Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock: Gothic Revival and the windows of the 1940s

Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock: Gothic Revival and the windows of the 1940s

Gothic Revival first appeared in the mid-19th century with architects such as Richard Upjohn,

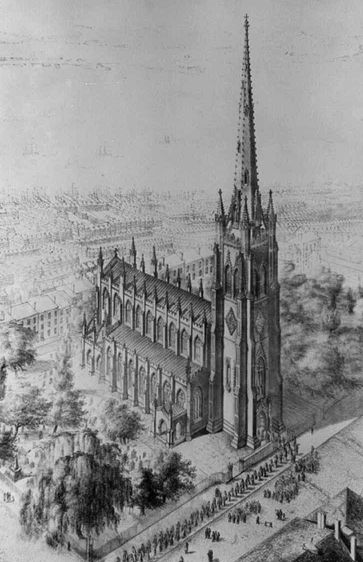

Gothic Revival first appeared in the mid-19th century with architects such as Richard Upjohn,  responsible for Trinity Church, Wall Street, NY of 1846. In Europe and the United States, parishioners saw the style of attenuated lines and pointed arches as bringing the stability of an age of faith to an era facing political and social change. In the 20th century, influenced by architects such as Ralph Adams Cram, the United States experienced a second Gothic Revival. Cram was the architect of Princeton University and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, both sites where Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock’s windows were installed.

responsible for Trinity Church, Wall Street, NY of 1846. In Europe and the United States, parishioners saw the style of attenuated lines and pointed arches as bringing the stability of an age of faith to an era facing political and social change. In the 20th century, influenced by architects such as Ralph Adams Cram, the United States experienced a second Gothic Revival. Cram was the architect of Princeton University and the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, both sites where Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock’s windows were installed.

Cram's writings and his supervision of decorative commissions expounded not only the religious issues, but also the idea of the purity of materials and the search for the so-called true principles of glass painting developed by the Arts and Crafts movement. He differed from proponents of the original Arts and Crafts movement in that he developed an extremely narrow definition of appropriate models and, in particular, the 13th-century French Gothic window as the primary source of inspiration.

The architect characterized opalescent windows as antithetical to a spiritual atmosphere and gave explicit directions to studios to avoid them. His disdain for opalescent glass appears associated with its ubiquity - from lampshades to row-house stairwells - from which Cram deduced its inappropriateness for a church. Cram's efforts began the 20th-century polarization that generally relegated the stained glass window in America to church decoration, a situation that lasted until the 1960's when a rebirth of stained glass became again linked to contemporaneous work in the fine arts. Cram was also explicit in his criticism of three-dimensional style windows of the type imported from Munich and Innsbruck for many Catholic churches. Writing for the journal Stained Glass in 1931, he stated that they were "too terrible to contemplate" and argued that it had become a question of "how to get rid of them without impiety. There was and is but one way. Go they must . . .” Cram called for replacement by windows of the same subject "but made by real artists," flattering the stained glass trade perhaps in an attempt to realize his agenda.

Cram was one of the founding members of the Medieval Academy of America. Given the importance of architects in the selection of stained glass studios, American studios quickly espoused the style until it became almost universal. Boston saw the rise of large and influential studios working in a  Gothic-Revival style, such as those of Wilbur Herbert Burnham and Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock (both with significant windows in the National Cathedral, Washington DC), George C. Ball, (St. Joseph Chapel, College of the Holy Cross), Earl Edward Sanborn (Bapst Library, Boston College ), Harry Wright Goodhue, and Margaret Redmond (Trinity Church, Boston). Charles J. Connick however, was the movement's chief polemicist, and possibly its most prolific studio. Joseph G. Reynolds worked with Charles Connick before founding the firm in Boston in 1923.

