SEBASTIAN RÂLE (1652-1724):

IN COMMEMORATION OF

THE 275TH ANNIVERSARY OF

HIS MARTYRDOM

(23 August 1999)

|

|

A native of Pontarlier, France, Sebastian Râle was baptized on 28 January 1652 and joined the Society of Jesus on 24 September 1675. He came to America on 13 October 1689 and, after spending some time with the native Americans in Illinois (1692-95) and at Becancour (1705-11) in Canada, he lived most of his life among the Abenakis for whom he has the distinction of having established the first school ever in what is now the State of Maine. His was a period when England and France were engaged in a struggle for the control of North America. In that struggle, which was a religious as well as a political conflict, Father Râle incurred the wrath of the English who placed a price on his head because he kept the native Americans loyal to the French, centered at Quebec, as they maintained a defensive perimeter of forts on the rivers between New England and New France. Determined to stand by his flock, the native Americans of the Kennebec River Valley, and to defend their rights while caring for their pastoral needs and nuturing their religious beliefs and practices, Râle was cut down at his mission in Norridgewock, Maine, on 23 August 1724, as he defended his Abenaki flock with his life. This caused the Protestants throughout the region to rejoice at the death of this most famous Jesuit in colonial New England. In the wake of his death there was a Father Râle's War for two years in which the native Americans lost their lands with the triumph of the English. That his memory has been esteemed by many people in every generation since his saintly martyrdom is an indication of his stature in history.

THE CAUSE

In regard to the cause of sainthood for Rev. Sebastian Râle [variations of the name are Racle, Rasle, Rasles, etc.], a Jesuit missionary for many years in what was the Diocese (now Archdiocese) of Quebec and what became the Diocese (now Archdiocese) of Boston, Massachusetts, and what is now the Diocese of Portland, Maine, the essential qualifying condition for any candidate is the existence of a genuine and widespread "fama sancitatis" ("reputation for sanctity") from the time of the person's death up to the present. Certainly, this condition can be presumed to have been met in the case of Father Râle (and the other martyrs of what is now the United States) more than fifty years ago when Dennis Cardinal Dougherty of Philadelphia, as Dean of the American Hierarchy, first presented the cause of 116 United States Martyrs to the Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of Rites, under date of 23 September 1941, as documented in the work by Most Rev. John Mark Gannon (edited by Rt. Rev. Msgr. James M. Powers, LL. D., as The Martyrs of the United States, it was published in Easton, PA, 1957). Although that action of the American bishops in favor of Râle and 115 other martyrs was thwarted by the outbreak of World War II, Pope Pius XII, in a personal interview after the war (see the same work, pp. 192-194), told Archbishop Gannon, in regard to cause of the American martyrs: "This Cause is Beatutiful . . . most beautiful." What follows are eight points highlighting the available evidence about Father Râle's "fama sancitatis" from the time of his death down to the present.

First, from the Jesuit Relations (vol. 67, pp. 85 ff., 133 ff., and 231 ff., namely, the letter of Father Râle to his nephew on 15 October 1722, and the one to his brother on 12 October 1723, in additon to a third document of 29 October 1724 by Pierre-Joseph de La Chasse, Superior General of the Missions of New France), it is clear that the martyred Jesuit, the Apostle to the Abenakis, has been held in high esteem for his personal sanctity not only since the time of his death but even before his martyrdom on 23 August 1724 (Father de La Chasse, pp. 231-232, refers to this as "a glorious death, which was ever the object of his desire, --- for we know that long ago he aspired to the happiness of sacrificing his life for his flock"). Clearly, the letter of Father de La Chasse is proof that the Jesuit Superior of the Missions bear witness to a "fama sanctitatis" of Father Râle since the day of his death. That same letter, which is the oldest account of the martyr's death, tells how the Jesuit, in risking his life to save his flock, was shot dead at the foot of the large Cross that had been set up to mark the site of the mission village.

