![]() Melissa

Pelesz, '02

Melissa

Pelesz, '02

|

Educational Philosophy in the Lawn and Pavilions at The University of Virginia |

|

I. Preamble:

Melissa Pelesz, '02

Thomas Jefferson's

Educational Philosophy

in the

Lawn and Pavilions

at

The University of VirginiaI. Preamble:

With these words, Thomas Jefferson not only expressed his ideas

and dreams, but as he so often did throughout his life, he also embarked

on a quest to obtain his goals and make his dreams come true. As one of

the most well-educated, meticulous men of his times, an experienced politician

and lawyer, a passionate architect, and an Enlightened visionary, Thomas

Jefferson envisioned, developed, and accomplished his dream of establishing

an institution of higher learning that would educate the common individual,

unite students and professors in a common bond of learning, and model classical

architecture through his founding of the University

of Virginia.

II. Jefferson’s Life and Education:

Thomas Jefferson, the man that would one day change the course of this country’s public educational system, was born on April 13, 1743. He was born at Shadwell in Albermarle County, Virginia, to Peter Jefferson and Jane Randolph. Albermarle County, nestled in the backwoods of Virginia, provided the playground that Jefferson grew up in and instilled in him a love of nature that would last his entire life (Arrowood 4). Although Jefferson enjoyed his time amongst the trees, streams, and forests spread out amongst the land, he also began his formal studies at the early age of five. Peter Jefferson entered Thomas in an English, or elementary, school (Arrowood 5). After four years, at age nine and for the next five years, Thomas Jefferson stayed with the Reverend William Douglas, the first of several Scottish men to teach him. Douglas taught Thomas Jefferson Greek, Latin, and French. Although when Jefferson reflects on his education he comments that Douglas was "a superficial Latinist less instructed in Greek," he believed Douglas did a satisfactory job teaching him French (Randall 16).

However, as Jefferson broadened his mind and excelled in his studies, tragedy struck when his father died on August 17, 1757. At age 14, Thomas Jefferson acquired his father’s belongings and entered into a grievance period (Randall 18). Since Peter Jefferson’s dying wish was for Thomas Jefferson to continue on in his education, Thomas was sent to a classical academy, held in a log house and headed by the Reverend Mr. James Maury, who had attended William and Mary College and taught there for a short time (Randall 21f.). During Jefferson’s two years at the academy, Jefferson wrote about the hardship of losing his father and the frustrations he had when dealing with his mother (Randall 25). His writing allowed him to express his feelings and release some of the stress and frustration he was experiencing. Reverend Maury stressed to Jefferson, the student, the acquisition of the precise meaning of words, which allowed Jefferson to development his well-known, strong English prose. Thomas Jefferson attributes his introduction to natural philosophy to Reverend Maury, who instilled in him the foundation of a broad and growing classical education and the qualities of caution, self-discipline, and patience (Randall 22f.). Also during this time, Jefferson began to keep notes and extracts, including ones expressed during the grief for his father, in his Commonplace Book. He also kept records of his horse breeding in his Stud Book and records of his horses’ genealogy in his Farm Book. As Jefferson studied and learned about the world around him, practices such as his record keeping, love for reading, and a strict study schedule, exhibited his desire for structure and organization (Randall 29). His art for organization and his desire to master his classical studies marked his ambitious and tenacious personality.

Jefferson would continue his acquisition of a classical education while

learning how to participate in law and business at William and Mary College.

Just like all young gentlemen who were expected to seek a higher education

at William and Mary, Jefferson left for Williamsburg in March of 1760 (Randall

33). He continued his record keeping by noting his daily expenditures

as soon as he arrived (Randall 36). After beginning

classes on May 25, 1760, Jefferson entered into a period of study during

which he would perfect his Latin, English writing, public speaking and

mathematics (Randall 30, 37). However, he also embarked

on deep and concentrated studies as he searched for an understanding of

English law (Randall 37). Jefferson originally studied

under Reverend John Rowe until Rowe was dismissed after his involvement

in a drunken town brawl. Dr. William Small, obtained from Scotland as a

graduate from the Scottish College at Aberdeen, subsequently acquired all

of Rowe’s classes instead of the physics, metaphysics, and mathematics

he initially came to teach (Randall 37). As a result,

Dr. Small not only tutored Jefferson in mathematics, moral philosophy,

and science, but also became Jefferson’s surrogate father. It was Dr. Small

who became Jefferson’s role model and who instilled the Enlightened way

of thinking in Jefferson’s mind (Randall 38). Later

in his life, Thomas Jefferson gives credit for his architectural achievements

"to the good foundation laid at college by my master and friend Small"

(Randall 39).

III. Jefferson’s Early Political Career and Educational Philosophy:

Very early in his life, Jefferson made his education a priority and in doing so excelled to a point where he could influence and mentor others. While expressing his sheer admiration for education, he states that "if I had to decide between the pleasure derived from a classical education which my father gave me and the estate he left me, I would decide in favor of the former" (Culbreth 77). His love for education and advancement in it caused many, including James Madison, his nephew Peter Carr, Thomas Mann Randolph, and many more, to seek Jefferson’s advice as to the best course of study (Arrowood 17). During the time period between 1767 and 1776 when Jefferson entered Congress, he had a very successful law practice, continued working his farm, and became a leading Virginia patriot (Arrowood 8).

While at William and Mary College and studying and practicing as a young lawyer, Thomas Jefferson was surrounded by the buildings and culture of Williamsburg. While in town, Jefferson began to recognize social class distinctions (Randall 33). He also began to look more closely at architecture he had not noted carefully beforehand. William and Mary College was built in 1694 and supported by customs duties. Two main buildings, built with red-brick, comprised the campus. The President’s House, called the Wren Building is where Jefferson lived during his stay at school. The other building is called the Brafferton Building. The two buildings were connected by a walled garden (Randall 37). The buildings for the College were based on designs of Sir Christopher Wren, with the Wren building resembling the East Wing of Chelsea Hospital in London. (Illustration 5) Twenty-five years after his education, Jefferson remarked about the architecture of William and Mary by calling it "rude, misshapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick kilns" (Randall 35). Furthermore, other American colleges of the time, Harvard, Yale, and what would become Princeton also consisted of single, multipurpose buildings (Woods 267). With Jefferson’s exposure to architectural handbooks by Andrea Palladio and James Gibbs, he developed insight into the proper forms and most stunning examples of classical architecture. As a result, the only structure in Williamsburg, amidst the several wooden houses painted in white, that Jefferson remotely considered appropriate architecture was the new Capitol building, situated at the Western end of the town. He described the building as "light and airy" (Randall 35). His dissatisfaction with the architecture in Williamsburg and his education at William and Mary provoked Jefferson to search for improved architecture and methods of teaching that Jefferson would later offer back to many in his future educational establishments.

