Stained Glass by Sarah Wyman Whitman at

Stained Glass by Sarah Wyman Whitman at

Central Congregational Church

Lucy Moye

Some of Sarah Wyman Whitman’s finest work at Central Congregational Church can be found in its stained glass windows. With varied styles and techniques, these windows are representative of the artist’s ability to render  different designs and formats in this remerging media. The Worcester commission was actually the crucible for the artist’s development, providing the foundation for her long, distinguished career.

different designs and formats in this remerging media. The Worcester commission was actually the crucible for the artist’s development, providing the foundation for her long, distinguished career.

The art of stained glass is a varied, collaborative enterprise; frequently different individuals are involved in the design, cutting of the glass segments, painting, and in the assembling and installation of windows. Whitman was the designer of the windows, but her studio Lily Glass Works in Boston, assembled the designs. The studio had at least two men cutting the glass and soldering the lead cames together to create the pieces. Elements, such as faces, were executed in vitreous paint after her watercolor designs by employees of the workshop. This was the standard practice of glass studios. However, it is possible that the windows of the parlor in Central Congregational Church, which were completed with cold paint, could have been done by Whitman herself due to the remarkable resemblance to her works on canvas.

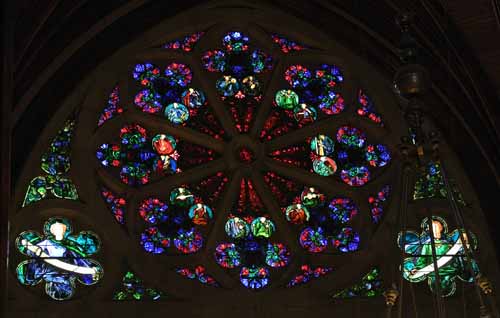

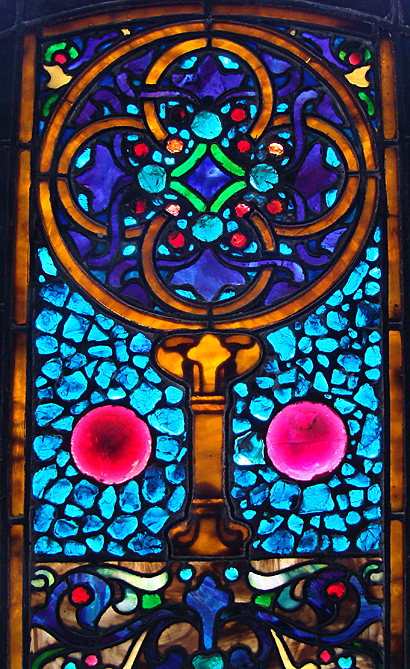

Rose Window

The rose is one of the most original elements of the interior decoration. The outer petals of the rose are in red cathedral glass. A solid red is too dense and will block most of the light; thus the glass used is mingled with uncolored material, resulting in streaked and even transparent elements in some places. This is the traditional technique for stained glass dating back to the art’s creation, and most likely was used throughout the presence of Lily Glass Works. As every piece is hand made and diverse, light enters differently through each and a spectrum of red creates an engaging visual. The orange jewels in the central circle are three-dimensional and faceted. The jewels are created by dropping hot glass pieces into molds and then firing them so that they take the desired shape. They are remarkable when struck by light, and add depth to the rose.

The Rose of the Brimmer Window of Memorial Hall at Harvard University, installed in 1896 is another example of Whitman’s work. Here she built on her experience in Worcester and created a large and even more elaborate and colorful piece. Each of these rose windows has unusually dark tonalities, creating a dramatic effect when sunlight strikes the glass. Central Congregational shows Whitman’s sophisticated intensity and denseness of color, despite being her first large-scale commission.

The Rose of the Brimmer Window of Memorial Hall at Harvard University, installed in 1896 is another example of Whitman’s work. Here she built on her experience in Worcester and created a large and even more elaborate and colorful piece. Each of these rose windows has unusually dark tonalities, creating a dramatic effect when sunlight strikes the glass. Central Congregational shows Whitman’s sophisticated intensity and denseness of color, despite being her first large-scale commission.

