| History

by Phil Schneider and Daniel Riley

Mount

Saint James, or Packachoag hill (the Hill of Pleasant Springs), as it

was formerly known, has undergone great change and development over the

past two hundred years - both literally in terms of buildings and physical

alterations to the land, but also in terms of the way people have conceived

of the space. One of the individuals who worked with the Nipmucs, the

Native Americans living on the site was the Rev.

John Eliot. A congregationalist minister, Eliot preached to and taught

the "praying Indians" of Quinsigamond. Mount

Saint James, or Packachoag hill (the Hill of Pleasant Springs), as it

was formerly known, has undergone great change and development over the

past two hundred years - both literally in terms of buildings and physical

alterations to the land, but also in terms of the way people have conceived

of the space. One of the individuals who worked with the Nipmucs, the

Native Americans living on the site was the Rev.

John Eliot. A congregationalist minister, Eliot preached to and taught

the "praying Indians" of Quinsigamond.

The original plot

of fifty-two acres, purchased by Rev. James Fitton from the Parch family

farm in 1836, was described as situated "on that most delightful

eminence which bounds the flourishing town of Worcester and on the South

Packachoag.  The

spot was "eminently healthful, not to be "surpassed by any spot

in New England. Every description of the College, from the 1800s to the

present, stresses the vista from atop the hill the location permitted

residents to both see and be seen "(Nutt 741). To the north lay the

Blackstone River, and further on, the road to Hartford. The canal to Providence

created the easterly boundary, while western hills rounded off the site

(Meagher and Grattan 25). Bishop Benedict Fenwick remarked that the site

of the future College of the Holy Cross, Packachoag Hill, was "an

extensive hill watered by a little stream of pure water" (Kuzniewski

23). As Meagher and Grattan note in their history of the College, The

Spires of Fenwick, "Academe seems likely to have been confused with

Eden" (25). The

spot was "eminently healthful, not to be "surpassed by any spot

in New England. Every description of the College, from the 1800s to the

present, stresses the vista from atop the hill the location permitted

residents to both see and be seen "(Nutt 741). To the north lay the

Blackstone River, and further on, the road to Hartford. The canal to Providence

created the easterly boundary, while western hills rounded off the site

(Meagher and Grattan 25). Bishop Benedict Fenwick remarked that the site

of the future College of the Holy Cross, Packachoag Hill, was "an

extensive hill watered by a little stream of pure water" (Kuzniewski

23). As Meagher and Grattan note in their history of the College, The

Spires of Fenwick, "Academe seems likely to have been confused with

Eden" (25).

Fr.

Fitton had come from a recusant English tradition, his father having emigrated

from Preston in Lancashire, an area of England's Midlands that remained

Catholic since the Reformation. Born in Boston in 1805 he was baptized

in the church, later cathedral, of the Holy Cross on Franklin Street.

Built in a Federal style after plans donated by Charles

Bulfinch, architect of Faneuil Hall, the State House, and many of

Boston's premier buildings of the time, the church assimilated Catholics

into a New England landscape. Growing up, Fitton served Mass at the church

and took classes at the Claremont Catholic Seminary. Bishop Benedict Fenwick, Fr.

Fitton had come from a recusant English tradition, his father having emigrated

from Preston in Lancashire, an area of England's Midlands that remained

Catholic since the Reformation. Born in Boston in 1805 he was baptized

in the church, later cathedral, of the Holy Cross on Franklin Street.

Built in a Federal style after plans donated by Charles

Bulfinch, architect of Faneuil Hall, the State House, and many of

Boston's premier buildings of the time, the church assimilated Catholics

into a New England landscape. Growing up, Fitton served Mass at the church

and took classes at the Claremont Catholic Seminary. Bishop Benedict Fenwick, whose grave is at the college, ordained him on December 23, 1827. His

early ministries took him to Maine, where he preached to the local Passamaquoddy

Indians and in 1834 he was assigned to Western Massachusetts and scheduled

to say mass in Worcester once a month.

whose grave is at the college, ordained him on December 23, 1827. His

early ministries took him to Maine, where he preached to the local Passamaquoddy

Indians and in 1834 he was assigned to Western Massachusetts and scheduled

to say mass in Worcester once a month.