Second, regarding the years from Father Râle's death to the present, Father Antonio Dragon, S. J., in his work, Le Vrai Visage de Sébastien Râle (1975), has summarized (pp. 160-161) the evidence for and against the martyred Jesuit. Although Father Râle was hated by the English authorities in New England during his lifetime and regarded unfavorably by such authors as Samuel Penhallow (1726), Thomas Hutchinson (1767), John W. Hanson (1849), Francis Parkman (1867), James Phinney Baxter (1894), and Fanny Hardy Eckstorm (1934) because they shared either the anti-Catholic or anti-French viewpoint, any researcher can find an even stronger and more dominant opinion in favor of the priest from a number of non-Catholics, mostly of English background in New England, such as Jonathan Greenleaf (1821), Enoch Lincoln (1829), William D. Williamson (1832), Joseph Sewall (1833), Converse Francis (1845), William Allen (1849), George Bancroft (1883), John Francis Sprague (1906), Kenneth M. Morrison (1974), and Mary Calvert (1991). Among the Catholic writers favorable to Father Râle, in addition to Archbishop Gannon and Fathers de La Chasse and Antonio Dragon (not to mention the classical historians of the Archdiocese of Boston), one can point to Pierre-François Xavier de Charlevoix (1744), Bishop Benedict Joseph Fenwick, S. J. (1836), John Gilmary Shea (1857), Camille de Rochemonteix (1896), Edmund J. A. Young (1899), Henry C. Schuyler (1907), Thomas J. Campbell (1917), Mary Celeste Leger (1929), Martin P. Harney (1941), William Leo Lucey (1957), Thomas Charland (1969), Vincent A. Lapomarda (1977), James Hennesey (1981), Robert M. Chute (1982), and Albert J. Nevins (1987).

Third, over the years the increasing "fama sanctitatis" of Father Râle among both Catholics and non-Catholics can be demonstrated in other significant ways. The clearest manifestation of this is the annual commemoration of his martyrdom in which both Catholics and non-Catholics have been participating over the past generation, particularly in the geographical area of his saintly martyrdom. Father Dragon makes reference (p. 7) to such a celebration at Norridgewock, Maine, on the 250th anniversary of Father Râle's death and, in recent years, there has been an announcement annually in The Church World, the newspaper of the Diocese of Portland, Maine, for a similar celebration in which Catholics joined with their non-Catholic brethren in the area of Madison.

Fourth, while those celebration testify to the "fama sanctitatis" of Father Râle regardless of religious divisions among Christians, there have been other developments in the history of New England (especially since the martyrdom of the Jesuit) that emphasize how highly he has been revered among Catholics in New England. These are: (1) the marking of the site of Father Râle's grave by the native Americans themselves from the time of his martyrdom in 1724; (2) the recognition of his grave by the soldiers in Benedict Arnold's army when they were on their way to Quebec in 1775; (3) the erection in 1833 of an imposing granite monument over the grave of Father Râle by Bishop Fenwick, Second Bishop of Boston; (4) the establishment in Madison, Maine, in 1907, of a parish named in honor of the patron saint of Father Râle; (5) the historical memorial placed in 1924, by Bishop Louis Sebastian Walsh of Portland, in the Church of St. Benigne in Pontarlier, France, where Râle had been baptized; (6) the reaffirmation of Father Râle's contribution to the Diocese of Portland with the return of the Jesuits to Maine in 1942 to staff Cheverus High School; (7) the minting of a medal of Father Râle, designed by Allison Macomber, for Boston College's honoring of a number of good citizens, in conjunction with the American Bicentennial in 1976; and (8) the proclamation, as national Catholic historical sites, by the International Order of Alhambra, on 23 August 1999, of Father Râle's grave and the church named for his patron saint. Certainly, these eight milestones (not to mention units of the Knights of Columbus like the Fourth Degree Assembly, No. 337, in Portland dating from 1948 and of the circle of the Daughters of Isabella named in honor of the Jesuit) bear testimony to the "fama sanctitatis" of the Jesuit in the consciousness of New England where today not only the secular map of the State of Maine lists his monument as a historical site at Norridgewock, the place of his martyrdom, but where prominent institutions of higher learning such as Bowdoin College and Harvard University (not to mention the Maine Historical Society) have been engaged in preserving such memorabilia as the historic bell of his mission and his scholarly dictionary of the Indian language, in addition to some original letters of the Jesuit missionary, and the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a marking, on December 16, 2000, commemorating the site of the First Native American School founded by the Jesuit in what is now the State of Maine.

Fifth, if any weakness ever existed in the documentation available on Father Râle, it was underscored years ago by Arthur J. Riley when he emphasized (1936) how difficult was the problem of reconciling the account of Father Râle's martyrdom as given by de La Chasse sixty-seven days after the death of the Jesuit compared to the one that is given by Thomas Hutchinson whose authority rests on the testimony of participants recorded about forty years after the martyrdom. The particular virtue of Father Dragon's account is that he does not shrink from that challenge and presents a very satisfactory solution to the problem, especially in quoting (pp. 169-170) the testimony of Father Râle's Protestant biographer, John Francis Sprague. Perhaps the worst argument that could be raised against the Jesuit is that he advocated force in the defense of his flock, but reason teaches that every person has a right to self-defense against an unjust aggressor.