Floral Windows

The most common type of window found in Central Congregational is a floral design in lead with translucent and colored glass. These windows are located on the balcony and the entryway near the front doors. The floral designs in all of Whitman’s work are grounded in forms true to nature. For example, the leaves of a fig tree, a biblically significant plant

The most common type of window found in Central Congregational is a floral design in lead with translucent and colored glass. These windows are located on the balcony and the entryway near the front doors. The floral designs in all of Whitman’s work are grounded in forms true to nature. For example, the leaves of a fig tree, a biblically significant plant  (Proverbs 27:18; the Budding Fig Tree, Luke 21:29; or the parable of the Barren Fig Tree, Mark 11: 20) mirror those found in these windows. There are five leaves emerging from each stem with very dramatically sculpted veins, and both of these aspects are notably visible in Whitman’s designs. The fig tree is representative of Israel, as the plant is native to that area, making this botanically allusion perfect for the religious setting.

(Proverbs 27:18; the Budding Fig Tree, Luke 21:29; or the parable of the Barren Fig Tree, Mark 11: 20) mirror those found in these windows. There are five leaves emerging from each stem with very dramatically sculpted veins, and both of these aspects are notably visible in Whitman’s designs. The fig tree is representative of Israel, as the plant is native to that area, making this botanically allusion perfect for the religious setting.

Transparent Glass

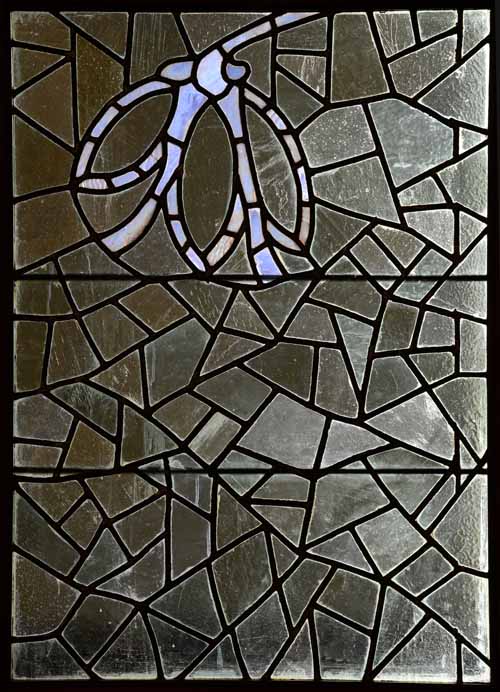

Transparent glass was also a part of Central Congregational’s original plan, exemplified by the round window in the stairway to the balcony. This rounded work has no color, no three dimensionalities, and no drama. There is only simplicity of design. Rather than letting the glass dictate the window, here the curves of the lead take center stage. Leading in organic forms also appears in windows of cruciform design in Christ Church in Andover, Massachusetts as seen on the left. Such work parallels

Transparent glass was also a part of Central Congregational’s original plan, exemplified by the round window in the stairway to the balcony. This rounded work has no color, no three dimensionalities, and no drama. There is only simplicity of design. Rather than letting the glass dictate the window, here the curves of the lead take center stage. Leading in organic forms also appears in windows of cruciform design in Christ Church in Andover, Massachusetts as seen on the left. Such work parallels  Whitman’s elegance and linear silhouettes that characterize her book covers.

Whitman’s elegance and linear silhouettes that characterize her book covers.

