. The deeply contoured folds of drapery, commonly executed in drapery glass, are here carried by painted line. Opalescent glass still appears, noticeably in small background details such as the flowers and leaves at the feet of several angels. Bold linear strokes structure the composition supported by broad areas of relatively .jpg)

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios, fabrication, Isaiah,

First Presbyterian Church, Pittsburgh.

Photo: author unmodulated granular wash. The windows essentially present as a tinted drawing.

Comparison with the single window by the Lamb Studios in First Presbyterian reminds us of the capabilities of lead and adroit glass selection among the gamut of opalescent varieties of the time. Even without employing three-dimensional drapery glass described by Waern earlier, the Lamb Studios designed varying sized segments to suggest the fall of drapery. The lead lines flow in close parallels or in sweeping loops to mimic the .jpg)

J & R Lamb Studio, Christ

Teaching, detail upper level, Angels

(Neville, Oldham and Crain Memorial),

1902, First Presbyterian Church,

Pittsburgh. Photo: authorsmooth expanse across arm or thigh and the bunched folds in between. Paint is confined to the flesh areas. The colors of mottled blue and green suggestive of incorporeal bodies echo the hues of the surrounding sky.

Many sources of design

The complex eclecticism of this era impressed critics of the time, such as Riordan who observed that practically "all our designers" were employing "endless combinations" of

Kazak rug once owned

by John La Farge, Central

Congregational Church,

Newport, Rhode Island.

Photo: author

John La Farge, wall painting,

1880, Central Congregational Church,

Newport, Rhode Island. Photo: authorabstract ornamentation and geometric designs of medieval, Arab, Japanese, and Renaissance traditions.8 Van Brunt, one of the architects of Memorial Hall, Harvard, praised the artistic context of Trinity Church, Boston, were "the painter had no reason to yield anything of his freedom to archaeological conventions; he

John La

Farge, opalescent

window, 1880,

Central

Congregational

Church, Newport,

Rhode Island.

Photo: authorwas left at liberty to follow the same spirit of intelligent eclecticism which had guided the architect."9 Patricia Pongracz has assembled documentation on the many sources, predominantly from pre-Renaissance Italy that inspired much of the production in Tiffany’s ecclesiastical furnishings.10 A continued example of these trends is the interior of Newport's Congregational Church designed in 1880 by John La Farge. The motif employed over the side galleries is the pattern of a Kazak rug once owned by the artist.11 The ceiling of the nave is divided into rectangular bays also patterned after Middle Eastern carpet designs. The altar shows a stronger influence of Early Christian mosaic and tile work, as do the patterned windows of white and blue

Maitland

Armstrong designer,

Tiffany Studios

fabrication, Memorial

to Elizabeth

Stuyvesant King,

c. 1885-1886,

St. Columba,

Middletown, Rhode

Island.

Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

John La Farge,

painted window, 1880,

Central Congregational

Church, Newport, Rhode

Island. Photo: authorglass with an overlay of gold geometric design. These windows alternate with opalescent windows adorned with jeweled inserts and inspired by Islamic geometric pattern. 12

Cosmatesque pavement, 14th

century, Basilica of St. John Lateran,

Rome. Photo: Michel M. Raguin

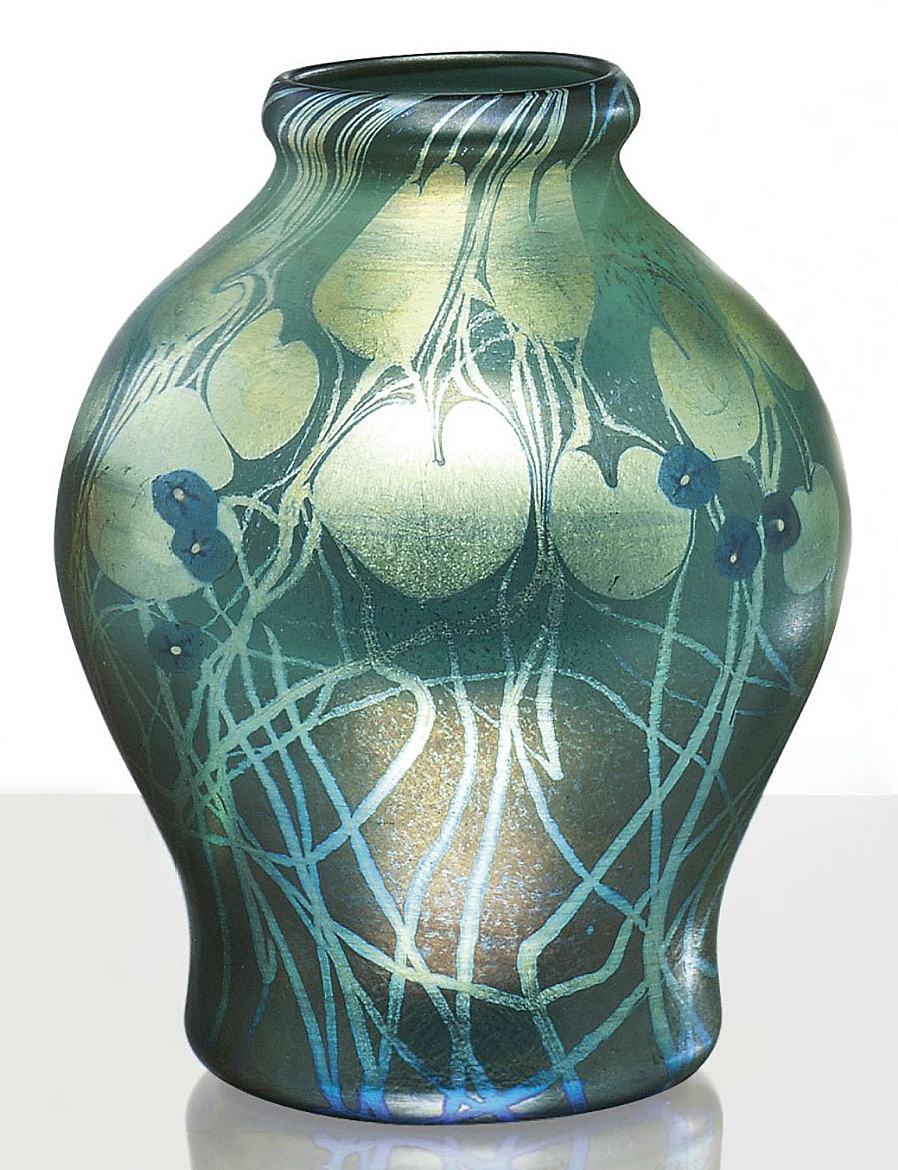

Although the opalescent era may have incorporated 19th-century painting traditions and Renaissance pictorial models, it also valued medieval concepts of decoration. Tiffany's fabled Favrile glass with its metallic opalescent sheen was inspired by the oxidation he observed in the Cesnola collection of Cypriot glass objects in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A Tiffany production of 1897 is actually labeled Cypriote Vase.13 His use of architectural decoration evoked the art of such medieval sites as Cividale, and

Jacob Adolf

Holzer, designer,

Tiffany Studios

fabrication, chandelier,

1893, from World

Columbian Exposition,

Church of the

Covenant, Boston.

Photo: authorLa Farge's imagery was as much Early Christian as it was High Renaissance in its emphasis on symbol, pattern, and integration of architectural and window space.14 One need only look at the medievalizing patterns of stained glass of the era, such as Maitland Armstrong's windows at the Chapel of Saint Columba

Votive crown of King

Recceswinth, Spain, before 672,

National Archeological Museum

of Spain, Madrid. Photo: Manuel

Parada López de Corselas.

