Patrick C. Keely, Cathedral of the

Holy Cross, 1866-1875, Boston.

Photo: Michel M. RaguinIt is important to state immediately; this is not a book about artists. These essays

Louis L. Long, St. Alphonsus’

Church, architecture 1855-1857,

windows Mayer and Co.,1890s,

New Orleans.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin often include biographical information thanks to the research of many scholars on the careers of the fascinating individuals in this field. Much more should be encouraged. This text, however, addresses the historical, political, religious, and social systems that nourish the individual artists’ work. In this introduction, I hope to explain some of the concepts behind this study.

Embellishment of public spaces via the translucent image effects both community and individual. Thus we are looking at an art deeply dependent on public support for its very existence. The impact of the leaded and painted window is linked to its structure; materials and craftsmanship condition even the simplest production. Set within domestic and public buildings, window proclaims the intellectual and spiritual values of the makers. Unlike our museum experience, where, invariably, we are confronted by art stripped of its context, most windows still live within their original settings. They dialogue with the architecture and imagery of the site. To understand the subject matter we see, we are challenged to examine the priorities of those who commissioned the work. Each installation extends far beyond the artists and studios themselves.

Architectural context

Stained glass was important in the Middle Ages because of its close association with religious architecture. Allied to the art of the Gothic construction, the figural window dominated image making for four centuries, emerging again in the 19th century with the revival of the Gothic building. Contemporary designers, however, of distinctly non-historic expression now look to these great ensembles as moments when image, space, color, light and materials fused in visual concord. Stained glass is always engaged with architecture, through an intimacy with the architectural plan at the origin of the building or intervening to restructure existing space into a new, expressive environment. Even the exterior of a building, as exemplified by apse of Bourges cathedral, creates a rich interplay of shapes and textures. Windows were made for architecture and architecture was made for windows.

Placement within buildings and the audience: Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral, England,

Trinity Chapel, north side, widows

n.III, n.IV, and n.V showing Becket

Miracle windows, 1185-1215.

Photo: authorIt is on the interior, however, that light, color, and space truly reciprocate. Visitors are

Canterbury Cathedral, England,

Trinity Chapel, north side, widows

n.II through n.VII showing Becket

Miracle windows, 1185-1215.

Photo: author literally enveloped by glass at Canterbury Cathedral. The windows of the Trinity Chapel, to the east of the choir, depict the miracles St. Thomas Becket. Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, had been murdered in 1170 by emissaries of Henry II in a dispute over clerical privilege. Canonized two years after his death, Becket was soon recorded as a miracle worker, many interventions associated with visits to his tomb. The windows installed 1185–1207 and 1213/15-20 promulgated his cult, a tradition that formed the basis for Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. His tomb, now destroyed, was a raised monument in the center of the Trinity Chapel. The metal shrine was embellished with enamel colors and jewels; the windows with multihued glass. Flanked by windows and shrine, pilgrims circumnavigated a multi-sensory environment that proclaimed Becket's exemplary life and his power. The windows are an arresting display, a seemingly endless reiteration of the power of the martyr to intercede for his petitioners. The sheer brilliance of the multiple patterns - angular petals radiating from squares, circles divided in quadrants, canted squares and half circles, fan shaped successions, quatrefoils within circles, alterations of circles and diamonds - reinforce the multiplicity of cures. Just a preachers developed sermons for specific purposes for an audience of laity, it is probable that the monks who led the pilgrims around the Trinity Chapel explained the individual miracles.

Collaborative work

Bourges Cathedral, exterior from

east, about 1210-1215.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Works in stained glass at any date were, and still are, rarely signed. Even if they receive the name of the studio that produced them, windows develop in a series of stages, most frequently with specialists for each intervention. From the selection of the subject, to the sketched concept, to the full size drawing, to cutting each segment of glass, to the painting and firing of the glass, and to its assembly with lead and iron matrices, windows have historically been collaborative endeavors. These concepts of collaboration are remerging as vital aspects of many examples of contemporary art.

John La Farge at Judson Memorial Church

Collaboration is exemplified by the deeply admired work of John La Farge. One of his

Stanford White, Judson

Memorial Church, Washington

Square, New York, view from

east, 1888-93. Photo:

cbrowder.blogspot.comlast projects was the glazing for Judson Memorial Church, Washington Square, New York City, built between 1888 and 1893. The windows were planned by La Farge but installed over time.1 La Farge, as common to his method of working, was keenly attuned to the spatial and decorative structure designed by the architect Stanford White of the firm of McKim Mead and White. 2 Classicizing forms appear in the Beaux-Arts moldings, cornices, and rounded arches; the design of the glass window continued the same forms as the architecture.

