“The CVS of [Afro-Caribbean]

Religion[s]”*: Botánicas in Worcester, Misconceptions and

Realities

Coauthors: Ahmed Abdelgadir, Crystal

Almanzar, Michelle Cuddy, Brittany French, William Landergan, Julia Maki,

Maureen McKeon, Joanna Mergeche, Emilia Salamán, John

Sluker

Advisor: Professor Rosa Carrasquillo

We dedicate this paper to Professor William

Meinhofer, who supported this project from its inception.

María Tejeda and Afro-Latin America

History Class at Botánica San Miguel

(photo by Rosa

Carrasquillo)

Introduction

In the United

States, the Latino population is the fastest growing minority group. According

to the 2000 Census, Latinos represented 13.3% of the U.S.

population.1 The Latino population in Worcester is consistent with

the national figures, reported as 15.15% of the city's population in 2000.

Historically, Latinos from the Caribbean, mostly of African descent, settled in

New England. Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and recently Dominicans dominate the

demographics.2 Afro-Caribbean people in New England influence the

communities they settle in, bringing their culture and religions and

establishing businesses of all types.

One of the first

Latino businesses in many New England communities is the botánica which

is an ethnic healing stores that serve Afro-Caribbean religions, especially

Santería and Espiritismo. These religions are often seen as taboo or

primitive or completely unknown to the U.S. public. Historically, these

religions and botánicas have served as “quintessential cultural

mélanges” that with an increasing Latino population in the city

have become increasingly present.3 New York City has 147

botánicas, a sharp contrast to the two botánicas currently open

in Worcester. While the earliest origins of botánicas in New York City

have been traced to the 1900's,4 the first botánica in

Worcester did not open until 1973,5 and their presence has not

developed in a similar manner. This article addresses the contrast by tackling

three main goals: (1) To understand the role of botánicas in Worcester

in comparison to the successful picture of New York City. Why are there only

two botánicas in Worcester when there is a large percentage of Latinos?

(2) To estimate the cultural significance of botánicas in the larger

community, what is the role of botánicas in Worcester? and (3) To

collaborate with the College of the Holy Cross's efforts to improve relations

with the Worcester community. Using personal interviews and participant

observation, data was collected regarding healers and their botánicas in

Worcester, Massachusetts.

Background

Santería or

Espiritismo are part of the African Diaspora to the Americas and have a rich

history. Santería comes from the Yoruba, an ethnic group originating in

Nigeria. The Yoruba believe in many deities (orishas) which like Roman or Greek

gods, have human-like qualities, including flaws and strengths. The purpose of

the religion is to facilitate communication between orishas and humans in order

to establish physical and spiritual balance. In the Americas, these Yoruba

beliefs were masked with multiple aspects of Catholicism, providing a safe form

of experiencing Yoruba religion within the Church.6

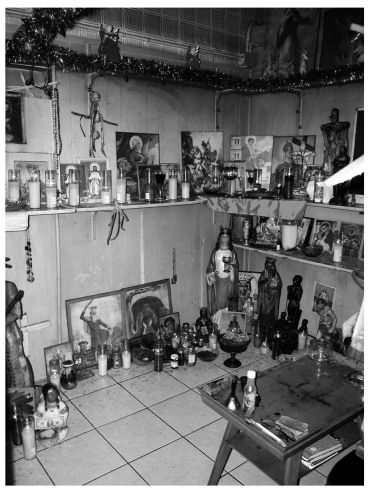

Shrine to Ogún at Steve Quintana's

house, showing the orisha's

connection to metal and weaponry.