The development of

the site that later became Holy Cross was long and somewhat disjointed,

but indeed began with Fitton's purchase of what amounted to a farm. This

was no small feat for the time, as just two years earlier in 1835 Fitton

had struggled to buy land for a Catholic church on Temple Street in the

city. St. John's church, which now stands from its reconstruction in 1845

was made possibly only through the purchase of land by Worcester Protestants

which was then transferred to Fr. Fitton. Likewise, Fitton was aided in

his first real estate purchases for the seminary by Rejoice Newton and

William Lincoln, local Protestant men who acted as his agents, buying

three lots of pasture land (Meagher and Grattan 23).

After

convincing the wealthy contractor Tobias Boland to pay for the erection

of a two-story building in which to house his academy, Fitton was finally

ready to invite Bishop Fenwick to inspect his work. Fenwick commented

that he "was greatly pleased to see this infant institution…and

that something would grow out of it useful to the church." With settlements

in close proximity to the school, the institution would become a place

where Indians would be educated as well. In 1836, Fitton named the school

"The Mount Saint James Seminary" after his patron saint and

charged a tuition of eighty-five dollars per year, which eventually rose

to one hundred by 1840. After

convincing the wealthy contractor Tobias Boland to pay for the erection

of a two-story building in which to house his academy, Fitton was finally

ready to invite Bishop Fenwick to inspect his work. Fenwick commented

that he "was greatly pleased to see this infant institution…and

that something would grow out of it useful to the church." With settlements

in close proximity to the school, the institution would become a place

where Indians would be educated as well. In 1836, Fitton named the school

"The Mount Saint James Seminary" after his patron saint and

charged a tuition of eighty-five dollars per year, which eventually rose

to one hundred by 1840.

The purchase of the

farm was, at the time, a remarkably valuable asset. Fitton's seminary

provided assurance of nutritious vegetable and dairy products satisfied

parental concern about diet, in an age dependent for the most part on

local agriculture. The house and barn, surrounded by other private farms

on the hill, came at the cost of two thousand dollars. Funds were provided

by small donations from area Catholics, inspired by Fitton's vision of

a small boarding school on the idyllic spot. The United States Catholic

Almanac and Laity's Directory for the Year 1837 described the site as

an "eminently healthful location, which is within a few moments walk

of the centre of Worcester and junction of the rail-roads." This

beauty was also the result of the hard labor which the early students

were expected to perform for one to two hours a day. These students, mainly

Irish laborers, cut out the upper and lower terraces from the hill under

the direction of Joseph Brigden the academy's "Principal."

It was not until

1843 that the land was transferred to Bishop Fenwick, the man credited

with providing the inspiration and force of the resultant college. Fenwick

wasted no time in employing Protestant agents to buy another twenty-two

acres of the Patch farm at a public auction later that year. With these

seventy-four acres, Fenwick began the plans for his college. It is important

to note the ramifications of the debate between Fenwick and his colleagues

over whether or not to construct a day school in Boston or a boarding

school in Worcester. Throughout this conflict, Fenwick emphasized the

physical remoteness of the Mount St. James site from the urban center

of Boston as well as the nearer population of Worcester itself as an asset,

rather than a detriment. He expected that day colleges would tend to attract

students from the lower order of society economic necessity would force

many parents to withdraw their sons before they could finish the humanities

course (Kuzniewski 26). Thus the remoteness of the spot appealed to Fenwick

for both aesthetic and more pragmatic reasons.

Throughout

the rest of the 1800s, the land under college ownership gradually expanded

to include adjacent farms. During this time the college remained true

to its agricultural roots; the campus farm was still in operation: The

fall harvest of 1879 brought nearly 1000 bushels of potatoes and 105 barrels

of apples, in addition to a thriving dairy herd (Kuzniewski 136). In 1862,

then president Father Clark purchased 48 acres next the lower campus.