After developing a passion for architecture and acquiring the reputation of a well-read and very intelligent man, Thomas Jefferson developed his ideas about a better educational institution when Lord Dunmore sparked his interest. As Governor of the British Colony of Virginia, in 1771 or 1772, Dunmore asked Jefferson to design an addition to the main building at the College of William and Mary (Wilson 9). Before starting this architectural project, Jefferson first changed the academic setup of the college. William and Mary initially consisted of a preparatory grammar school, the Indian school for a handful of Native Americans, a divinity school to prepare individuals for the Anglican clergy, and the philosophy school (Randall, 37). Jefferson eliminated the grammar and divinity schools and further added a law school, headed by George Wythe, a school for medicine, anatomy, chemistry, and surgery, chaired by Mr. McLung, and finally he added a school for modern languages, headed by Mr. Bellini (Wilson 10).

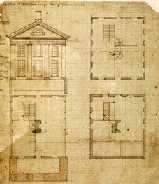

To improve the architectural arrangement of the college, Jefferson wanted to complete the college’s quadrangle, an English tradition. He consulted one of Andrea Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, as Jefferson would continually do in the future, from which he chose the palazzo form. Jefferson designed a quadrangle with an interior arcade and an open courtyard (Wilson 9). (Illustration) Although foundations were laid to begin the endeavor, the process was halted as Jefferson embarked on his role within the Revolution (Woods 273). However, these plans, put aside for the moment, would again resurface as the foundation for a monumental plan filled with superior architecture that reflected an educational ideal beyond its era.

After designing changes for the College of William and Mary, Thomas Jefferson continued his passion for education through his endless readings, which provided him with the ideas he used to develop an educational philosophy ahead of its time, but fundamental to this country’s survival as a democratic government. He read many authors, including Locke and Hume, Bolingbroke and Milton, all of whom were English writers. Although many may underestimate the English influence on Thomas Jefferson, he actually said, "Our laws, language, religion, politics and manners are so deeply laid in English foundation, that we shall never cease to consider their history as a part of ours, and to study ours in that as its origin" (Arrowood 57). For instance, Thomas Jefferson’s future idea for a proctor who would manage students’ money originated in England (Arrowood 52). Jefferson also had a broad spectrum of influential French reading, including Rolland, La Cholotais on his "Essai d’education nationale, Diderot’s "Plan of a University," and Turgot’s "Memoir of 1775" (Arrowood 57). As a result, some of Thomas Jefferson’s educational beliefs reflect those of French educational theory during the eighteenth century. One of his beliefs that mimicked the French was Thomas Jefferson’s view that students "should be freed from ecclesiastical control," the fact that he "advocated universal education," and that he wanted to base his educational doctrine in philosophy. However, Jefferson differed from the French because he did not believe education should be an instrument of nationalism and he also advocated for public support and control of education (Arrowood 49). Thomas Jefferson, a man willing to listen and learn, may have also been influenced by his many conversations with friends while in France (Arrowood 56).

In addition to Thomas Jefferson’s readings, many give credence to the

possibility that Jefferson’s development of his educational theories evolved

through his writing, similar to when he wrote the Declaration of Independence:

As Thomas Jefferson wrote, he strengthened his own beliefs about

how American education should be. His architectural visions and thoughts

on educational materials were founded on his beliefs not only for a more

improved method of educating, but on beliefs for a country full of pride

for the education and advancement of all its youth. Unlike the beliefs

of many of his contemporaries, Jefferson believed that a son should be

educated to rise above the station of his father (Wilson

10). Jefferson understood "that the emancipation of mankind from the

bonds of various servitudes centered in education" (Culbreth

78). Although many thought that a son purposely surpassing a father’s

stature could be considered disrespectful, Jefferson was humble enough

to realize that the constant improvement and advancement of each generation

not only would protect democracy for the future but also develop a stronger

and aspiring nation (Wilson 10). Jefferson, a strong

and determined individual himself, upheld his ideas and beliefs about the

structure of the entire educational system.

With his strongly held beliefs and as a member of the Virginia Legislature,

Jefferson took an active role in promoting an improved and more appropriate

education. His "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom" was introduced

in 1779 and passed in 1786 (Arrowood 9). He also

proposed three other educationally related bills, a "Bill for the More

General Diffusion of Knowledge," along with a "Bill for Amending the Charter

of the College of William and Mary," and a "Bill for Establishing a Public

Library" (Arrowood 10). Jefferson described his

philosophy in his "Quixotism" or "Bill

for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge." The bill, describing

his educational system, which consisted of three tiers of education: the

primary level made up of elementary schools, the secondary level which

represented district colleges or high schools in today’s standards, and

the third level composed of a university. His bill included provisions

for choosing school sites and building facilities for the primary and secondary

schools. For the collegiate and university levels, he further included

a selection process for educating the most intelligent students. Moreover,

Jefferson’s education bill upheld his belief that America must educate

all her people (Wilson 10). He stated:

His beliefs are what mark the United States as one of the leading

nations in the world today with education as a fundamental part of its

success. Although his views seemed radical at the time and many questioned

them, Thomas Jefferson remained determined and further expanded his bill

and advanced his thoughts for the reformation of education.

Jefferson detailed his three tiers of education by including the educational process, the type of architecture, and the administration. He divided the state of Virginia into districts, and each district into counties dependent on the population and area (Culbreth 79). For the primary level, Jefferson stated that children, both male and female, should learn reading, writing, and arithmetic. Thomas Jefferson may have developed his opinion that girls should be educated from the time when his father died. Jefferson chose to educate his own daughters so that they not only would have the intelligence to interact in society and educate their own daughters, but also, so that they could direct a course for their sons if their father was lost (Arrowood 177). Moreover, he believed that the public should support every child’s education for three years (Wilson 10). Part of Thomas Jefferson’s reasoning for public support of all children arose from the French liberal, Diderot, who states, "From the prime minister to the lowest peasant, it is good for everyone to know how to read, write, and count" (Arrowood 58). If a child wanted to continue his or her education, it would be at the family’s expense (Wilson 10). However, Jefferson also believed that society should continue to support poor boys with talent in higher education if they proved their abilities (Arrowood 58). A board of electors would choose the location for the primary school buildings and keep the school buildings in good repair (Wilson 10). He mentioned his belief that the school should be located in the center of about one hundred people (Culbreth 79). Jefferson further envisioned the building as a log schoolhouse (Wilson 10). This was not the first time Jefferson encountered the image of a log house for a grammar school since he spent two years of his own education at a classical academy headed by the Reverend James Maury in a log house (Randall 21).

