The

war profoundly impacted the homefront family structure. Wives, children,

and families were left without important members of their families. As

the draft broadened to include first married men, then to fathers, increasingly

families felt the war enter their homes. Husbands and wives feared "his

number being called." And sometimes it was. Eighteen percent of families,

almost one in five, contributed at least one member to the service. By

1945, there were 2,818,000 married men in the Army. Total, over 4 million

servicemen left wives and

The

war profoundly impacted the homefront family structure. Wives, children,

and families were left without important members of their families. As

the draft broadened to include first married men, then to fathers, increasingly

families felt the war enter their homes. Husbands and wives feared "his

number being called." And sometimes it was. Eighteen percent of families,

almost one in five, contributed at least one member to the service. By

1945, there were 2,818,000 married men in the Army. Total, over 4 million

servicemen left wives and  children

behind, without the head of their home, and often without the primary

source of income.(12) Families faced with

this situation in Quinsigamond reflect the different ways families across

the country handled the absence of a father, brother, or husband.

children

behind, without the head of their home, and often without the primary

source of income.(12) Families faced with

this situation in Quinsigamond reflect the different ways families across

the country handled the absence of a father, brother, or husband.

Quinsigamond represents a microcosm for national rationale for American

servicemen. Quinsigamond Village sent its share of men to the War. Men

went for different reasons. Some joined up after Pearl Harbor, others

were drafted away from their families. Attitudes towards service seemed

as varied as each soldier's story and each opinion structured by the individual's

circumstances. Evelyn

Grahn, whose husband was at home for the duration, believed that "most

went willing." However, Martha

Erickson's husband was drafted out of the Reserves, so her idea differs.

Martha explained, "They had to go, that's all. They were drafted."

For the men, their thoughts on enlisting depended on their family status.

Younger men like Vernon

Rudge recalled, "Everybody joined up, most people joined up.

At my age, in my group, they were going in." Edward

Steele, a married father, held a different view. "I didn't want

to go into the war, but I got drafted."

Certainly, plenty of government and societal influence existed to help

these men make their decisions to enlist. Propaganda posters told them,

Uncle Sam needs you! Hollywood, as well, made men feel it was their duty

to go. In the movies, there was always an explanation if an actor was

not in uniform.(13) Norman

Burgoyne felt this pressure to enlist. He "couldn't see being

the only man around." Also, with the implimentation of the Selected

Training and Service Act, men who thought their number was coming up decided

it would be better to enlist and choose their branch. That was what prompted

Marge Dalhquist's brother

to enlist.

Others were not as eager to sign up. Men with wives, with young children,

or those with a duty to younger siblings did not want to abandon their

families. Olaf Rydstrom

worried about his family saying, "The government took care of

them. But, it must have been awful rugged. I worried about that, too."

Wives like Victoria Rydberg feared

their husbands would be called up. And yet, even in the face of fear and

hope of getting passed by, there is a tone of acceptance and of duty.

"All the fellas had to go," recalled Martha

Erickson. And even though families were devastated to see sons and

husbands go, they were proud to say their family served. Families like

the Ingmans hung

stars in the window to share that they had a serviceman in the family.

Florence remembered, "You were all so proud that you had a member

in your family that was serving the country."

But these missing men left great voids in the Quinsigamond community.

They left behind not only vacancies in the factories, but also empty places

at the kitchen table and pay checks that now came from the government.

These fighting fathers and sons created a change in family dynamic, had

profound influences on their children, and had economic impact on their

families.

Mothers now assumed many different roles. To help the "war wife,"

a plethora of advice circulated. So Your Husband's Gone to War!

by Ethel Gorham was "a practical handbook for the wives of the servicemen."

(14) This guide offered advice on everything

from budgeting to loneliness, from wartime diet to letter writing. Women

also received advice from the government in the form of "You're

Monthly Letter from the Army."

Women were told to use pictures, gifts, and activities to teach and remind

their children of their missing fathers. Both Martha

Erickson and Florence Ingman

employed this tactic to make sure their children did not forget their

fathers. This fear was very real for these women. Florence

Ingman's daughter was only five months old when her husband left for

the war. When he returned, she didn't know him.

Children of the war often witnessed their mother's tears. However, most

recall, as one girl from California did, "My mother was the real

hero in our lives." (15) Florence

Ingman recalled finding the strength she needed to keep her family

going. "We were hoping it wouldn't come to this [draft] but…I'm

one that can pick up the pieces."

The women of Quinsigamond had help in their mission to pick up the pieces.

Family and community created the support system these women fell back

on. In American Women in a World of War, Litoff and Smith report

the options for war wives. "With their husbands away in the service,

war wives almost always experienced a reduction in family income. In order

to make ends meet, they moved in with other war wives, took in borders,

returned to their childhood homes to live, and sometimes sought war work."(16)

Quinsigamond women provided examples of each of these trends.