Gothic-Revival style, such as those of Wilbur Herbert Burnham and Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock (both with significant windows in the National Cathedral, Washington DC), George C. Ball, (St. Joseph Chapel, College of the Holy Cross), Earl Edward Sanborn (Bapst Library, Boston College ), Harry Wright Goodhue, and Margaret Redmond (Trinity Church, Boston). Charles J. Connick however, was the movement's chief polemicist, and possibly its most prolific studio. Joseph G. Reynolds worked with Charles Connick before founding the firm in Boston in 1923.

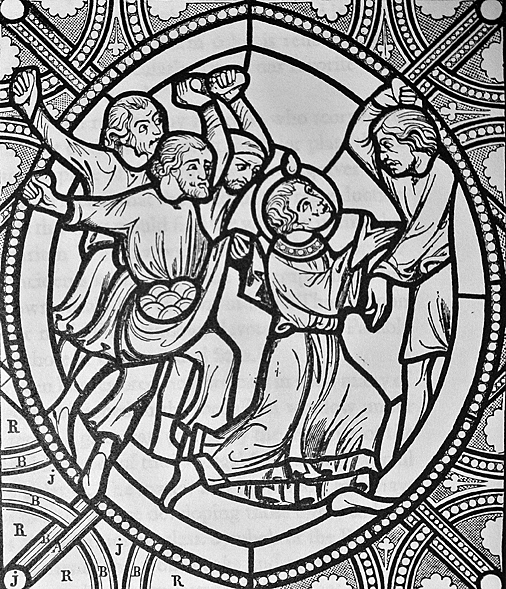

Carefully crafted windows that closely emulated medieval precedents were possible because the American Gothic-Revival studios, like their European predecessors, could rely on publications by restorers of stained glass. Many restorers published books with lavish reproductions and tracings or other detailed restoration drawings. N. J. H. Westlake's History of Design in Stained Glass, 1891–1894, for instance, was an essential reference for American studios. Translations of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc's section on stained glass from his Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture, 1854-68 were also available. Indeed, many of the illustrations that Connick used for his own work, Adventures in Light and Color, 1937, were borrowed from the books of Westlake and Violet-le-Duc. See the image of the Stoning of Stephen, after Violet-Le-Duc, to the upper left. Like the works of Westlake and Violet-le-Duc, Hugh Arnold and Lawrence Saint's Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France, 1913, was cherished by glass studios for its clear overview of what had become the canon of great medieval windows: Le Mans, Poitiers, Canterbury, Chartres, York, through Rouen and Fairford of the 15th century.

Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock produced windows for the 1931 Shove Memorial Chapel for Colorado College portraying early English saints after tracings taken from the 12th-century windows of the cathedral of Le Mans, France. Eugène Hucher, who headed a large studio that later exported glass to the United States, had restored the glass and published the tracings made from the windows (Calques des vitraux peints de la cathédrale du Mans, 2 vols. Paris, 1864). Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock believed that the Le Mans models were an appropriate complement to the Norman Romanesque architecture of the chapel. (Timothy Fuller, ed., This Glorious and Transcendant Place (Colorado Springs, 1981).

Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock produced windows for the 1931 Shove Memorial Chapel for Colorado College portraying early English saints after tracings taken from the 12th-century windows of the cathedral of Le Mans, France. Eugène Hucher, who headed a large studio that later exported glass to the United States, had restored the glass and published the tracings made from the windows (Calques des vitraux peints de la cathédrale du Mans, 2 vols. Paris, 1864). Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock believed that the Le Mans models were an appropriate complement to the Norman Romanesque architecture of the chapel. (Timothy Fuller, ed., This Glorious and Transcendant Place (Colorado Springs, 1981).