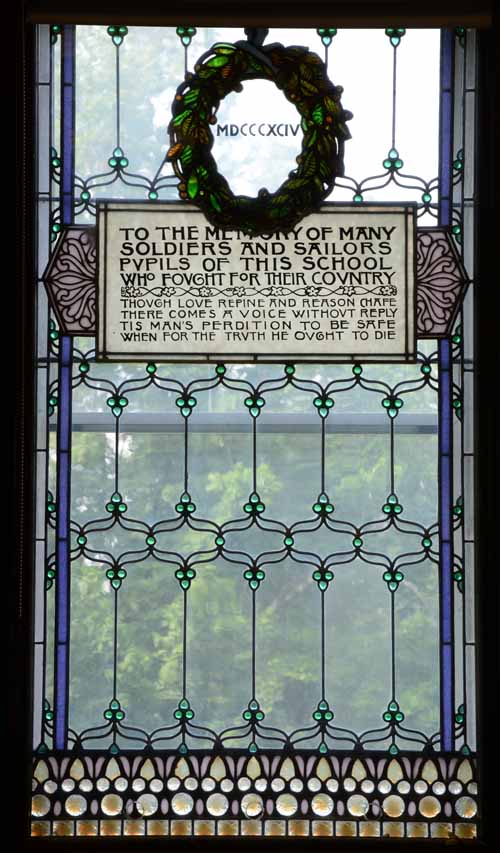

A commission similar to Central Congregational, motivated by collegial friendshipand exchange, was received for Berwick Academy, Maine in 1894. Sarah Orne Jewett, for whom Whitman designed book covers, asked the artist to make the almost 100 windows for the new William Hayes Fogg Memorial Library. The Memorial Window, below on the left, honoring those who served in the War Between the States shows vertical stems of lead tracery and transparent glass. Its borders contain three-dimensional bosses or jewels. Probably in 1901, Jewett also commissioned an uncolored, flat, leaded window honoring her father, Theodor Herman Jewett for Bowdoin College. It was installed in Bowdoin’s Memorial Hall (now Pickard Theater), to the right.

Jewels as well as lattice work appear again in  Whitman’s Phillips Brooks Memorial Window in Trinity Church’s Parish House in Boston, Massachusetts, on the right. March 12, 1896, she wrote, “The little memorial of Mr. Brooks, which my Bible Class has long dreamed of, is now finished and waiting to be put up at Easter," (SWW Letters, 1907). Whitman noted in an article that, “jewels can be used at the intersection of the quarries and the border made with delicate string-lead and enhanced with richer leading whenever the construction makes use necessary.” (Handicraft 2/6 (1903).

Whitman’s Phillips Brooks Memorial Window in Trinity Church’s Parish House in Boston, Massachusetts, on the right. March 12, 1896, she wrote, “The little memorial of Mr. Brooks, which my Bible Class has long dreamed of, is now finished and waiting to be put up at Easter," (SWW Letters, 1907). Whitman noted in an article that, “jewels can be used at the intersection of the quarries and the border made with delicate string-lead and enhanced with richer leading whenever the construction makes use necessary.” (Handicraft 2/6 (1903).

Divider Windows

Divider Windows

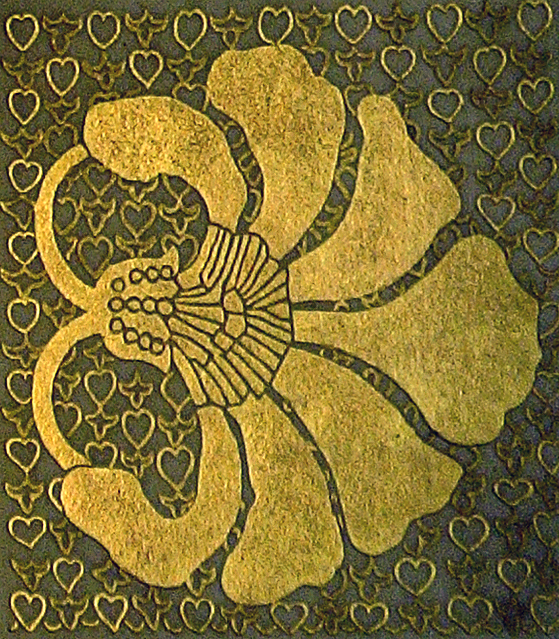

The divider windows are highly typical of Whitman’s style as they also contain a floral motif. They form a part of the wall between the front doors and the main body of the church. Whitman was fond of using translucent cathedral glass with lead forming the design. Typically, she used botanical forms, which can also be found in her well-known book cover designs. Once again, the use of the specific species of flower is chosen with symbolism in mind. These are Galanthus nivalis, or snowdrops, which are the first

