- Ghanasyam Raturi, the Chipko poet |

CHIPKO: A case study in CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE

and NON VIOLENT DIRECT ACTION Ryan Redmond |

Dams are the "temples of modern India." - Jawaharlal Nehru, first Prime Minister of independent India |

|

ACTIVITY THREE: Understanding the history of Chipko

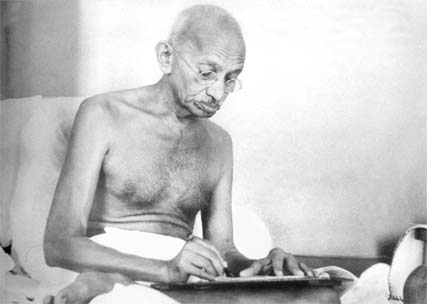

Mohandas Gandhi's notion and practice of satyagraha, the philosophy of nonviolent resistance and action aimed at getting at truth, has been instrumental in fueling the Chipko movement. CHIPKO: AN INTRODUCTION The Chipko movement, which began in 1972 in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and quickly spread west into the middle Himalayan region, is a movement of nonviolent direct action. Its purpose was, and is, to prevent the destruction of forests and to protect the environment, livelihood and ways of life for the rural villagers of the region. By the time the movement began, this region of India was undergoing a series of changes, all surrounding development activities, which "caused depletion of the forests, erosion of the soil, drying up of water resources, preemption of the firewood, the fodder, and building materials, and cooptation or destruction of much of the viable agricultural land and pasture" (Berreman, 1989, 243). By development activities what is meant is primarily road building. Following the 1963 Indo-Chinese border conflict, the Indian government began to build road networks criss-crossing the Himalaya (Berreman, 1989, 242). Just as the interstate highway system in the United States owes its origins to the Federal Highway Act of 1956 and the need for military mobilization, so too were many roads built in India with homeland defense in mind. Road construction itself created many environmental changes just as did a whole host of accompanying developments. With better transportation came easier access to forest and mineral resources. "[C]ontractors, corporations and other entrepeneurs from the distant cities of the plains" were not too far behind the road construction teams (Berreman, 1989, 242). Gandhian sarvodaya workers, who had been working in the area since the 1960's, led by Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna, set the wheel into motion in 1972 when, seriously concerned about environmental degradation and the livelihood of villagers, they confronted both government forestry workers and private contractors. The hugged trees to prevent them from being cut. Sarvodaya, a term coined, in this context, by Gandhian activist Vinoba Bhave to refer to the struggle to uplift all, even the poor and destitute masses (Berreman, 1989). At the same time, even though I've used the term "movement" above, which suggests a certain high level of uniformity and organization, environmentalist Anil Agarwal reminds us, in an article in India Today, that "The Chipko movement itself was never an organised protest. It was largely a series of discrete protests by separate Himalayan villages like Reni, Gopeshwar and Dungari-Paitoli." Despite its amorphousness, it has indeed, at various points in time, achieved a certain level of greater organization, namely under the leadership of people like Chandi Prasad Bhatt. That said, Berreman informs us that the movement, as unified as it may have been at times, has also split apart along ideological lines. He writes that Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna, the two major leaders, differ significantly in their approaches. Bhatt has become more pragmatic, is interested in the ecologically sound use of forests, including sawmills, and has viewed the Forest Department as a potential ally. To him, it is the Government of India which makes bad policy not necessarily employees of the Forest Department. Bahuguna, on the other hand, has been more of a hard liner. He has not wanted to negotiate with forestry officials, believing that they have done the most harm, has viewed the struggle in seemingly more symbolic terms and, unlike Bhatt, makes a point of courting global support and spreading his position at international conferences (Berreman, 248-249, 1989). Note: Of course, I've used Berreman's informative, but now rather dated, article on the subject. To get a more complete picture, it is necessary to consult more contemporary writing on the topic. All told, investigation of this ideological split would provide brilliant access to looking at differing methods of conflict resolution and nonviolent direct action.

Map indicating the location of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, where Chipko originated.

This somewhat dry case study is published on American University's Trade and Environment Database (TED) and while some of the writing is poorly edited, it provides a decent introduction and overview of the Chipko movement. "Hug the Trees!" Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Gauri Devi, and the Chipko Movement This article, written by Mark Shepard, provides a nice rich, descriptive narrative about the origins of the Chipko movement. Shepard is a self described "Gandhian journalist and 'alternative lifestylist,'" which is important in assessing his own perspective and biases. This article comes from a website documenting the We the Peoples: 50 Communities Awards. In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations, a non-government organization calledFriends of the United Nations conducted a program during with these awards were presented. These awards were presented to citizens' initiatives which present solutions to difficult problems. The Chipko movement was a recipient of one of these awards. "Working Together" by Usha Jesudasan This article appeared in the Indian newspaper The Hindu on June 14, 2003. "Mine, Not Yours" by Kanchi Kohli This article also appeared in The Hindu, but on March 28, 2004.

Photo of Chipko "tree huggers" from A field guide for project design and implementation - Women in community forestry published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome 1989.

II. Discuss the articles:

TED Case Study Questions 1. What does the word Chipko mean? "Hug the Trees!" Questions 1. What does Shepard mean when he writes of "oppressive government policies concerning the forests?" "Chipko Movement, India" Questions 1. In what regions of India has this Chipko movement taken place? 1. What does the word solidarity mean? 1. At the beginning of the article appears these words: "'Paharh ki haddi tootegi, desh ki dharti doobegi.' (If the backbone of the hills breaks, the plains below will be submerged)." What does this saying mean? How does the message fit into the Chipko movement?

This article provides a much richer, more comprehensive look at Chipko. of particular interest is Berreman's explication of the schism between two of the movement's primary founders. Ecology and the Politics of Survival: Conflicts Over Natural Resources in India by Vandana Shiva The ecologist and activist Shiva, in this book (the entirety of which is available online), delves into a series of case studies, both water conflicts and forest conflicts in India. There is a section specific to Chipko, but there is also a wealth of contextual and complementary information. This website, which is the home to a network of community leaders, activists and scholars from the region and from other parts of the world, offers a wealth of information. That said, it most definitely is an organization with an agenda and should be read about as such. This is the full text of Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay. The Chipko Movement, Chandi Prasad Bhatt This brief history of the Chipko Movement is interesting, but to understand its tone, one must keep inmind that Bhatt, one of the leaders of the movement, is the author.

|

This site was created by Ryan Redmond at the NEH Summer Institute "Cultures and Religions of the Himalayan Region," held at the College of the Holy Cross, Summer 2006