|

|

|

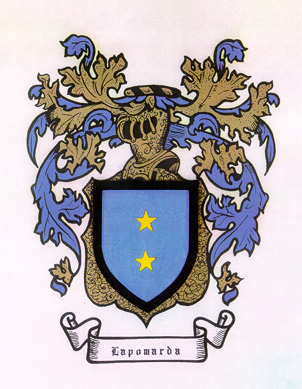

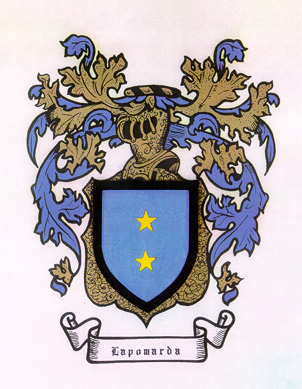

THE LAPOMARDA COAT OF ARMS

In exploring the derivation and meaning of the family name Lapomarda, history

cannot be neglected. Given the long history of

Italy, it was really, as one statesman declared, "a geographical

expression" for a group of independent states before its unification in

the second half of the nineteenth century. At various stages, especially

in its modern history, the country was very much under the rule of both

the French and Spanish. Given such a background, the roots of one's

family name could have easily evolved from the Latin through the

French and the Spanish, in addition to the Italian

origins of the name, given the relationship of these Romance languages.

Since armies were known to cross Europe and travel into the Middle East

during the Crusades, it is not unlikely that the name Lapomarda evolved

in the period from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries before it became

recognized as a surname by 1490. By this time, one of the Crusaders

from Spain (or any other region) could have very easily settled on the

Adriatic coast of Italy (at Vieste,

for example, one finds the origins

of the Lapomarda name), in what is Apulia

(Puglia).

From this area, travelers could easily move to the Holy Land or even back

to Spain, at a time when coats of arms were not unknown in Europe. That

the region

is marked by a Norman cathedral

dating from the eleventh century and with historic castles,

especially the thirteenth century one of the Emperor

Frederick II, indicates Vieste's

links with the past and the Crusades. Recently, Terry Stanfill has

written a novel, The

Blood Remembers (2001), anchoring Vieste

with this past.

If one can date the Crusades as far back as 1096, history shows that various

coats

of arms were used to distinguish various persons and families.

In fact, Johannes de Bado Aureo, who published Tractatus de Armis

about 1394, held that arms were used to distinguish one person from another.

Eventually, according to Sir

William Dugdaleís The Ancient Usage of Bearings of Arms (1681),

arms were used to distinguish one family from another. Yet,

given the free adoption of coats of arms in the Middle Ages, one must be

cautious

about their use and meaning for anyone in this period of history in light

of Italy's rivarly between the Guelfs

and the Ghibellines.

Since nobles in the Crusades were the first to use surnames, these arose

from the lands they owned, some relationship, some nickname, some personal

characteristic, or some occupation that identified one person from another.

However, Italian heraldry,

not unlike the field of heraldry

in general, is not so easy to decipher if one investigates its

origins. Though there are various ways to investigate the

background

of one's family name, based on Giovanni B. Di Crollalanza's Dizionario

Storico Blasonico delle Famiglie Nobili e Notabili Italiane (3

volumes; 1886-90), the heraldic description of the Lapomarda coat of arms

is an azure field with two muellets of gold in a perpendicular position

on a shield edged in black. The muellets or stars symbolize the association

of the name with the civil authority.

In that way, then, the Lapomarda surname could very well have been the

family name of a gentleman, a baron, or a knight many years before

Italy was united. When the name was evolving from the eleventh

to the thirteenth centuries, this person could have been the owner of an

apple orchard if one considers the Italian word for apple (pomo)

and for apple orchard (pomario) which is not

unlike the Spanish word for the same (pomar). Recognized

as a surname by the end of the fifteenth century, Lapomarda could, in a

certain true sense, be the equivalent of Appleyard

in English given those words from the Romance languages. Yet, on

the other hand, when one considers the words for ointment in both

Italian (pomata) and Spanish (pomada), that conclusion

is open to question.

