Over Here, Over There

Introduction | Perception

of the Enemy | News of

the War | Keeping

in Contact | Re-entry

into the Community | Notes | Main

Index

Perception of the Enemy

Although many Americans both at home and abroad could not articulate

clearly what the war was actually about, Americans had no doubt about their

loathing for the enemy. (1) However, this hatred

towards the Japanese and the Germans was expressed differently as a result

of a combination of personal experience and a government sponsored campaign

of racialized propaganda. Individuals both in Quinsigamond Village and in

other parts of the country spoke about fighting Hitler or stopping the atrocities

committed by the Nazis, but Americans believed that the United States was

at war with the Japanese people themselves.

As a result of the United States' experience in World War I,

Americans were disinclined to become involved in the war in Europe and to

recognize the Nazi threat. However, after Italy and Germany declared war on

the United States in 1941, hatred for both Hitler and the Nazi party became

intense. Florence Ingman understood

that Hitler needed to be stopped. "Well the maniac that started it, Hitler.

Yeah, well…I think that everyone felt that they had to get rid of him."

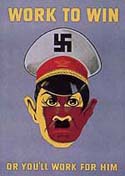

The

government fueled these basic emotions by focusing its public relations campaign

against the evil person of Hitler. Beginning in the late 1930s, "Hitler

the Führer" was well known in the United States, thus, the government

did not have to use much imagination in its propaganda. War ads and posters

feature Hitler prominently and encourage individuals at home to fight against

his government. Nazi soldiers are depicted as machine-like, wicked and cruel.

The

government fueled these basic emotions by focusing its public relations campaign

against the evil person of Hitler. Beginning in the late 1930s, "Hitler

the Führer" was well known in the United States, thus, the government

did not have to use much imagination in its propaganda. War ads and posters

feature Hitler prominently and encourage individuals at home to fight against

his government. Nazi soldiers are depicted as machine-like, wicked and cruel.

However, there is little to no mention of "Germans" or the German

people in the government propaganda. Gordon Forsberg, who lived in the Village

at the time of the war recalls, "You know, it was a case of Hitler being

a, you know…he was just a wacko, and he just had all the people all buffaloed

and stymied." It seems that at least some Americans believed that fundamentally

the German people were not evil, but rather, that a powerful leadership had

overrun them.

The movie industry, which was also censored by the government, also made a

tacit distinction between the two enemies. (2) In

nearly every war movie at least one good German was introduced, as opposed to

the Nazis, while there was rarely a "good Japanese" depicted. However,

as the war dragged on movies and novels began to portray Germans as more barbaric

and heartless than Americans. In his popular 1945 novel Apartment in Athens,

Glenway Wescott wrote that all Germans believed themselves to be supermen and

described even civilian cruelties. (3)

In stark contrast to those veterans whom we interviewed who fought in the Pacific,

veterans who fought in Germany have a fond recollection of the people and the

land. Edward Hult remembers, "I married

a German girl…it was really a shame to see what was going on in Germany,

because it was a beautiful country…it's unbelievable - the beautiful countries,

but that's the way it was." The battles in Europe were fierce and bloody,

but the fight was always against a regime and not a people.

It may have been inevitable that Americans would perceive the enemy of Japan

differently from the German enemy because Japan attacked American soil. Wesley

Holm exemplifies this well, "I didn't have the hatred of the Germans

I did for the Japanese. I positively hated the Japanese 'cause they attacked

us." However, the government exploited existing racism towards Asians and

encouraged it further with anti-Japanese propaganda.

The attack on Pearl Harbor came as a complete and total shock for most Americans,

including every Villager whom we interviewed. "Well, everybody was caught

off guard….It was just, 'wow'. You know, what the? Where'd this come from?"

remembers Forsberg. Tony

Butkus recalls the anger he and many other Americans felt after December

7th: "That was very sneaky, you know, to pull that off. Really got your

blood boiling." Penny Copeland,

a child living in the Village at the time of the war noted, "Well everyone

was like 'my gosh how sneaky!' How sneaky they all were." "Japan's

aggression…stirred the deepest recess of white supremacism and provoked

a response bordering on the apocalyptic." (footnote) Due in part to the

bombing on American soil, many Americans developed a belief that all Japanese

were atrocious, sub-humans.

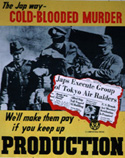

In

the case of Japan, there was no known figure, such as Adolf Hitler, that the

government could depict as the epitome of evil and use to gain support for the

war effort. Emperor Hirohito and General Hideki were not well known before or

during the War. The government focused its efforts on portraying all Japanese

as "sneaky" and suggested that the enemy was all Japanese individuals

(even Japanese-Americans), not just an evil Japanese government. "In depicting

the Axis triumvirate political cartoonists routinely gave the German enemy Hitler's

face and the Italian enemy Mussolini's, but they rendered the Japanese as plain,

homogeneous 'Japanese' creatures: short, round faced, bucktoothed and slant-eyed."