Sixth, not foreign to Râle's defense is the statement by John Gilmary Shea that it was "not easy to form an opinion" about the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest. In his edition of The History of New France by Charlevoix, Shea argues (5, p. 280, n. 2) that the Indians were "unwise" to resist the English when they could have saved themselves and the Jesuit by moving to Canada, as the Jesuit Superior had once suggested. Yet, even though the tragedy at Norridgewock was, to use Shea's word "foreseeen," the historians of the Archdiocese of Boston (Robert H. Lord, John E. Sexton, and Edward T. Harrington) have handled such an objection very deftly in defense of Father Râle (1, pp,. 133-134). In any case, such a reservation does not offer sufficient reason for hesitating to form an opinion about Râle's heroism any more than it does to form an opinion about those Jesuits who, having anticipated death, were slaughtered in El Salvador on 16 November 1989.

Seven, in the evaluation of any true martyr, theolgians find that three conditions, set forth by the scholarly Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini (1675-1758), the future Pope Benedict XIV (1740-1758), in his classic study of the 1730s, De servorum Dei beatificatione et beatorum canonizatione, are required: (1) a person must have risked life to the point of death; (2) this death must have been inflicted in hated of the victim's religion; and (3) this same death must have been volutarily embraced by the victim in defense of one's religious beliefs and practices. In the case of Sebastian Râle, there is no doubt within the Catholic community (and even outside of it), from the time of his death up to the present that all conditions have been fulfilled by his martyrdom. As Father Dragon has pointed out, Râle was not included among the Jesuit Martyrs of North America beatified in 1925 and canonized in 1930 because that group was restricted to the martyrs of the seventeenth century.

Eight, as far as the curative powers of Father Râle are concerned, one can point to the Old Point Indian Spring located not far from the memorial erected by Bishop Fenwick in memory of the Jesuit missionary. The effectiveness of the waters of this spring (". . . on the east bank of the Kennebec a short distance from the monument . . .") have been recognized by the native Americans and pointed out by Israel T. Dana as far back as 25 October 1882. For further information, one should consult (pp. 13-14) the compilation by Emma Folsom Clark and others, History of Madison (1962).And, it should be noted that the Church of St. Sebastian in Madison, Maine, conducts a monthly healing service with the expectation that the intercession of the Jesuit will become more manifest among the People of God.

Therefore, given the cumulative testimony presented here, the historical evidence shows that Rev. Sebastian Râle, S. J., in the words of leading church historians (Lord, et alii, vol. 1, p. 115, n. 69) was "a man of exalted piety and sanctity," and that there has existed a genuine and widespread "fama sanctitatis" regarding this Jesuit from the time of his saintly death down to the present. That interest in his beatification and canonization has perdured in the diocese of his martyrdom only confirms the strength of his cause within the Catholic community itself just as the recognition of his stature by writers outside of it (there was an article by Dwayne Rioux, "Father Sebastian Râle," in the Central Maine Morning Sentinel, for Nov. 30 and Dec. 1, 1991, and another by Sharon Mack, "Madison Marks Martyrdom of Father Rale," in the Bangor Daily News, August 21, 1992) continues to make readers within the State of Maine conscious of their rich heritage. While conditions required for advancing the cause of anyone are quite stringent, they are quite flexible with respect to a martyr, as evident from the study (chapter 4) by Kenneth L. Woodward, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn't, and Why (1990), a point that was not foreign to the causes of the 108 victims of the Nazis who were beatified in Warsaw by Pope John Paul II on Sunday, June 13, 1999. In this connection, it may be helpful to recall the response of the Superior of St. Sulpice in Montreal, Canada, when Father de La Chasse asked for the customary prayers for the martyred Jesuit missionary. Recalling St. Augustine, he declared "Injuriam facit martyri qui orat pro eo."And, Zenit News Agency, asserted this principle when, in a dateline from Vatican City, on 28 June 1999, it declared: "For recognized martyrs, no proof of a miracle wrought by their intercession is necessary before beatification." If that is true, then the beatification of this Jesuit is long overdue.