ARS SUMMUM , Middletown, Rhode Island, executed by Tiffany and company. The great chunks of mounted and faceted glass recall the cabochon mounted borders of the 9th-century Lindau Gospels,both in their density of color and their patterned settings.15 One also sees the mosaic patterns of the 14th-century Italian Cosmati reflected

Maitland Armstrong designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication, Memorial

to Caroline Howard Clark,

c. 1885-1886, St. Columba,

Middletown, Rhode Island.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinin the mosaic and window designs of Tiffany's art. The huge lantern of bronze and glass in the Church of the Covenant, Boston, Massachusetts is typical of the studio's understanding of richly decorative forms. It was designed by Jacob Adolf Holzer for the Tiffany Chapel at the Columbian exposition in Chicago.16 The structure evokes ancient goldsmith work, Islamic hanging lamps, and Visigothic votive crowns, such as the crown of King Recceswinth in Madrid. The 7th-century crown in Madrid, like the Boston lantern, is suspended by a set of ornate chains, and has a jeweled cross hanging below it.17

Unity in the arts

It was, indeed a time of the unity in the arts. Such has been the focus of a number of exhibitions, such as The Quest for Unity at the Detroit Institute of Arts.18 La Farge was represented in the exhibition by his 1880 oil of the Visit of Nicodemus to Christ the composition first having been painted as a mural in 1878 for the nave of Boston's Trinity Church and later executed in stained glass for the Church of the Ascension in New York in 1883-85.19 The image thus spanned the mediums of large-scale mural, oil on canvas, and stained glass. In the exhibition the nobility of La Farge's figures matched those of Augustus Saint-Gaudens's work in sculpture; the sculptor and painter had collaborated on several commissions.

Arlington Street Church, Boston, and the art of its time

.jpg)

Daniel Chester French,

Allegories of Music and

Poetry, 1904, bronze doors,

Boston Public Library,

Boston. Photo: author

Arthur Gilman, interior, 1859,

Arlington Street Church, Boston.