On the secondary level, Jefferson explained that students should learn

Greek, Latin, and higher mathematics. The overseers should make sure that

the school was held in a house of brick or stone with offices. Jefferson

thought that the building should also contain a room for the school, a

hall to dine in, four rooms for a master and usher and ten to twelve rooms

or dormitories for students. He again emphasized the need for a central

location (Wilson 10). However, it was Jefferson’s

ideas about the university level that amazed many and were ultimately carried

out. A dream that he began with William and Mary but never completed, Jefferson

expanded and improved. The fact that he did not return to his expansion

plans for William and Mary may have occurred as a result of his time in

Paris where some of the intellectuals there opened his mind to more liberal

systems of education and where he viewed many extraordinary, Neo-Classical

architectural structures (Culbreth 80).

IV. Jefferson’s Architectural Influences and Planning of a University:

Besides the buildings Jefferson observed in France, the handbooks he read, especially Palladio’s, and the examples of American colleges existing at the time, Jefferson may have obtained ideas from hospitals built in England. As a former student at the College of William and Mary, Jefferson was probably exposed to the fact that the Wren Building was modeled after the Chelsea Hospital. Since Jefferson was already concerned about the filfth and spread of illness common in tight, closed-in spaces, the idea of a hospital may have sparked his interest in exploring ways to prevent the spread of disease (Woods 275). The Royal Hospital at Plymouth, illustrated in John Howard’s State of Prisons in England and Wales, reflects many of the elements Jefferson uses at his university. Similar to Jefferson’s plans, the Royal Hospital had eleven buildings arranged around a square but were detached to allow for the circulation of fresh air (Woods 275). The fact that hospitals must accommodate a large amount of people living in one area is similar to the college environment where students live together in concentrated areas on campus. Students must remain healthy, have room to study, and must maintain order (Woods 277). Thus, Jefferson’s ideas for the academic village may have arisen from the functionality of hospitals and not just the hotels he saw in France.

After returning from France and when L. W. Tazewell requested ideas

from Jefferson for a university proposal, Thomas Jefferson was well prepared.

His plans in 1810, similar to the improvements he wanted to make at William

and Mary, described the arrangement of houses around an open square of

grass. The bottom floor of each house would contain a hall for classes

while the top floor would have two rooms for a professor and family to

live in (Wilson 11). Jefferson’s plans were revolutionary

since the universities of the time were all contained in single buildings,

such as the Wren building at William and Mary. Jefferson remarks on these

narrow-minded views and people’s mistaken perceptions when he states:

Thus, Jefferson’s vision of a university as an academic village

began. His ideas for such an aspiring project evolved from his life as

a student and the several diverse experiences he had throughout his educational

career. The comments he makes about his dislike for the setup of William

and Mary provide evidence for his attempt to correct his own educational

experience for future students. Jefferson comments, "…the whole of these

arranged around an open square of grass and trees would make it, what it

should be in fact, an Academical Village, instead of a large and common

den of noise, of filth, and of fetid air" (Wilson 11).

Jefferson’s determination to change the educational system, sparked from

his own experiences, can be understood as his plans began to unfold.

Jefferson embarked on a more active role to build his dream by promoting his revolutionary college to other learned men. On January 18, 1800 Jefferson wrote his talented colleagues, Dr. Joseph Priestly and Dr. Thomas Copper, "We wish to establish in the upper district of Virginia, more central than William and Mary College, an university on a plan so broad and liberal and modern, as to be worth patronizing with the public support, and be a temptation to the youth of other States to come and drink of the cup of knowledge and fraternize with us" (Culbreth 81). As he gained more support, Thomas Jefferson was elected Trustee for Albermarle Academy on March 25, 1814 (Culbreth 86). When Jefferson presented his plan, it was similar to the one given to Tazewell, but more explicit. He describes the quandrangle, but mentions nine pavilions placed around three sides of a square. He shows each pavilion flanked by ten dorms with covered walkways that connect the buildings (Wilson 13). His work succeeded in February of 1816 when the Bill for Central College passed and a board was established with six visitors responsible for raising money (Wilson 14). They were to use Albermarle Academy as the basis for the College (Dabney 3). On April 8, 1817, the site for the college was selected (Wilson 15). It was here that Jefferson bought two hundred acres of land, located one mile West of Charlottesville, for fifteen hundred dollars from John Perry (Culbreth 92). On May 5, 1817, the Board of Visitors approved the building of one pavilion for that year (Wilson 15).

However, Jefferson did not stop at merely establishing a local college. He wished to establish a university that would represent the entire state. As a result, Jefferson, along with Joseph Carrington Cabell, a member of the Board of Visitors, fought in the General Assembly to establish a State University against their opponents, the William and Mary College alumni. During this time, the College of William and Mary had deteriorated from its initial reputation. Its decline helped to support reason for passing a Bill in 1818 to establish a State University. Thomas Jefferson, chosen among twenty-four commissioners, searched for a location (Dabney 3). The commission voted to establish the university near Charlottesville since planning for a college in the location was already underway. After rallying support and finally convincing members in the legislature to approve the plans for the University of Virginia, Jefferson moved to the next task: the actual planning and building of the physical university.

Thomas Jefferson’s views and experiences of education generated his

unique organization of the buildings at the University of Virginia. However,

after surveying the site for his Academical Village, he found that the

land sloped in two different directions, creating a much narrower space

than his original plans required. As a result, Jefferson rearranged his

plans, making two parallel rows closer together by removing the buildings

on the North end and leaving room for one building of significance (Wilson

18). With an image of the University in mind, Jefferson began work

on the details of its individual architectural pieces.

V. Jefferson’s Setup of the Lawn and Pavilions at the University of Virgnia:

Today, on two acres of land, the puzzle reveals its picture with two parallel rows of two-story pavilions on the East and West Lawns. Five pavilions in each row are connected by one-story colonnades, which are comprised of white plastered columns of the simple Tuscan order. Behind the colonnades are student rooms (Hogan 28). The pavilions on the West Lawn are numbered oddly while those on the East Lawn are numbered evenly. At the North end stands a prominent structure that holds the library, the Rotunda. When standing at the Rotunda and looking out over the Lawn, the pavilions appear equally spaced as the two rows look as though they widen (Hogan 45). However, this is only an optical illusion. Thomas Jefferson increased the distance between the pavilions by adding more student rooms as the pavilions were built further away from the Rotunda. Therefore, four student rooms lie between pavilions II and IV while there are six student rooms between pavilion IV and VI (Hogan 44). As one stands on the south side facing the Rotunda, the rows of pavilions appear to converge, accentuating the centerpiece of the Rotunda (Hogan 45). Thomas Jefferson, however, was not concerned only with "optical illusions" in designing the University of Virginia. The wooden railings above the colonnades become higher toward the South since Jefferson understood that an object looks smaller the further away it is. Thus, as one stands at the Rotunda and looks south, the railings appear to be the same height (Hogan 45). The lawn and the pavilions provide one with the knowledge of Jefferson’s dream for education. Little by little he fit the pieces together into the beautiful picture and ideals students enjoy, even today.