______________________________________________________________________________

|

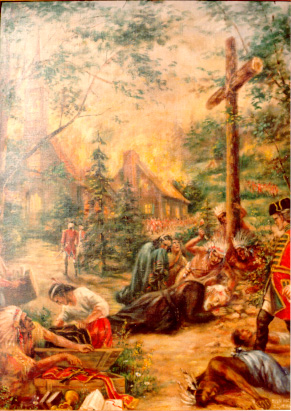

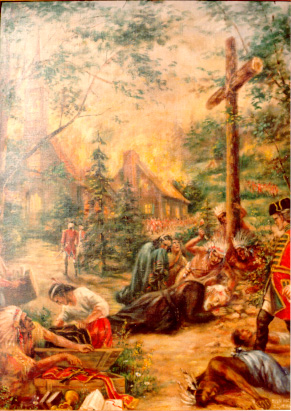

The above painting of the martyrdom of Sebastian Râle was done in 1941 by Mother Margaret Mary Nealis, R.S.C.J. (1876-1957). It used to hang in the Jesuit Residence of Cheverus High School in Portland, Maine, but now can be found in the Jesuit Residence of St. Pius X Church in that same city. The same nun did a number of other religious works, including the one for the canonization of the the Jesuit Martyrs of North America. Depicted among the hostile native Americans during the attack on the mission village are the Mohawks who were allies of the English. Though some of the chieftains among the braves at Norridgewock encircled the Jesuit to protect him as he faced his enemies, they were all killed (among them, Carrabassett, Job, and Wissememet, in addition to Bomazeen's son-in-law, according to J. W. Hanson) and the priest's body was atrociously mutilated almost beyond recognition. Among the thirty or so killed were also women and children. This painting is not the only portrayal of the martyrdom at a site that is marked today by a granite memorial. And, Sebastian Râle is one of three Jesuits memorialized in the glass windows of the Church of Notre Dame de Lourdes in Skowhegan, Maine.

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

Allen, William, The History of Norridgewock (Norridgewock, 1849)

Bancroft, George, History of the United States (6 vols.; New York, 1883)

Baxter, James Phinney, The Pioneers of New France in New England, with Contemporary Letters and Documents (Albany, NY, 1894)[p. 266: "In conclusion, Rale cannot be properly denominated a martyr, nor the English murderers . . ."]

Calvert, Mary, Black Robe on the Kennebec (Monmouth, ME, 1991)

Campbell, Thomas J., Various Discourses (New York, 1917)

Charland, Thomas, "Rale, Sebastien," Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Toronto, 1969), 2: 542-545

Charlevoix, Pierre François Xavier de, History

and General Description of New

France (6 vols. ed.from the French edition of

1744 by John

Gilmary Shea; New York, 1866-72)

Chute, Robert, Thirteen Moons/ Trente Lunes (Penumbra, 1982)

Clark, Emma Folsom, History of Madison (s. n., 1962)

Clark, William A., "The Church at Narantsouak," The Catholic Historical Review, 92: No. 1 (July, 2006), 225-251

Connolly, Arthur T., Fr. Sebastian Rale (New England Catholic Historical Society, 1906)

Convers, Francis, "Life of Rev. Sebastian Rale,"

Library

of American

Biography (2nd series; Boston, 1845), 8

Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

Dragon, Antonio, Le Vrai Visage de Sébastien Rale (Montreal, 1975)

Eckstrom, Fanny H., "The Attack on Norridgewock in 1724," The New Quarterly, 7 (September 1934), 541-578

Fenwick, Benedict Joseph, Memoirs to Serve for the Future (ed. by J. M. McCarthy; New York, 1978)

Gannon, John Mark, The Martyrs of the United States

(ed. by James M.

Powers, Easton, PA, 1957)

Greenleaf, Jonathan, Sketches of the Ecclesiastical

History of the State

of Maine (Portsmouth, NH, 1821)

Hanson, John W., History of the Old Towns of Norridgewock and Canaan(Boston, 1849)

Harney, Martin P., The Jesuits in History (New York, 1941)

Hennesey, James, American Catholics (New York, 1981)

Hutchinson, Thomas, The History of the Province of

Massachusetts-Bay

(Boston, 1767)

Lapomarda, Vincent A., The Jesuit Heritage in New England (Worcester, 1977)

---------- "The Jesuit Missions of Colonial New England," Essex Institute Historical Collections, 126: No. 2 (April 1990), 91-109

Leger, Mary Celeste, The Catholic Indian Missions of Maine (1611-1820)Washington, 1929)

L'Heureux, Juliana, The Franco-American Connection (Web Site, 2002)

Lincoln, Enoch, "Some Account of the Ancient Missions

of Maine,"

Collections of the Maine Historical

Society (Series 1; Portland,

1865), 1: 428-446

Lord, Robert H., Sexton, John E., and Harrington, Edward T., History of the Archdiocese of Boston (3 vol.; New York, 1944)

Lucey, William L., The Catholic Church in Maine

(Francestown, NH,

1957)

Morrison, Kenneth M., "Sebastien Racle and Norridgewock, 1724," Maine Historical Society Quarterly, 14 (Fall 1974), 76-97

---------- The Solidarity of Kin (Albany, 2002)

Nevins, Albert J., American Martyrs (Huntington, IN, 1987)