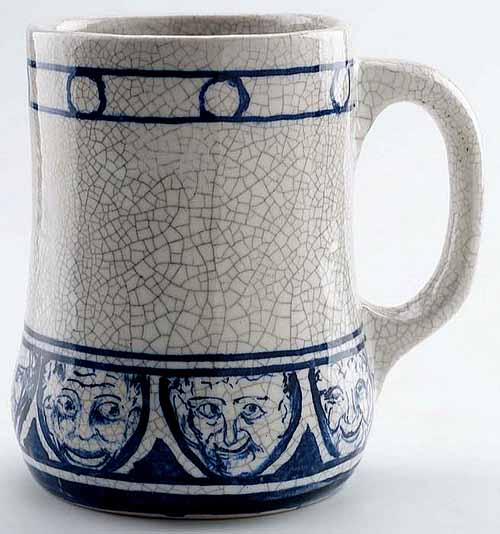

species of flower is chosen with symbolism in mind. These are Galanthus nivalis, or snowdrops, which are the first  flowers to emerge after the winter months. The flowers symbolize the renewal of spirit that one can achieve by becoming a faithful person. This window also displays Whitman’s intelligence as a designer in its exploitation of an aesthetic lattice. Similarities can be seen in the popular Arts & Crafts crackle glaze, by a mug decorated by Hugh C. Robertson between 1896-1907 for his firm, Dedham Pottery, Dedham, Massachusetts (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,

flowers to emerge after the winter months. The flowers symbolize the renewal of spirit that one can achieve by becoming a faithful person. This window also displays Whitman’s intelligence as a designer in its exploitation of an aesthetic lattice. Similarities can be seen in the popular Arts & Crafts crackle glaze, by a mug decorated by Hugh C. Robertson between 1896-1907 for his firm, Dedham Pottery, Dedham, Massachusetts (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,  1992.281 Gift of Florence Bartlett Storer). These diagonal lines also represent a technical choice by Whitman to prevent buckling. Through careful planning, Whitman avoids the potential problem of too many horizontal lines that may buckle as they bear the weight of the glass.

1992.281 Gift of Florence Bartlett Storer). These diagonal lines also represent a technical choice by Whitman to prevent buckling. Through careful planning, Whitman avoids the potential problem of too many horizontal lines that may buckle as they bear the weight of the glass.

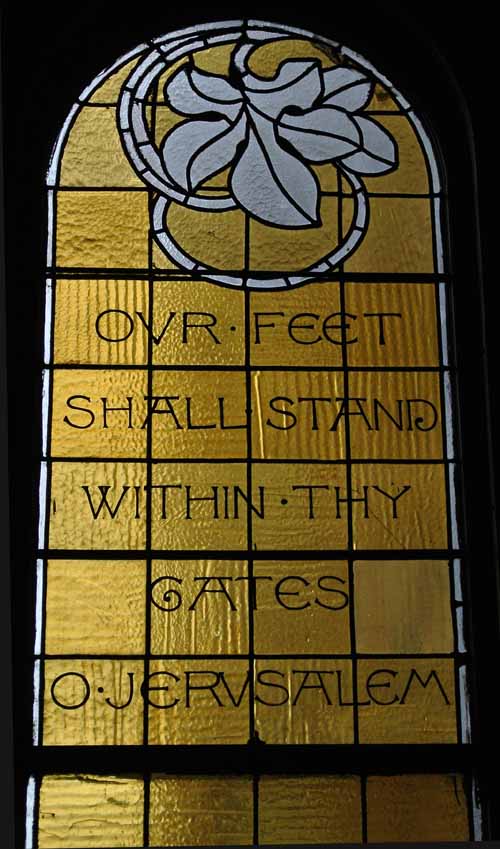

Jerusalem Window

Vitreous paints were used in Central Congregational, as well. This solid black paint of ground glass is fired to the surface to form lettering, as seen in the church’s Jerusalem window. The text used on this window is found in many of Whitman’s works, both in glass and in her book covers. It is a font specifically created by Whitman and is a great tool to recognize her creations due to its uniqueness. This window also had interesting yellow toned translucent cathedral glass, and is topped by the vegetal design above, which is once again a fig tree. A symbol of Israel in a window about Jerusalem is very fitting, and is surely an intentional choice by Whitman.

Opalescent Glass

Opalescent glass, an American invention of the 1880’s, was becoming increasingly popular at this time in part due to the innovative work of John La Farge in Trinity Church in Boston. La Farge had been developing the modern technique for a few years prior to its application in Boston and explained in his application for patent protection:

Opalescent glass, an American invention of the 1880’s, was becoming increasingly popular at this time in part due to the innovative work of John La Farge in Trinity Church in Boston. La Farge had been developing the modern technique for a few years prior to its application in Boston and explained in his application for patent protection:

“This opal glass will be more or less opaque or milky in parts . . . I am enabled by checking or graduating the amount of light in this way, to gain effects as to depth, softness, and modulation of color . . . These opalescent and iridescent effects may be enhanced by the greater or less smoothness of one or both surfaces of the opalescent glass, and by its thickness, and the glass may be waved, corrugated, or roughened in molds, or be hammered or rolled or be stamped or treated to accord with the design . . . In some instances I find it very advantageous to back colored glass of ordinary construction with independent pieces of opal glass, one or more layers of either being used, according to the effect desired . . . On a cloudy or dark day a window containing opal glass shows such a quality of color and appears as if lighted by the sun. In the day time this opal-glass window seen from outside, in variety of color, resembles mosaic work and presents a highly ornamental effect.”