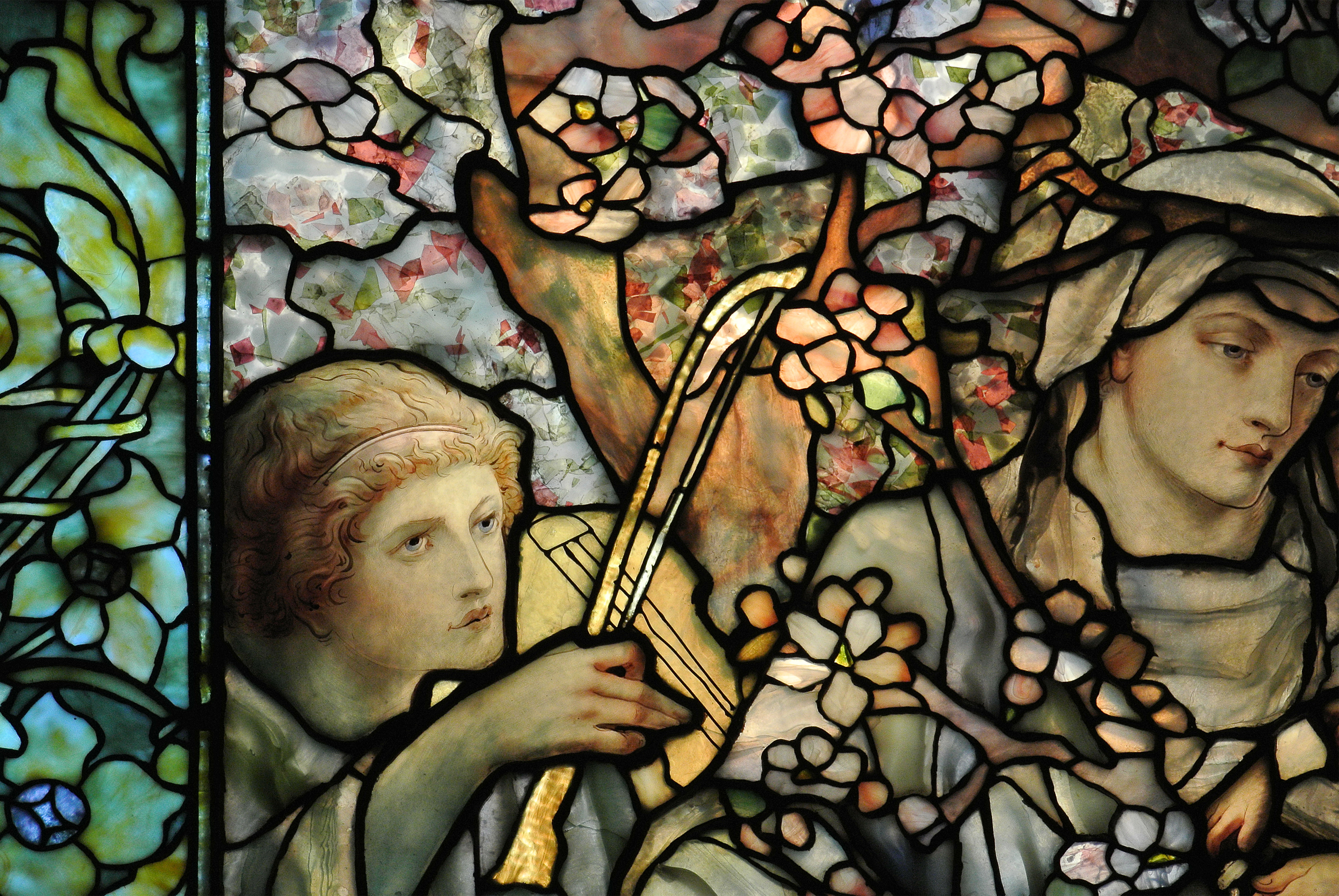

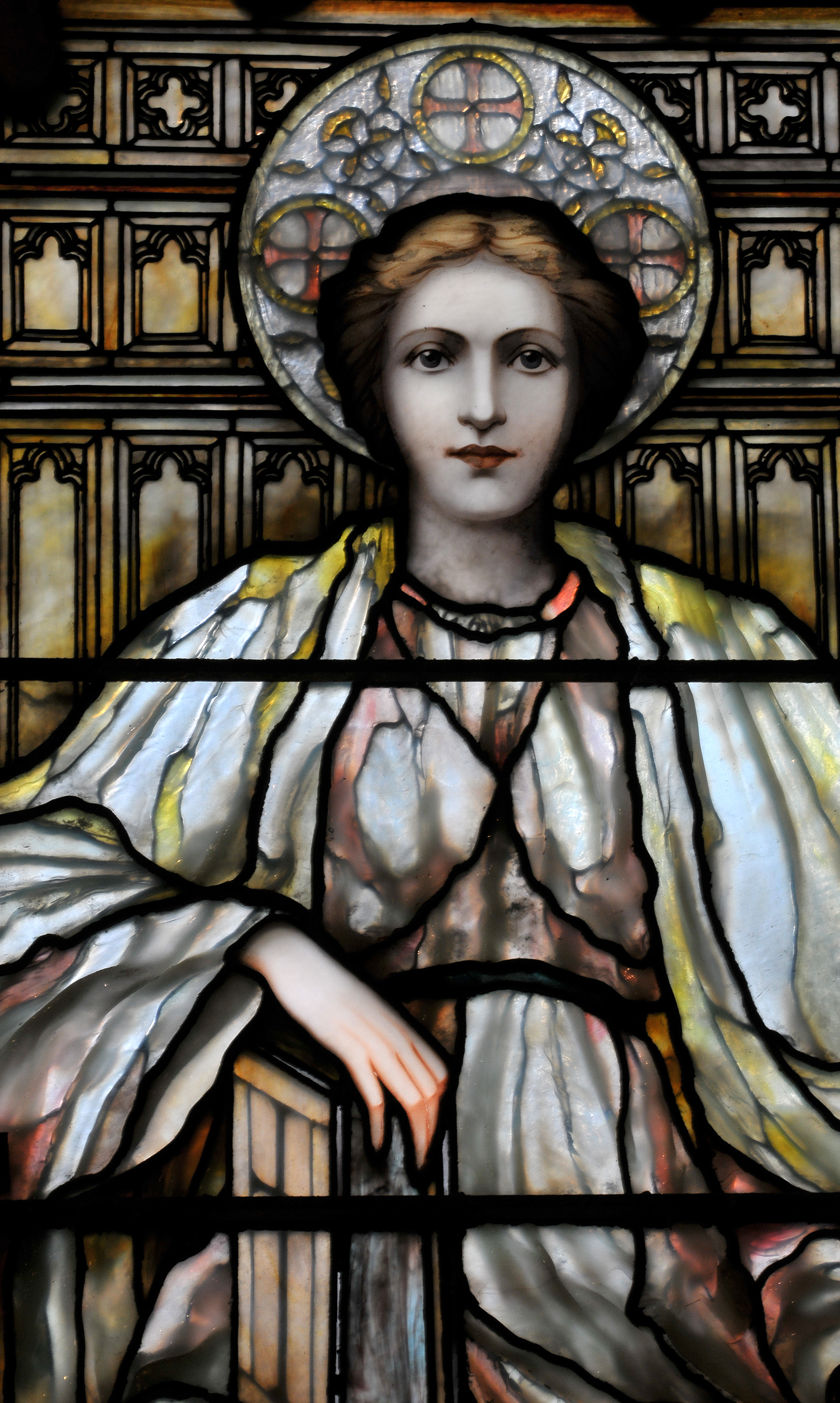

Photo: authorThe windows of Arlington Street Church [See Appendix] by Tiffany Studios exemplify

Frederick Wilson,

designer, Tiffany Studios

fabrication, Beatitude:

Blessed are the Meek,

1904, Arlington Street

Church, Boston.

Photo: authorthe striving for unity within the building and with the formal and ideological convictions of the congregation. Wilson’s 1905 sketch, mentioned earlier, served as the basis for the upper windows. Six majestic figures represent the Beatitudes, the blessings described by Christ in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5:1-11). The uplifting and universal message resonates with the Unitarian ethos of inclusion. Each window presents a central female winged figure flanked by children. In the window Blessed Are the Meek a decorous woman cradles stalks of grain and grapes with their vine leaves in a cloth. At her sides the two children/angels hold palms and decorative shields. The swirling draperies, the noble proportions of the woman, and above all, the monumental import of the image link the design to allegorical figures by Daniel Chester French for the great bronze doors of the Boston Public Library installed in 1904.20 Like the Beatitudes, the Library's figures are allegorical, representing Truth .jpg)

Frederick Wilson, designer,

Tiffany Studios fabrication, Madonna

of the Flowers, 1899, detail, drapery

glass, Arlington Street Church,

Boston. Photo: authorand Romance, Knowledge and Wisdom, and Music and Poetry, the single human figure swathed in its flowing draperies conveying the aesthetic and emotional import of the allegory. The three

Daniel Chester French,

Allegory of Music, detail, 1904,

bronze doors, Boston Public

Library, Boston. Photo: author dimensional folds of Tiffany’s drapery glass suggest the undulations of the bronze relief.

As in painting, so in glass

Tiffany's designers, like La Farge, and a host of others, sought to bring the stained glass of the period more into alliance with contemporary painting. One need only compare the Arlington Street Church's windows with Thomas Wilmer Dewing's 1887 painting The Days now in the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford.21 In both Wilson's and Dewing's compositions, the figures are pushed to the narrow space at the front of the picture plane. The full attention of the viewer concentrates on the heavy folds of drapery cloaking the tall forms and acting as foils for the languidly exposed arms, necks, and oval faces. Dewing's exploitation of the dense curtain of foliage to isolate the figure and enhance the decorative planar effect of the frieze of young women is echoed by Tiffany's dense background colors. Although incorporating realistic depictions, the paintings on canvas and glass integrate the human figure into a pattern of line and color, striving for a unity of pictorial effect.

Arthur Gilman, molding detail,

1859, Arlington Street Church,

Boston. Photo: authorThe allegorical nature of Dewing's and Wilson's imagery is also similar. Dewing drew his inspiration from a poem by Ralph Waldo Emerson, but the great parade of somber young women might evoke Hesiod's description of the Muses, a classical procession honoring Athena by the maidens of Athens, or even a dramatic presentation by the students enrolled in the recently founded women's colleges such as Vassar in 1861 or Wellesley in 1870. The images are comprehensible on many levels, even without knowledge of the specific iconographic reference.

The church had been designed by Arthur Gilman in 1859 in a Georgian mode and

Frederick Wilson,

designer, Tiffany

Studios fabrication,

Beatitude: Blessed are

those who are Defiled,

(Osgood Memorial)

1929, Arlington Street

Church, Boston.

Photo: author loosely patterned after Boston's King's Chapel built a century earlier. Although of a glazing style totally unknown at the time of the building's construction, and even more alien to the 18th-century architectural inspiration, the windows integrate themselves into the interior space with surprising success. The Corinthian columns and sculptured moldings include designs of acanthus leaves. Tiffany repeated the leaves in the extremely wide borders of the windows, thus linking the windows' motifs to the fabric of the building. A movement around the window and upward, following the architectural thrust, is achieved by the subtle gradations of color from warmer tones in the lower borders to cooler hues at the apex of the window. This same format is repeated in the very last windows installed, exemplified by the Osgood Memorial window of 1929.

Jacob Adolf Holzer, Tiffany’s designer of windows and mosaics

Jacob A. Holzer,

designer, Tiffany Studios

fabrication, Faith: Abraham

leaves Ur, (Sarah Jane

Houghton Memorial) 1885,

Church of the Covenant,

Boston. Photo: authorJacob Holzer, like Wilson, was an immigrant. Originally from Switzerland, he worked independently and then joined Tiffany studios. Windows of the Church of the Covenant, Boston, exemplify how a complete “Tiffany interior” could combine different figural styles and color palettes according to the designers. Edward Peck Sperry and Frederick Wilson also designed windows, discussed in the essays on Museum and Church, and on Memorials. Holzer designed a series of three representing the virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity for the north wall. Abraham leaving Ur (Genesis 12:1) carries the inscription: “By faith Abraham went out not knowing whither he went.” The series is sometimes referred to as the sunset windows given that the foregrounds are composed of darker hues against which the sky’s streaky opalescent of yellow, blue and pink evokes the sun setting (or rising). Holzer designed many mosaics for the studio, as well as the great chandelier for the World’s Columbia Exposition, mentioned earlier.

Holzer continued to produce after he left Tiffany. A large commission appears in the Central

Jacob A. Holzer, designer,

Dufner & Kimberly Co., fabrication,

The Heavenly Jerusalem, 1907,

Central Congregational, Providence,

Rhode Island. Photo: authorCongregational Church, Providence, Rhode Island, erected

Jacob A. Holzer, designer,

Dufner& Kimberly Co., fabrication,

The Heavenly Jerusalem, detail of

St. John and the angel, 1907,

Central Congregational,

Providence, Rhode Island.