Parkman, Francis, A Half-Century of Conflict (Boston, 1867)

Penhallow, Samuel, The History of the Wars of New England with the Eastern Indians (Boston, 1726)

Powers, James M. (editor), The Martyrs of the United States of America (Easton, PA, 1957)

Riley, Arthur J., Catholicism in New England to 1788 (Washington, 1936)

Rochemonteix, Camille de, Les Jésuites et la Nouvelle France (3 vols.; Paris, 1895)

Schuyler, Henry C, "Rale (Rasle), Sebastian," Catholic

Encyclopedia

(1907), 12: 635-636

Sewal, Joseph, "Paper Read Before the Lyseum (1833),"

Maine

Historical

Society, 5: 8 (Portland, 1947)

Sprague, John Francis, Sebastian Râle (Boston, 1906)

Thwaites, Reuben (editor), The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents (73 vols.; Cleveland, 1896)

Williamson, William D., The History of the State of

Maine (2 vols.;

Hallowell, 1832)

Young, Edmund J. A., "The Diocese of Portland," in William

Bryne's and others, The History of the Catholic

Church in the New England

States (2 vols.; Boston, 1899), 2: 465-561

NOTE: For a site dealing with relics in general, see "For

All the Saints" at

http://www.forallthesaints.info/list.htm. For

historical relics of the property of Father

Sebastian Râle, one can consult the Maine Historical

Society and the Houghton Library

at Harvard University.

__________________________________________________________________

*******

Monument Erected by Second Bishop of Boston in 1833

(St. Sebastian Cemetery, Norridgewock, ME)

*******

Memorial Erected by Margaret Coffe Moore Chapter, D. A. Ar. in 1926

(Side of Road Outside of St. Sebastian Cemetry, Madison, ME)

SITE OF NORRIDGEWOCK INDIAN VILLAGE DESTROYED BY THE ENGLISH IN 1724.

OLD POINT MONUMENT BEYOND COMMEMORATES THE DEATH OF

FATHER RASLES AND INDIANS IN MASSACRE.

*******

Plaque Erected by International Order of Alhambra on 23 August 1999

(Vestibule of St. Sebastian Church, Madison, ME)

SEBASTIAN RÂLE (1652-1724)

A NATIVE OF PONTALIER, FRANCE, WHERE HE

WAS BAPTIZED ON 28 JANUARY 1652, SEBASTIAN RÂLE

WAS AN INCOMPARABLE MISSIONARY WHO CARED FOR

THE NATIVE AMERICANS OF THE KENNEBEC RIVER

VALLEY FOR MOST OF HIS PRIESTLY LIFE. RECOGNIZING

THE 23RD OF AUGUST 1999 AS THE 275TH ANNIVERSARY

OF THE SAINTLY MARTYRDOM OF THIS MOST FAMOUS

JESUIT OF COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND, WE HAVE DECLARED

THE SITE OF HIS GRAVE AND THIS CHURCH OF HIS PATRON'

SAINT NATIONAL CATHOLIC HISTORICAL SITES.

*******

Marker Dedicated by the Daughters of the American Revolution

on December 16, 2000, under Mrs. Claude C. Tukey, State Regent, 1998-2001:

(Inside St. Sebastian Cemetery, Norridgewock, ME)

FATHER RASLE'S SCHOOL AND MISSION

FOR NATIVE AMERICANS

ON THIS SITE, PRIOR TO 1705,

STOOD THE FIRST NATIVE AMERICAN

SCHOOL IN THE REGION NOW KNOWN

AS THE STATE OF MAINE.

THIS SCHOOL WAS ESTABLISHED BY

FATHER SEBASTIAN RASLE, A MISSIONARY,

PRIEST, AND TEACHER IN THE KENNEBEC

RIVER AREA FOR THIRTY YEARS.

FATHER RASLE'S ACTIVITIES INCLUDED THE

PREPARTION OF AN ABENAKI DICTINARY.

*******

_________________________________________________________________

The details of the life of Sebastian Râle can be summarized very briefly. A native of Pontarlier, France, he was baptized on 28 January 1652 and joined the Society of Jesus on 24 September 1675. He came to America on 13 October 1689 and, after spending some time with the native Americans in Illinois (1692-95) and at Becancour (1705-11) in Canada, he lived most of his life among the Abenakis of what is now the State of Maine. This was a period when England and France were engaged in a struggle for the control of North America. In that struggle, which was a religious as well as a political conflict, Father Râle incurred the wrath of the English who placed a price on his head because he kept the native Americans loyal to the French centered in Quebec, as they maintained a defensive perimeter of forts on the rivers between New England and New France. Determined to stand by his flock, the native Americans of the Kennebec River Valley, and to defend their rights while caring for their pastoral needs and nurturing their religious beliefs and practices, Râle was cut down at his mission in Norridgewock, Maine, on 23 August 1724, as he defended his Abenaki flock with his life. This caused his enemies throughout the region to rejoice at the death of this most famous Jesuit in colonial New England.