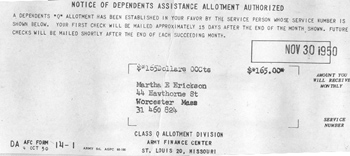

Martha Erickson

relied heavily on her family, for support and for company. "We used

to go up to my mother's and she helped me a lot." Ruth

Burgoyne had established a rotation with other war wives where they

would take turns gathering at each other's homes. Florence

Ingman returned to her childhood home in Vermont. She no longer had

to pay rent and her mother took care of her child so she could work.

These women faced not only loneliness, but also an economic dilema. They

were now living on military dependents pay. Ruth

Burgoyne explained that she would have gotten more if her husband

was an officer. But, since he was a private, she only got $80 a month

and rent was $22.  In

the face of this economic hardship, I was surprised in the interviews

that many Quinsigamond women did not supplement soldiers' pay by

getting a job. Many did not answer the propaganda-enforced call for Rosie

the Riveters in Worcester's factories. Some, like Eleanor

Rudge did, and felt a sense of contribution. Others did not. The simple

reason they gave: children. Martha answered simply, "No, I couldn't

have a job with the little one. I didn't want to leave him alone. And

my mother lived on Burncoat St, so it was kinda far." Ruth

Burgoyne concurred. "None of my friends worked either. We all

had children, remember?" Their reason was reflective of a national

conversation during the war regarding working mothers and latchkey children.

(For more information about working women, click

here.)

In

the face of this economic hardship, I was surprised in the interviews

that many Quinsigamond women did not supplement soldiers' pay by

getting a job. Many did not answer the propaganda-enforced call for Rosie

the Riveters in Worcester's factories. Some, like Eleanor

Rudge did, and felt a sense of contribution. Others did not. The simple

reason they gave: children. Martha answered simply, "No, I couldn't

have a job with the little one. I didn't want to leave him alone. And

my mother lived on Burncoat St, so it was kinda far." Ruth

Burgoyne concurred. "None of my friends worked either. We all

had children, remember?" Their reason was reflective of a national

conversation during the war regarding working mothers and latchkey children.

(For more information about working women, click

here.)

It was not only the war wives and mothers who had to adapt to the missing

servicemen. Absent fathers had a tremendous impact on their children.

Most father-absent research has been done on boys, but clearly the entire

family was impacted. In a book called Children from Five to Ten,

a child's changing perception of the war is explored."Before age

five, the children had little comprehension of the subject, but at five

and six they devised plans for ending the war."(17)

Children also frequently played war games. Victoria

Rydberg's son encapsulated this description of a young homefront boy.

He told his mother, "I'm strong. I can go to war." But, the

limits of his understanding were revealed when he explained to his mother

that, without a doubt, he "would come back."

Many

parents, especially fathers who were leaving, thought their young children

did not understand. Norman Burgoyne

was concerned about his children's perception of the war. He stated, "I

really don't know if they were really old enough to really understand

that there was even a war. All they knew was that their father wasn't

home." Olaf Rydstrom concurred

saying, "They were too little." However, as Olaf

Rydstrom's daughter Bev recalled, memories and pictures of their fathers

at war made lasting impacts. She recalled her father at the train saying,

"You looked sad, we looked sad. Because we knew that he was going

back." Children understood and perceived the danger and fear much

more than their parents thought.

Many

parents, especially fathers who were leaving, thought their young children

did not understand. Norman Burgoyne

was concerned about his children's perception of the war. He stated, "I

really don't know if they were really old enough to really understand

that there was even a war. All they knew was that their father wasn't

home." Olaf Rydstrom concurred

saying, "They were too little." However, as Olaf

Rydstrom's daughter Bev recalled, memories and pictures of their fathers

at war made lasting impacts. She recalled her father at the train saying,

"You looked sad, we looked sad. Because we knew that he was going

back." Children understood and perceived the danger and fear much

more than their parents thought.

Older children also experienced the war in school. Elementary school is

cited as an "impressionable time for children to be exposed to heavy

doses of patriotism and democratic ideology that prevailed on the homefront."

(18) And heavy doses were exactly what

American school children got. By 1948, forty-four states had laws requiring

"instruction on the Constituition" in elementary school. (19)

America had become fiercely patriotic and brought that tone to the schools

and subsequently to the children. As Penny

Copeland remembered, students and teachers would often pray for and

talk about members of the children's families who were abroad fighting.

Quinsigamond Village reflects very national concerns about fathers and

families during war time. First, these men tackled the difficult questions,

Should I enlist? What about my family? How will they manage if I am drafted?

Then, we can examine this community to learn about the various ways life

went on without these men and they impact their absence had. These same

issues were tackled throughout the nation. Quinsigamond Village responded

with a sense of community support for its residents. This kind of response

is what leads many of this generation to look back fondly on what were

truly very difficult times, and why we are told that they are the "greatest

generation."