Photo: authorbetween 1891 and 1893 after designs by Carrière and Hastings of New York. The firm, operating between 1885 and 1929 was one of the preeminent proponents of Beaux-Arts style in the United States. Earlier Carrière and Hastings had completed the massive Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine Florida, embellished with windows from

Dufner & Kimberly Co.,

New York, leaded table lamp,

1905-1911, Photo: James

D. Julia Auctioneers online,

December 1-2, 2010. the Tiffany Studios, discussed later in this essay. It would soon undertake New York’s iconic Public Library which would occupy the firm from 1897 through 1911. The opalescent windows in the Providence church were installed over time, most designed by Holzer. Two huge scenes dominate the sanctuary. The window Let there be Light, showing a circle of angels, is signed “copyright J. A. Holzer 1908.” Opposite, St. John’s Vision of the New Jerusalem is similarly inscribed, but with the date of 1907. Also noted is the name of the fabricator, Duffner & Kimberly of New York, well known for their manufacture of leaded lamps that paralleled the production of the Tiffany Studios. 22 Duffner & Kimberly, typical of many studios, were open to fabrication of work by designers of leaded and painted windows on an individual basis. J. Gordon Guthrie, discussed in the essay of “Arts & Crafts” was the designer of a window produced in 1911 for Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, Kansas City, Missouri 23

Maitland Armstrong

D. Maitland

Armstrong, Faith,

c. 1914, Memorial to

Charlotte Sturdivant

Vaill, Trinity Episcopal

Church, St. Augustine,

Florida.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Maitland Armstrong was a member of Associated Artists with Tiffany from at least 1881 before opening his own studio in 1887.24 Like John La Farge, Armstrong was a painter in the first half of his life, producing carefully crafted landscapes of the Hudson River region and of Italy. He was an intellectual, holding a law degree and appointment to governmental posts of United States Consul to the Papal States, then Consul General to Rome. In 1872 he made the decision to return to the United States and devote himself to painting as a full time activity, but by the first years of the following decade abandoned the "fine" for the applied arts. Helen Maitland Armstrong, the artist's daughter was designing windows as early as 1894 and later became a partner in the firm.25 The links to La Farge's pattern of development are extremely close, albeit with somewhat less of the "genius" about it. Armstrong, like La Farge was a painter, predominantly of landscapes, who saw a potentially rich market in the business of interior design. He entered the field by collaborating with craftspersons and, like La Farge, at first did not fabricate windows in his own studio, but in the studio of two English glaziers, John Calvin and Thomas Wright.26 Armstrong, unlike La Farge, however, typically associated with other designers, first with the Associated Artists organized by

D. Maitland

Armstrong, Angel,

1897, Memorial to

Emeline Forber

Cheeseborough, wife

of Thomas P.

Cheeseborough,

All Souls Episcopal

Church, Ashville,

South Carolina.

Photo: author Tiffany, and then with his daughter Helen. A window depicting Faith, about 1913, in St. Augustine Florida demonstrated the painterly approach to in the flesh areas by the studio.

Maitland Armstrong at All Souls Episcopal Church in Ashville, South Carolina

Armstrong’s commission for All Souls Episcopal Church in Ashville, South Carolina typifies a wealthy client and the complex possibilities of opalescent glass. The church is adjacent to the massive North Carolina estate, Biltmore, built in 1889 by George W. Vanderbilt, the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt. A product of collaborative work of Fredrick Law Olmsted, landscape architect and Richard Morris Hunt, architect, Biltmore village also included a chapel. Vanderbuilt supported its construction and all costs until his death in 1914. Designed by Hunt, its windows by Armstrong commemorate many of the individuals associated with Biltmore. The window honoring the architect presents Solomon ordering the plans of the Temple, a theme close to that used by Burne-Jones for a window in Trinity Church in Boston. In this memorial of an architect through the depiction of his biblical counterpart, we read the phrase, “For Glory and for Faith.” The marble sheen of the façade of the temple and glowing colors in the figures’ robes exploit the painterly qualities of opalescent glass.

Ponce de Leon Hotel, St. Augustine, Florida

Tiffany Studios, supervision,

D. Maitland Armstrong, Dining Hall,

Ponce de Leon Hotel, now Flagler

College, Florida, 1887, St. Augustine,

Florida. Photo: authorA discussion of the Ponce de Leon Hotel, St. Augustine, Florida, now Flagler College, allow us to focus of the breadth and complexity of the era. Armstrong very probably designed for this installation; at the very least, we know that he was the supervisor of the installation.27 The hotel, a project of the millionaire developer and co-founder of Standard Oil, Henry M. Flager, exemplifies the synergy between the development of glazing and taste in building. Just as the new opalescent glass combined both cutting edge technology and nostalgic eclecticism, the hotel was inspired by architecture of the Spanish Renaissance, and also stands as one of the pioneer installations of poured concrete, used throughout. It was also completely .jpg)

Tiffany Studios,

supervision, D. Maitland

Armstrong, Dining Hall,

Ponce de Leon Hotel,

now Flagler College,

Florida, 1887,

St. Augustine,

Florida. Photo: authorwired for electricity, facilitated .jpg)

Tiffany Studios, supervision,

D. Maitland Armstrong, Dining Hall,

detail, Ponce de Leon Hotel, now

Flagler College, Florida, 1887,

St. Augustine, Florida. Photo: authorthrough Flagler’s association with Thomas Edison. The building was lavishly decorated with mosaics, murals, stucco, and sculpture as well as leaded windows. At the center of the hotel, stands a great rotunda crowned by a dome. The rotunda received murals by George W. Maynard, one of the artists who supplied murals for the icon of Beaux-Arts classicism, the Jefferson Wing of the Library of Congress. Leading from the hotel’s rotunda, an oval-shaped dining hall allows for a seating of 700 guests. The walls and ceiling murals display Renaissance urns, garlands, vines and heraldic badges depicting the history of St. Augustine. Tiffany’s opalescent windows in golden tones both pulsate and sparkle, illuminating painted imagery and inhabitants.

Popularity of decorative windows

Lamb Studios,

Wisdom Enthroned,

detail Wisdom, 1896

(Florence Humbert

Memorial) Church

of the Messiah,

Rhinebeck, New

York.

Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

Tiffany Studios,

millifiori-vase,

Photo: Philip Chasen AntiquesGlass, as decorative insert into window lights, as leaded lampshade, image in a place of worship or skylight in a court of justice, had become ubiquitous. For the very first time, American large-scale, architectural installations were linked aesthetically and materially to the always important art of glass objects. America had a very long-standing tradition of quality production of the glass vessel, from the early days of the Sandwich glass on Cape Cod, through the beveled and etched glass of the 19th century.28 It is significant that Tiffany, the most successful firm of this era, was equally at home with the production of the glass object, such as leaded lampshades and molded and blown vases as he was with the architectural

Louis Comfort Tiffany &

Co. Daffodil leaded glass table

lamp, designed by Tiffany's

head designer, Clara Driscoll,

c. 1899-1920, private

collection, New York City.

Photo: Telome4 installation of a window. The feel of the glass was the same, richly variegated colors, sinuous forms, and the unmistakable milky colors and pearly sheen of the surface. The actual three-dimensional quality of the windows likened them even more to the "object." The intricate plating and leading structures, adopted by many the studios of the era created the solid weight of sculpture. The use of textured glass, even in manipulated folds, evoked techniques of bas-relief and fused the opalescent window with the carved reliefs in wood and stone of the buildings they adorned. Their colors and "glassiness" linked them with the glass objects set within those buildings. Their incorporation of Renaissance style in its emphasis of the human form to convey both allegorical and historical subject matter echoed contemporaneous expression in painting and illustration.

European followers

The American experiments that produced the verre américain as it was known in Europe, had a considerable impact on the progressive centers of Europe. Paris, Nancy, London, Vienna, Barcelona, and Prague soon produced windows incorporating the American material and its decorative context. The American style propagated via the International Exposition as well as commissions for Europe, such as that of Tiffany for Bing's "Salon de L’Art Nouveau" of 1895. La Farge was the first recognized, his work being exhibited in the Paris Exposition of 1889 and receiving serious review by Edouard Didron.29 Tiffany exhibited in Brussels at the Libre Esthétique in 1897, and with Bing at his 1899 Grafton Gallery show in London.30 The Four Seasons window was among Tiffany's entries at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, for which he received a Gold Medal and was decorated by the French with order of a chevalier of the Legion of Honor, as La Farge had been some years earlier.31

France

Eugène Grasset,

designer, Félix Gaudin,

fabrication, Le Travail par

l'Industrie et le Commerce

enrichit l'Humanité, 1900,

Chambre de Commerce,

21 rue

Notre-Dames-des-Victoires,

Paris.