Whitman was attracted to these new ideas, as she was a lover of color and painter, as was La Farge. At a time when opalescent glass was new and sometimes criticized by traditionalists, Whitman argued for its adaptation. She described the material as “a new form of stained glass, in which it is possible to attain an infinite variety of tones in the same sheet” and when both opal and color are mingled “there is a magnificence of effect never seen before” (Handicraft 2/6 (1903). An example of her usage of brilliant colors through opalescent material is visible in the Groton School Phillips Brooks Memorial Window in the swirling shades of green, above to the left.

There are inserts of opalescent glass at Central Congregational in the flower forms of the divider between the front doors and the main church, to the right. The glass is white with a pearly sheen. It is a simple and small application of  opalescence, but it is remarkable in that the patent by John La Farge was only written five years before. She was experimenting in a technique that was still very new.

opalescence, but it is remarkable in that the patent by John La Farge was only written five years before. She was experimenting in a technique that was still very new.

Whitman’s greatest achievement in opalescent can be found in her two windows for Memorial Hall at Harvard University The Chevalier Bayard or “Brimmer” window in the transept of 1896, on the left, and Honor and Peace of 1900 in the Hall, on the right. Her use of opalescent glass here, in conjunction with lead as a painterly outline, is quite  visually stunning. This window displays the multicolored consistency of the glass. Colors are a unifying factor in Whitman’s windows. The green of the Groton window is visible in the clothing of the soldiers in this Harvard piece.

visually stunning. This window displays the multicolored consistency of the glass. Colors are a unifying factor in Whitman’s windows. The green of the Groton window is visible in the clothing of the soldiers in this Harvard piece.