Over the 275 years since his

death, Father Râle’s memory has been

esteemed by many people in every generation. In itself, this

is a remarkable indication of his stature in the history of American Catholicism.

While he was not included in the list of the Jesuit Martyrs of North America

raised to the altar earlier in this century because they had been restricted

to the martyrs of the seventeenth century, he was on the list of 116 American

martyrs which the American bishops submitted to Rome on 23 September 1941.

Although World War II thwarted the development of their cause, Pope Pius

XII himself praised it as a worthy one. Today, given the reputation

for holiness of Sebastian Râle during his own life as well as throughout

the many years since his martyrdom, we know that his cause for beatification

is alive and well.

In the evaluation of any true martyr, theologians find that three conditions are required: (1) a person must have risked his life to the point of death; (2) this death must have been inflicted in hatred of the victim’s religion; and (3) this same death must have been voluntarily embraced by the victim in defense of one’s religious beliefs and practices. In the case of Sebastian Râle, there is no doubt within the Catholic community (and even outside of it), from the time of his death up to the present that all three conditions have been fulfilled by his martyrdom.

"Given this anniversary of the martyred Jesuit, I would like to memorialize it by reading excerpts from The Jesuit Relations (vol. 67, pp. 231-147) of the letter written by Pierre Joseph de La Chasse, Superior of the Jesuit Missions of New France, on 29 October 1724, sixty-seven days after Father Râle’s saintly martyrdom. It is the earliest account that we have of his martyrdom. In the words of his latest biographer, Mary R. Calvert: "This letter is the only eulogy we have of Sebastian Rale, and is a moving tribute to his years of unselfish devotion to his Abenaki flock.

"In the deep grief that we are experiencing from the loss of one of our oldest missionaries, it is a grateful consolation to us that he should have been the victim of his own love, and of his zeal to maintain the faith in the hearts of his neophytes . . .

"Father Rasles, the missionary of the Abenakis, had become very odious to the English. As they were convinced that his endeavors to confirm the native Americans in the faith constituted the greatest obstacle to their plan of usurping the territory of the native Americans, they put a price on his head; and more than once they had attempted to abduct him, or to take his life. At last they have succeeded in gratifying their passion of hatred, and in ridding themselves of the apostolic man; but, at the same time, they have procured for him a glorious death, which was ever the object of his desire, --- for we know that long ago he aspired to the happiness of sacrificing his life for his flock.

"After many acts of hostility had been committed on both sides by the two nations, a little army of Englishmen and their native American allies, numbering eleven hundred men, unexpectedly came to attack the village of Norridgewock. . . . At that time there were only fifty warriors in the village. At the first noose of the muskets, they tumultuously seized their weapons, ad went out of their cabins to oppose the enemy. Their design was not rashly to meet the onset of so many combatants, but to further the flight of the women and the children, and give them time to gain the other side of the river, which was not yet occupied by the English.

"Father Rasles, warned by the clamor and the tumult of the danger which was menacing his neophytes, promptly left his house and fearlessly appeared before the enemy. He expected by his presence either to stop their first efforts, or, at least, to draw their attention to himself alone, and at the expense of his life to procure the safety of his flock.

"As soon as they perceived the

missionary, a general shout was raised which was followed by a storm of

musket-shots that was poured upon him.

He dropped dead at the foot of a large cross that he had erected

in the midst of the village, in order to announce the public profession

that was made therein of adoring a crucified God. Seven native Americans,

who were around him and exposing their lives to guard that of their father,

were killed by his side.

"The death of the shepherd dismayed the flock; the native Americans took to flight and crossed the river, part of them by fording, and part by swimming. They were exposed to all the fury of their enemies, until the moment when they retreated into the woods which are on the other side of the river. There they were gathered, to the number of a hundred and fifty. From more than two thousand gunshots that had been fired at them only thirty persons were killed, including the women and children; and fourteen were wounded. The English did not attempt to pursue the fugitives; they were content with pillaging and burning the village; they set fire to the church, after a base profanation of the sacred vessels and of the adorable Body of Jesus Christ.

