Fireplaces in Central Congregational

Fireplaces in Central Congregational

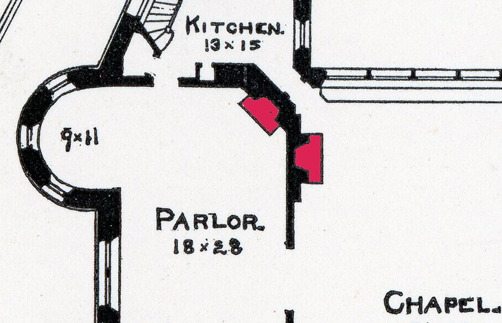

Sarah Wyman Whitman’s commission for decorative artwork at Central Congregational Church included two fireplaces that she designed. Both were made out of terra cotta, a type of claybody that when hard fired becomes able to withstand weather. In the 1880's and 1890's the material grew in popularity, especially for three-dimensional ornamentation on building facades. Like her glass, the fireplaces were most likely executed in collaboration with other craftspeople, with stunning results. They share a wall and a chimney, although one faces the former chapeland the other the parlor. While both fireplaces represent the clean style and honest materials characteristic of the Arts and Crafts concepts that Whitman espoused, they differ greatly in design and subject matter.

Sarah Wyman Whitman’s commission for decorative artwork at Central Congregational Church included two fireplaces that she designed. Both were made out of terra cotta, a type of claybody that when hard fired becomes able to withstand weather. In the 1880's and 1890's the material grew in popularity, especially for three-dimensional ornamentation on building facades. Like her glass, the fireplaces were most likely executed in collaboration with other craftspeople, with stunning results. They share a wall and a chimney, although one faces the former chapeland the other the parlor. While both fireplaces represent the clean style and honest materials characteristic of the Arts and Crafts concepts that Whitman espoused, they differ greatly in design and subject matter.

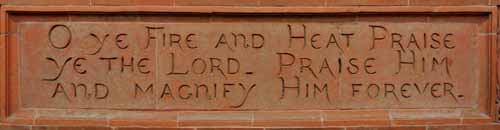

When built, the fireplace in the large meeting room adjacent to the former sanctuary, labeled “chapel” in the 1884 plans, was bold in its simplicity. Since then, the tapering russet brick over-mantel has been painted in the light color of the walls, so that the terra cotta mantelpiece appears to be a separate unit, lacking the dramatic floor to ceiling impact of the commanding original design. The remaining terra cotta fireplace stresses geometric forms with clean, spare lines. The arch opening for the hearth is a great half-circle framed with bricks in a radial pattern. The base of the chimney now appears to rest on a mantel supported by substantial dentil blocks. Between the hearth and the mantel is a horizontal decorative band that is anchored at each side by a decorative boss in an abstract design of swirling acanthus leaves.

The frieze has incised text incorporating the lines naming God’s creation of heat and fire from the “Benedicite, omnia opera domini,” also known as the Song of Creation. This text, of course, addresses the function of the fireplace: “O ye Fire and Heat Praise ye the Lord. Praise Him and Magnify Him forever. ” (Daniel 3:66).The verses were ascribed to the Three Hebrews who had been cast into a fiery furnace by King Nebuchadnezzar after they refused to worship his golden statue. Manifesting God’s power over all creation, they emerged from the furnace miraculously untouched. This canticle might be said or sung as part of Christian worship in both Protestant and Roman Catholic traditions. Whitman inscribed these lines in her signature script also found on her book bindings and stained glass windows.

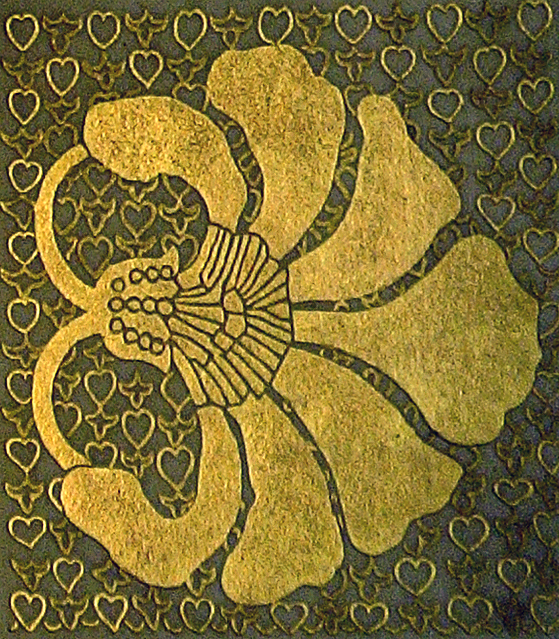

The front parlor fireplace is on a more domestic scale, although a comparison between the historical photograph and the current fireplace indicates that the overmantel with mirrors is no longer in place and the wooden mantel is now painted white. Decoratively, it contrasts with the austerely ornamented chapel fireplace with its text anchored by its two blocks with motifs drawn from nature as its focal point. The parlor mantel is supported by a lighter wooden dentil molding atop a band with a sawtooth design. The terra cotta fireplace is  surroundedby a lively tapestry of natural scenes. Oncloserinspection of the upper corners are a sun (right) andmoon (left), less prominently sculpted than the leaves and partially hidden by them. On theright, Whitman depicts an American native pinespeci