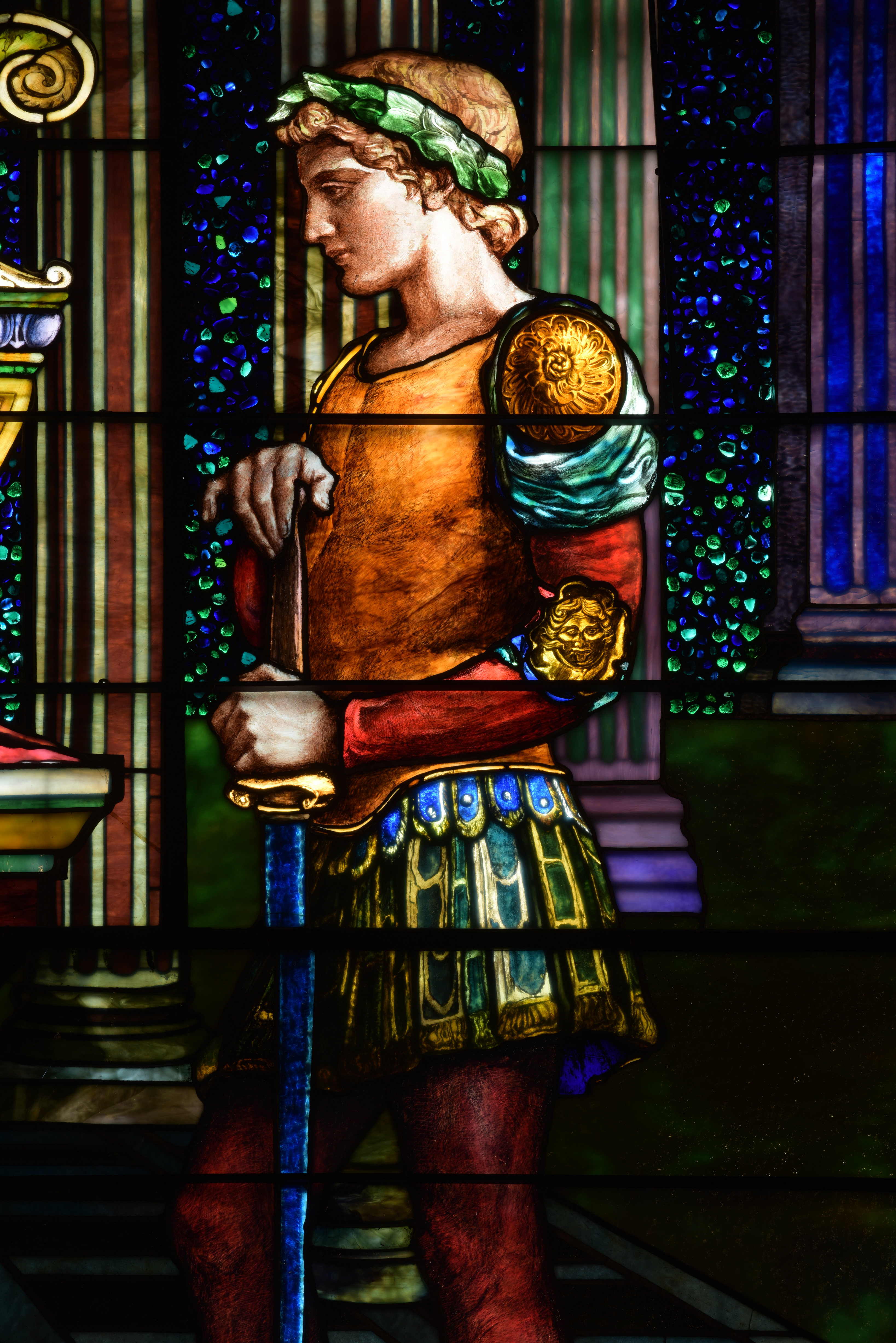

John La Farge, St.

George, Memorial to

Georgina van Aikan,

(executed after La Farge’s

death by his collaborator,

Thomas Wright), East 6,

Judson Memorial Church,

New York, 1915.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin

John La Farge, Sanctuary windows,

Judson Memorial Church, New York,

1899-1915. Photo: Michel M. Raguin The last window to be installed, showing St. George, a memorial to Georgina van Aikan, was executed by his collaborator, Thomas Wright five years after La Farge’s death. Wright based the St. George on the youthful warrior personifying “riches and honor” from the window Wisdom Enthroned, a memorial to Oakes Ames, from Unity Church, North Easton, Massachusetts completed in 1901. The New York commission was installed in 1915; the image reversed and fabricated with less painterly execution. The North Easton figure, discussed in the essay on Memorials in a Modern World, is lavishly modulated not only by the tone of the glass but