(photo by

Maureen McKeon)

Likewise, the

Catholic Church did not approve of Espiritismo, the Caribbean rework of Allan

Kardec's belief system. In the nineteenth century, Europe and the United States

began to experiment with Spiritism, the ability to speak with the dead through

various methods like levitations and table rappings. When Spiritism was

introduced in the Spanish Caribbean, many freethinkers adopted it to express

their discontent with colonial governments. Rapidly, people of African descent,

who found this religion particularly appealing, adopted Spiritism. Affirming

important aspects of Afro-Caribbean worldview, Spiritism offered “new

methods” to communicate with spirits. To facilitate this community an

espiritista, a religious leader, translates what ever the spirits advice in

order to resolve any human infliction.7

Both Santeria an

Espiritista are represented in the botánicas of Worcester. Frank

Rosario, a santero from Puerto Rico, came to the United States when he was

eighteen. He has been in contact with the spiritual world since his youth and

in June 2006 opened Botánica Las Mercedes on Pleasant Street as a result

of a calling he received from the orisha, Obatalá.8

María Tejeda, an Espiritista from the Dominican Republic, and owner of

the Botánica San Miguel, located on Chandler Street, is named for the

saint she associates herself with.9 Ms. Tejeda realized she had the

ability to communicate with the spirits at the age of seven and afterwards, was

instructed by her aunt in the spiritual realm.

The Calling

Each

botánica owner has a unique life-long spiritual calling. Ms. Tejeda

expressed her calling to be a selfless and helpful support system for the

Worcester community. Intending to spend only two months in Worcester, she came

and felt as though someone needed to attend to the problems of Latinos. After

spending ten years in the city, she is content with her influence in the

community. She remarked that she serves as a source of strength and refuge for

those who need support, and also emphasized the beauty and goodness of

Espiritismo.10 Likewise, Mr. Rosario professed a desire to open a

botánica since his youth. He feels that it is his responsibility to

serve as an intermediary between the people and their spirits.11

These

botánicas provide a variety of services for their clientele. On

location, the botánica owners sell an array of perfumes, oils, candles,

statues, cards, mats, and other products. The owners themselves administer

several healing rituals. Botánicas affiliated with Santería, such

as Botánica Las Mercedes, offer consultations, divinatory methods such

as card and shell readings, spiritual masses, community gatherings, and other

spiritual ceremonies. Botánicas affiliated with Espiritismo, like

Botánica San Miguel, also offer consultations, card readings, and

similar healing rituals. Most consultations take place at the botánica

but some of the rituals are held at the homes of the clients. The purposes

underlying these rituals vary from physical healing to spiritual cleansing. In

the process of performing these rituals, the Santeros and Espiritistas

communicate with the spiritual beings to discern the problems at hand. Mr.

Rosario explained that the ceremonies and rituals they perform are meant to

protect the individual, and never to inflict harm upon others. Mr. Rosario

added that because spirits have the potential to damage us, it is important to

conduct practices that will protect ourselves, and this protection is achieved

without harming other people. Occasionally, the botánica owners are

confronted with physical ailments beyond their healing capabilities and

consequently, they must refer their clients to medical

practitioners.12

Prayer candles, perfumes, statuettes of

saints and rosary beads for sale at

Botánica Las Mercedes.

(photo

by Maureen McKeon)

Botánica

owners in Worcester serve as a complimentary component to their surrounding

communities. The Santeros and Espiritistas feel that they have an innate duty

to serve the needs of the community and perceive their efforts and religions to

be truly beneficial for the public. Studies conducted by Sara Trillo-Adams,

director of the Latino Mental Health Project of Worcester, have shown that

Latino populations tend to receive unsatisfactory mental health

services.13 In order to fulfill their responsibilities to the

communities, Santeros and Espiritistas establish botánicas to offer an

alternative to traditional mental health services and provide clients with the

aid they need. As Mr. Quintana remarked, botánicas are the “CVS of

the religion,” offering complimentary mental and physical health services

to Latinos.14 Mr. Quintana and Mr. Rosario, as practicing Santeros,

and Ms. Tejeda, as a practicing Espiritista, came to the United States with

personal aspirations of providing an outlet for individuals in need.