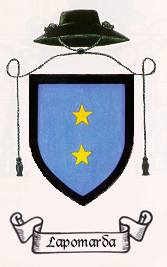

While the helmit signifies a gentleman, a baron, or a knight, the Lapomarda

coat of arms appears, more accurately, to depict that of a peer. However,

in making the Lapomarda coat of arms relevant for a priest, James-Charles

Noonan, Jr., in his study, The Church Visible: The Ceremonial Life and

Protocol of the Roman Catholic Church (Viking, 1996; pp. 525-526; Plate

61) states: "The arms of a priest are ensigned by a black galero with two

black fiocchi on the brim and one fiocchi suspended on either side of the

shield." Consequently, by extracting the shield from the knightly

insignia of the Lapomarda coat of arms, the coat of arms was

produced for Rev.

Vincent A. Lapomarda, S. J., a priest and a historian

who

is a member of the Angelo

Roncalli International Committee and is listed in Who's

Who in America for 2002 and a sponsor of Italian

genealogy.

From the consideration of the coat

of arms and its heraldic origins, one is led to the study of genealogy,

thereby indicating the link

between

the two. The surname Lapomarda originates in Vieste

(Foggia), Italy, where the father of Rev. Vincent A. Lapomarda, S.

J., was born. Back in the fall of 1975, the latter visited there

and was able to obtain information that traced the family back to at least

his great great grandfather. If the priest had remained there longer,

he would have been able to go further into the church (Chiesa di Santa

Croce -- Church of the Holy Cross) records (the records in the

town hall did not go as far back) and was told that documents were available

(in the diocesan archives at the sub-cathedral, there) that could

take one back to the sixteenth century.

Vieste

has an interesting

history.

It had an espiscopal see dating from the eleventh century and it was a

town that was sacked by the the Turks under Draguth in July of 1554.

Under Pope John Paul II, in 1986, the old diocese of Vieste

was united with Manfredonia, which dated from the third century, so that

the combined dioceses are now known as the Archdiocese

of Manfredonia-Vieste-San Giovanni Rotondo (in the case of Vieste,

the cathedral, which, according to legend, was built on the site of an

ancient pagan temple, was known as Santa

Maria Oreta). This was the archdiocese which successfully advocated

the cause of Padre

Pio (1887-1968), a Capuchin who lived within its jurisdiction and who

was canonized,

on June 16, 2002. And, it is famous for its annual celebration on

May 9th of the Feast of Santa Maria di Merino, the Patroness of the City

of Vieste, about which Marco Della Malva has written the definitive historical

study, La Citta e La Madonna di Merino (1970).

Pasquale Lapomarda, Sr. (1895-1967), father of Rev. Vincent A. Lapomarda,

S. J., came to the United States through the Port of Boston, on 2 February

1910, after his departure, with his older brother Lorenzo (1886-1973) on

19 January 1910, from Naples, Italy, on the Duca di Genova.

He was born in Vieste,

Italy, on 26 (sometimes given as 27 which may have been his baptismal

date) June 1895, the son of Vincenzo (1853-1899) and Concetta (Fasulo)

Lapomarda (1859-1941) who were married, on 29 May 1879. Since he

came directly to the United States from Italy, Pasquale's name has been

inscribed on the American Immigrant

Wall of Honor (Panel 244) on Ellis Island in New York. At

Cheverus

High School

in Portland, Maine, from which his sons and grandson have

graduated, a scholarship was established in his memory in 1989 and, in

2001, on the death of his wife, was extended to include her so that

it is now known as as the Pasquale, Sr., & Mary N. Lapomarda Scholarship.

Vincenzo's family was at least the fourth generation of Lapomardas who

had their roots in Vieste, in the

Province of Foggia, Italy, where the family belonged to Santa Croce

which

is the church located in that same town. Vincenzo, the son of

Francesco Paolo (1813-1876) and Maddalena Solitro (1819-1897) Lapomarda,

was born in Vieste, on 27 July 1853, and died, on 2 January 1899.