After the Civil War, student population growth both facilitated and demanded

the physical expansion of the college. Thus in 1900, land at the bottom

of the hill, populated by a few aging buildings, was purchased for the

sake of baseball field. Fitton Field was more or less developed in the

ensuing years, prompting Father Hanselman to extol the college's outside

with delightful walks, tennis and hand-ball courts and a large athletic

field (Kuzniewski 194). The site had always been conceived of as a self-sufficient

institution. In the 1800s that meant a farm and dairy herd, but as time

went on it came to mean athletic facilities and new dorms and a dining

hall. The dynamic definition of a college was reflected in the physical

characteristics of Holy Cross. Throughout

the rest of the 1800s, the land under college ownership gradually expanded

to include adjacent farms. During this time the college remained true

to its agricultural roots; the campus farm was still in operation: The

fall harvest of 1879 brought nearly 1000 bushels of potatoes and 105 barrels

of apples, in addition to a thriving dairy herd (Kuzniewski 136). In 1862,

then president Father Clark purchased 48 acres next the lower campus.

After the Civil War, student population growth both facilitated and demanded

the physical expansion of the college. Thus in 1900, land at the bottom

of the hill, populated by a few aging buildings, was purchased for the

sake of baseball field. Fitton Field was more or less developed in the

ensuing years, prompting Father Hanselman to extol the college's outside

with delightful walks, tennis and hand-ball courts and a large athletic

field (Kuzniewski 194). The site had always been conceived of as a self-sufficient

institution. In the 1800s that meant a farm and dairy herd, but as time

went on it came to mean athletic facilities and new dorms and a dining

hall. The dynamic definition of a college was reflected in the physical

characteristics of Holy Cross.

Of significant note

in the latter development of the College's physical site are the gates

and the installation of interstate 290. Initially there was only a gate

at the entrance to Linden Lane; this was supplemented in 1923 by a gate

for Fitton Field, farther down the hill, and an iron fence linking the

two (Kuzniewski 231). The purpose was symbolism more than security, providing

an elegant distinction between the college and the street. Notably, at

this time college athletics were a source of pride and disportment for

city residents as well as students. Such coincidence of interests, however,

was not eternal. As the college grew and defined itself, so did the surrounding

area.

The

road to Southbridge was completed in 1902 (Nutt 994), thereby establishing

a new boundary with the college in place of the canal, which had formerly

defined the site. Increased traffic at the base of the hill no doubt gave

further psychological force to the college's location above. Local transportation

interests only spawned a conflict in the 1950s, when the Massachusetts

Department of Public Works proposed plans for I-290. The road was originally

slated to run twenty yards behind Kimball, arousing vehement opposition

among the Jesuits and other college supporters. The conflict was painted

in terms of the college versus the city, given that the college was not

only accused of delaying progress, but proposing an alternative route

requiring the destruction of local factories (Kuzniewski 326-29). This

route was eventually chosen and only two small sections of college land

taken for the project. The line between college and city had, however,

been firmly drawn. The

road to Southbridge was completed in 1902 (Nutt 994), thereby establishing

a new boundary with the college in place of the canal, which had formerly

defined the site. Increased traffic at the base of the hill no doubt gave

further psychological force to the college's location above. Local transportation

interests only spawned a conflict in the 1950s, when the Massachusetts

Department of Public Works proposed plans for I-290. The road was originally

slated to run twenty yards behind Kimball, arousing vehement opposition

among the Jesuits and other college supporters. The conflict was painted

in terms of the college versus the city, given that the college was not

only accused of delaying progress, but proposing an alternative route

requiring the destruction of local factories (Kuzniewski 326-29). This

route was eventually chosen and only two small sections of college land

taken for the project. The line between college and city had, however,

been firmly drawn.

Fenwick

and O'Kane: The Heart of the College by Deanna DeArango

As with most college

campuses, the many buildings on the campus of Holy Cross seem to represent

architectural excellence and grand structures. However, what is often

not realized at first glance at the beautiful buildings of Holy Cross

is that the architecture of each building is reflective of the time period

in which it was built. The eclectic Revival styles that characterize Fenwick

Hall of the 19th century are very different from the pared-down Modernist

style in which the dorms on Easy Street were built in the 20th century.