When it came time to sitting down and drawing up plans for his first

pavilion, Jefferson fell short of architectural resources. He had sold

his architecture books to the Library of Congress to replace those burned

in the War of 1812. Consequently, Jefferson had to seek outside assistance.

For ideas, he contacted two old architectural friends with whom he had

collaborated on the United States Capitol and the President’s House, Dr.

William Thornton and Benjamin Henry Latrobe (Wilson 16).

In his letter to these men, Jefferson wrote:

After receiving Thornton’s reply, which contained drawings of two

variations for a pavilion façade, Jefferson chose to follow Thornton’s

design for the first building (Wilson 21). On October

6, 1817, the cornerstone for the first pavilion, Pavilion VII, was laid

in the presence of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe (Hogan

107). A few days later, however, Jefferson received Latrobe’s drawings.

After reviewing these plans, Jefferson decided that he would not only use

two of his drawings for other pavilion facades, but he would also use the

same two-story motif without a lower colonnade on the rest of the pavilions

instead of Thornton’s plans (Wilson 21). With his

plans underway, and as the construction was carried out, Jefferson proved

his concern for the precision of the pavilions, as he was continuously

present on the grounds.

If he could not be present, Jefferson could watch from Monticello through

a spyglass (Dabney 4). As Jefferson watched the first

block laid, the complete image of his university became clear.

Although he used Thornton’s plans as a foundation, Jefferson modified the proportions and orders, using the classical motif of the "Doric of Palladio" for Pavilion VII (O’Neal 16), which stands with a one-story portico on the upper floor and is the only pavilion with an arcade on the bottom floor (Hogan 106).Six one-story Doric order columns were built above six square plastered piers that make up the five-arched arcade (Hogan 107). By using a motif in which Pavilion VII has an arcade surmounted by a colonnade, Jefferson insightfully presented his students with a way to compare the arcade and colonnade. The arcade front provided for the continuation of the covered passageway (Brawne 29). Within the pediment, lies a lunette that matches the Rotunda arcade lunettes. The deep gallery, upper center door with flanking windows, lower center door, triple-sash windows of the classroom, and the family entrance on the right side of the building, are all features Jefferson incorporated into the other pavilions (Hogan 107).

In 1824, Pavilion VII served as the university’s first library. At the age of eighty-one, Jefferson compiled a catalogue of 6,860 books, which served as the University's first library. In 1826, when the Rotunda was completed, these books were moved to the Doom Room. However, for years, Pavilion VII was known as "The Old Library." Pavilion VII also served as the location for faculty meetings and for the center for religious activities. On April 23 1907, forty-two men founded the Colonnade Club to encourage social interaction among faculty and alumni, ultimately promoting the welfare of the school (Hogan 110). Many expansions were added to the building, the most significant of which was in 1913 when its present-day reading room, eight additional bedrooms with bathrooms, and more rooms encroached on the space of the garden to the rear of the pavilion (Hogan 111).

Switching from Thornton’s colonnade motif to Latrobe’s two-story motif, Jefferson began the rest of the pavilions. Students could clearly identify the two different motifs illustrated when comparing the rest of the pavilions to Pavilion VII. Jefferson demonstrated a simple example of the two-story classical motif when he designed temple fronts on Pavilions I, II, and IV at the north end of the lawn. By using this façade on the three pavilions, Jefferson could demonstrate the effects of different architectural techniques and ornamentation (Illustration 16). For instance, the ornamentation of the frieze on each building differs and each provides a softer or harsher contrast.

The construction of Pavilion I began in 1819 and was completed in 1822, making it the fifth pavilion finished (Hogan 96). Jefferson modeled the exterior of Pavilion I on the Doric order of Diocletian's Baths in Rome from Chambray’s book. In the frieze, on the metopes between the triglyphs, Jefferson used the head of Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture. This design seems fitting for a farmer from the backcountry of Virginia and a member of a state relying on agriculture. William Coffee from New York modeled and cast the metopes (Hogan 96).

Pavilion I has four two-story columns. The portico they create is capped by a pediment and is the same width as the pavilion. The columns on Pavilion I are spaced wider than on other pavilions, and they are plastered, painted white, and sit on top of conventional Roman bases of concrete and stand below Doric capitals of painted concrete (Hogan 96). Both the bases and capitals were made in Charlottesville (Brawne 30). The tympanum of the pediment contains a semicircular lunette, again providing a relationship with the Rotunda and other similar pavilions. A square chimney emerges from the center of the roof. Jefferson used iron-tie rods, suspended from the pediment and situated behind the columns to support the upper gallery. The gallery’s white wooden railings contain variations of Chinese trellis designs (Hogan 96). By including such variations side-by-side, Jefferson presents to his students the different designs of the trellis. Center doors open to each floor and are flanked by double-sash windows, one on each side (Hogan 96). The doors were grained with a reddish brown paint to provide a resemblance to mahogany, which was too expensive to use (Brawne 41). This pavilion is an example of a central block of a Palladian building minus the flanking parts (Hogan 96).

The first occupant of Pavilion I was Dr. John Patton Emmet, who was born in Dublin as a nephew to an Irish patriot who immigrated to America. Emmet was one of the eight original professors. Beginning at age 29, he taught natural history and chemistry (Hogan 96). He attended West Point, where he also taught mathematics. He earned an M.D. in New York. Much to Jefferson’s satisfaction, Emmett also had a love of botany and as a result, Jefferson often consulted him about the university’s botanical gardens. Jefferson later asked Emmet to teach zoology, geology, and mineralogy, in addition to natural history and chemistry. Emmet became angered when Jefferson added botany to his teaching expectations (Hogan 98).

As an educator, with a mind for how one should go about presenting architecture to students, Jefferson planned the placement of the Doric order of Pavilion I across from the Ionic order of Pavilion II and next to the Corinthian order of The Rotunda (Hogan 95). Thus, with a simple turn of the head, one could compare the three orders. Like Pavilion I, Pavilion II exemplifies the Roman Revival Style with its three bay full temple front (Hogan 46), and Jefferson could easily demonstrate to his students, similarities and differences in order, decorations, and measurements. The façade of Pavilion II is Palladio’s Ionic order modeled after the Temple of Fortuna Virilis in Rome. Many of the other features of the building also resemble aspects of this Temple (Hogan 46). The frieze displays carvings of ox skulls and cherubs linked by garland (Brawne 39). The two-story freestanding columns are built with white plastered brick and set forward from the colonnade to give them emphasis. They are topped by Ionic capitals made of Carrara marble received from Italy. As with Pavilion I, its columns do not support the gallery as evidenced by the four-inch gap between the columns and the gallery’s edge. Instead, four iron tie-rods suspended from the pediment support the gallery (Hogan 47). To have continuity with the Rotunda, Jefferson placed a fanlight semicircular window, also seen in Pavilion I, in the flat surface of the pediment, which mimics the fanlight windows in the underground passageway of the Rotunda. He continued this treatment of the fanlight rectangular window over the double front doors on the bottom floor. He added to the symmetry of the building by placing the gallery door over the lower door and the upper front windows over the lower front windows (Hogan 46). By so doing, Jefferson created complimentary verticality to the columns through the appearance of tall openings. Jefferson placed a Chinese trellis railing on the gallery (Hogan 47).