John La Farge, Riches

and Honor, detail, 1901,

Memorial to Oaks Ames,

Unity Church, North

Easton, Massachusetts.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin through surface paint, a clear demonstration that La Farge continually experimented with painted surfaces as well as opalescent layering. Contours are achieved with a smear shading of several values applied with visibly diverse brushstrokes. The surface is then enlivened with extremely thin scratches lifting off the wash. The young man’s red leggings appear to be solid pieces of red glass that are deeply worked through application and removal of paint to contour the legs. St. George at Judson Memorial church, in contrast, displays paint almost exclusively on the flesh areas. The torso is plated with several layers of glass, with the surface plate over variegated colors that suggest three dimensions; the leggings are construction of many pieces of opalescent glass. A sketch for St. George includes the full window with its architectural frame.3 This concept reiterates a constant of leaded and painted windows. They are part of an architectural setting.4

La Farge’s multiple sources

John La Farge, Sanctuary windows,

west side Judson Memorial Church,

New York, 1899-1910.

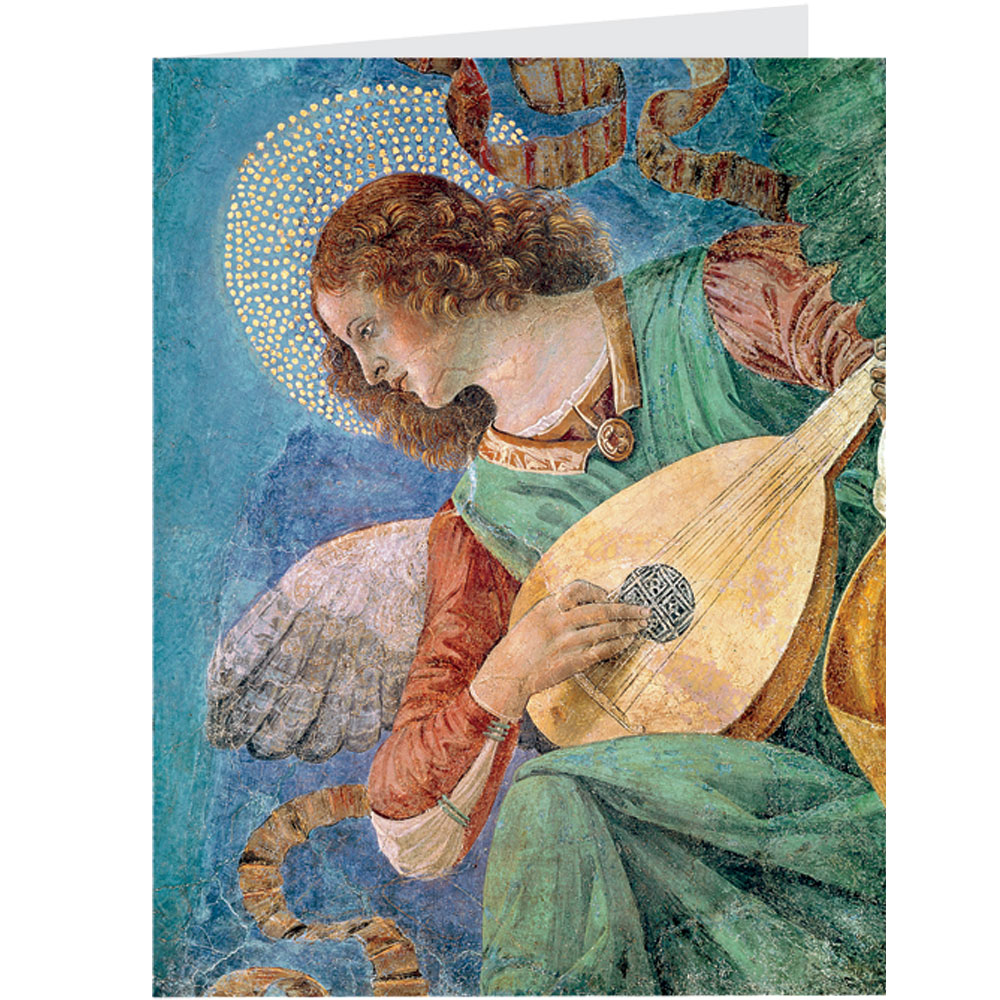

Photo: Michel M. Raguin The series of round windows on the west side of Judson Church are based on Renaissance precedents. Most striking may be La Farge’s replication of the well-known fresco by Melozzo da Forli of an Angel with a Lute.5 The painting is found in the Vatican libraries and was a widely distributed image in the 19th century. The technique of fresco, where the paint is applied in the space of a day, prioritizes linear contrast and flat, mural concepts. The blended tones in the opalescent glass produce a softer image. Both fresco and window, however, demonstrate the excitement of line defining space. At precisely the same time, the

Tyrolese Art Glass

Company, Innsbruck,

Angel and Lute,

1894, St. Joseph’s

Cathedral,

Manchester,

New Hampshire.

Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

John La Farge, Angel and Lute,

West 2, Judson Memorial Church,

New York, 1900-1904.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Tyrolese Art Glass Company, Innsbruck, Austria, had been commissioned to provide windows for St. Joseph’s Cathedral, Manchester, New Hampshire. An image of an Angel and Lute was installed in 1894. Both La Farge’s and the Austrian window exemplify a deep command of the materials of glass, but differently. La Farge striving for the blending of colors from the inspiration of oil painting and the Austrian designer still operating out

Melozzo da Forli, Angel and

Lute, 1477, Vatican Library,

Rome. Photo: courtesy trips

vatican-museums.com of the late-medieval alliance of stained glass and the graphic arts. The angel in Manchester show the clarity of contour and the use of cross hatching in shading that is familiar from the stained glass and drawings of the German Renaissance. 6 The use of common sources in much 19th century monumental imagery did not impede the expression of style of each glass painter.

Common models appreciated by artists throughout history

John La Farge had earlier designed a stained glass window after Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (1534-38) and other Venetian masters, explored in the essay on “Boston.” There was ample precedent for such borrowings and references to previous art. Our present language unthinkingly prioritizes art as avant-garde, original, personally expressive, and independent of public taste (hard earned through struggle against an uncomprehending public). Art of traditional societies, as the 19th century remained in many ways, more commonly sought art that valued skill, embodiment of public belief, and that was commissioned – or anticipated - for significant public display. These criteria predisposed the artist to demonstrate acquaintance with tradition, the study of Old Masters, and apprenticeship in the craft. Dissemination of recognizable subject matter, often through the medium of the print, supported references to Renaissance prototypes such as Melazzo da Forli and Titian, or 19th century masters such as Hans Hoffman or Bernard Plockhorst, a theme explored in the essay on Patronage: the American Museum and the American Church.

The competitive and successful artist was adamantly of his time and able to “read” the prevailing taste. Almost four centuries earlier, we find the same acumen in the stained glass produced by the Le Prince family of Normandy, a highly successful and innovative group of artists of the early 16th century.7

Renaissance Rouen

Engrand and Jean Le Prince,

Triumph of the Virgin, 1525, upper

two tiers, Church of Sainte-Jeanne

d’Arc (formerly St. Vincent), Rouen,

France. Photo: Michel M. Raguin

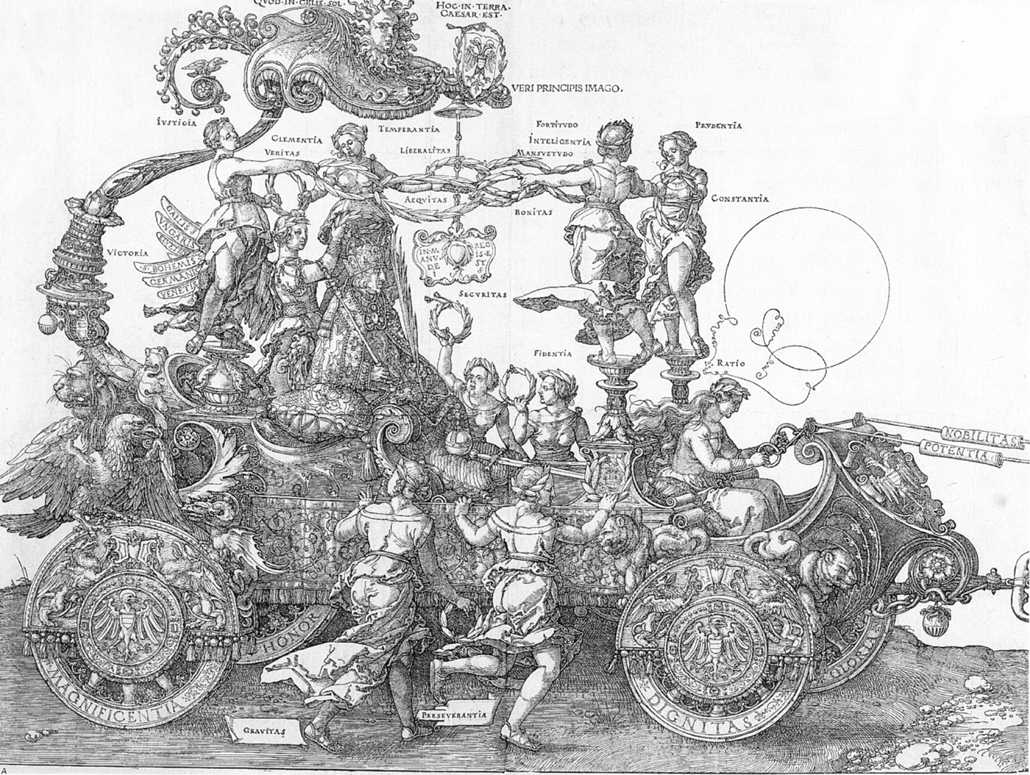

Albrecht Dürer, The Great

Triumphal Chariot of the Emperor

Maximilian I, detail, 1518, published

1522. Photo: Web Gallery of Art In 1525 Engrand and Jean Le Prince produced a series ofwindows for the church of St. Vincent, among them the Triumph of the Virgin.8 Spread out over three tiers and crowned by complex fenestration, the window plays off the concept of the civic “triumph.” At the time, rulers routinely engineered elaborate parades, or triumphal entries to mark auspicious occasions. In 1518 Albrecht