Photo: courtesy

Jean-François Luneau The context of interplay between glass object and window was similar in France where the Daum and Gallé factories produced vessels that rivaled the Tiffany art glass line.32 Established artists such E. Champigneulle incorporated the American products in art nouveau windows such as his allegories of the Four Seasons and of Day and Night of 1896 created for a private home in Châlons-sur-Marne.33 It was only in the first decade of the 20th century, however, that the full gamut of American techniques and glass varieties appears to have been incorporated in European buildings. The International Exposition of 1900 in Paris functioned as a catalyst for the European as well as the American creator. A much admired window Le Travail par l'Industrie et le Commerce enrichit l'Humanité(The Work of Industry and Commerce Benefits Humanity) graced the pavilion of Chamber of Commerce. Eugène Grasset produced the cartoon and the fabrication took place in the studio of Félix Gaudin.34 After the close of the Exposition, the window was transferred to the Chambre de Commerce, Salle des Séances, 21 rue Notre-Dames-des-Victoires, Paris. Closely patterned on pictorial models of the time, the panel combines opalescent and traditional glazing techniques. A young girl symbolizes Industry, a man with a hammer, Work, and a seated woman holding ledgers and Mercury's staff personifies Commerce. The figures incorporate traditional European antique glass defined by paint, but the verre américain dominated the landscape of flowers and foliage against a horizon filled with multi-hued smoking factories. Georges de Feure also exhibited a window in the Paris Exposition, a dramatic female swathed in flowing robes apparently gathering fruit from a tree.35 De Feure’s window of a lady with a fashionable hat, dated 1901-1902 is now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Although there appears to be no milky opalescent glass in the window, the shifting hues within a single piece of glass suggests its influence.

Jacques Gruber of Nancy

American influence was widespread in art nouveau expressions , an international movement with great strength in Nancy. The city’s extant windows attest to the interest in glazing as a major decorative element in public buildings and in private homes.36 Glass in architecture was deeply associated with the art glass vessel, one

Émile Gallé, vase,

1890-1900, private collection,

about 1905.

Photo: Michel M. Raguinof Nancy’s most important products. The enterprise of Emile Gallé, who transformed his

Jacques Gruber, Glass

Making, 1907-1908, Chamber

of Commerce and Industry,

Nancy. Photo: C. Rose,

Inventaire Général de

Lorraine.father’s faience company into an international center for art nouveau cut glass, and the studio of Jean Daum, found in 1878, were major forces in the art of decorative glassware.37 Jacques Gruber's first public exhibition in Nancy consisted of three works in pastel and eight works in glass he produced in collaboration with Antonin Daum, Jean Daum’s son and inheritor.38

Jacques Gruber may stand for many as typifying the use of American opalescent methods. He produced figural and decorative work using textured glass, opalescent varieties, and even the multiple plating pioneered by the Americans, termed in French verres superposés. As in America, the stained glass makers also designed fire screens, furniture, and above all glass vessels. Gruber’s series of windows installed in 1909 in the ground floor of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry building in Nancy reflect the influence of Grasset's window at the Exposition Universelle. Each window represents a major industry of the region, one being that of the production of glass. A worker pulls molten glass out of a glowing oven, a theme allowing the artist to exploit the multiple color shifts of the glass to create illusions of cast and reflected light.39Gruber’s Lily Pond window, about 1912, is now at Virginia

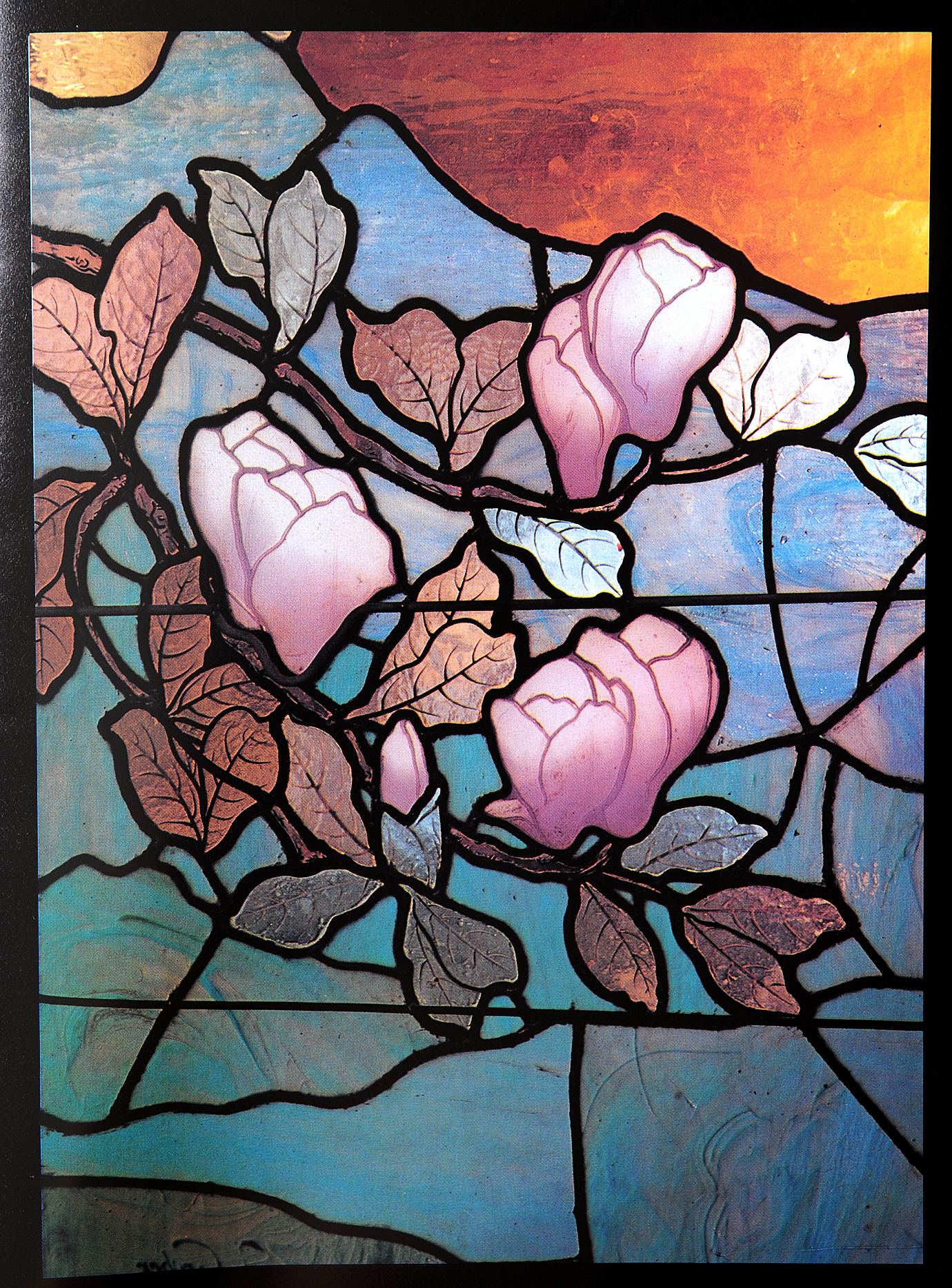

Jacques Gruber,

Magnolias, detail, made for

house constructed in

1904 for L. Weissen,

Nancy. Photo: D. Bastien,

Inventaire Général

de Lorraine.Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Striated blue and green glass define the leaves while the lilies transition from white interior to blue reflection, accented at the center by yellow silver-stain, Three-dimensional blue circles enliven the hanging foliage. Gruber’s window featuring magnolias for a private home in Nancy constructed in 1904 for L. Weissen, shows the subtle swirls of color found in the glass at St. Columba’s Church, Middletown of 1885. The design recalls as well the profile of leaves and flowers familiar from Gallé’s vases.