The first occupant of Pavilion II was Dr Patton Emmett. He taught natural history and chemistry but soon moved across the Lawn to Pavilion I. The first permanent professor residing at Pavilion II was Thomas Johnson who taught anatomy and surgery. Later Dr. James Cabell, also a professor of anatomy and surgery, would occupy the pavilion for 53 years (Hogan 49).

Pavilion IV, like Pavilions I and II, also has a three bay temple front. It is classically decorated after the "Doric of Albano from Chambray" (Hogan 50), and students could compare the Ionic order of Pavilion II, not only to Pavilion I, but also to Pavilion IV. Moreover, Jefferson allowed students to observe some different effects by using double-sash windows on Pavilion II and the triple-sash windows on Pavilion IV. Also, Jefferson used semicircular windows in all three pavilions; however, Pavilions I and II contain a lunette, while Pavilion IV contains muntins arranged in a multiple arch pattern (Hogan 52). Although Thomas Jefferson’s drawings show the main door in the center, the door was moved to the left, after classes were moved to the Rotunda and when the first floor became a living space. Four columns painted in white are surmounted by Doric capitals and rest on bases made of concrete in Charlottesville (Hogan 52). In the upstairs parlor, the Ionic frieze matches the mantel, which is the only time Jefferson employs this design (Wilson 35).

The first occupant of Pavilion IV was George Blaettermann and his English wife. Blaettermann was 43 years old, making him one of the oldest professors at the University. Born in Saxon, he arrived in January of 1825 to accept the position of chair of modern languages. Although he was extremely intelligent, with a capability of teaching nine languages, he was unable to get along with faculty, students, and even his wife. In 1835, Blaettermann painted the front of Pavilion IV with red paint, a faded remnance of which is still visible today. After fifteen years of outraging faculty and students, Blaettermann was dismissed in 1840 (Hogan 52).

Across from Pavilion IV, stands Pavilion III, the second and most expensive of the pavilions. It differs from all of the other pavilions with its two-story portico designed in such a way that it is narrower than the front façade of the pavilion (Brawne 13). Like the full temple front pavilions, Jefferson places Pavilion III in a specific location. Students could easily observe the differing architectural effect of a projecting portico exhibited by Pavilion III versus the full three bay temple fronts of Pavilion I, II, and IV. (Illustrations 22 + 23)

The fact that Jefferson abandoned Thornton’s ideas as seen in Pavilion VII, for those of Latrobe's two-story columns, is easily seen in Pavilion III (O’Neal 17). Jefferson took this classical motif of "the Corinthian of Palladio" from Leoni’s edition of the Italian architect’s works. Because the columns stand closer together, less of the trellis railing on the gallery is visible (Hogan 100). At Jefferson’s insistence, Italian masons tried to use local stone to carve the capitals, but the stone did not carve well. Consequently, the Corinthian capitals were made of Carrara marble, like those of the Rotunda, and carved in Italy with acanthus leaves (Hogan 100). The fact that the capitals were carved in Italy may be the reason for the pavilion’s large expense (Brawne 13). Hand-carved wooden modillions, an ornamented bracket used in series under the cornice and pediment, repeat the acanthus leaf motif. The modillions rest above the egg-and-dart moldings over dentils (Hogan 100).

Pavilion III originally had two front entrances, a center door leading into the classroom and a side door, which acted as a family entrance, opening into a narrow hallway. Window details such as the tansom, a small hinged window above the door, that mimics the fanlight window of the pediment, are missing from Jefferson’s drawings (Hogan 100). This pavilion, like the others, has a single center chimney to provide consistent symmetry. A parapet remained on top of the roof, as it did on Pavilions VIII and X, to enhance the building’s cubic form until 1870 when it was removed as a result of water leakage problems (Hogan 101). (Illustration 33) It is the only pavilion that was not enlarged (O’Neal 116). Although Jefferson notes that Pavilion III was completed by September 30, 1821 along with Pavilion VII also begun in 1817, and Pavilions II, IV, V, and IX begun in 1818, it was the last pavilion occupied (Hogan 40, 101).

On the interior of Pavilion III, Jefferson used designs similar to those at Monticello. He designed an entablature in the upstairs parlor that resembles the entrance hall at Monticello. He also placed a semi-circular arched doorway in the hallway of the pavilion similar to the library at Monticello (Wilson 25). Thomas Jefferson envisioned Pavilion III as the School of Law. He chose Francis Walker Gilmore as the chair for the school. However, Gilmore was delayed in Europe while recruiting other professors and ultimately died upon returning to Virginia. As a result, Madison nominated John Tayloe Lomax from Fredericksburg for the unfilled position. John Tayloe Lomax was the first to occupy Pavilion III. He was born in Port Tobacco, Carolina County and graduated from St. John’s College in Annapolis at the age of sixteen. Lomax, the only native-born Virginian on the original faculty, arrived a few days before Jefferson’s death. He remained in the pavilion until 1830 when he resigned from the college to become a judge in the circuit court. In the early 1900’s Pavilion III was converted into the Office of the Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences with rooms left open for seminars. In 1925, Pavilion III became the birthplace of the Virginia Quarterly Review, a national journal of literature. Professor James Southall Wilson founded the journal in the small basement room of the pavilion (Hogan 102).

Instead of designing the rest of pavilions with four columns, as he did those toward the north end of the Lawn, Jefferson planned Pavilions V, VI, and VII with six columns. By building Pavilion V next to Pavilion VII, Jefferson allowed students the ability to compare the architecture of a building with six two-story columns to a building with six, one-story columns, respectively. Also, one could contrast the effects of the lower arcade on Pavilion VII to the two-story motif of Pavilion V. (Illustration 25) In addition, Pavilion V lacks a pediment yet it is placed between the pediment of Pavilion VII, which is the full width of the building and the pediment of Pavilion III, which is narrower than the full front of the building. Thus, students could easily see the different uses of a pediment and no pediment at all. (Illustration 26)

With its six columned portico, Pavilion V is modeled after "the Ionic of Palladio" from Leoni’s edition of 1721 (Hogan 103). Thus, students could compare the Ionic order of Pavilion V with the Corinthian order of Pavilion III placed beside it. Pavilion V was the third pavilion built (Brawne 17). The marble capitals topping the columns were carved in Italy. Paying close attention to detail, Jefferson designed the building with dentils and egg-and-dart molding over a plain entablature. Rosettes rest between the uncarved modillions (Hogan 103). Jefferson’s drawings also show the arrangement of the windows in which five bay windows were placed on the upper floor without any indication of a center door with four triple-sash windows flanking the center door on the bottom floor. The windows have louvered blinds, and a Chinese trellis railing runs along the upper gallery, a common theme among many of the pavilions. Again, Jefferson allows for architectural illustration by using three contrasting trellis patterns (Hogan 104). The first tenant of Pavilion V was George Long, a professor of ancient languages. After attending Trinity College and Cambridge, he moved into Pavilion V in December of 1824 at the age of twenty-four (Hogan 104).