"The precipitate retreat of the enemy permitted the return of the Norridgewocks to the village. The very next day they visited the wreck of their cabins, while the women, on their part, sought for roots and plants suitable for treating the wounded. Their first care was to weep over the body of their holy missionary; they found it pierced by hundreds of bullets, the scalp torn off, the skull broken by blows from a hatchet, the mouth and the eyes filled with mud, the bones of the legs broken, and all the members mutilated. This sort of inhumanity, practiced on a body deprived of feeling and of life, can scarcely be attributed to any one but to the savage allies of the English.

"After the devout Christians of Norridgewock had washed and kissed many times the honored remains of their father, they buried him in the very place where, the night before, he had celebrated the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, --- that is, in the place where the altar had stood before the burning of the church.

"By such a precious death did the apostolic man finish, on the 23rd of August in this year, a course of thirty-seven years spent in the arduous labors of this mission. He was in the sixty-seventh year of his life . . . .

"Father Rasles joined to the talents which make an excellent missionary, the virtues which the evangelical ministry demands . . . We were surprised as his facility and his perseverance in learning the different tongues of the native Americans; there was not one upon this continent of which he had not some smattering. . . . From the time of his arrival in Canada his character had ever been consistent; he was always firm and resolute, severe with himself, but tender and compassionate toward others . . . .

"Three years ago, by order of Monsieur our Gouvernor, I made a tour of Acadia. I conversing with Father Rasles, I represented to him that in case war should be declared against the native Americans, he would run a risk of his life; that, as his village was only fifteen leagues from the English forts, he would be exposed to their first forays; that his preservation was necessary to his flock; and that he must take measures for the safety of his life. My measures are taken, he replied in a firm voice: God has confided to me this flock, and I shall follow its fate, only too happy to be sacrificed for it. He often repeated the same thing to his neophytes, that he might strengthen their constancy in the faith. We have realized but too well, they themselves said to me, that that dear Father spoke to us out of the abundance of his heart; we saw him face death with a tranquil and serene countenance, and expose himself unassisted to the fury of the enemy, --- hindering their first attempts, so that we might have time to escape from the danger and preserve our lives.

"As a price had been set on his head, and various attempts had been made to abduct him, the native Americans last spring proposed to take him farther into the interior, toward Quebec, where he would be secure from the dangers with which his life was menaced. What idea, then have you of me? He replied with an air of indignation, do you take me for a base deserter? Alas! What would become of your faith if I should abandon you? Your salvation is dearer to me than my life.

"He was indefatigable in the exercises of his devotion . . . Some native American families, who have very recently come from Orange, told me with tears in their eyes that they were indebted to him for their conversion to Christianity; and that the instructions which he had given them when they received Baptism from him, about thirty years ago, could not be effaced from their minds, --- his words were so efficacious, and left so deep traces in the hearts of those who heard him. . . .

"Notwithstanding the continual occupations of his ministry, he never omitted the sacred exercises which are observed in our houses. He rose and made his prayer at the prescribed hour. He never neglected the eight days of annual retreat; he enjoined upon himself to make it in the first days of Lent, which is the time when the Savior entered the desert. If a person does not fix a time in the year for these sacred exercises, said he to me one day, occupations succeed each other, and, after many delays, he runs the risk of not finding leisure to perform them.

"Religious poverty appeared in his whole person, in his furniture, in his living, in his garments. In a spirit of mortification he forbade himself the use of wine, even when he was among Frenchmen; his ordinary food was porridge made of Indian cornmeal. . . . Care was taken to send him from Quebec the necessary provisions for his subsistence. I am ashamed, he wrote to me, of the care that you make of me; a missionary born to suffer ought not to be so well treated.

"He did not permit any one to lend him a helping hand in his most ordinary needs; he always waited upon himself. He cultivated his own garden, he made ready his own firewood, his cabin, and his sagamité; he mended his torn garment, seeking in a spirit of poverty to make them last as long a time as possible. The cassock which he had on when he was killed seemed so worn out and in such poor condition to those who had seized it, that they did not deign to take it for their own use as they had at first designed. They threw it again upon his body, and it was sent to us at Quebec.

"In the same degree that he treated himself harshly, was he compassionate and charitable toward others. He had nothing of his own, and all that he received he immediately distributed to his poor neophytes. Consequently, the greater part of them showed at his death signs of deeper grief than if they had lost their nearest relatives. . . .

". . . his virtues, of which New France has been for so many years witness, had won for him the respect and affection of Frenchmen and native Americans.

"He is, in consequence, universally regretted. No one doubts that he was sacrificed through hatred to his ministry and to his zeal in establishing the true faith in the hearts of the native Americans. This is the opinion of . . . de Bellemont, Superior of the Seminary of Saint Sulpice at Montreal. When I asked from him the customary suffrages for the deceased , because of our interchange of prayers, he replied to me, using the well-known words of Saint Augustine, that it was doing injustice to a Martyr to pray for him, --- Injuriam facit Martyri qui orat pro eo.