Opalescent glass and architecture

Glass was a ubiquitous architectural element of the time. There was no possibility that around the turn of the century an architect could design a building without consideration given to the leaded window. Sometimes beveled and made of simple etched or frosted glass, or even unworked segments of machine-rolled glass, glass in the decorative schema was a reality. It is not surprising, then, to see train stations, banks, court houses, libraries, and public auditoriums constructed to include stained glass.40 Virtually any city in America at the turn of the century could furnish examples of architectural installations of stained glass in commercial and domestic buildings.

San Francisco as exemplar

San Francisco, however, retains some of the most impressive examples of this type, a number recently restored. In the period following the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, many buildings were constructed in the American Renaissance mode. One of the city's most prolific stained glass studios at that time was the United Art Glass Company, owned by Harry and Bert Hopps, responsible for the dome of the Garden Court of the Sheraton Palace Hotel, the City Hall, Olympic Club, the majority of the glass domes and ceiling of Cypress Lawn (Colma), as well as smaller installations such as restaurants and private homes.41

City of Paris department store of 1909

.jpg)

City of Paris rotunda,

1909, in Neiman-Marcus store,

San Francisco.

Photo: courtesy Peter Talke

Frantz Jourdain, La Samaratine

department store, Paris, 1903-1907.

Photo: red-luxury.comOne of the most spectacular designs was the dome for the City of Paris department

Georges Chedanne and

Ferdinand Chanut, Galeries

Lafayette, Boulevard

Haussmann, Paris, 1912.

Photo: Benh Lieu Songstore, completed in 1909 during the great rebuilding after the earthquake of 1906. It was inspired by the integration of the leaded window into the entire decorative aesthetic of the Grand Magasin of France at the turn of the century. Stores such as La Samaritaine and Les Galeries Lafayette of Paris attracted customers through the opulent interiors dominated by the multi-level galleries and domed skylights.42 The City of Paris building was designed by the French-born architect Louis Bourgeois and French-trained firm of Blakewell and Brown. The glass supplier, however, was the American manufacturer, Kokomo.43 The oval rotunda rises story after story alternating straight and undulating balcony railings. All materials interweave in a blaze of belle- époque opulence. Carried in the volutes of the architecture and reflected in the interlacing patterns of the glass, the color scheme is dominated by

City of Paris dome,

1909, in Neiman-Marcus

store, San Francisco.

Photo: courtesy

Sanfranman59white and gold. Gold leaves that appear against the white ground of the wall echo the white leaves set against gold columns in the translucent dome. Pale yellow rays of glassy light burst from behind the head of the stucco grotesques at either end of the rotunda.44 In 1982 a new store was designed for Nieman Marcus by the architectural firm of Philip Johnson and the City of Paris dome integrated in the new construction. The circular and oblong domes of the Hibernia Bank, designed by Albert Pissis in 1892 shows similar Renaissance-inspired designs of gold and white.

Civic Center of San Francisco

The size and lavishness of the Civic Center of San Francisco were conditioned not only by the need to rebuild after the earthquake, but by its service as one of the principal buildings for the Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915. The City Hall, designed by Arthur Brown, Jr., with its domed rotunda, marble staircase, arched alcoves, fluted pilasters, and figural reliefs, dominates the cluster of buildings.45 The glazing, harmonizing with the Renaissance-inspired design of the building, consists of white glass in intricate lead patterns. A trellis of a diamond pattern is framed by a border punctuated by interlocking trefoil moldings. Located in the upper portion of the window is a linear design of ships under sail set in an architectural frame through which laurel leaves meander. The cool geometric pattern of the design functions as a mutual enhancement of the monochrome gray marble of the interior.

The Olympic Club

Olympic Club,

natorium, San Francisco.

Photo: Blinksternet The Olympic Club, a private club dating from the 1860s, was rebuilt after the destruction

Garden Court, Sheraton Palace

Hotel, San Francisco, 1909.

Photo: Library of Congress of its lavish 1872 building. The pool area, the natorium, clearly evokes the splendor of the architecture of the Roman bath. Corinthian columns supporting a narrow balcony frame a rectangular pool. Above, the glazed domes and lunettes filter artificial daylight creating a bright, soft atmosphere. Like the design of the windows for the City Hall, the glass functions as an element of the architecture and displays a predominantly white pattern with a border of palmettes in pale green against a golden background. The Garden Court of the Sheraton Palace Hotel, evoking more of the central European rococo than Rome, is possibly the quintessential expression of luxury. The architectural function of the window, however, is similar to the pattern of the Olympic Club. Its present form dates from 1909, a vast cage of glass hovering over the 110 by 85 foot room. The great lintel dividing wall from dome is supported by paired marble columns crowned by composite Roman capitals of gold gilt. Above the lintel, half circles with projecting open canopies alternate with the ribs that support the long rectangular central segment of the dome. Crystal chandeliers further intensify the interplay of glass, marble, and gold fragmenting and transmitting multiform impressions of light.

