A Man’s World: Business, Art, and Religion

A Man’s World: Business, Art, and Religion

James LaVersa III

In the quarter century following the Civil War, fueled by technological advancements and westward expansion, America’s economy grew at the fastest rate in history. In this Gilded Age, American industrialists, exemplified by men such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and Cornelius Vanderbilt, amassed enormous fortunes. The average worker, although less dramatically, also saw real income rise. Social and cultural aspirations changed along with this increase in wealth. Gone were the pre-war days of financial modesty characteristic of the early nineteenth century. In Massachusetts, the number of estates valued at fifty thousand dollars or greater grew from thirty-six in 1829 to a staggering five hundred and nine, in 1891. Opulence became a central focus for American elites. Above all, refined taste in building, furnishings, and collecting art became prized demonstrations of social standing.

In the quarter century following the Civil War, fueled by technological advancements and westward expansion, America’s economy grew at the fastest rate in history. In this Gilded Age, American industrialists, exemplified by men such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and Cornelius Vanderbilt, amassed enormous fortunes. The average worker, although less dramatically, also saw real income rise. Social and cultural aspirations changed along with this increase in wealth. Gone were the pre-war days of financial modesty characteristic of the early nineteenth century. In Massachusetts, the number of estates valued at fifty thousand dollars or greater grew from thirty-six in 1829 to a staggering five hundred and nine, in 1891. Opulence became a central focus for American elites. Above all, refined taste in building, furnishings, and collecting art became prized demonstrations of social standing.

One of the best examples of the opulent construction of the time is the massive North Carolina estate, Biltmore. In 1889 George W. Vanderbilt (the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt) commissioned the collaborative work of Fredrick Law Olmsted (landscape architect) and Richard Morris Hunt (architect). In 1893 George’s older brother, Cornelius Vanderbilt II would also commission Hunt to build his Newport RI home, The Breakers. When it was completed in 1895, George’s “little mountain escape” totaled 187,926 square feet. Comprising 250 individual rooms, the building was decorated according to the French Chateau motif. Although the Vanderbilt family is more often associated with industrialization, George Vanderbilt and his wife Edith Dresser Vanderbilt exemplified the “progressive reform ideals” also characteristic of the period, attested by new ideas implemented in their farmland management on the vast country estate.

One of the best examples of the opulent construction of the time is the massive North Carolina estate, Biltmore. In 1889 George W. Vanderbilt (the grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt) commissioned the collaborative work of Fredrick Law Olmsted (landscape architect) and Richard Morris Hunt (architect). In 1893 George’s older brother, Cornelius Vanderbilt II would also commission Hunt to build his Newport RI home, The Breakers. When it was completed in 1895, George’s “little mountain escape” totaled 187,926 square feet. Comprising 250 individual rooms, the building was decorated according to the French Chateau motif. Although the Vanderbilt family is more often associated with industrialization, George Vanderbilt and his wife Edith Dresser Vanderbilt exemplified the “progressive reform ideals” also characteristic of the period, attested by new ideas implemented in their farmland management on the vast country estate.

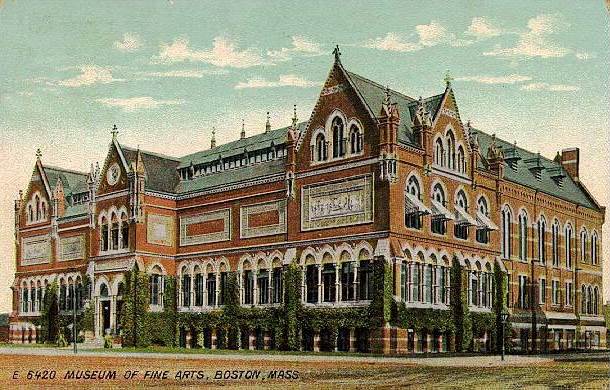

The Vanderbilt’s were not alone in these ideals. The men of the Gilded Age, including Martin Brimmer, Daniel Merriman and John Pierpont Morgan, demonstrate the elision of art, business and religion distinctive of the time. The importance of religion was noted by Siegfried Bing, visiting America in 1893 to survey for France the state of the arts at the World's Columbian Exposition: "In a country where everything constantly changes on the highway to the future . . . where no moment of rest, nor backwards glance, is allowed those who do not want to be left behind, religion is the only immutable element" (Artistic America, 70-71). It was expected that successful businessmen support the arts as a means of cultural and religious uplift. Prominent names are found among those building opulent estates, establishing museums, and being active members of their churches. As a direct result of the new wealth, Americans began to collect art in large quantities and public interest in art lead to the foundation of museums such as the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