(4) Although Washington officially denied being

involved in a race war, "the War Production Board approved an advertisement

published in 1943 that called for the extermination of all Japanese rats."

(5)

In

the case of Japan, there was no known figure, such as Adolf Hitler, that the

government could depict as the epitome of evil and use to gain support for the

war effort. Emperor Hirohito and General Hideki were not well known before or

during the War. The government focused its efforts on portraying all Japanese

as "sneaky" and suggested that the enemy was all Japanese individuals

(even Japanese-Americans), not just an evil Japanese government. "In depicting

the Axis triumvirate political cartoonists routinely gave the German enemy Hitler's

face and the Italian enemy Mussolini's, but they rendered the Japanese as plain,

homogeneous 'Japanese' creatures: short, round faced, bucktoothed and slant-eyed."

(4) Although Washington officially denied being

involved in a race war, "the War Production Board approved an advertisement

published in 1943 that called for the extermination of all Japanese rats."

(5)

The American government also released numerous accounts of extreme brutality

by the Japanese, not necessarily Japanese soldiers, in combat. Reports of the

suicide bombings by Kamikaze pilots furthered this maniacal, sub-human stereotype.

Although these reports may have been accurate, by failing to make a distinction

between the army of Japan and the citizenry of Japan both in military reports

and in the media in general, the public was continuously fed racist images and

messages.

However, there were some individuals who were able to see through the racialization

of the war and did not believe that all Japanese, particularly Japanese Americans,

were to blame for the War. "But I thought it was so terrible that just

because they were Japanese how they had to suffer for the mistake of someone

else who was Japanese. It covered over to everybody because they were Japanese,

they all had to suffer," believed Grace

Butkus about the forced internment of Japanese-Americans.

No veteran who fought in the Pacific theater with whom we spoke had any positive

memories of the people, as was the case with Germany. Veterans themselves speak

in terms of the Japanese population and not in terms of the Japanese army. "See

we were fighting against the Japs, they were very sneaky," remembers Ed

Steele. Holm says, "I ended up in Japan…and I don't know how many

people got killed because of those Japs. And they were mean. They were a mean

people."

It is apparent, even in our small sample of the Village residents that the

government was successful in magnifying the preexisting anti-Asian prejudices

within the United States and transforming them into true hatred. Shortly after

the bombing of Pearl Harbor Allan Nevins, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winning

historian, observed, "probably in all our history, no foe has ever been

so detested as were the Japanese." (6) This

discrimination fueled support for the war both at home and abroad.

The

government fueled these basic emotions by focusing its public relations campaign

against the evil person of Hitler. Beginning in the late 1930s, "Hitler

the Führer" was well known in the United States, thus, the government

did not have to use much imagination in its propaganda. War ads and posters

feature Hitler prominently and encourage individuals at home to fight against

his government. Nazi soldiers are depicted as machine-like, wicked and cruel.

The

government fueled these basic emotions by focusing its public relations campaign

against the evil person of Hitler. Beginning in the late 1930s, "Hitler

the Führer" was well known in the United States, thus, the government

did not have to use much imagination in its propaganda. War ads and posters

feature Hitler prominently and encourage individuals at home to fight against

his government. Nazi soldiers are depicted as machine-like, wicked and cruel.

In

the case of Japan, there was no known figure, such as Adolf Hitler, that the

government could depict as the epitome of evil and use to gain support for the

war effort. Emperor Hirohito and General Hideki were not well known before or

during the War. The government focused its efforts on portraying all Japanese

as "sneaky" and suggested that the enemy was all Japanese individuals

(even Japanese-Americans), not just an evil Japanese government. "In depicting

the Axis triumvirate political cartoonists routinely gave the German enemy Hitler's

face and the Italian enemy Mussolini's, but they rendered the Japanese as plain,

homogeneous 'Japanese' creatures: short, round faced, bucktoothed and slant-eyed."

In

the case of Japan, there was no known figure, such as Adolf Hitler, that the

government could depict as the epitome of evil and use to gain support for the

war effort. Emperor Hirohito and General Hideki were not well known before or

during the War. The government focused its efforts on portraying all Japanese

as "sneaky" and suggested that the enemy was all Japanese individuals

(even Japanese-Americans), not just an evil Japanese government. "In depicting

the Axis triumvirate political cartoonists routinely gave the German enemy Hitler's

face and the Italian enemy Mussolini's, but they rendered the Japanese as plain,

homogeneous 'Japanese' creatures: short, round faced, bucktoothed and slant-eyed."