At certain times, specific architectural styles were used in the construction

of new buildings not only all over the city of Worcester, but all over

the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. One can see similarities in appearances

of buildings built during the same time period, and also built by the

same architect. As it exists today, Fenwick Hall is a multifaceted building

complex that encompasses many architectural styles characteristic of the

time in which they were added.

In

1843, construction of the site that was to become the main academy building

began. At the time, Greek Revival was an important style, especially in

Worcester which boasted a number of churches and public buildings, as

well as a significant number of residences with Greek revival principles.

Greek Revival was extremely popular in the United States in the early

19th century and was associated with ancient classical virtues such as

knowledge and strength. Fenwick Hall was originally constructed using

traditional materials of brick and granite. In this first incarnation,

the building housed nearly all of the main offices and activity areas,

including offices, classrooms, dormitories and a chapel. In the late 1840's

Fenwick was expanded by the addition of an east wing. This original building

of Fenwick Hall was largely destroyed by a fire in 1852 and needed to

be entirely rebuilt. Captain Edward Lamb was the architect for this project.

The parts of the east wing that remained after the fire were integrated

into the new building, completed in 1853. Original drawings from both

the 1843 and 1853 building plans show similarities of the Greek Revival

design of the building. In

1843, construction of the site that was to become the main academy building

began. At the time, Greek Revival was an important style, especially in

Worcester which boasted a number of churches and public buildings, as

well as a significant number of residences with Greek revival principles.

Greek Revival was extremely popular in the United States in the early

19th century and was associated with ancient classical virtues such as

knowledge and strength. Fenwick Hall was originally constructed using

traditional materials of brick and granite. In this first incarnation,

the building housed nearly all of the main offices and activity areas,

including offices, classrooms, dormitories and a chapel. In the late 1840's

Fenwick was expanded by the addition of an east wing. This original building

of Fenwick Hall was largely destroyed by a fire in 1852 and needed to

be entirely rebuilt. Captain Edward Lamb was the architect for this project.

The parts of the east wing that remained after the fire were integrated

into the new building, completed in 1853. Original drawings from both

the 1843 and 1853 building plans show similarities of the Greek Revival

design of the building.

In 1867, Fenwick

Hall was largely expanded and rebuilt by prominent Worcester architect

Elbridge Boyden, who also designed the Cambridge

Street School. An additional floor was added to the building, a new

west wing was built, the towers were added and the mansard roof built.

Boyden's work did away with a great deal of the original Greek Revival

design of the building and incorporated elements of the Collegiate Gothic

and Second Empire styles. (Collegiate Gothic was a style, inspired by

the English, used in many university buildings. Second Empire was a style

modeled after architecture of the time of Napoleon III and was popular

in the late 1860's. It is characterized by pavilions, pedimented dormers

and French Renaissance detailing.) Boyden also built Worcester's Cathedral

of St. Paul and Washburn

Machine Shops at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. The architecture

of Fenwick and the Washburn Machine Shops are very similar, as can be

seen in the buildings' repetition of many windows with white arched moldings,

high white towers, detailed cornices, and a brick outside.

Fenwick

Hall was enlarged again in 1875 under the auspices of Boston architect

Patrick W. Ford, who also built St. Peter's Catholic Church on Main Street

in 1893. O'Kane Hall was built and attached to the west end wall of Fenwick

in 1895 by the firm Fuller & Delano. Finally, Commencement Porch,

designed in Georgian Revival style, was added to the front of Fenwick

Hall in 1907. (Georgian Revival, also referred to as Colonial Revival,

mirrored the architecture of Britain under the reign of Kings George I,

George II, George III, and was derived from classical Greek architecture.)