Engrand and Jean

Le Prince, Triumph of

the Virgin, detail of

Adam and Eve before

the cathedral of

Beauvais, 1525,

Church of

Sainte-Jeanne

d’Arc

(formerly St. Vincent),

Rouen, France.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin Dürer had finished the commission for the Holy Roman Emperor,The Great Triumphal Chariot of the Emperor Maximilian I. Publication of the woodcut waited until 1522, and caused an immediate sensation. The Le Prince family seized on the reference to construct a visually and intellectually brilliant song of praise to the Virgin. The citizen of Beauvais, their massive cathedral in the background are part of an elaborate pageant from the creation of the world, the fall of man though the seven deadly sins, and the power of the Virgin and her divine son to crush the servants of evil.

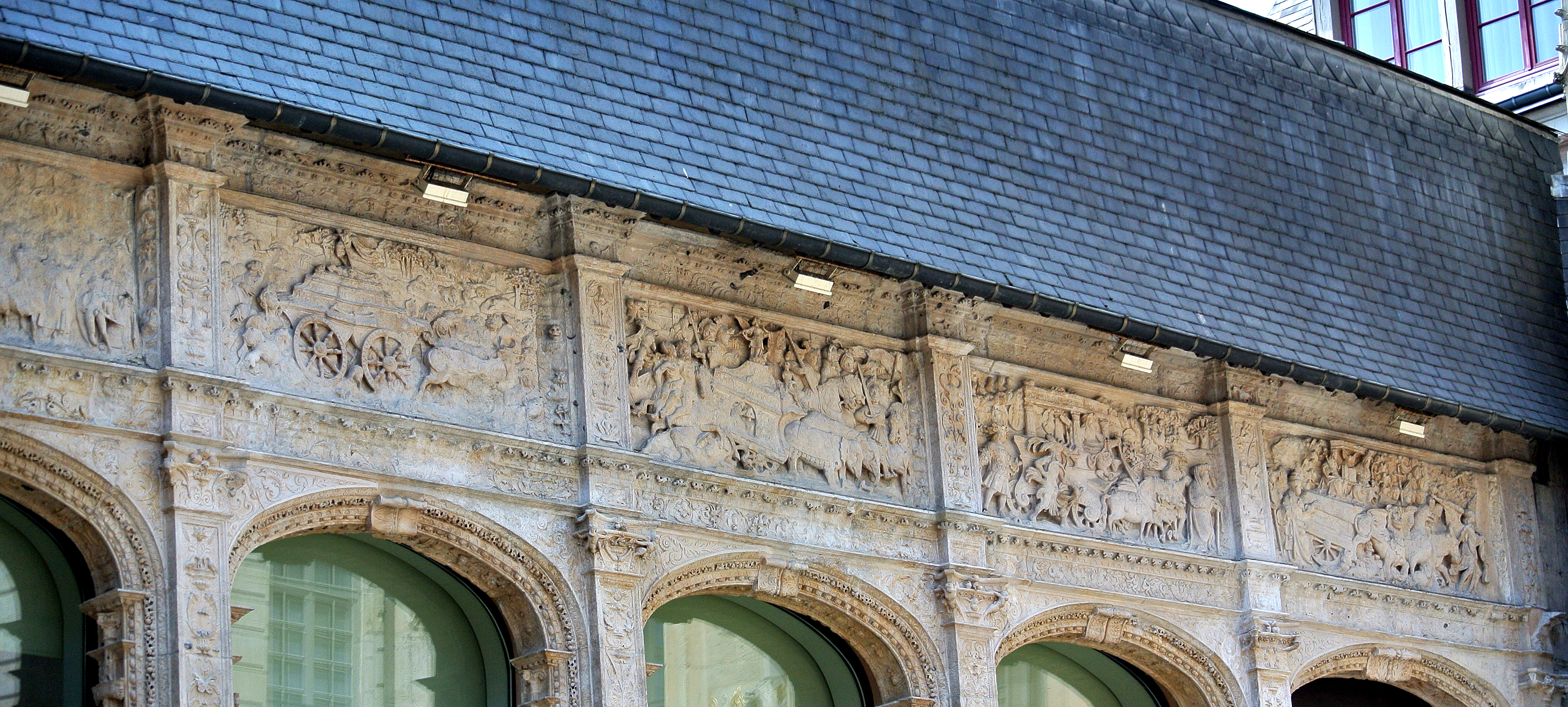

Triumphs of Petrarch, reliefs, beginning of

the 16th century, Hôtel de Bourgtheroulde,

Rouen, France. Photo: author At the same general era in Rouen, a lavish town house known as the Hôtel de Bourgtheroulde was being constructed.9 Its courtyard façade carried reliefs based on the Triumphs of Petrarch, a 14th-century Italian poet who had become required reading for the elite in Renaissance France. The 16th-century French sculptor focused on a sequence of carts accompanied by allegorical figures. The artists of windows, Engrand and Jean Le Prince, were clearly addressing a similar audience and speaking a similar language. They designed in the progressive Renaissance style of three-dimensional modelling and site-specific backgrounds. The contemporary taste for civic display and classical references were incorporated into their work.

Nineteenth-century England and Rubens

George Steuart, St. Chad’s Church,

1790-1792, Shrewsbury, England. The motivation for the transfer of the image was not the lack of ideas, but rather the .jpg)

George Steuart, St. Chad’s Church,

interior,1790-1792, Shrewsbury,

England. Photo: Michel M. Raguin search for a universal iconography shared by patron, artist, and community. The process crossed national boundaries and even religious divisions. The church of St. Chad’s in Shrewsbury, England typifies the “long 19th century’s” process of renewal and adaptation of the past. St. Chad’s had served a thriving community and a relative large stone church occupied the site since the 13th century. After the collapse of its tower in 1788 the church, by then a Church of England institution, was rebuilt in the Georgian style current for its time. The circular gallery was achieved through slender cast-iron columns, an innovation pioneered by England’s industrial revolution. A white interior, ceiling and cornice moldings with naturalistic foliage, and Corinthian columns terminating in capitals in gold, were current in this era that remained deeply attached to the classicism of Christopher Wren (1632 –1723).

Windows and paintings