Pavilion VI, also unique among the pavilions, has a pediment unsupported by columns. This arrangement is in direct contrast to the rest of the pavilions in which all pediments are supported by columns and easily seen when compared to the temple front of Pavilion IV to the left. (Illustration 29) Situated across from Pavilion V, students again could observe the pediment on Pavilion VI and the hipped roof on Pavilion V. Also, students again could observe the use of two storied columns and one storied columns. (Illustration 28)

Jefferson modeled the façade of Pavilion VI after "the Ionic of the Theatre of Marcellus from Chambray." He continued his use of the Ionic order in the entablature. However, Jefferson uses one-story Tuscan columns to continue the colonnade (Hogan 54). Once again, Jefferson positioned this pavilion in such a location that the observing student could learn much about architecture by comparing and contrasting it with its neighboring pavilions. Its Tuscan order could be compared to the Doric order of Pavilion IV on the left, the Ionic order of Pavilion V across the lawn, and the Corinthian order of Pavilion VIII to the right. The pediment and lower door both have fanlights but of different designs. Jefferson also placed two double-hung sash windows on each side of the upper and lower doors. The front windows also have louvered blinds (Hogan 55). The terrace of the building is slightly elevated with steps at each side (Hogan 54).

Jefferson hired separate contractors for brickwork, masonry, plastering, painting, glazing and the tin plate covering the roof. Jefferson felt that the use of tin instead of shingles on the roof would be more durable (Brawne 46). Richard Ware from Philadelphia was in charge of the bricklaying and brickmaking for Pavilions II, IV, and VI. Pavilion VI was completed without plastering in October of 1822 (Hogan 55).

The first professor to live in Pavilion VI was Charles Bonnycastle, a twenty-eight year old bachelor who arrived from England in February of 1825. Educated at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, he first taught natural philosophy. In 1827, Bonnycastle transferred to mathematics (Hogan 55). Bonnycastle served as chairman of the faculty from 1833 to 1835. He died in 1840 at the age of forty-four and was buried in the university cemetery (Hogan 57).

Pavilion VIII, although it has one-story columns on the colonnade, shows a remarkable contrast to Pavilion VI in that it does not contain a pediment. Pavilions VIII and IX are the two buildings units which Jefferson most likely incorporated Latrobe’s suggestions. Both have recessed entrances, which follow the classical model provided by the Corinthian of the Emperor Diocletian’s Baths from Chambray (Hogan 58). (Illustration 31) In his notes, Thomas Jefferson writes, "Latrobe’s Lodge Front" for Pavilion VIII, indicating the likelihood of Latrobe’s influence (Brawne 18). The pavilion has four two-story Corinthian columns made of brick covered in white plaster (Hogan 58). The columns were originally freestanding which allowed for the entrance of light in the recessed entrance on both upper and lower floors (O’Neal 22). The two columns on the end are half-columns because Jefferson designed them to fit against the wall of the recessed entrance. Students may also see the Corinthian order of the marble capitals, carved in Italy, and on the entablature. The concrete bases of the columns were made locally (Hogan 58).

A parapet on Pavilion VIII originally concealed the semi-flat rooflets, it was removed due to leakage. (Illustration 33) Builders later replaced it with a hipped roof. The two projecting bays on the façade create the recessed entrance. Both bays contain an arched window on the lower floor. An additional arched window also flanks each side of the doorway (Hogan 59). On the upper floor, Jefferson placed a double doorway with two small double-sash windows without arches on each side. All the windows have louvered blinds. Jefferson again provided the building with detail by designing an elaborate cornice lined with sharply carved modillions. Beneath the cornice lies an egg-and-dart molding over dentils. William Coffee from New York executed the cornice (Hogan 60).

Professor and Mrs. Thomas Hewett Key were the first to occupy Pavilion VIII in February of 1825. Professor Key attended Trinity College, Cambridge, and studied medicine in London. He acted as chair of mathematics for two years until he left for the University of London where he became the founder of the London library. Many professors lived in Pavilion VIII (Hogan 60). One of the most famous was William H, Echols, who also served as professor of mathematics. His nickname "Reddy" evolved after his heroic contributions during the Rotunda fire. In the 1950’s, President Darden moved his office from the upstairs of Pavilion IV to VIII and stayed there until 1984. Today, the President’s office is in Madison Hall. After President Darden left in 1884, the upstairs of Pavilion VIII was converted into two faculty apartments with conference space downstairs, a return to Jefferson’s ideal of living and learning (Hogan 61).

Jefferson cleverly situated Pavilion X, which contains a projecting portico that is narrower than the rest of the building, next to the recessed entrance of Pavilion VIII. Thus, once again students could observe their very prominent differences. (Illustration 31) Pavilion X, modeled after the Doric order of the Theater of Marcellus from Chambray’s book, stands with four columns and a pediment (Hogan 62) Jefferson also placed a design on the soffit or underside of its cornice, which demonstrates his careful attention to detail of the Ancients. (Illustration 34) The soffit is lined with rectangular blocks, with each block containing a design of eighteen guttae or eighteen truncated cones. In between the blocks are foliated ornaments of lead in a diamond shape, within which rests a four-petaled rosette. Some believe that the rosettes may be representative of the dogwood blossom, Virginia’s state flower. He topped the entablature with dentil moldings. Jefferson, inspired by the Temple of Nerva Trojan, placed a parapet on Pavilion X, and like Pavilions III and VIII, it was removed in 1870 due to water leakage. (Illustration 33) The Doric capitals were made locally.

Pavilion X is unique among the other pavilions since its columns do not have bases. In designing the columns in this manner, Jefferson exhibited for his students the contrast between the Roman inspired columns of the other pavilions and Greek style bases, as presented in Pavilion X. Instead of a full base, Jefferson placed a square concrete base three inches above the brick floor. The gallery, half the width of the other pavilions, is supported by tie-rods and possesses a trellis railing. The pediment contains a lunette of the conventional fanlight pattern.