The addition of Commencement Porch is interesting in comparison to other

architectural elements also appearing in prominent buildings in Worcester

at the same time. The Colonial Revival also characterized the architecture

of the American

Antiquarian Society and the Worcester

Women's' Club. Fenwick

Hall was enlarged again in 1875 under the auspices of Boston architect

Patrick W. Ford, who also built St. Peter's Catholic Church on Main Street

in 1893. O'Kane Hall was built and attached to the west end wall of Fenwick

in 1895 by the firm Fuller & Delano. Finally, Commencement Porch,

designed in Georgian Revival style, was added to the front of Fenwick

Hall in 1907. (Georgian Revival, also referred to as Colonial Revival,

mirrored the architecture of Britain under the reign of Kings George I,

George II, George III, and was derived from classical Greek architecture.)

The addition of Commencement Porch is interesting in comparison to other

architectural elements also appearing in prominent buildings in Worcester

at the same time. The Colonial Revival also characterized the architecture

of the American

Antiquarian Society and the Worcester

Women's' Club.

Fenwick Hall's architectural

intricacy, grand size, prominent towers, symmetrical windows and classic

columns portray its importance on campus. It is perhaps one of the most

striking buildings on campus because of its complex combination of many

rich architectural forms. Its form is associated with the typical brick

"L" shaped or single block style familiar to other college campuses

of its time such as Yale's Connecticut

Hall or Georgetown's Healy

Hall.

Expansion

and a new Renaissance Style : St. Joseph's Chapel and Dinand Library

by Katie Mahoney

Dinand

Library and St. Joseph's Chapel were built as part of the expansion of

the College after World War 1. The Boston architectural firm of Maginnis

and Walsh (Charles McGinnis (1867-1955) was commissioned to design both

projects, which would for the first time provide defined spaces for worship

and study on the campus. The function of library and chapel were once

housed in Fenwick Hall; now as separate buildings they announce their

function through their forms and details. Having previously designed buildings

for Boston

College in the Gothic Revival style, Maginnis and Walsh altered their

style to Renaissance Revival for the Holy Cross projects. This style was

in the tradition of the Jesuit architecture of the late 16th century,

which sought to fight against Reformation by constructing beautifully

ornate places of worship. The first evidence of such design was in that

of the temple of the Jesuit Order in Rome, called Il

Gesu, built in the 1570s. Jesuit churches throughout Europe such as

St. Francis Xavier

in Hronda, Belarus were often striking elements in the urban landscape. Dinand

Library and St. Joseph's Chapel were built as part of the expansion of

the College after World War 1. The Boston architectural firm of Maginnis

and Walsh (Charles McGinnis (1867-1955) was commissioned to design both

projects, which would for the first time provide defined spaces for worship

and study on the campus. The function of library and chapel were once

housed in Fenwick Hall; now as separate buildings they announce their

function through their forms and details. Having previously designed buildings

for Boston

College in the Gothic Revival style, Maginnis and Walsh altered their

style to Renaissance Revival for the Holy Cross projects. This style was

in the tradition of the Jesuit architecture of the late 16th century,

which sought to fight against Reformation by constructing beautifully

ornate places of worship. The first evidence of such design was in that

of the temple of the Jesuit Order in Rome, called Il

Gesu, built in the 1570s. Jesuit churches throughout Europe such as

St. Francis Xavier

in Hronda, Belarus were often striking elements in the urban landscape.

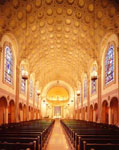

Built

in 1922, St. Joseph's Chapel was constructed as a memorial to the alumni

of Holy Cross who served in World War I. The primary shape of the building

is that of an elongated rectangular box with a triangular cap. Flanking

the primary rectangle are two smaller rectangular boxes, above which is

a bank of arched windows. The exterior of the structure is in red brick

and contrasting light stone. Three wooden doors are situated at the front

of the chapel, and a fourth door with a small stone balcony is situated

centrally above the entrances. Evenly spaced in front of the doors are

four large Corinthian columns, which are mirrored by stone pilasters on

the façade, clearly evoking the elegance it Renaissance precedent.

A front view of the chapel presents the observer with a sense of verticality,

the large columns extending from ground to pediment pulling the eye upward

and dominating the facade. The thickness of the columns in proportion

to the façade presents, at the same time, a solid, grounded effect.