.jpg)

David Evans, Descent

from the Cross, after Peter

Paul Rubens, St. Chad’s

Church, Shrewsbury,

England. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin

Peter Paul Rubens, Visitation,

Descent from the Cross, and

Presentation in Temple, 1612-14,

Cathedral of Our Lady, Antwerp.

Photo: courtesy Web Gallery of Art Originally glazed with simple clear quarry glass, the church

David Evans, Visitation,

Descent from the Cross, and

Presentation in Temple, after

Peter Paul Rubens, St. Chad’s

Church, Shrewsbury, England.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin received several leaded and painted windows in the 1840s by David Evans, a local stained glass painter.10 A three-part window over the altar reproduces Rubens’ great triptych of 1612-14 in the Roman Catholic cathedral of Antwerp showing the Descent from the Cross flanked by the Visitation and Presentation. Evans clearly made every effort to create an accurate representation of the famous work in glass, keeping the same color selections for the garments and endeavoring with vitreous paint to approximate the modulation of tone achieved in oil. He uses tradition pot-metal glass, colored in the mass, augmented by silver stain, prominent in the women’s blond hair. There looks to be light-blue flashed glass in the sky in the Visitation panel, allowing the artist to produce the white clouds. Sanguine, a reddish stain, is probably what is used to tint the blush of a cheek and also the drops of blood on Christ’s garments. The dominant pictorial intervention, however, rests on the application of neutral color paint to model flesh and drapery. Evans favored a smooth execution, devoid of visible brush strokes, producing a feeling of water-color wash, which indeed is essentially the medium of vitreous paint on glass.

Rubens, Old Masters, and Inspiration

.jpg)

Peter Paul Rubens,

Descent from the Cross,

1612-14, Cathedral of Our

Lady, Antwerp. Photo:

courtesy Laurence ShafeRubens was an immensely admired and influential artist, with commissions from England,

Rubens, Descent

from the Cross, after

Bailey, The Great

Painters' Gospel,

Boston: W. A. Wilde

Company, 1900, fig. 151.France, Rome, as well as the Lowlands. The Descent from the Cross was

Rubens, Descent from the

Cross, chromolithograph,

possibly German, 1880s?,

private collection.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin published as a print by Lucas Vorsterman in 1620 and widely disseminated.11 The altarpiece was complemented by another painting, the artist’s Raising of the Cross in the cathedral. Thus Antwerp was a site for English-speaking visitors on the grand tour, when returning through the Lowlands after travelling from France to Italy. In 1794, the Descent from the Cross figured among the great treasures that Napoleon removed to install in the Louvre as a testimony to his conquests. It was returned in 1815 after his defeat.