Body, Mind, and Spirit

Although

Afro-Caribbean religions typically attract people of Latino background,

botánica owners provide services to clients from diverse backgrounds

including both Anglo-Americans and African-Americans. Generally these clients

reside in close proximity to the botánica but owners service clients

from all over the United States and even the Caribbean. On average the

botánica owners deal with anywhere between five to ten clients per week,

the majority of which are women.15 Many of the clients are regulars

especially when the botánica has been in business in one area over a

long period. The clientele tend to be older than eighteen, but according to Ms.

Tejeda, clients can be as young as eight years of age.16 People

consult the owners of these botánicas with various issues including

physical problems, seeking spiritual guidance, personal issues, including job

troubles, drug abuse, difficulties in love, and numerous psychological issues.

The fact that

Latinos visit the botánicas for consultation with regards to

psychological issues indicates that they are not receiving adequate mental

health services.17 In fact, responding the early 2000s budget

crisis, Massachusetts “has severely curtailed access services on the part

of immigrants, including legal immigrants.” As a result, “immigrants

became ineligible for federal programs such as health services (including

mental health services), income support, or emergency

services.”18 In 2001, the US Surgeon General reported that

Hispanics and Latinos were one of four groups in the United States that were

receiving inadequate mental health services. To help address this problem in

Worcester, the Latino Mental Health Project was developed. The project began in

2002, and it was designed to be “A collaborative to improve access to

mental health services in the Latino community of Worcester.”19

The Project attempted to find information on Latino's mental health needs,

locate barriers to seeking treatment, and draw information about their

experiences with professional mental health services.20

The findings of

the Project explain why many Latinos have faced problems with mental health

services and receiving appropriate treatment. Eighty-six percent of the

participants in the interviews reported that they or a family member had

experienced a mental health related problem. Many of the conditions that were

reported are understood and accepted by the Latino community, but mainstream

American psychologists and doctors look them at differently. Any belief in the

spirits was diagnosed by professionals as some type of psychosis and was

treated with high doses of medication. Therefore it is not surprising that

twenty percent of participants in the project said they had felt disrespected

when seeking treatment. Another twenty-two percent said they felt negative

effects from medicine that was prescribed to them. The study recognizes that

Latinos do not feel comfortable seeking treatment that requires the use of

modern medicine, which is often ineffective for their specific conditions.

Because of cultural barriers, as well as a lack of health insurance and

language differences, the status of health services in the Latino community is

inadequate. One of the many reasons that Latinos visit botánicas is to

supplement or replace modern mental health services that have not been

successful in addressing the needs of the Latino population.21

The Mental Health

Project also found that a total of fourteen percent of the 166 interviewees

admitted to seeking alternative care for these mental-health related problems

from a Santero or Espiritista.22 About fifty percent of the

interviewees were Puerto Rican and a larger majority was Christian. Many

interviewees may have sought out alternative services but did not admit to it

because they were afraid of being wrongly judged, perceived as uneducated, or

were embarrassed.23

Although some

clients may lack faith in professional medicine, the owners of botánicas

do not hesitate to outsource or recommend that clients seek professional

treatment. The owners usually recommend visits to medical doctors as part of

their consultation, and often will use a doctor's diagnosis to pinpoint where

certain sicknesses are concentrated.24 Ms. Tejeda admitted that

there are certain problems, more specifically physical problems, which she is

not able to cure and consequently recommends that clients with these problems

see a doctor. Currently there are programs, one of which conducted by Boston

University Medical School, which informs doctors about Afro-Caribbean religions

and how to integrate some of the herbal medicines and traditions into modern

professional practice.25 Although the integration between the

Afro-Caribbean religious practices and professional medicine is beginning to

spread, Worcester is still in the early stages.