The smaller outcroppings on either side of the structure serve to anchor

it as well, though they seem somewhat lost in the overall strength of

the central core of the structure. Atop the columns, the ornately carved

pediment is full of detail and beautifully crafted, and the golden cross

on top of the structure adds elegance and energy to the building. Built

in 1922, St. Joseph's Chapel was constructed as a memorial to the alumni

of Holy Cross who served in World War I. The primary shape of the building

is that of an elongated rectangular box with a triangular cap. Flanking

the primary rectangle are two smaller rectangular boxes, above which is

a bank of arched windows. The exterior of the structure is in red brick

and contrasting light stone. Three wooden doors are situated at the front

of the chapel, and a fourth door with a small stone balcony is situated

centrally above the entrances. Evenly spaced in front of the doors are

four large Corinthian columns, which are mirrored by stone pilasters on

the façade, clearly evoking the elegance it Renaissance precedent.

A front view of the chapel presents the observer with a sense of verticality,

the large columns extending from ground to pediment pulling the eye upward

and dominating the facade. The thickness of the columns in proportion

to the façade presents, at the same time, a solid, grounded effect.

The smaller outcroppings on either side of the structure serve to anchor

it as well, though they seem somewhat lost in the overall strength of

the central core of the structure. Atop the columns, the ornately carved

pediment is full of detail and beautifully crafted, and the golden cross

on top of the structure adds elegance and energy to the building.

Leading

up to the entrance and columns is a short flight of stairs which stretches

across the width of the structure. These steps serve to elevate those

attending the Chapel to a place above the everyday, and lead them into

the beautiful stone and marble interior. High vaulted ceilings are covered

with a geometric pattern of octagons and squares which recess into it,

highlighted by gold paint. Such designs were common in Renaissance church

architecture, one such example is Alberti's Saint

Andrea in Mantua, Italy, designed in 1470. Unlike their Renaissance

predecessors, however, these vaults are made of plaster instead of stone.

This saves both time and money in the construction process and allows

the designer more structural flexibility. Rows of columns and arches line

the sides of the chapel, with two rows of pews flanking a main aisle that

leads along the central axis towards the altar. Stained glass, polished

marble, and more gold detailing illuminate the interior space and give

it an elegant and reverent appearance. Leading

up to the entrance and columns is a short flight of stairs which stretches

across the width of the structure. These steps serve to elevate those

attending the Chapel to a place above the everyday, and lead them into

the beautiful stone and marble interior. High vaulted ceilings are covered

with a geometric pattern of octagons and squares which recess into it,

highlighted by gold paint. Such designs were common in Renaissance church

architecture, one such example is Alberti's Saint

Andrea in Mantua, Italy, designed in 1470. Unlike their Renaissance

predecessors, however, these vaults are made of plaster instead of stone.

This saves both time and money in the construction process and allows

the designer more structural flexibility. Rows of columns and arches line

the sides of the chapel, with two rows of pews flanking a main aisle that

leads along the central axis towards the altar. Stained glass, polished

marble, and more gold detailing illuminate the interior space and give

it an elegant and reverent appearance.

Dinand

Library dates between 1925 and 1927, named in honor of Bishop Joseph N.

Dinand, S.J., a former president of the college. It was built to house

the college library as well as the college museum and undergraduate activities

such as the debate club and student publications. The primary shape of

the front of the structure is a long rectangular box with columns stretching

across the center portion of the building. The original structure had

heavy temple vault doors at the entrance, which were later replaced by

glass to provide light and a view of the space within. Patrons entered

at the museum level and proceeded up a flight of stairs to the main reading

room. Below the reading room were the stacks used to hold the library's

many books and periodicals. The library's collection grew substantially

throughout the mid 1900s, necessitating the addition to the original structure.

The Joshua

and Leah Hiatt wings, the gift of Jacob

Hiatt, were built in 1977 and dedicated to the memory of the victims

of the Holocaust. Set predominantly below ground, they allowed the original

setting of the building to remain untouched. In a modern style of metal

and glass, the wings compliment the classical brick and stone structure

without compromising its integrity and stature. Dinand

Library dates between 1925 and 1927, named in honor of Bishop Joseph N.