The first occupant of Pavilion X was Dr. Robley Dunglison, a Scotsman who at the age of twenty-six arrived with his wife in February of 1825. Dunglison received medical degrees in England and Germany and a diploma from the Society of Apothecaries. Dunglison was the first full-time professor of medicine at an American university and the first to give out medical diplomas issued in English instead of Latin (Hogan 64). Among his other accomplishments, Dunglison also became the first secretary of the faculty and in 1826, the faculty chairman. He later wanted an anatomical building for his dissections so Jefferson began drawings of an "Anatomical Theatre" before March 4, 1825. By including a skylight above the operating area and lunette windows, Jefferson made sure that ample light entered the building. The "Anatomical Theatre" was completed in February of 1827 but destroyed in 1938 for the erection of the Alderman Library. The fact that Jefferson trusted Dr. Dunglison as his personal physician provides evidence for their close relationship and mutual respect. Dr. Dunglison was present when Jefferson died on July 4, 1826 at 12:50 PM (Hogan 65).

Pavilion IX is unique among the rest of the Pavilions, with its prominent domed one-half arch. In addition to using the Roman Ionic order from Palladio of the Temple of Fortuna Virilis for features of Pavilion IX, as he did in Pavilion II, Jefferson showed the influence of French Neoclassism of the Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s Hôtel de Guimard in Paris. Jefferson’s deep regard and admiration for French neoclassical architecture inspired him to include an example for his students. On his drawings for both Pavilions VIII and IX, Jefferson makes indications of Latrobe’s influence on their low-hipped roofs (Hogan 112). Latrobe may have also directed Jefferson’s attention to the most unique feature of Pavilion IX, which gives away its French neoclassical motif. The exedra is the white plastered half-domed doorway of the entrance (Wilson 62). The entrance is recessed into a semicircular niche in the weathered brick walls. The curved, semi-dome above the line of the balcony allows for the entrance of light (Brawne 26). The recessed semi-dome entrance would allow students an illustration of a technique of classical architecture not represented anywhere else in the buildings at the University.

With his arrangement of the pavilions, Jefferson provides students the ability to see the differences between the recessed dome entrance of Pavilion IX in comparison to the recessed entrance in the façade of Pavilion VIII. (Illustration 36) Jefferson ingeniously positioned the French inspired architecture of Pavilion IX across from the Greek architectural example of Pavilion X. Jefferson placed both of these structures at the south end of the lawn since the rest of the pavilions demonstrate Roman architecture. (Illustration 37) Furthermore, the two singular student rooms, one on each side of the south ends of Pavilions IX and X appear like wings (Hogan 64). However, one may also interpret the extra student room on the south end as the beginning of an extension of the university (Brawne 42).

Two Ionic columns and pilasters frame the doorway of Pavilion IX. With little room left, as a result of the prominent entrance, Jefferson placed four triple-sash windows, one on each side of the entrance, and then placed two above them. One single line of dentils and a plain entablature marks the building (Hogan 113). "It could be argued that Jefferson placed the most classical pavilions near the Rotunda and the most clearly neoclassical ones at the open, southern end" (Brawne 26).

George Tucker was the first to reside at Pavilion IX. He was forty years old and soon became the most popular among the original professors. A native of Bermuda, at the age of twenty, Tucker left to attend William and Mary College. There, his cousin, St. George Tucker, taught him law. In 1802 he married the great-niece of George Washington, Maria Carter. After becoming an American citizen, he settled in Lynchburg and served in Congress for three years. Madison, after reading one of Tucker’s volumes of essays, recommended him to Jefferson as a professor of moral philosophy. Tucker, elected as the first faculty chairman, served a one year-term, and later returned to serve twice more. In 1845, he resigned and moved to Philadelphia to pursue his love of writing (Hogan 113).

In contrast to the complicated and detailed pavilions, the student rooms were designed with simplicity and occur between and around the pavilions to comprise another significant segment of Jefferson’s "Academical Village." Fifty-four rooms are located behind the roofed colonnades and adjacent to the pavilions. While the student rooms on the Lawn face in toward the Lawn, the twenty-seven rooms in each of the arcade Ranges face outward. Jefferson designed all of the student rooms with red brick, in keeping with the brick theme of the campus. Each room measures 12 feet 6 inches square. All have one front door with louvered blinds and a window at the back end to allow for light and cross ventilation. Each room also contains a chimney. In order to reduce the amount of chimneys, Jefferson connected two flues to one chimney in adjacent rooms (Hogan 42). Thus, the student rooms fit within the campus and provided students with private study space.

In addition to and located behind the student dorms and pavilions, Jefferson built six hotels, A, B, C, D, E, and F at both ends and in the middle of the two Ranges (Dabney 10). Corresponding to the student rooms, the hotels face outward. These buildings are larger than the student rooms and served as dining halls (Dabney 10). The food was prepared by an individual hotelkeeper, who leased the building and resided in it with his family (Hogan 72).

Jefferson, in building his university, always kept his mind on his educational ideals. It seems as though Jefferson had an educational purpose for every intricate part of the university. Thus, he did not merely stop with his architectural lessons demonstrated by the pavilions, but continued with additional educational techniques, which he employed in the hotels. Jefferson wanted to use the individual hotel buildings as an opportunity for students to practice their languages. With a passion for French, Jefferson decided that the first hotel should be leased to a French family who would teach colloquial French at meals, and the others should be used for teaching Italian, German, and Spanish. However, Jefferson could not find foreign families qualified to teach within rural Virginia and eventually he settled for other applicants. On October 7, 1826, the Visitors expanded the hotelkeeper’s responsibilities beyond dining to include supplying bedding, furniture, fuel, candles, and washing (Hogan 72).

With Thomas Jefferson’s love of nature, he also took the time to plan out gardens that would enhance the village. Behind each pavilion lies a garden where students and faculty could find peace, enjoy relaxation, and spiritually commune with nature (Hogan 29). Jefferson, known for his gardening at Monticello and Poplar Forest, did not like the highly stylized French gardens similar to those he saw at Versailles. Instead of this cold, formal setting, Jefferson preferred the informal jardin anglais of the French. In the Maverick Plan of 1822-1825, Jefferson placed sixteen gardens behind the ten pavilions and six hotels. Since the hotels were built behind the pavilions, the gardens between the pavilions and hotels were originally shared. The gardens are all lined by brick serpentine walls, (Illustration 41) and as Jefferson’s plans show, serpentine walls also divide the center of the six gardens between the hotels and pavilions. However, Jefferson died before the gardens were completed, and besides his designs for their layout, he left no instructions for their planting (Hogan 80). By following his design for each pavilion, the gardens were laid out so that no two are alike. They are the parks that complete Jefferson’s plans for a true village.