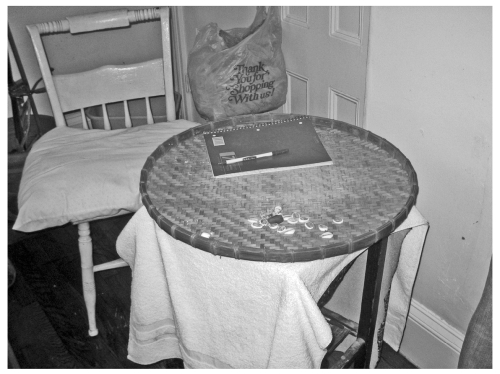

The table on which Steve Quintana performs

shell (caracol) readings for clients. The red notebook is used to document each

reading, so that it can be used to help decipher future readings.

(photo by

Maureen McKeon)

The table in the consultation room where

María Tejeda gives readings

- the deck of cards are tarot cards she

uses for consultations, and below

are the notebooks she uses to record all

of her clients readings

(photo by Rosa Carrasquillo)

Through Community Eyes

While Worcester

boasts a sizeable Latino population, it is currently home to only two

botánicas. There are a total of five listed in the public phone

directory, but only Botánica San Miguel and Botánica Las Mercedes

are still open for business.26 It is surprising that so few of these

religious businesses have succeeded in a city that has such a high

concentration of Latinos, especially those from Caribbean countries, such as

the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. When a comparison is made between the

147 botánicas of New York City, observed in the boroughs of Manhattan,

Brooklyn, and parts of Queens, and the two surviving stores in Worcester, many

questions are brought to the forefront.27 The most prominent query

that surfaces is why it has been so difficult for botánicas to remain

operational in the city of Worcester.

While he success

and influence of botánicas in Worcester seem to be struggling, the nes

in Dorcester are striving. Steve Quintana, a renowned Santero in Dorchester,

uses his house as a center for many religious gatherings. This could present

neighborhood problems, due to the amount of people and the noise level involved

in their ceremonies (many times the batá, a sacred drum set used in

Santería, is played loudly); however, Mr. Quintana boasts that he has

never had encountered negative reactions from the immediate

neighborhood.28

Afro-Latin America class at Steve

Quintana's house.

(photo by Rosa Carrasquillo)

In describing the

role of his botánica in the community, named The House of Mother Nature,

he stated that it was akin to a bodega, a small neighborhood marketplace, but

for religious healing products. He imports many of his herbal products from

Peru, Chile and various Caribbean countries because they cannot be found in the

United States; other products he finds domestically. In his opinion, the most

challenging aspect of owning a botánica is managing the inventory of the

store - he cannot display 15-20% of his products because there is not enough

space in his store. Until recently, the store was located in Jamaica Plain,

Boston, but due to the rising cost of rent, Mr. Quintana was forced to move the

store to 357 Washington Street in Brighton, Massachusetts. The relocation has

been difficult because the Latino community is distanced from the store. He

still believes, however, that curently it is easier to open and maintain a

botánica in the Boston area than it was when he first opened in 1990.

There are ten operational botánicas in Boston, compared with the

existence of only two when he started out.29 Despite the long-term

success of Mr. Quintana's botánica, he has felt the pressures of the

small business economy in Boston. This low rate of success by small businesses

is felt statewide, and is therefore applicable to the Worcester economy.