With his marriage to Concetta, a native of Bisceglie

in Italy (Province

of Bari), he became the father of three sons (Francesco, d. 1954;

Lorenzo, d. 1973; and Pasquale, d. 1967) and one daughter (Michelena, d.

1977). The parents of Francesco Paolo (he was born in Vieste on 16

January 1813), Vincenzo's father, were Michael Antonio and Pasqua

Quarti Lapomarda while those of Maddalena (she was born in Vieste on 16

August 1819 and a great great great grandaughter was born the same day

in Salem, Massachusetts, in 2001), Vincenzo's mother, were Michele Solitro

and Caterina Bua who bring the genealogical line into the eighteeenth century.

Keeping

in mind what was said above about the origins of the family name, Lapomarda,

the frequency of the use of Vincenzo itself even can be considered to underscore

or reflect a Spanish connection. This emerged in the study of the

derivation of the of the Lapomarda name itself. That the use of Vincenzo

(Vincent) may derive from Italy's connection with Spain where St.

Vincent of Saragossa is revered as the

first martyr of that country cannot be discounted. In fact,

this could account for the popularity of the name of Vincent in areas of

Europe, including Italy itself, which were under Spanish control as recently

as the nineteenth century. And, that Vincenzo is the

most popular of the names among the Lapomardas in Italy today would

help to reinforce those historic connections.

Vincenzo

had at least one brother, Michele Antonio, born on 26 January 1844, and

one sister, Pasqua (Pasquaruccia or Pasqualina), who married Antonio Innocente

(Innocenti) on 21 May 1885. Michele Antonio married Anna Maria Di

Lello, a girl from the area of Bari

and

settled in Ginosa or Lecce where they raised seven boys (Francesco Paolo

and Vincenzo were the names of two of them), all of whom had jobs as conductors

on the railroad where their father was employed. And, perhaps, this is

why today the phone book for the Bari area lists

more than twenty-five Lapomardas, even though the family name is still

present in Vieste which is noteworthy for Lorenzo

Fazzini (1787-1837), a priest and mathematician. In fact, the

Lapomarda name exists in some forty-eight

areas

of Italy today.

A survey of telephone books also indicates that Italy has at least one

hundred and fifty households with the name Lapomarda

among

them, not to mention at least two more households in Belgium and three

in Germany while Ancestry.com

confirms

that with one hundred and seventy-five in Italy and at least six

more households in France. All this is more than there are among

Italian

Americans in the United States, where in some cases the name became

Lapomardo

which is quite common in Worcester County in Massachusetts (in this connection,

one can find a map in The Boston Globe, Wednesday, October 12, 1960,

which includes the name Lapomardo [not found in Italy], instead of Lapomarda

[found in Italy], in a map for Italian families in Massachusetts) where

this same name traces its origins back to Vieste, Italy, and Lapomarda

before he last vowel of the family name was changed in the processing of

immigration to the United States. Such changes were not unlike those an

immigration official might make in writing an Italian name like "Casa"

as "Casey" into the records. For more on the

Viestani who came to the United States (and a good source for those

who migrated

from Italy at the end of the ninetenth century), see the multi-volume

work Italians

to America.

Until he became an American citizen on 1 October 1940, Pasquale Lapomarda,

Sr., remained an Italian citizen and his children automatically became

Italian citizens because of him. Since the Supreme Court of the United

States ruled a generation later that it was legal for United States citizens

to hold dual citizenship, children of Italian citizens enjoy Italian

citizenship until they voluntarily renounce it. In general, this

is still true of all those of Italian

heritage in the United States as one can determine more exactly from

the

guidelines set forth, especially if one is interested in obtaning an

Italian passport.

Today,

of course, in a multicultural dual citizenship is for many a badge of honor.

However, around the time Pasquale became an American citizen, it should

not be forgotten that Italian Americans, in addition to others,

were the victims

of discrimination in both the United States and in Italy because of

World War II. In the United States, to which

Italian Americans have contributed throughout

its history, they were

persecuted because they had migrated from a nation that was at war

with their adopted country, a story set forth in

Una Storia Segreta. And if any served as military persons and

were captured by any of the Axis powers, the enemy reportedly was not reluctant

to execute them as traitors to Italy.