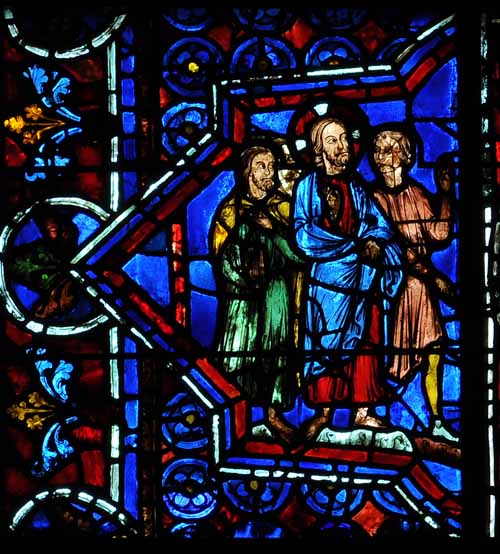

The imagery selected by the Second Gothic Revival contrasts markedly with that of the 19th-century, whether traditional European or American opalescent. A detail of Christ and companions from an ambulatory window from Chartres Cathedral (Bay 30), above, dated about 1215-20 demonstrates the Gothic design of small medallions set against mosaic grounds. Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock reproduced the same insistent blue and red contrast and silhouetting of figures against a plain, undifferentiated background. The alternation of figural medallion and decorative border repeats the even balance of the medieval relationship.

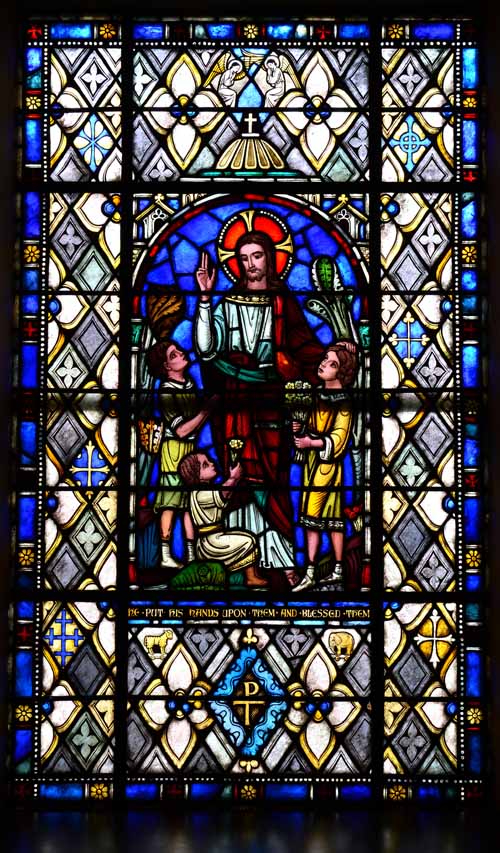

Several important windows by the firm grace the landmark building of Arlington Street Church, Boston (whose Tiffany program extended from 1898 through 1929). Gothic Revival was favored for newer work and in 1924 and 1927 Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock installed windows in the Sunday School Room (now the Hunnewell Chapel). The image of Christ Blessing the Children of 1924 shows the same cartoon that was used for Central Congregational.

The Gothic-Revival windows in Central Congregational church were installed beginning in 1946. Three windows above the cancel present Christ flanked by saints Peter and Paul. The great exterior wall has three tall lancets. That on the left begins at the top with the Greek letter Alpha (for the beginning), and in descending order, a purse with coins followed by the Parable of the Pharisee and the Tax Collector (Luke 18), a burning lamp labeled fides (faith), Wise Virgins with lighted lamps (Matthew 25), followed by pigs and the Prodigal Son (Luke 15). In the center lancet, the Dove of the Holy Spirit hovers over Christ in majesty, followed by birds of the air above the Parable of the Sower (Matthew 13), then sheep and Christ as the Good Shepherd (John 10). On the right the window begins with the  sign of the Omega (for the end), a soul in purgatory and Lazarus at the Rich Man’s feast (Luke 16), the true Vine (vitis vera) above laborers in the vineyard (Matthew 20), and a donkey above the Good Samaritan (Luke 10). Above, in the rose, the Lamb of God is surrounded by angels playing musical instruments. To the side are the Nativity and Christ and the Children, set in grisaille lattice frames. In the entrance way is the Visitation (Ruth Loring Dodd memorial).

sign of the Omega (for the end), a soul in purgatory and Lazarus at the Rich Man’s feast (Luke 16), the true Vine (vitis vera) above laborers in the vineyard (Matthew 20), and a donkey above the Good Samaritan (Luke 10). Above, in the rose, the Lamb of God is surrounded by angels playing musical instruments. To the side are the Nativity and Christ and the Children, set in grisaille lattice frames. In the entrance way is the Visitation (Ruth Loring Dodd memorial).