Bardelli’s Restaurant

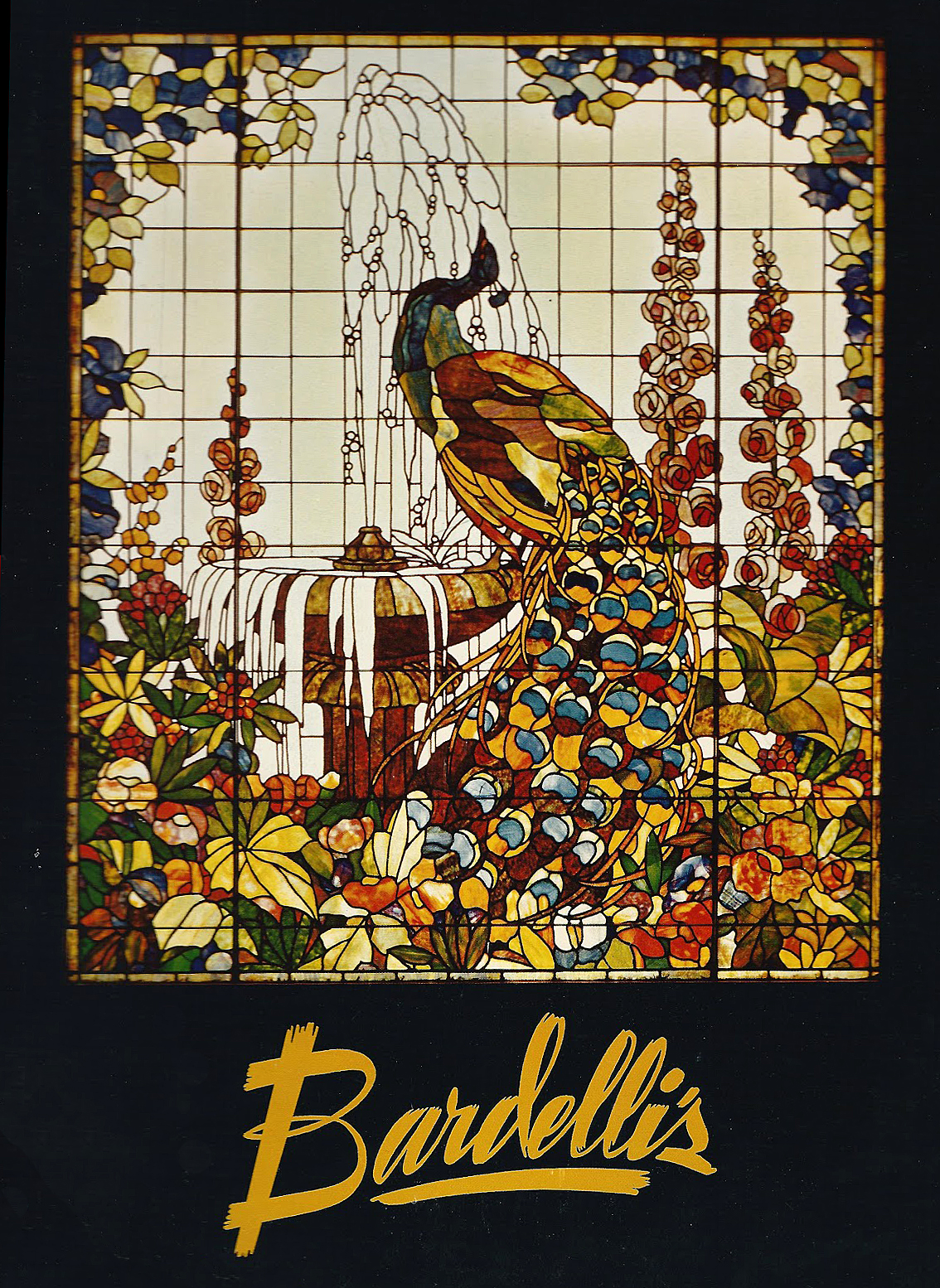

Bardelli's at 243 O'Farrell Street, which closed in 1997, typifies the use of opalescent glass

Menu showing

Peacock window, Bardelli's

Restaurant, 243 O'Farrell

Street, San Francisco.

Photo: Chris Suhrfrequently incorporated into dining establishments of this era. The entrance doors displayed leaded and faceted white glass in a nested arch motif embellished by five linked circles. The client then passed through a small rectangular wind baffle and was surrounded by opalescent glass. Most spectacular was a lavish panel opposite the entrance showing a peacock drinking at a fountain and surrounded by flowers. The glass used is technically conservative, small segments and single panes without plating, suited to the necessity of maximum transmission of light and low maintenance. Side panels of the structure repeated the stylized hollyhocks framing the peacock. Opalescent purple glass grapes dangled in the transom areas and the dome showed a simple leaded geometric pattern accented by colorful bands at the base and across the top. The effect of the glass, although impressive as the client enters, was particularly telling with daylight illuminating the peacock and flowers for the luncheon sitting.

Changing taste and modern preservation

The very lavishness of these settings has endangered their survival. The upkeep of the complex carved, gilt, and colored surfaces demanded extraordinary investment. Over time, these Renaissance palaces fell out of favor as the lean lines of Art Deco and the even sparser embellishment of the Modernist period captured the taste of San Francisco, and the national as a whole. Buildings fell into disuse, or, more disastrously, were renovated to accord with the growing aversion to opulence. Only with the rise of the postmodern era have these great structures reclaimed their importance to owners and developers alike. The intermingling of styles from a variety of periods and the sensual delight in color and texture, indeed, even the confusion of materials and spaces created by the overload of surfaces resonate with the same challenges as those delighting the postmodern designer. The reclaimed turn-of-the-century building now exists side by side with the recently built edifice of faux marble, truncated arcades, and floating pediments.

1. ^ Private collection. Alice Cooney Frehlinghuysen, in Pursuit of Beauty, p. 189, FIG. 6.3; McKean 1980, pp. 51, 56, fig. 42. The window was illustrated via a wood engraving technique in Riordan 1881, p. 234, fig. 5.

2. ^ The Providence window is illustrated in Low 1888, pp. 681, 686.

3. ^ Duncan, 1980, pp. 65-74. For Rosina Emmett Sherwood's cartoon and window of "The Fall", see Coleman 1893b, pp. 488-89. Duncan 1980, p. 159) published the design as by Lydia Emmett. The present location of the window is unknown. The Church of the Covenant, Boston, shows the work of Holzer, Sperry, and Wilson, see Koch 1966.

4. ^ Diane C. Wright, “Innovation by Design: Frederick Wilson and Tiffany Studios’ Stained-Glass Design,” in Louis C. Tiffany and the Art of Devotion, Tricia Pongracz, ed. (Museum of Biblical Art with D Giles Ltd, London, 2012), pp. 137-161.

5. ^ The reuse of similar designs was characteristic. The Wilson/Tiffany choir of angels can be found in slightly modified compositions in the transept of the Church of the Covenant, Boston, the Nativity window in Christ Episcopal Church, Rochester (Duncan 1980, fig. 19); the chancel windows of St. Michael's Episcopal Church, New York, installed 1895 (Sturm 1982, fig. 122); or in the Four Elements window in the First Church Congregational, Cambridge, Massachusetts (the Horsford Memorial window that was set in the building about 1896 when it was the Shepherd Congregational Church, Duncan 1980, fig. 10), and well and many other installations.

6. ^ Brown University Library is the repository for the archives of the company.

7. ^ St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Salt Lake City shows several signed Tiffany windows in typical opalescent execution, The Road to Emmaus and the Annunciation. The window of St. George, signed “Tiffany Studios NY 1916,” however, is a single-layer installation, with background and architectural borders of opalescent, but the figure in cathedral glass modeled via paint and silver stain.

8. ^ Riordan 1881, p. 62.

9. ^ Henry Van Brunt, "The New Dispensation of Monumental Art: The Decoration of Trinity Church in Boston and of the New Assembly Chamber at Albany," Atlantic Monthly 43 (1879): 635.

10. ^ Patricia Pongracz, “Tiffany Studios’ Business of Religious Art” in Pongracz 2012, pp. 50-85.

11. ^ See Jeffery Howe, ed., John La Farge and the Recovery of the Sacred [exh. cat. McMullen Museum of Art] (Chestnut Hill, Boston College Press, 2015).

12. ^ Weinberg 1977, pp. 194-205; color photographs in John La Farge: An American Master 1835-1910 [sale cat. William Vareika Fine Arts] (Newport, Rhode Island, 1989), pls. 20-24.

13. ^ For analysis of the glass making, see Martin Eidelberg and Nancy McClelland, Behind the Scenes of Tiffany Glass Making: The Nash Notebooks (New York: St Martin’s Press in association with Christie’s Fine Arts Auctioneers, 2001).

14. ^ His Japanese influence has been traced by Henry Adams, "A Fish by John La Farge," Art Bulletin 62 (1980): 269-80.

15. ^ Lindau Gospel Book, c. 870, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, Peter Lasko, Ars Sacra (Baltimore, 1972), 65-66, fig. 59.

16. ^ When the exposition closed, Joseph Huntington White donated the lantern to the Church of the Covenant. Koch 1966, p. 5. Holzer was a Swiss-American (1858-1938) who collected as well as designed (Exposition Holzer, Musée Rath, Geneva, May 3-23, 1929).

17. ^ Jeweled crown of King Recceswinth, found in 1858 at Fuente de Guarrazar with a hoard of a dozen votive crowns, Madrid, Museo Arqueologico. Jean Hubert, Europe of the Invasions [trans. of Europe des Invasions] (New York, 1969), 241, fig. 248.

18. ^ Quest for Unity. See also Pilgrim, Murray, & Wilson, 1979.

19. ^ Quest for Unity, pp. 116-17, No. 49.

20. ^ Michael Richman, Daniel Chester French: An American Sculptor [exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art] (New York, 1977), 12, figs. 12-14; contemporary review by Russell Sturgis Jr., "Bronze Doors for the Boston Public Library," Scribners Magazine 36 (1904): 765-68, illus.

21. ^ Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut 1944.328. Doreen Bolger Burke in Pursuit of Beauty, pp. 334, FIG. 9.18.