The honor accorded to the painting by the 19th-century public made it a touchstone for artists. It is used again and again as the basis for stained glass installations, each one, however, differing due to materials, placement and artistic sensibilities. Popular texts on art and on religion at the turn of the century invariably included Rubens’ work.12 The humanity of the image is striking, showing the great weight of the Christ’s body descending into the arms of his followers. Christ’s foot rests on the shoulder of Mary Magdalen, in proximity to her hair, and thus recalling the moment that she washed his feet with her tears and dried them with her hair as a gesture of penitence. St John is in red, a tradition linking him to youth and passion, and the sanguine humor. The contrast between the beautifully formed but lifeless body of Christ is highlighted by the stark whiteness of the sheet that frames him. Death and the end of passion act as a foil to the dynamism of the straining bodies and the tearful faces of his followers.

The qualities of glass

Mayer and Company,

Deposition, 1909, Cathedral

of the Immaculate

Conception, (building Patrick

C. Keely, 1866-1869)

Portland Maine. Photo:

Michel M. Raguin In an era when painting, especially in oil, was clearly the dominant medium of artistic expression, the nascent field of stained glass would easily turn to emulation. To transport, in a manner, the experience the Rubens painting to local venue was compelling. Historically, painters in stained glass and in other media shared the same models – and even model books when drawings as paper became more widely used. The work in glass, however, has its own physical attraction. The clarity of the pot-metal colors was clearly distinct from the complex modeling of various tones and hues of oil paint. As the craft is truly a graphic medium, the artist’s individual application of paint matters greatly. Even when a known composition is selected for the image, the eye is intrigued by the selection of color and the graphic style. Rubens’ painting was used for a window of the Descent from the Cross from the series in the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Portland Maine, executed by the Mayer Studio (also referred to as the Royal Bavarian Glass Company of Munich, Germany) in 1909. Reconfiguring the composition to a three light window, the artist dispersed emphasis on each of the figures, adding headdresses for the Virgin and the woman below. The colors are also lightened in many areas, exploiting the lighting effects of the material of glass. The draftsmanship, especially on the body and head of Christ is vigorous and compelling. A warm brown tint appears in the striations of the hair, echoing the varied hues of the silver stain of the halo.

Parallel dissemination in the modern world of the image in print

Indeed, the question is one about recognition. What value is communicated by an image? A

Crucifixion, chromolithograph,

possibly German, 1890s?

Set in blue velvet border within

gesso wood frame with gold

paint, private collection.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin 19th-century chromolithograph of Rubens’ work could bring the Antwerp masterpiece into the middle-class home. During this era, printers developed the process of incorporating color by using multiple stones on which different colors were impressed. The image is drawn onto a stone or zinc plate with a grease-based crayon. Low

Mayer and Company,

Crucifixion, 1909, Cathedral

of the Immaculate Conception,

(building Patrick C. Keely,

1866-1869) Portland Maine.

Photo: Michel M. Raguin cost color printing finally became available to a broad public. Chromolithography was used extensively in advertising, children books, fine arts publications, posters, trade cards, and labels. The chromolithograph reduces the altarpiece to a single image devoid of architectural context. The painting is considerably lightened and the colors altered to enable easy identification of the subject matter. The dramatic contrast of dark and light so vividly incorporated in the original is lost. Yet, the essential interaction of the figures is preserved, communicating the narrative to the viewer.

The reproductive print was cherished. A chromolithograph image of the Crucifixion could be embellished by a blue velvet border that meets a gesso textured frame of flowers and leaves overlaid with a gold paint. The image is indebted to a “Nazarene” prototype, an early 19th century school of painters discussed more fully later. The many inscriptions of the banderoles are in Latin, thus making the use of the image universal, the then standard language of the Catholic Mass, even for average congregants. They would have recognized the phrases, “Father, forgive them for they know not what they do, or “Oh Lord, my God why hast thou forsaken me,” The simplicity of the scenes is compelling. The same concept and format reappears in stained glass, exemplified by another window from Portland’s Catholic Cathedral. The figures are essentially isolated; each is framed in its own space, the Virgin to the left, St. John to the right, and Mary Magdalen in the center clutching the cross. What is valued in privacy of the home is confirmed by the public.

Tradition and traditional religion

Our contemporary experience of a discourse where “art” and “religion” occupy separate spheres also compromises our respect for a world where the clergy and the devout were both primary patrons and spectators. Religion has functioned as one of the most potent forces in the shaping of societal identity. Often, historic preservation of religious structures is countered by a position: “we are dedicated to our congregants; we are not museums.” Thus we perceive a manufactured antipathy – or at the least a dichotomy - between art and religion. How might we address the explicitly Christian aspect of a much of 19th-century art where biblical subject matter permeated art and literature? How do we understand John Singer Sargent’s great murals in the Boston Public Library on the progress of religion from paganism to Christianity?13 Happily, the collectable status of the artist mitigates any concept of altering the explicitly triumphalist presentation of Christianity. At one end of the hall, the pagan gods of the Middle East crowd the ceiling. The Israelites, above a frieze of Old Testament prophets, are shown oppressed by Egypt. On the opposite wall, the pageant culminates on the Dogma of the Redemption. The Christian Trinity appears as three enthroned men in gold-trimmed robes, set behind a relief of Christ crucified redeeming the sin of Adam and Eve.

