Click to Enlarge

The Adam style takes its name from two brothers, Robert and James Adam, professional architects who, in the latter half of the eighteenth century, ushered in and secured a place for Neo-Classical architecture in Britain. The two would eventually run one of the most successful architectural firms in England, designing homes for the wealthy aristocracy. It was, however, the ideology, the experiences, and genius of Robert Adam that truly influences and gives shape to the movement, or revolution, as it is sometimes described.

Robert Adam was born in 1728, the second son of William Adam, one of the most prominent architects in Scotland of his day. At the age of twenty-six he left Scotland for France, where he met the esteemed architect C.L. Clérisseau, and toured the country from Paris to Nîmes. The next year, 1755, he entered Italy and by 1756, he had made his way to Rome. He traveled as a gentleman, but his interests, were, no doubt, professional. In 1757, for example, he journeyed to Spalato to study the ruins of Diocletian’s palace, a subject on which he published the Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro[sic] in Dalmatia. By the time Adam had returned to England in 1758, he had already gained the experience which would help to make him one of England’s leading architects.

From his study abroad Adam learned a number of things about the architecture of antiquity. He concluded, through his first hand observation, that classical architecture was not nearly as rigid as had been presupposed. Students of Palladio, and, indirectly, Vitruvius, regarded the layout of a building similar to the result of a mathematical equation, constrained by laws and grounded in truth. Proportions were rigidly outlined in Palladian handbooks, and the classical architecture of his school of thought left no room for interpretation. All of this thinking was to change in the age of Adam. Perhaps the most significant contributions made during that period were the archaeological studies done at classical sites throughout the former Roman Empire. These studies came at a time when historians had defined a clear historic view of antiquity—the classical era as distinct from the Medieval and Renaissance periods. The previous belief saw one long tradition, stretching from the present day back to the ancients, with a brief deviation in the so called Dark Ages. The result of these archaeological findings and the subsequent affect it would have on architecture can be summed up in three points:

| Slide

Gallery:

Click to Enlarge |

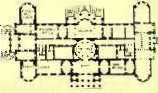

Luton Hoo (1766-1770), the Derby House (1773-1774), and the estate he designed

for his brother James Adam (circa. 1780) illustrate this new interior style.

The floorplan (Fig, 3) of Luton Hoo demonstrates the originality of the

use of interior space employed by Adam. The rigid symmetry of Palladio

and Inigo Jones is gone and in its place is a style which fits the space

to need. Notice the difference in the utilization of space in the wings

of the house--on one side there is great library which is the entire wing,

and opposite it, the wing is divided into five distinct units for separate

purposes. Also of note is the use of the curved line as a structural element,

as is evident through the oval rooms and bowed walls.

| Slide Gallery: Click to Enlarge |

Fig.3 Robert Adam; Luton Hoo floorplan |

| Slide

Gallery:

Click to Enlarge |

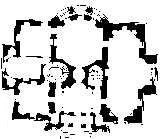

Fig.4 Robert Adam. Derby House, Floorplan |

Fig.5 Robert Adam. John Adam House, Floorplan |

|

|

|