"May it please the Lord that his blood, shed for such a righteous cause, may fertilize these unbelieving lands which have been so often watered with the blood of the Gospel workers who have preceded us; that it may render them fruitful in devout Christians, and that the zeal of apostolic men yet to come may be stimulated to gather the abundant harvest that is being presented to them by so many peoples still buried in the shadow of death!"

"So much for the eulogy of Father La Chasse’s letter. While those words were from one who was the Jesuit Superior of the region 275 years ago, I am happy to extend to everyone here present the greetings of Rev. Robert J. Levens, S. J., the Jesuit Superior of New England today. In a letter to the Jesuits of New England, under date of 17 August 1999, Father Levens said: "Last June, I wrote to Bishop Joseph Gerry, of the Diocese of Portland. As the local bishop, he would have a role to play in any process that might lead to the beatification and canonization of Father Rasle. In my letter, I inquired of Bishop Joseph whether he believes that there are sufficient signs of devotion in Main to warrant the Diocese to pursue the cause of Father Rasle. While I have not yet received a response from him, I will continue to pursue the matter prudently."

In light of the words of the current Jesuit Provincial of New England, I would like to conclude this homily by having us all together join in reciting the prayer which I have composed for the beatification of Sebastian Râle. You can find it on the reverse side of the card depicting the painting of his martyrdom by Mother Margaret Mary Nealis, R. S. C. J. This card has been made available through the kindness of Father Jon C. Martin who will bless the plaque that we are dedicating today.

"Eternal Father,

grant that Sebastian Râle, martyr of the faith among the Abenakis

of Maine, will be raised to the altar of the blessed. Through his

intercession, we pray that your divine favor will be manifest among us

so that we may return praise to your glory. We ask this through

through Our Lord Jesus Christ Your Son Who lives and reigns with you and

the Holy Spirit One God world without end. Amen."

___________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________________

In the opinion of historians,

it is generally recognized that the first school established in the State

of Maine was the mission school for native Americans set up by Rev. Sebastian

Râle, S. J., on the Kennebec River. This is evident from essays

on the web by Comptons

Encyclopedia and by the Discovery

Channel School. In this connection, the evidence for that

view is a document such as the following from The Boston News-Letter

for Monday, March 5th to Monday, March 12th of 1704-05 [Old Style] in which

this report from Colonel Winthrop Hilton is sent from Piscataqua during

the winter of 1705:

"Our Forces under the

Command of Lieut. Col. Hilton & Major Walton returned last night from

Narigwalk the Head Quarters of the Eastern Indians, who advise of a large

Fort, Meeting-house & School-house that were there erected, the Fort

encompassed 3 quarters of an acre of ground built with Pallisades, wherein

were 12 Wigwams but no Enemy; neither the discovery of any Tracks seen,

but of 3 or 4 supposed to be there about 3 weeks since, no plunder excepting

a few Houshold Utensils of little value; The Meeting-house was built of

Timber 60 Foot long, 25 Foot wide, & 18 Foot studd ceiled with Clapboards,

in it were only a few old Popish Relicks; the School-house lay at one end

distinct, all which they burnt, near to it was a Field of Corn ungathered,

which may be imputed to he Enemy’s desertion by the consternation that

seized them at the Ransacking of the Eastern French & Indians Settlements

the last Summer. . . "

In addition to

that testimony, there is the evidence from history of the traditional way

that the Jesuits went about establishing their missions, that is, by making

education a key to the same. From the letters (see Jesuit Relations,

vol. 67, pp. 96 ff., the letter of October 15, 1722) of Father Râle

himself, this is clear, for example, in the controversy that the

Jesuit had with Rev. Joseph Baxter. Based on such evidence, the historians

for the History of the Archdiocese of Boston (1944), state (vol.

1, p. 97): "At various times there was school, too." And, Mary

R. Calvert, in her study, Black Robe on the Kennebec (1991), specifically

mentions how the Jesuit missionary educated Dorothee Jeryan and Esther

Wheelwright who were taken as captives by the native Americans.

In conclusion,

it enlightening to recall the words of the William D. Williamson, whose

classic work, The History of the State of Maine (1832) did not hesitate

to acknowledge the contribution of the Jesuit missionary. Thus, in

writing about the Jesuit's work in the education of the native Americans,

he speaks of Râle as "their tutelar father" while not failing

to note that for ". . . many of them he had

taught to read and write . . . " (vol. 2,

p. 102).

___________________________________________________________________________