Animals of Tibetan Nomads

From The Conservancy for Tibetan Art and Culture

http://www.tibetanculture.org/index.htm

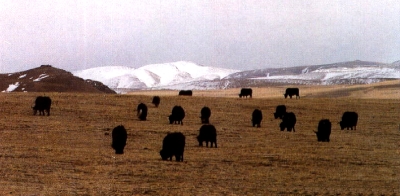

Tibetan nomads raise yaks, yak-cattle hybrids (dzo), sheep, goats, and horses. The rugged land and harsh climate of the Himalayas and Tibetan rangeland require the seasonal movement of these animals between lowland and upland pastures. This pastoral cycle continues today with the movement of millions of animals. These animals provide milk and milk products, meat, hair and wool, and hides for the nomads' basic existence. Yaks are unique to the Tibetan region and make life possible for people across much of Tibet. Their domestication perhaps 4,000 years ago enabled nomads to populate the Tibetan steppe. These animals can withstand colder temperatures than horses and can travel across rough terrain easily. Yaks have been crossbred with cattle so that they will produce more milk and calves. Yaks' long, coarse hair is woven into strong nomadic tents that keep out the rain and fierce winds, yet let light in. Tibetans place so much value on the yak that the Tibetan term for yaks, nor, can be translated as "wealth." Yaks are trained to the saddle and are used as pack animals and mounts. Some yaks are now raised in the western United States.

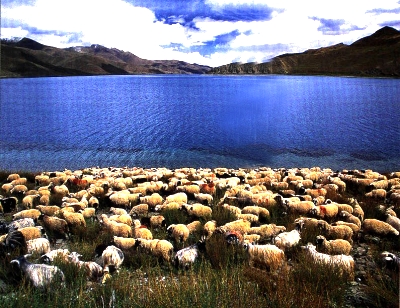

Sheep provide greater income for nomads than yaks due to the value of their wool. Nomads eat their meat and trade it to settled farmers. Tibetan sheep wool ranks among the highest in quality for carpet production due to its elasticity and deep luster. Tibetan goats are raised primarily in western Tibet. Nomads barter the goats' milk and meat for staples. These animals also produce the fine cashmere wool famous for centuries in shawl production. "Cashmere" got its name from the region of Kashmir presently in India and Pakistan, where the fabric was traded. The reputation of this wool remains strong today through the production of pashmina shawls, a product of the finest goat wool. The controversial shatoosh shawls, appropriately banned in India and the West, are made from the neck hair of the endangered wild Tibetan antelope.