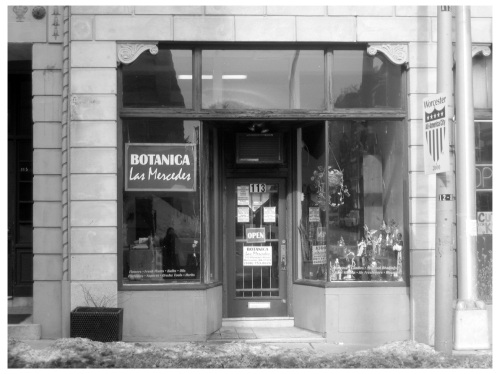

When looking at

one of only two botánicas in Worcester, Botánica Las Mercedes,

Mr. Rosario provided an in depth portrayal of the struggle associated with

operating such a store in the city. He emigrated from Puerto Rico nineteen

years ago and opened his first botánica in June of 2006. For the most

part he feels the people of Worcester have welcomed him, and he has earned

their appreciation and respect.30

When members of

the community were asked to comment on the existence of Botánica Las

Mercedes, a variety of views surfaced. On Pleasant Street, a few storefronts up

the road, is an African American clothing store. When asked about the existence

of its neighboring botánica, the clerk was extremely unwilling to

divulge any feelings concerning it. He stated that he did not want to comment

on someone else's store and somewhat hurried the interviewers out of his

establishment. This silence seems to be highly indicative of the mystique that

often surrounds these religious stores.31

Across the street

from Botánica Las Mercedes, at 10 Irving Street, is All Saints Church.

The ministry coordinator of the church, Sally Talbot, stated that she was aware

of the botánica but was unfamiliar with its exact purpose.32

Ms. Talbot works in the opposite direction of the store and therefore does not

have any day-to-day interaction with it. Because of this she and many of the

other members of the All Saints Church have become oblivious to people coming

and going. She highlights the fact that the neighborhood is one of mixed income

and diversity and the turnover of storefronts is tremendous, especially the

businesses that have occupied where Botánica Las Mercedes is currently

located; there is little parking near the businesses, making it unattractive to

potential customers.

Storefront of Botánica Las

Mercedes

(photo by Maureen McKeon)

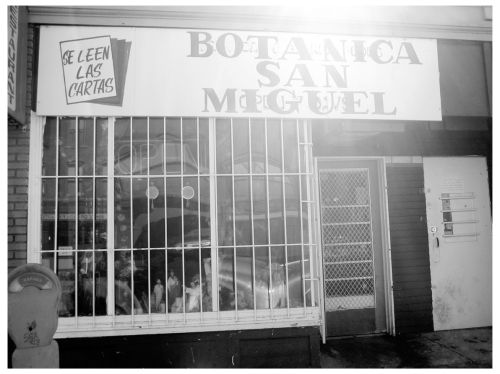

Storefront of Botánica San

Miguel.

(photo by Maureen McKeon)