The studio produced a publication about its work: Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock: Stained Glass Windows Designed and Made in their Studio, One Washington Street, Boston, Massachusetts, Boston, 194??

The studio produced a publication about its work: Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock: Stained Glass Windows Designed and Made in their Studio, One Washington Street, Boston, Massachusetts, Boston, 194??

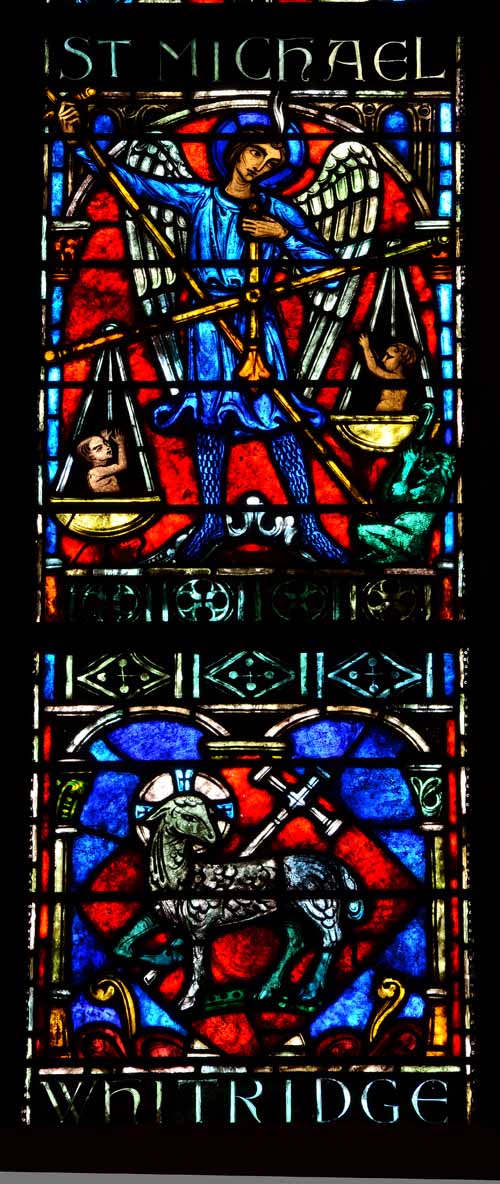

Slightly before Central Congregational’s windows, 1943-44, St. Bartholomew’s Church (Park Avenue and 51st street NYC) commissioned the firm for its great south rose window of Apostles and Saints and for windows in the children’s chapel of the sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, and Marriage (Becca Earley Richards, Holy Light, The Iconography and History of the Stained Glass of St. Bartholomew’s Church in New York City (New York, 2007). The firm also produced two massive windows for Princeton University Chapel. Multi-light windows celebrating martyrs (north transept) and teachers (south transept) grace the Cram-designed building. The archangel Michael weighs the souls. See a recent video: Richard Stillwell, The Chapel of Princeton University, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971.

Other commissions include:

American Church in Paris (designed by Cram)

Second Congregational Church, West Newton: Chancel and South Transept

First Congregational Church, Winchester: Auditorium and Ripley Chapel.

Church of St. John the Evangelist, Hingham: 3 windows.

Church of Catherine of Siena, Norwood: 4 windows

Wellesley College Chapel: many windows, dating from 1925 onwards

Cathedral of St. John the Divine NYC: nave aisle window on Medical theme

First Presbyterian Church, NYC: Te Deum and aisle windows.

Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church, Pittsburgh: clerestory windows

East Liberty Presbyterian Church, Pittsburgh: window over entrance

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Winston-Salem NC: nave windows

Shove Memorial Chapel, Colorado College, Colorado Springs CO: all windows. 1931