22. ^Martin M. May, Great Art Glass Lamps: Tiffany, Duffner & Kimberly, Pairpoint, and Handel, (Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2003).

23. ^ Current research of Randal J. Loy, historian of Grace and Holy Trinity Cathedral, Kansas City, Missouri. He reports that Guthrie worked for Duffner & Kimberly between 1905 and 1914.

24. ^ Lynne Ambrosini, Director of Collections, Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati. Her graduate paper written in 1980 contains important research on Armstrong and the position of the fine and the applied arts in the last quarter of the 19th century which she generously shared. See also Robert O. Jones, "Italian Inspiration in Maitland Armstrong's Stained Glass and Mosaics" in Irma B. Jaffe, ed., The Italian Presence in American Art, 1860-1920 (New York & Rome: Fordham University Press & Instituto Della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1992), 97–104 and Ibid., D. Maitland Armstrong: American Glass Master (Tallahassee: Sentry Press 1999). An autobiographic statement, by D. Maitland Armstrong is found in Day Before Yesterday: Reminiscences of a Varied Life (New York, 1920). The work was edited by his daughter Margaret, presumably as a posthumous tribute after Armstrong's death in 1918. The rambling, chatty book contains little information about Armstrong's commissions, a phenomenon presumably reflecting class injunctions about the business of remunerative trade. The reminiscences, reveal, however, rich interrelationships the well-known artists of the day, Saint-Gaudens, La Farge, Stanford White, McKim, even Luc-Olivier Merson, the French stained glass designer, whom Armstrong had recommended for an unrealized commission (pp. 311-13). Merson was later to design the window, The Supper at Emmaus, exhibited in the 1889 Exposition in Paris, (Didron 1889, p. 40) and installed in Christ Episcopal Church, The Bronx (New York). See Sturm 1982, fig. 22, where the window is identified as by Eugène Oudinot. The window was fabricated in the Oudinot studio, but designed by Merson.

25. ^ Robert O. Jones, "Maitland Armstrong & Company: Uncatalogued Windows in the South Reveal Studio's Superb Artistry," Stained Glass 81/4 (1986): 288-93. Armstrong's mother was from Charleston, South Carolina, as were several close relatives, and extant windows appear in the Biltmore House, designed by Richard Morris Hunt for George Vanderbilt and the near-by All Souls Episcopal Church, Biltmore Village, Asheville, North Carolina; Faith Chapel, Jekyll Island, Georgia; and St. Margaret's Episcopal Church, Hibernia, Florida.

26. ^ Jones 1999, pp. 132-36. Calvin and Wright fabricated the window of Wisdom Enthroned by John La Farge for Unity Church,, discussed later in the essay on Memorials.

27. ^ Jones 1999, pp. 94-95, the installation of Tiffany windows for the Ponce de Leon Hotel , now Flagler College, Florida, 1887 was the last of the projects supervised by Armstrong for the Tiffany company.

28. ^ For well-illustrated and concise overview see Masterpieces of American Glass, text by Jane Shadel Spilman and Susanne K. Franz [exh. cat. The Corning Museum of Glass] (New York, 1990).

29. ^ Didron 1889-1890, pp. 145-46, also published separately, Ibid., pp. 36-37.

30. ^ See essay "Louis C. Tiffany's Coloured Glass Work," published in Kunst und Kunsthandwerk, 1 (1898): 102-11, trans. for the introduction for the 1899 Grafton exhibition, in Artistic America, Tiffany Glass and Art Nouveau, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1970), 193-212.

31. ^ McKean 1980, pp. 63, 67, 83, figs. 58-63; Duncan 1980, pp. 129-30.

32. ^ Francis Roussel, "Le vitrail Art Nouveau en Lorraine," in Lorraine, pp. 89-104.

33. ^ Lorraine, pp. 381 and 393, Nos. 161 and 174.

34. ^ Jean-François Luneau, Felix Gaudin: Peintre-verrier et mosaïste (1851-1930). Clermont-Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise-Pascal, 2006, 209, 370, fig. p. 570; Chantal Bouchon, "Le carton destiné à la verrière de la Chambre de Commerce de Paris par E. Grasset." La Revue du Louvre et des Musées de France (April, 1986): 131-38. The watercolor sketch and the cartoon were given by Mme. Blum through the intermediary of the Société des Amis d'Orsay. See Catherine Lepdor, ed. Eugène Grasset 1845-1917: l’art et l’ornement[exh. cat. Musée cantonal des Beaux Arts, Lausanne] (Milan 2011).

35. ^ Jean Taralon in Vitrail français, p. 216, fig. 216.

36. ^ Lorraine, pp. 383-91, 405-408, Nos. 163, 165-57, 170, 171, 190.

37. ^ William Warmus, Emile Gallé: Dreams into Glass (exh. cat., The Corning Museum of Glass] (Corning, NY: 1984).

38. ^ Lorraine, p. 93; On Daum, see Noel Daum, Daum, maître-verriers (Lausanne, 1980).

39. ^ Jacques Gruber, Ebéniste et maître-verrier 1971-1936 [exh. cat. Musée Horta] (Brussels, 1990?), col. pl. p. 62; Lorraine, pp. 306-307, No. 107, color pl. p. 177. Gruber also designed furniture, amply illustrated in the Brussels catalogue.

40. ^ See, for example good illustrations of these kinds of commissions: Hancock County, Ohio, Courthouse: John A. Kissh, Jr. "A Bit of Americana: The Hancock County, Ohio, Courthouse," Stained Glass 78/4 (1983-84): 380-83; La Porte County, Indiana, Courthouse :[Norman Temme, Taking A Stand for Restoration: The La Porte County, Indiana, Courthouse," Stained Glass 78/4 (1983-84), 384-86; Baltimore Railroad Station (C. Jackson Grace, "Rambush Decorating Company," Stained Glass 83/3 (1988): 190 and cover); Appelate Division Supreme Court, New York City windows designed by Maitland Armstrong, (Sturm 1982, fig. 55); The Players' Club, New York, City, remodeled in 1888 by Stanford White, when the windows by the Tiffany Studios were probably installed (Sturm 1982, fig. 42, 43); Bartlett Memorial Gymnasium, University of Chicago, 1903 by Edward Peck Sperry (Frueh 1983, pp. 108-109); Public Library, Troy, New York, 1897 by Tiffany Studios (Duncan 1980, fig. 25).

41. ^ Their grandfather had established the firm in 1850, then called Hopps & Sons. Edith Hopps Powell, San Francisco's Heritage in Art Glass (Seattle, 1976); Beverly H. Markou, "Rescuing a Landmark: San Francisco's City of Paris Dome," Stained Glass 78/4 (1983): 344-49. I am grateful to Ian Berke and Kathryn Wilen Hobart for facilitating study of these sites.

42. ^ Suzanne Tise, "Les Grands Magasins" in L'Art de Vivre. Decorative Arts and Design in France 1789-1989, David R. McFadden and others [exh. cat. Cooper-Hewitt Museum] (New York, 1989), pp. 73-106.

43. ^ Kokomo Opalescent Glass Company, Kokomo, Indiana, was incorporated in 1888. See Diane Roberts, "Man and Machine, A Legacy of Excellence," Stained Glass 87/1 (1992): 18-23, explaining the production of opalescent glass.

44. ^ See also Cypress Lawn Cemetery, equally typical of the opalescent embellishment of funeral homes and cemetery chapels of this era. The domes are more highly colored. Intense concentrations of red and green, blue and gold dominate the series of domes and oblong skylights.

45. ^ A plan had been done by architects John Galen Howard, John Reed Jr., and Fred. H. Mewyer. Arthur Brown Jr. was the designer in the firm of Blakewell and Brown. See Richard Guy Wilson, "Precursor: Arthur Brown, Jr., California Classicist," Progressive Architecture 64 (Dec. 1983): 64-71.