VI. Developing a Functioning University:

When the University first opened, the faculty consisted of mostly professors from Europe, had an innovative curriculum divided into schools, and rejected the idea of organized religion and theological dogma (Dabney 2). Although Jefferson intended for separation of Church and State, he did not discourage religious practice as he set aside a room in the Rotunda for religious services, which students did not take advantage of until 1832 (Dabney 12). However, since Jefferson opposed a direct denominational relationship, no clergymen were employed at the University until 1845 (Dabney 13).

The University’s mission and rules were quite different from contemporary colleges. Each department had a distinct school housed in a pavilion with a professor and assistants (Arrowood 43). Since Thomas Jefferson did not want the university to have a president, the Board of Visitors was forced to develop a new plan. In order to conduct affairs properly and efficiently, they developed a system on October 4, 1824 in which the faculty would elect a chair from one of their own for a one-year term who would preside over the university affairs. The University remained without a president until 1904 (Arrowood 45). The professor and Board of Visitors had control of each school. The University also had no prescribed curriculum (Arrowood 43). On April 7, 1824, the Board of Visitors established a tuition fee that each student was required to pay to each professor in advance (Hogan 42). Students could attend as many schools as they wanted with a minimum requirement of three. They paid for each one they attended (Arrowood 43). Part of the reason for such freedom of decision resulted from Jefferson’s belief that students knew what they could handle (Arrowood 44). Besides his influence over the setup of the college and his architectural plans, Jefferson also wished to personally partake in the students’ education. As a result, he often invited students to dine with him at Monticello in small groups. (Illustration 43) Edgar Allan Poe was one among several students to dine at Monticello, stayed at the University of Virginia for a year. To many people’s surprise, during this time Poe had an excellent academic record and no noted outstanding behavior problems, with the exception of some gambling debts (Dabney 8).

However, Jefferson misjudged the students’ maturity and responsibility when it came to self-government. Jefferson wanted students to have self-government because he believed they could manage themselves and behave since they were from the best families. Unfortunately for Jefferson, the time period gave rise to youth rebelling against authority (Dabney 8). Shortly after the University opened, students participated in riots, drinking, and gambling, all of which Jefferson referred to as "vicious irregularities." Students’ rebellious acts occurred, in part because of their dislike for the fact that the professors were European. On one occasion, when Professor Emmet and Tucker went outside to investigate an uproar, a student threw a brick at Emmet and another student attacked Tucker with a cane (Dabney 8). Since professors felt insecure, Jefferson requested that the Board of Visitors develop strict regulations to govern the students at the University. As their first action, they expelled the students involved in the riot. To prevent future rebellious actions, the Board and Jefferson declared that students were to have curfew a nine o’clock every night, rise at dawn, eat breakfast by candlelight, and wear a dull gray uniform. They also prohibited gambling, smoking, and drinking. To ensure proper savings, students had to deposit money with a proctor who would give out small sums and monitor expenses. Student behavior remained quiet for a time, but even with strict rules and the fear of expulsion, students of the future would continue riots that Jefferson would not live to see (Dabney 9).

Although students could choose their own course of study, The University of Virginia established criteria for admittance and guidelines for graduation. The Board of Visitors established an entrance requirement in which every student applying must be at least sixteen years old (Arrowood 45). When first entering the school, a student was never admitted into the mathematical school. A student was also not admitted to the natural philosophy school if he could not demonstrate knowledge of numerical arithmetic. Furthermore, a student was not admitted into the school of ancient language until qualified by the judgment of the professor (Arrowood 46). Each class within each school administered a semi-annual exam conducted in writing. Students who showed outstanding work on exams were announced to the public as "distinguished" in a particular class (Arrowood 44). Even though courses in English composition and literature were not initially offered until right before the Civil War, students had to pass an exam in English grammar and spelling and also show master of their subject area in order to graduate (Dabney 14, Arrowood 45)

Many significant advancements and achievements have occurred in Jefferson’s

University. The Jefferson

Society, the only know organization, reputed to have been established

in 1825, had a mission of dealing with oratorical pursuits. An elected

student represented its members (Dabney 12).

The first degree of the University was granted in 1828 as a Doctor of Medicine.

In 1831 the University established a Master of Arts. However, this degree,

against Jefferson’s beliefs involving electives, required the completion

of mathematics, natural philosophy, moral philosophy, ancient languages,

and chemistry, to which two modern languages were added in 1833. In 1840

the University established a Bachelor of Laws degree and in 1848 it established

a Bachelor of Arts (Dabney 13). It was Thomas Jefferson

who established this center of learning that is afforded with great honor,

prestige, and success today (Dabney 598).

VII. Summary: The Catalyst for American Public Education and Classically Inspired Architecture:

Besides his ingenious architectural achievements, Jefferson is a man

remembered through history as a remarkable lawyer, skilled politician and

speaker, sophisticated writer, and an Enlightened intellectual ahead of

his time. Although he is known for his meticulous record keeping and as

a well-read man, it is his knowledgeable application to his experiences

and actions that developed him into the complex man, known as Thomas Jefferson.

His studies and strong appreciation of education allowed him to mature

and apply his knowledge. With his own life as an example, Jefferson knew

that education should supply one with a learning ground, where an individual

can acquire a foundation. With the "diffusion of knowledge" to all people,

one can realize and overcome challenges, achieving awareness and skill,

and ultimately furthering America’s success. Through his education and

experiences, Thomas Jefferson not only developed a strong foundation of

knowledge with an overall appreciation for all fields of study, but he

also acquired the skill, maturity, and confidence for the ultimate mastery

in his life’s endeavors: the University of Virginia with its extraordinary

educational

purpose, curriculum, and architecture.

Brawne, Michael, University of Virginia: The Lawn, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, 1994.

Culbreth, David M.R., M.D., The University

of Virginia, The Neale Publishing Company,

New York, 1908.

Dabney, Virginius, Mr. Jefferson’s University:

A History, University Press of

Virginia,Charlottesville, 1981.

Hogan, Pendleton, The Lawn: A Guide to Jefferson’s

University, University Press of Virginia,

Charlottesville,1987.

Mapp, Alf J., Jr., Thomas Jefferson Passionate Pilgrim, Madison Books, New York, 1991.

Nichols, Frederick Doveton, Thomas Jefferson

Landscape Architect, University Press of

Virginia, Charlottesville, 1978.

O’Neal, William B., Pictorial History of the

University of Virginia, University Press of

Virginia, Charlottesville, 1976.

Pierson, William H., Jr., American Building

and Their Architects: The Colonial and

Neoclassical Styles, Oxford

University Press, Oxford, 1970.

Randall, William Sterne, Thomas Jefferson: A Life, Harper Perennial, New York, 1993.

Wilson, Richard Guy, Ed., Thomas Jefferson’s

Academical Village, University Press of

Virginia, Charlottesville, 1993.

Woods, Mary N., "Thomas Jefferson and the University

of Virginia: Planning the Academical

Village," Journal of the Society of Architectural

Historians, Vol. XLIV, No. 3,

October 1985.