Bordering

Botánica Las Mercedes on the left is Freddy G's Hair Salon. When asked

about his knowledge of the neighboring store Freddy G explained that he had

never bought anything from them, but sometimes interacted with the store if he

needed change. He also mentioned some common misconceptions of the store,

saying it was involved in voodoo and witchcraft. Overall, however, Freddy G had

no problems with the Botánica Las Mercedes.33

As opposed to

Botánica Las Mercedes, Botánica San Miguel, located on Chandler

Street, has been in business an astonishingly long time considering the

transience of many other businesses in the area. After immigrating to the

United States with the intention of staying for a mere two months, Ms. Tejeda

felt that it was necessary for her to stay and aid the people of Worcester. She

believed there was an immediate need for her in the area and thus established

Botánica San Miguel. Being open for so long, Ms. Tejeda has seen other

botánicas come and go, sometimes even losing customers to new

competition. Still, she is reassured of her status due to the return of many

customers after realizing that her work “is real and of higher quality

than many other places.” Ms. Tejeda boasts of good neighborhood reception

with little to no involvement with the police, neighbors, or violence. To her,

this highlights the fact that she is doing a good job in her religious vocation

by contributing positively to the community. Ms. Tejeda also reiterates that

her line of work is a calling and that money is not important. Her only goal is

to truly help the members of the community who seek her

assistance.34

Adjacent to the

botánica is a Spanish-American restaurant, called El Sazón

Latino, which serves a variety of Hispanic foods; Spanish is mainly spoken at

the establishment. A server, named María, from the Dominican Republic,

was generous enough to comment about her knowledge and opinion of the

botánica. She was fully aware of the existence and intent of the

botánica - that it sold candles, other religious items, as well as

provided spiritual services. She has never received a consultation, but has

entered to purchase various items, such as candles and incense. When asked to

comment on her view of the botánica, she stressed that Ms. Tejeda has

always worked to strengthen the community.35

Further down at

140 Chandler Street resides Edward's Economy Paint Supply. Upon entering the

business, the receptionist, Carol, and older, white woman did not express any

knowledge of the existence of the botánica. She stated that she entered

and exited the paint supply store in a way that rarely took her past the

botánica, so she had not noticed it.36 Her co-worker, Henry,

an older, white man, however, expressed ample knowledge about the

botánica and its perception by the community.37 He is aware

that it exists - on one occasion he entered to buy scented candles to make his

house smell nice, in addition to wanting to “help out a fellow Worcester

neighbor” with his patronage. Henry states that the botánica is a

religious store, but that it practices “their type of religion.” He

explains his view that religion depends on how you are brought up, and admits

that the religion practiced in the botánica seems much more intense and

devout than his religion. Even though he knows that the botánica does

not partake in any illegal activity, he hears people say that they think it is

a drug place - more specifically, a place where marijuana is sold. In his

opinion, the Chandler Street neighborhood causes the botánica to be

associated with such things; he explains that if Botánica San Miguel

were located in the Solomon Pond Mall, people would probably be impressed with

how great the store is. When the social marginalization of community perception

is then added to the already troublesome economic situation that faces the

botánicas in Worcester, it becomes exponentially more difficult for

these businesses to survive.

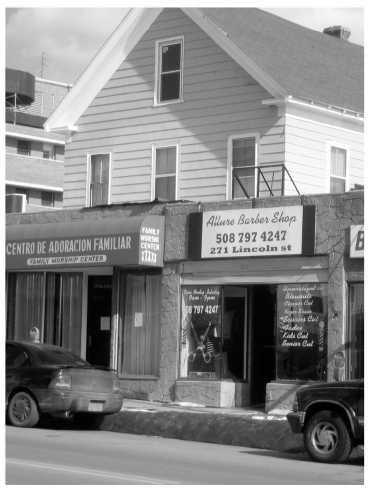

In his inaugural

speech, Governor Deval Patrick recognizes that there exists a, “…

state wide problem that it is extremely difficult for small businesses to stay

afloat after opening.” As a consequence, he vows to stay true to his

campaign platform and create state wide programs that will, “recognize

that most new jobs are created in small businesses, and that we want small

businesses to make it in Massachusetts, too.”38 Governor

Patrick’s concerns are exemplified through the botánicas in the

Worcester community: there are currently five botánicas listed in the

2007 Worcester phone book, although only Botánica San Miguel and

Botánica Las Mercedes are the only businesses that are actually

functioning. For example, Botánica La Milagrosa is listed at 271 Lincoln

Street in the phone book; in a very short period of time – between the

publication of the phone book and February 27, 2007 – this botánica

has already gone out of business and “Allure Barber Shop” has

replaced it.

Storefront of Allure Barbershop, which now

occupies the former

location of Botánica La Milagrosa

(photo by

Maureen McKeon)

Summary of Results

Botánicas

in Worcester offer the same services as botánicas in New York City, but

because of economic factors, it is more challenging to open a botánica

in Worcester than in New York City. Like Anhai Viladrich found in New York, the

role of botánicas in Worcester is complementary to modern

medicine.39 While they are often able to address their physical,

spiritual and psychological problems through the services of to

botánica, practitioners will turn to mainstream professional care

physical ailments requiring surgery or serious treatment, particularly when

recommended in a spiritual consultation. In addition, the botánicas

provide a place of cultural validation and a resource to build community.

Although the

botánica owners were initially hesitant to participate in this project,

the interviews conducted have opened a dialogue between the College of the Holy

Cross and these religious practitioners, and all individuals interviewed

extended an open invitation to return to their stores. The Worcester community

will benefit though Sara Trillo-Adams, Director of the Latino Mental Health

Project of Worcester, who hopes to provide Latinos with other mental health

alternatives by referring to this article.

