Helen Bigelow Merriman: Author and Lecturer

Helen Bigelow Merriman: Author and Lecturer

James Welu, Director Emeritus, Worcester Art Museum

Born in Boston in 1844, Helen Bigelow Merriman was the only child of Erastus Bigelow, an inventor of weaving machines whose company in Clinton, Massachusetts became the world’s largest manufacturer of woven wire goods. In the late 1860s Helen Bigelow and a number of other women studied drawing and painting in Boston under William Morris Hunt. Her classmates included some of the city’s most successful artists, among them Sarah Wyman Whitman, whose posthumous portrait by Merriman hangs at the Radcliffe Institute. Hunt had a tremendous influence on Merriman and helped to mould her outlook on life. She continued to draw and paint throughout much of her life, including numerous watercolors documenting her many travels abroad.

It was in Worcester, where Helen Bigelow Merriman and her husband, Reverend Daniel Merriman, lived from 1878 to 1901, that her deep appreciation of art had its greatest impact. There she taught art, commissioned art work, and collected works by both old masters and contemporary artists. Her deep commitment to art and art education, which was reflected in her carefully crafted lectures for the Worcester Art Society, helped advance an interest in art among many of Worcester’s community leaders that led to the founding of the Worcester Art Museum.

While in Worcester, Mrs. Merriman also pursued writing, an interest she shared with her literary friends Henry James, Annie Adams Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett. Merriman wrote not only about art, such as her 1890 publication What Shall Make Us Whole?, which deals with spiritual healing. Many of her writings are filled with truths about life that she extracted from her artistic training. In Concerning Portraits and Portraiture (1891), she wrote, “Although the artist is not properly a moralizer he gets from his art many side hints about very deep truths.”

While in Worcester, Mrs. Merriman also pursued writing, an interest she shared with her literary friends Henry James, Annie Adams Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett. Merriman wrote not only about art, such as her 1890 publication What Shall Make Us Whole?, which deals with spiritual healing. Many of her writings are filled with truths about life that she extracted from her artistic training. In Concerning Portraits and Portraiture (1891), she wrote, “Although the artist is not properly a moralizer he gets from his art many side hints about very deep truths.”

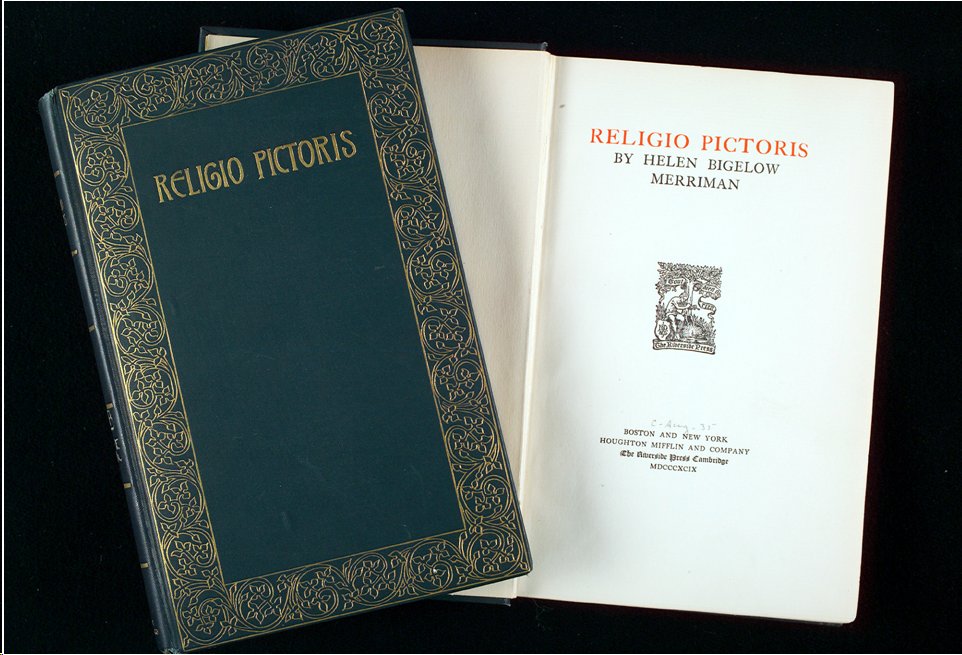

Merriman’s most significant publication, Religio Pictoris (1899), which she dedicated to her husband, was written while they were both helping to establish the Worcester Art Museum. This volume, modeled after Sir Thomas Browne’s seventeenth-century treatise Religio Medici, a reconciliation between religion and science, deals with the links between religion and art. The breath of Merriman’s references are impressive: poetry of Robert Browning, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, classics such as Plato’s Symposium and contemporary novels, such as Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace. She cites St. Paul, “Then I shall know even as also I am known” (I Corinthians 13:12) for her chapter on “recognition.” She quotes both Schiller’s Ode to Joy, 1785 and Dante’s Divine Comedy in the original, as well as references in French. Beginning a chapter on individuality, she cites the concluding lines of Canto VIII of Paradiso (incorrectly listed as Purgatorio) that speak to the importance of paying attention to people's natural dispositions. Society should not try to force people into work for which they are unsuited, but respect their natural inclinations. John La Farge’s Letters from Japan are quoted to reinforce Merriman’s own beliefs in the harmony of the universe expressed in the balanced proportions that inform human activity as diverse as poetry, pottery decoration, painting, or mathematics.

Merriman wrote, “Works of art minister to some of man’s highest needs, and his gratitude rises to preserve them, so that they gain a species of immortality.” It was this philosophy that lie at the heart of the Merrimans’ efforts to help create an art museum for Worcester.