Inclusion

This study attempts to look at all the types of architectural stained glass found in the United States. It does not attempt to create divisions among imported or American products. What are in our buildings are what Americans experienced, as heterogeneous as the nation itself. The most ancient examples of our leaded and painted glass were produced by artists such as William Bolton whose model was an explicit European site, discussed in the first essay on the Anglo-American Designer. European publications, similar to the design books so essential to the cabinet makers of the 18th century, brought changes of style to American practitioners throughout this era, just as they disseminated ideas among artists in the mother country. Large portions of this trove of historic windows were designed by artists born and trained outside the country. A great many windows were also manufactured in Germany, France and England. As discussed in the essay on Ethnic Choices, often commissions were tied to familiarity with a specific religious tradition. Artists and craftsperson migrated to work in American cities; American manufacturers set up branches in Europe. Studios subcontracted to others who could enable them to meet the market demand for their work.

The field is large, rich, and filled with diversity of expression. As we move into the 21st century, we are faced with choices of what to keep and what to discard, what to preserve, what to archive, and what to neglect. Hopefully this devoted attempt to chart the breath of the leaded and painted window in architectural settings will be a contribution to the daunting task of insuring a past for our future.

REFERENCES

![]()

1. ^ Weinberg 1977, 410-413, figs. 310-321.

2. ^ La Farge has already installed the Julia Appleton McKim window in Trinity Church, Boston, at the behest of White’s partner, Charles Follen McKim, as well as in 1885 designing windows deeply attuned to the architecture of The Church of St. Paul the Apostle, New York City.

3. ^ Provenance Thomas Wright’s estate, sold in 1918. Private collection, Newport, Rhode Island.

4. ^ Contemporary artists are sometimes designing for windows in light box delays. One example is the complex work of Judith Schaechter.

5. ^ See John La Farge and the Recovery of the Sacred. [Exh. cat. McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College] (Boston, 2015) text by Jeffery Howe and others.

6. ^ See the works and the discourse included in the catalog of art at the time of Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein in Painting on Light, 2000.

7. ^ For the Le Prince family, see Martine Callias Bey, Véronique Chaussé, Françoise Gatouillat, and Michel Hérold, Les Vitraux de Haute-Normandie (Recensement des vitraux anciens de la France, vol. VI). Paris, 2001and Michel Hérold, “Les Le Prince de Beauvais et la Normandie”; “Le vitrail des Chars”; “Le vitrail de la vie de saint Jean-Baptiste”; “Les œuvres de Miséricorde”; “Les oubliés de Saint-Vincent”; “Vitraux du XVIe siècle du transept et de la nef”; “Le vitrail de l’arbre de Jessé”; “Le vitrail du Jugement dernier”; in Vitraux retrouvés de l’église Saint-Vincent de Rouen [exh. cat. Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts, (Rouen, 1995) 44-69, 114-129 et 168.

8. ^ St. Vincent was destroyed during World War II, and the windows that had been taken out for safe keeping were reinstalled in the new church of Ste. Jeanne d’Arc,

9. ^ Isabelle Lettéron and Delphine Gillot, Rouen, l'Hôtel de Bourgtheroulde, demeure des Le Roux, Connaissance du patrimoine (Rouen, 1996).

10. ^ The Buildings of England: 1958, The windows at the opposite end of the church, on either side of the organ, are also based on paintings and show scenes from the life of Christ.

11. ^ John R. Martin, ed., Rubens: The Antwerp Altarpieces - The Raising of the Cross and the Descent from the Cross - Norton Critical Studies in Art History (Norton & Company, 1969).

12. ^ For example, The Light of the World: Our Saviour in Art (London, New York, Chicago: The British-American Company, 1900), fig. 21, cited Descent from the Cross among sixty-nine great paintings. See also Henry Turner Bailey, The Great Painters' Gospel, Pictures Representing Scenes and Incidents in the Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ with Scriptural Quotations, References and Suggestions for Comparative Study (Boston: W. A. Wilde Company, 1900), fig. 151.

13. ^ 1895 (north), 1903 (south), 1916-1919 (side walls). Sally Promey, Painting Religion in Public: John Singer Sargent's Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library (Princeton NJ; Princeton University Press, 1999). In 1921 Sargent installed all of the murals in the rotunda of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.