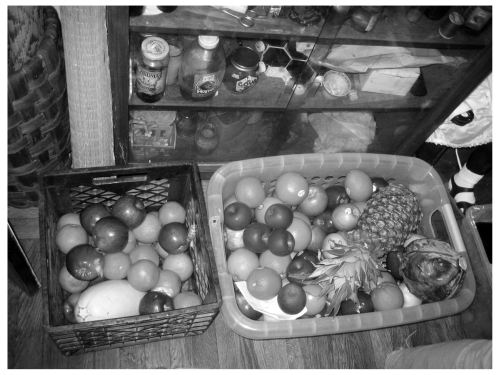

In the baskets there are apples, oranges,

pineapples, cabbages, squash, and lemons

used as offerings to the orishas

in religious community gatherings

at Steve Quintana's house.

(photo by

Maureen McKeon)

Notes

| 1 |

Yoel Camayd-Freixas, Gerald

Karush and Nelly Lejter, “Latinos in New Hampshire: Enclaves, Diasporas,

and an Emerging Middle Class,” in Torres, A. (ed.) (2006). Latinos in

New England. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006, 171-186,

172. |

| 2 |

Camayd-Freixas, Karush and

Lejter, “Latinos in New Hampshire,” 176. |

| 3, 4 |

Viladrich, A. “Beyond the

Supernatural: Latino Healers Treating Latino Immigrants in NYC,”

Journal of Latino/Latin American Studies, 2 (1) (2006): 134-147, |

| 5 |

Crystal Almanzar, Phone

Conversation with Wanda Vega. |

| 6, 7 |

Olmos, Margarite Fernandez and

Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An

Introduction from Vodou and Santeria to Obeah and Espiritismo, New York

University Press, 2003, 171-210. |

| 8 |

Interview with Frank Rosario,

February 22, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 9, 10 |

Interview with Maria Tejeda,

February 24, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 11, 12 |

Interview with Frank Rosario,

February 22, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 13 |

Sara Trillo-Adams. “Latino

Mental Health Project.” Public Presentation. College of the Holy Cross.

February 20, 2007. |

| 14 |

Interview with Steve Quintana,

February 17, 2007, Dorchester, MA. |

| 15, 16 |

Interview with Maria Tejeda,

February 24, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 17 |

Sara Trillo-Adams. |

| 18 |

Miren Uriarte, Phillip J.

Granberry, and Megan Holloran, “Immigration Status, Employment, and

Eligibility for Public Benefits among Latin American Immigrants in

Massachusetts,” in Torres (ed), Latinos, 53-78, 68. |

| 19 - 23 |

Sara Trillo-Adams. |

| 24 |

Interview with Frank Rosario,

October 22, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 25 |

Sara Trillo-Adams. |

| 26 |

Yellow Book: Greater

Worcester, 2006-2007, Business Alphabetical Listings, 20. |

| 27 |

Viladrich, " Beyond the

Supernatural," 158. |

| 28, 29 |

Interview with Steven Quintana,

February 17, 2007, Dorchester, MA. |

| 30 |

Interview with Frank Rosario,

February 22, 2007, Worcester, MA. |

| 31 |

Maureen McKeon, personal

conversation, 27 February 2007. |

| 32, 33 |

Brittany French and Maureen

McKeon, personal conversation, 26 February 2007. |

| 34 |

Interview with Maria Tejeda,

February 24, 2007, Worcester, MA |

| 35 - 37 |

Maureen McKeon, personal

conversation, 27 February 2007. |

| 38 |

“Text

of Governor Deval Patrick's Speech”, Boston.com Local News, 27

February 2007. |

| 39 |

Viladrich, A. “Beyond the

Supernatural: Latino Healers Treating Latino Immigrants in NYC,”

Journal of Latino/ Latin American Studies, 2(1) (2006): 134-147,

158. |

|