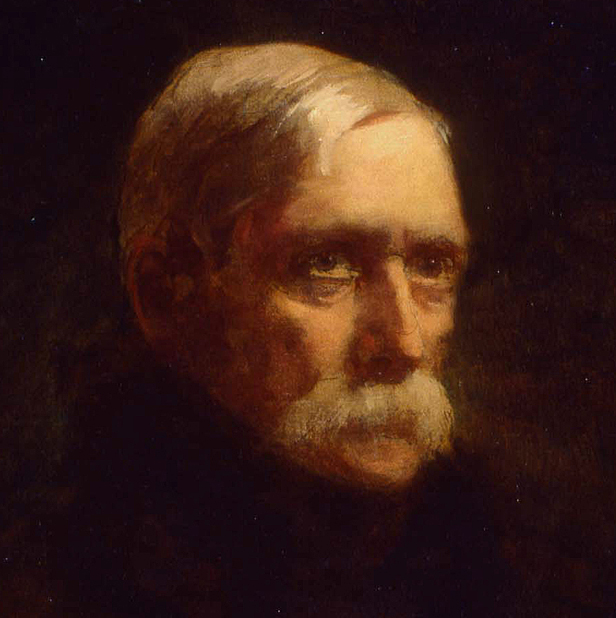

Boston experienced a great urban renewal during the post-civil war era. Massive reclamation of land by the filling-in of the Back Bay enabled an expansion of property for home, business, and culture. Boston did not have an art museum, and when the area of Copley Square was donated to the city it was no surprise that a museum of fine arts was to be built there. The museum welcomed the public from 1876 to 1909 at the south side of the square before moving to its present location on Boston’s Fenway. Martin Brimmer, a wealthy Bostonian and collector, was named the museum’s first director. Brimmer’s goal in appointing a diversified board was, in his words “to have many different interests represented and to have trustees whom we can turn to for various kinds of aid” (letter from Brimmer to Charles Eliot Norton, professor of the history of art at Harvard, Paris, December 3, 1882). The board was eventually composed of manufactures, bankers, archeologists, and educators; each providing a specific angle of leverage and expertise. Under his supervision, the original Boston Museum of Fine Arts was built by architects Sturgis and Brigham in the Ruskinian-Gothic style. Brimmer’s religious affiliation was similarly intense. He was a prominent member of Trinity Church, a commitment he shared with Sarah Wyman Whitman who painted his best-known portrait four years before his death.

Boston experienced a great urban renewal during the post-civil war era. Massive reclamation of land by the filling-in of the Back Bay enabled an expansion of property for home, business, and culture. Boston did not have an art museum, and when the area of Copley Square was donated to the city it was no surprise that a museum of fine arts was to be built there. The museum welcomed the public from 1876 to 1909 at the south side of the square before moving to its present location on Boston’s Fenway. Martin Brimmer, a wealthy Bostonian and collector, was named the museum’s first director. Brimmer’s goal in appointing a diversified board was, in his words “to have many different interests represented and to have trustees whom we can turn to for various kinds of aid” (letter from Brimmer to Charles Eliot Norton, professor of the history of art at Harvard, Paris, December 3, 1882). The board was eventually composed of manufactures, bankers, archeologists, and educators; each providing a specific angle of leverage and expertise. Under his supervision, the original Boston Museum of Fine Arts was built by architects Sturgis and Brigham in the Ruskinian-Gothic style. Brimmer’s religious affiliation was similarly intense. He was a prominent member of Trinity Church, a commitment he shared with Sarah Wyman Whitman who painted his best-known portrait four years before his death.

The great financer, J. Pierpont Morgan was similarly devoted to church and to cultural affairs. He served as a senior warden of St. George’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan, colloquially referred to as "Morgan's Church". St. George’s, whose present building was begun in 1846, was arguably the first important religious building to adopt the Romanesque Revival style in America. The same style was selected for Central Congregational in 1883. With Morgan’s support St. George’s abolished pew rentals and focused on social services to the surrounding neighborhood. Morgan also played a supportive role at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as trustee (1888–1904) and later as its president (1904–1913). Under his leadership the Museum launched an ambitious acquisition program. Morgan also collected illuminated books, Old Master drawings, and other historical manuscripts and books that now form the core of the present Morgan Library and Museum.