Dinand, S.J., a former president of the college. It was built to house

the college library as well as the college museum and undergraduate activities

such as the debate club and student publications. The primary shape of

the front of the structure is a long rectangular box with columns stretching

across the center portion of the building. The original structure had

heavy temple vault doors at the entrance, which were later replaced by

glass to provide light and a view of the space within. Patrons entered

at the museum level and proceeded up a flight of stairs to the main reading

room. Below the reading room were the stacks used to hold the library's

many books and periodicals. The library's collection grew substantially

throughout the mid 1900s, necessitating the addition to the original structure.

The Joshua

and Leah Hiatt wings, the gift of Jacob

Hiatt, were built in 1977 and dedicated to the memory of the victims

of the Holocaust. Set predominantly below ground, they allowed the original

setting of the building to remain untouched. In a modern style of metal

and glass, the wings compliment the classical brick and stone structure

without compromising its integrity and stature.

A monumental flight

of stairs leads up to the entrance of Dinand Library, providing those

who seek to enter with a similar experience of ascension as that of entering

the chapel. These stairs, however, have a wider tread and provide a more

fluid journey from the street level to the entrance. The columns of the

library are smaller and do not dominate the façade in the same

way as those on the chapel, and emphasize horizontal flow instead of vertical.

Again, brick and granite are the primary materials on the exterior of

the structure.  The

interior is also mainly in stone, with the focus on the expansive main

reading room. A high ceiling is sectioned off in a grid-like pattern,

embellished by gold and painted trim. Like those in the ceiling of the

Chapel, the geometric recessions in that of the reading room have Renaissance

precedent in buildings such as the Teatro Olimpico, designed by Palladio

in Vicenza from 1580-84. Large wooden candelabra are suspended from the

ceiling, adding to the stateliness of the space. The columns from the

exterior are repeated again here around three sides of the room, and carvings

along the top of the interior walls add detail and elegance. The

interior is also mainly in stone, with the focus on the expansive main

reading room. A high ceiling is sectioned off in a grid-like pattern,

embellished by gold and painted trim. Like those in the ceiling of the

Chapel, the geometric recessions in that of the reading room have Renaissance

precedent in buildings such as the Teatro Olimpico, designed by Palladio

in Vicenza from 1580-84. Large wooden candelabra are suspended from the

ceiling, adding to the stateliness of the space. The columns from the

exterior are repeated again here around three sides of the room, and carvings

along the top of the interior walls add detail and elegance.

Like St. Joseph's

Chapel, this building is a place of higher meaning. The sheer size of

the building and its Renaissance styling conveys importance and a seriousness

of purpose while proclaiming the ideals of knowledge and discovery. There

was some discussion at the time of its creation that the library was too

grandiose a project for a Jesuit institution, however such opposition

was overcome and the project was built as designed. Like the Chapel it

is a structure with strength, character, and dignity, which seeks to bring

ordinary people into a world above and beyond their daily routine and

envelop them in greatness.

Bibliography

Lowry, Bates. Renaissance

Architecture. New York: George Braziller, Inc. 1962.

Kuzniewski, S. J. Anthony J. Thy Honored Name: A History of the College

of the Holy Cross, 1843-1994. Washington, DC: Catholic University

of America Press. 1999.

Maginnis, Charles. "The New Chapel (Architect's Description)".

Holy Cross Purple Magazine. May 1924 : 828.

Meagher, Walter J. and Grattan, William J, The Spires of Fenwick: A

History of the College of the Holy Cross, 1843-1963. New York: Vantage

Press, 1966.

Metelskaya, Natalie. "Minsk Review: Hrodna Farny Church". http://www.minskreview.com/n7/hrodna-e.html

Nutt, Charles. History of Worcester and Its People. New York: Lewis

Publishing Co, 1919.

Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson, and Abbot, Architects. "Library Feasibility

Survey for the College of the Holy Cross". June 1975. Boston, MA.

|