Religio Pictoris (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin and Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge MA 1899) Selections:

(Page 5) We may say then, first, that the artist is pledged to idealism by his very vocation; second, that he is constrained to make account of the essential qualities of material things to a much greater extent than the musician or the poet; and third, that in common with the musician and the poet it is his personality that gives expression to the elements with which he deals. (Pages 9-10) The milliner who trims a bonnet, the artisan who carves a chair, the housewife who makes a pudding, could really teach us the same lessons, for they all work under the same conditions of an ideal to strive for, materials more or less stubborn to handle, and a personal quality which determines the taste of their products. Much is said in these days about handicraft, for people realize as never before that the training of the hand is as essential to harmonious development as the training of the head. We are fast getting over the idea that a man’s brain is the only aristocratic organ he possesses. We discount mere acquisition if it be not put to some constructive use, and all this shows an increasing appreciation of man’s function as a maker; a function to which the exigencies of primitive life impel him without question, but which he is in some danger of forgetting when he is no longer under the pressure of an immediate relation between his daily toil and his daily bread. (Pages 10-11) The necessity to create is strong upon the artist because he sees with inner vision an ideal that he wishes to reproduce. He does not stop to reason about his materials, but bends them impetuously to his service. The average human being, on the contrary, lacking any well-defined inner vision, has little impulse to create. He goes on speculation about the contents of the work in which he finds himself, and fails to understand that material things will yield their final secret only to him who masterfully shapes them into noble life. (Pages 12-13) . . . it is the lifelong struggle of the artist to look at things in a large way, and to see the parts as related to the expression of the whole. The “ensemble” is what he strives to render. The need for this lies at the basis of all impressionism, not merely of the often exaggerated impressionist work of to-day, but of that sound doctrine of impressionism which is the only tenable ground of real art, and which asserts that we should paint, not things themselves, but things in their relation to one another as the relation impresses the mind of the artist. (Page 15) We lose our perspective, we revolve around some detail until we magnify it out of all due proportion and get our lives “out of keeping” or “out of drawing,” as the artist would put it. It would not be difficult to show that ninety-nine hundredths, if not all, of our troubles come from this source; for at the few times when we can “see life steadily and see it whole,” our ordinary trials seem unimportant, and we feel a power to deal with them that we can never have while we are directly in their grasp. This power comes from seeing things in their right relation. The artist simply cannot paint his picture except in view of the whole. He must refer to it to correct his proceedings at every moment. Can we expect to make good lives on any other basis? (Pages 22-23) When . . . . we come to dress, furniture, and buildings, and in these man’s bare recognition of human needs is modified by his desire, in meeting those needs, to express also something of that sense of fine proportion and harmonious color with which he finds himself endowed. Houses, furniture, and clothing of the higher grades are not made in great numbers after one pattern to the extent that tools are. More individuality is expected in the designing of them. Their wholeness is still a personal expression, a recognition of need, but one into which an element of delight has entered, as in the airy caprice of an embroidery that adorns a robe, or a noble tower that soars to the sky, pierced and fretted so exquisitely that the doves which circle round it seem to be a part of its legitimate ornament. (Page 107) Beauty alone is the true, the good, and the permanent. This creed, which sounds at first somewhat pagan, is found to have considerable moral stamina when we discover that what the serious artist means by the beautiful is not the merely melodious, soft, an superficially pleasing, but rather that which has expression, and reveals life and character. Life is the great essential of beauty. A work of art which expresses noble life, which refracts and multiplies our sense of living, even though it do this by painting a corpse, is a beautiful work. (Page 110) The artist’s creed is absolute idealism, so far as his own work is concerned. Not only the life and beauty of things, but their actual existence is a matter of relation. The trouble with him is that he does not often carry his creed to its ultimate conclusion and apply it to morals as well as to art. If he did this he could see that his finest picture, though a whole in itself, is yet but a part of the greater whole of human life, and must therefore express the soundness and health, rather than the corruption and decay of that life, if it would have permanent value. Art, literature, human life itself, twist themselves into many grotesque and unwholesome shapes for want of faith in this simple principle of relation which, once accepted, sends a purifying breeze through all dark and stagnant places. (Pages 137-139) And the same is true of the great conceptions of Deity that we characterize, broadly speaking, as eastern and western thought, though each has its undiscovered disciples in every New England hamlet. Some should naturally adopt the personal conception of God that belongs to the West, while others are more attracted by the idea of the immanence of God that characterizes the thought of the East. Neither contains the whole truth, both have their limitations. Western thought tends to represent God as a sledge-hammer, eastern thought vaporizes Him: or, to carry the figure farther, we may say that western thought fixes on the piston-rod as the efficient force in the engine of life, while eastern thought dwells on the steam. We can see that it takes both to turn the driving-wheels. Both are essential, and in proportion as we relate them to each other we gain a living conception of God. In fact, the mere opening of the mind to admit an opposite view from the one we are naturally identified with seems in itself to reveal to us much of the divine nature. But in adopting the views of our eastern brethren, as is so much the fashion to-day, we must remember that their doctrine needs as much help from ours as theirs gives to us, and therefore, instead of abandoning our past and embracing their ideas as a new and complete revelation, we must stand firm for the truth that is ours by birth and inheritance, at the same time that we open our ears to their message. The whole will be found by means of a fruitful interchange of ideas. Except as we feel the immanence of God, nature is dead to us, and we live in an alien world. Except as we feel the personality of God, both man and nature are orphaned, and expediency becomes the only rule of conduct. But we may have all the good and escape all the evil that is threatened by either view when taken by itself, if we see the living God as the union of his two attributes, as constituting, pervading, and renewing nature and the physical life of man, its highest form; and at the same time as linking all beings together through the interior principle of relation so that his ear is open even to a sparrow’s fall. |