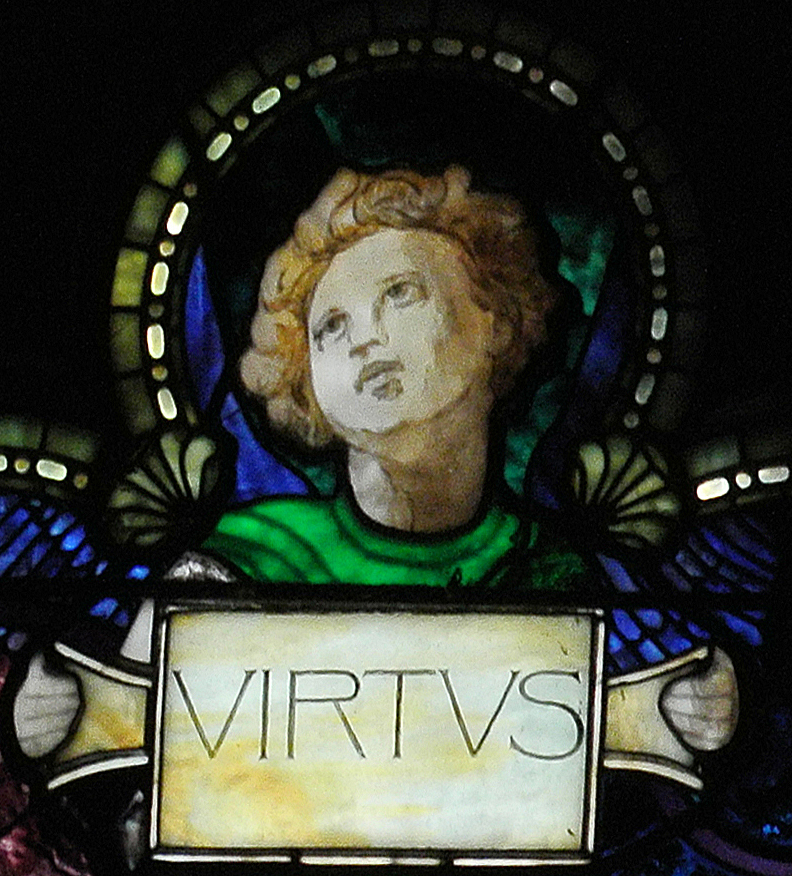

Upon a closer examination of the painted details of the angels’ faces, shown at the beginning of this essay, for example, one can see how the features are almost like a watercolor. This was done with vitreous paint consisting of finely ground glass and iron or copper oxide mixed with a liquid, most commonly gum Arabic, and applied to the glass with a brush. The painted glass is then fired so the ground glass in the paint fuses to the surface to yield a lasting image. This technique can create three-dimensional effects,  such as shading and outlines. Whitman also uses plating, which is the layering of multiple sheets of glass in one window. These layers have lead cames soldered together to support the structure. The lead of the wings appears to be behind a layer of glass, creating softer lines and shading, as seen above in Honor and Peace. There are as many as seven layers of plating in some places in this window. Whitman argued that this method of construction “enables the designer to work with a fuller palette and thus to reach more subtle and enduring results” (Handicraft 2/6 (1903).

such as shading and outlines. Whitman also uses plating, which is the layering of multiple sheets of glass in one window. These layers have lead cames soldered together to support the structure. The lead of the wings appears to be behind a layer of glass, creating softer lines and shading, as seen above in Honor and Peace. There are as many as seven layers of plating in some places in this window. Whitman argued that this method of construction “enables the designer to work with a fuller palette and thus to reach more subtle and enduring results” (Handicraft 2/6 (1903).

Another example of a window with such techniques can be found at First Parish Church in Brookline, Massachusetts. The Lowell Window, on the left, was created to honor the Lowell family in 1887. This shares similar compositions and selections of material as the windows in Memorial Hall. These works are some of her finest in her stained glass career.

The Parlor Windows

Central Congregational’s parlor windows display the technique of silver stain,

Central Congregational’s parlor windows display the technique of silver stain, a permanent application that tints glass varying shades of yellow via a chemical

a permanent application that tints glass varying shades of yellow via a chemical  process that changes the very state of theglass. Some of theflowers and leaves received an additional application of cold paint in blues, reds, and greens. Cold paint is not firedand fused to the glass, but applied without heat; this paint has failed onseveral segments of each set of these windows. Despite this unfortunateloss, the remaining flowers present a perfect example of Whitman’s painterlyskill. A painting of hers from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston titled Rhododendrons is similar in form and technique, most notably in the contrast of light and dark and the quality of the brushstrokes.

process that changes the very state of theglass. Some of theflowers and leaves received an additional application of cold paint in blues, reds, and greens. Cold paint is not firedand fused to the glass, but applied without heat; this paint has failed onseveral segments of each set of these windows. Despite this unfortunateloss, the remaining flowers present a perfect example of Whitman’s painterlyskill. A painting of hers from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston titled Rhododendrons is similar in form and technique, most notably in the contrast of light and dark and the quality of the brushstrokes.

The Lost Windows

Many of Whitman’s windows in Central Congregational have been lost. Photographs from about 1910 show two windows with a lattice structure similar to that found in the divider windows currently in the church. They also show wreaths similar to the Groton school Brooks panel in opalescent glass, meaning that they would be the most expensive of all the windows in the church. Some of the segments have the pebble effect used by La Farge in his Christ Preaching window of 1883 at Trinity Church in Boston and later by Whitman in her Lowell window at First Church in Brookline. The pebbled pieces of glass are an innovative and remarkable way to diverge from tradition while still creating an aesthetic and tactile background. The windows at Central Congregational were replaced by the work of Reynolds, Francis, & Rohnstock Studio in 1946.

Works Referenced:

Hutchins, Francis G., Stained Glass Pragmatism: Sarah Wyman Whitman’s Lowell Window at First Parish, Brookline, Massachusetts, 2009. Web.

Raguin, Virginia Chieffo, and Mary Clerkin Higgins. "Chapter Nine." Stained Glass: From Its Origins to the Present. New York: H.N. Abrams, 2003. Print.

H. Barbara Weinberg, The Decorative Works of John La Farge (New York, 1977, pp. 360-61. See also Weinberg, "John La Farge's and the Invention of American Opalescent Windows," Stained Glass 67/3 (1972): 4-11.