surroundedby a lively tapestry of natural scenes. Oncloserinspection of the upper corners are a sun (right) andmoon (left), less prominently sculpted than the leaves and partially hidden by them. On theright, Whitman depicts an American native pinespeci es,the eastern white pine: found in all the New England states. Viewed at close range, the needles look thick and their clustering is exaggerated. At a distance of ten feet, however, the branches and needles look natural and brush-like. A pair ofdozing northern saw-whet owls are perched among the pine’s needles. While the tree on the right-hand side is an evergreen; the left is dominated by leaves of the deciduous horse-chestnut tree. This native of the Balkan forest was introduced to the colonies and may be seen in Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut and Vermont. The owl, very probably a great horned owl, in the chestnut tree has caught a sparrow and clutches the limp creature in his claws, a surprising note that addresses the harsh reality of nature. This nature imagery suggests Whitman’s paintings, not her book designs. Whitman’s interest in these s

es,the eastern white pine: found in all the New England states. Viewed at close range, the needles look thick and their clustering is exaggerated. At a distance of ten feet, however, the branches and needles look natural and brush-like. A pair ofdozing northern saw-whet owls are perched among the pine’s needles. While the tree on the right-hand side is an evergreen; the left is dominated by leaves of the deciduous horse-chestnut tree. This native of the Balkan forest was introduced to the colonies and may be seen in Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut and Vermont. The owl, very probably a great horned owl, in the chestnut tree has caught a sparrow and clutches the limp creature in his claws, a surprising note that addresses the harsh reality of nature. This nature imagery suggests Whitman’s paintings, not her book designs. Whitman’s interest in these s ubjects can be seen in the painting Chestnut in Bloom/A Diptych which greatly resembles the forms on theparlor fireplace (attributed to Sarah Wyman Whitman, formerly owned by Samuel E.Codman, Charles G. Loring

ubjects can be seen in the painting Chestnut in Bloom/A Diptych which greatly resembles the forms on theparlor fireplace (attributed to Sarah Wyman Whitman, formerly owned by Samuel E.Codman, Charles G. Loring House, Prides Crossing, Massachusetts sold at Skinner’s sale of American and European Paintings, May 15, 2009 Lot No. 135).

House, Prides Crossing, Massachusetts sold at Skinner’s sale of American and European Paintings, May 15, 2009 Lot No. 135).

Nancy Jones, an expert on the Boston Terra Cotta Company, which was founded in 1880, suggested a possible scenario for the implementation  of aWhitman design. The Company was located at 394 Federal Street where the sculptor Truman H.Bartlett also had a studio. Bartlett had established a school for sculpture and modeling in 1879, where women received instruction, including the decoration of vases. (The Mugar Library, Boston University holds Bartlett’s papers.) Other artisans, including Boston glass painter Arthur B. Cutter, and Ira Conklin of A. Hall Terra Cotta Company of Perth Amboy studied there. Since the Boston City Directory recorded the studio operative at that location until at least 1887, perhaps Whitman consulted with Bartlett. She might have commissioned him to take her designs and create the molds for the castings that would then be executed by the Boston Terra Cotta Company. Both designs appear unique to Central Congregational. Susan Tunick, author of Terra-Cotta Skyline: New York's Architectural Ornament (Princeton Architectural Press, 1997) has communicated that the design was not an offering of any of the firms that she researched.

of aWhitman design. The Company was located at 394 Federal Street where the sculptor Truman H.Bartlett also had a studio. Bartlett had established a school for sculpture and modeling in 1879, where women received instruction, including the decoration of vases. (The Mugar Library, Boston University holds Bartlett’s papers.) Other artisans, including Boston glass painter Arthur B. Cutter, and Ira Conklin of A. Hall Terra Cotta Company of Perth Amboy studied there. Since the Boston City Directory recorded the studio operative at that location until at least 1887, perhaps Whitman consulted with Bartlett. She might have commissioned him to take her designs and create the molds for the castings that would then be executed by the Boston Terra Cotta Company. Both designs appear unique to Central Congregational. Susan Tunick, author of Terra-Cotta Skyline: New York's Architectural Ornament (Princeton Architectural Press, 1997) has communicated that the design was not an offering of any of the firms that she researched.