Tracing one's family name back many generations might lead one to outstanding

historical figures like Charlemagne

and, perhaps, even to Caesar.

But, if one looks at the process closely, such an endeavor really ceases

to be meaningful after one has gone back to the fourth or fifth generation.

In the final analysis, everyone can trace back their ancestry in faith

to Abraham

or to Adam

and Eve, the first

man and the first woman in the Bible. While genealogy can prove to be fascinating

and satisfy some unknown psychological need in the human

quest for one's roots, there is a stage, objectively, at which the

search becomes somewhat meaningless, and even questionable, given the lack

of documents. As one moves deeper into the past where, before the

invention of the printing press, much tends to be enshrined in legend and

myth, there is really a lack of objective evidence, the fundamental criterion

of truth.

On his mother's side, Father Lapomarda is related to the Bartholomews.

Mary N. (Bartholomew), his mother, was born in Portland,

ME, on February 2, 1904, the daughter of Erasmo Bartholomew and

his wife, Giuseppina (1873-1932), and died in her native city on May 11,

2001. Born in Formia

(Lazio),

Italy, on 24 October 1869, Erasmo, Mary's father, came to this country,

arriving by ship in Providence, Rhode Island, on 26 September 1893, having

left his native town, in the Province

of Latina, located between Rome and Naples on the Gulf of Gaeta.

It was famous for two historic sites, the villa of Cicero,

the Roman orator and statesman, and the Church of St.

Erasmus, his own patron saint. In that church for generations, the

ancestors of Erasmo had been baptized so that as late as 1975 there existed

parish records in that parsish which could trace the family back to the

sixteenth century.

For

the next few years, Erasmo established himself in Portland working as a

bricklayer and a stonemason before he sent for his family. This included

his wife, his son, Samuel (1893-1969), and his parents (Tommaso and Teresa

Bartolomeo). When he became a citizen of the United States on 29 November

1905, Erasmo concentrated on construction while his daughter took

care of her father's business books. With the boom in construction during

that period of prosperity, the grocery store closed as Erasmo extended

his interests to real estate until the

Great Depression forced him back into the grocery business. Before

his retirement, he opened a tavern on Washingotn Avenue in Portland where

he sold beer at twenty-five cents a pitcher.

When he died

in Portland, on 20 March 1943, Erasmo had been among the city's Italian

Americans for a half century. As a communicant at St. Peter's Church,

he saw this church, located on Federal Street, develop into the original

center of Italian culture in Maine. Like many other immigrants, Erasmo's

decision to come to the United States required courage, faith, and vision.

His adjustment to American society was clearly evident in the English

version (Bartholomew,

for some Americans of this name there exists a coat

of arms) of his Italian name, originally Di

Bartolomeo which became

Bartolomeo for his father who settled in Portland, Maine, a state which

numbered in the census for 2000 about 60,000

Italian Americans who constitute slightly less than five percent of

the state'e population. With other immigrants, like the great grandfather

of George Washington and the great grandfather of John Fitzgerald Kennedy,

Erasmo Bartholomew too, like father and his son-in-law, is memorialized

on the American Immigrant Wall of

Honor (Panel 489) on Ellis Island in New York.

As for the publication of Father Vincent's books, they include The Jesuit

Heritage in New England (1977), The Knights of Columbus in Massachusets

(1982, 1992, and 2004), The Jesuits and the Third Reich (1989 and

2005), The Order of Alhambra (1994 and 2004), The Boston Mayor

Who Became Truman's Secretary of Labor (1995), Charles Nolcini

(1997), The Catholic Church in the Land of the Holy Cross (2003),

The

Jesuits in the United States (2004), A Bibliography of the Published

Writings of Vincent A. Lapomarda (2004), A Century of Judges

of Italian Descent in Massachusetts (2005), and A Half Century of

Mayors of Italian Descent in Massachusetts (2006).

_________________________________________________________________________