The great financer, J. Pierpont Morgan was similarly devoted to church and to cultural affairs. He served as a senior warden of St. George’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan, colloquially referred to as "Morgan's Church". St. George’s, whose present building was begun in 1846, was arguably the first important religious building to adopt the Romanesque Revival style in America. The same style was selected for Central Congregational in 1883. With Morgan’s support St. George’s abolished pew rentals and focused on social services to the surrounding neighborhood. Morgan also played a supportive role at the Metropolitan Museum of Art as trustee (1888–1904) and later as its president (1904–1913). Under his leadership the Museum launched an ambitious acquisition program. Morgan also collected illuminated books, Old Master drawings, and other historical manuscripts and books that now form the core of the present Morgan Library and Museum.

These early museums, lauded for bringing art to the public sphere, have been also criticized. The influential urban historian Lewis Mumford observed that these philanthropic enterprises could also be self-serving; “by patronage of the museums the ruling metropolitan oligarchy of financers and office holders established their own claims to culture: more than that they fixed their own standards of taste, morals and learning as that of their civilization” (The Culture of Cities, p 32). Regardless of the claims of the Mumford, men such as Morgan and Brimmer have greatly enriched American cultural resources.

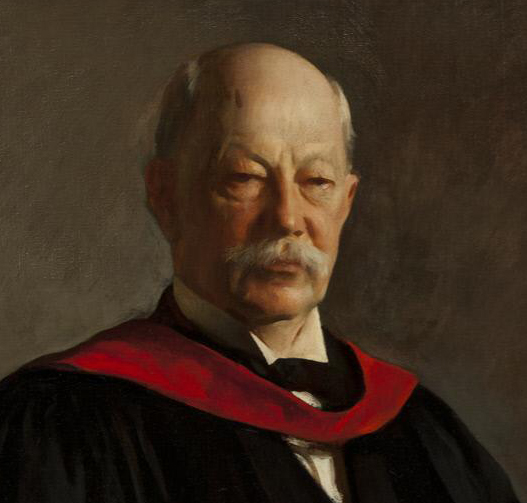

As the minister of Central Congregational Church in Worcester, Daniel Merriman was a man of great influence in the community. He was responsible for the 1885 building of the new Central Congregational Church in Worcester. Along with his wife Helen Bigelow Merriman, Rev. Merriman was one of the most significant supporters in the establishment of the Worcester Art museum. Rev. Merriman’s background in engineering and interest in architecture, coupled with Mrs. Merriman’s long connection to the visual arts, made him an ideal backer for a museum. Both Helen and Daniel were named original founders and trustees. Also, Daniel Merriman was named the Museum’s first president.

As the minister of Central Congregational Church in Worcester, Daniel Merriman was a man of great influence in the community. He was responsible for the 1885 building of the new Central Congregational Church in Worcester. Along with his wife Helen Bigelow Merriman, Rev. Merriman was one of the most significant supporters in the establishment of the Worcester Art museum. Rev. Merriman’s background in engineering and interest in architecture, coupled with Mrs. Merriman’s long connection to the visual arts, made him an ideal backer for a museum. Both Helen and Daniel were named original founders and trustees. Also, Daniel Merriman was named the Museum’s first president.

It is rare to see commitment to church, art, and business so visibly mingled today. Brimmer and Morgan differ from our contemporary examples of philanthropists. Entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates, for example, are more global and practical. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation sees a moral calling to support the disadvantaged, focusing on the issues of poverty, health, and education around the world. Brimmer, Morgan, and Merriman felt obligated as church-going men to bring the arts to the people through patronage and activism. Understanding the philanthropic landscape of the Gilded Age, makes Central Congregational Church’s importance in the era clear.

Further Reading:

Andrews, Wayne. “Martin Brimmer, The First Gentleman of Boston,” Archives of American Art Journal, 30, No 1/4 (1990): 4-7.

Bing, Samuel (Siegfied). La Culture artistique en Amerique (1885), trans. by Benita Eisler as "Artistic America," in Artistic America, Tiffany Glass and Art Nouveau (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press, 1970).

Mumford, Lewis. The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1938.

Tomkins, Calvin. Merchants and Masterpieces, The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1970.

Whitehill, Walter Muir. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: A Centennial History. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University, 1970.