From Bust to Boom: Leaving the Depression Behind

“[My parents] talked about the Depression a lot. I came along

a few years later, but they were still talking about it, and a lot of

them changed their ways of life after that because they never wanted

to be left without money again.”

—Penny

Copeland

At the onset of World War II, communities like Quinsigamond

Village still rested on shaky economic ground. While President Roosevelt’s

New Deal policies had set economic recovery in motion, by the late 1930s

the nation had yet to rebound from the financial despair wrought by

the Great Depression. As high levels of unemployment and underemployment

persisted amidst an industrial sector that “…was but a shadow

of its past might,” many wondered whether the coming war would

return America to the prosperity it once enjoyed.(1)

Evelyn Grahn

recalls the uneasy memories that the Depression burned into the minds

of those who lived through it:

“I

remember when the market crashed in twenty-nine…anytime I see a

bank ad nowadays, I can see that…there were a lot of little banks

in Millbury, and there were long lines of people outside. And the doors

were closed. And Mr. Sundquist explained to me that the banks had closed

the doors and people couldn’t get their money and that’s why

people were standing out there…I saw then how much that meant to

people.” “I

remember when the market crashed in twenty-nine…anytime I see a

bank ad nowadays, I can see that…there were a lot of little banks

in Millbury, and there were long lines of people outside. And the doors

were closed. And Mr. Sundquist explained to me that the banks had closed

the doors and people couldn’t get their money and that’s why

people were standing out there…I saw then how much that meant to

people.”

These recollections of unyielding bank lines and parents still fretting

over family finances undoubtedly influenced a generation of villagers

awaiting the advent of wartime prosperity. In his account of the American

home front during World War II, V Was For Victory, John Morton

Blum speaks of this economically anxious pre-war generation:

“In December 1941 young American men and women had known nothing

but depression. Those of draft age, twenty years old, born in 1921,

had been only eight when the market collapsed, had looked for jobs they

could not find since 1936 or 1937, or had attended school and college,

working at odd jobs while they studied, with little expectation of any

other kind of work…[T]he young were anxious about postwar depression.

[Their parents], who were enjoying prosperity during the war for the

first time in more than a decade, savored it the more for fear that

it would vanish.”(2)

Memories over the lingering effects of the Great Depression, then,

created a sense of frugal prosperity that characterized life in Quinsigamond

during World War II. In this village, the wartime boom may have provided

an extra financial boost to working families, but in no way did it launch

a consumer frenzy where goods were plentiful and spending was carefree.

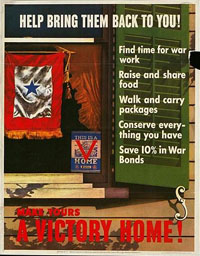

Instead, the strict rationing and long work hours endured by Quinsigamond

residents effectively conserved spending to a comfortably subsistent

level. Says Tony

Butkus, “We were getting by, just getting by. Just enough to

pay your bills and make a living.” His wife, Grace

Butkus, agrees that life after war brought greater economic security:

“No, I remember we were worse off [during the war] because I

distinctly remember it was like being on strike, because we didn’t

have full and plenty. You know, we didn’t have an abundance,

like you would if you were well off.”

The villagers could not enjoy the “full and plenty” that

Grace speaks of due to the rationing program initiated by the federal

government. Of all the memories expressed by the residents of Quinsigamond

concerning World War II, rationing stands out as a nuisance mentioned

frequently by nearly every single interviewee. (See

rationing.) Because of this, and because of the sacrifice rationing

necessarily entailed, it is likely that the economic prosperity which

wartime production brought to Quinsigamond is not remembered as distinctly.

Sonja

Gullbrand remembers that during the war “…there was more

production, but then of course after the war it was much better.”

Similarly, the increased hours that kept people on the job late into

the evening and through the weekends stood out more in workers’

minds than did a little extra cash in their pockets.

Still, the boom in employment and competitive wages brought

about by the wartime production carried on by American Steel and Wire

and a few other industries undoubtedly provided the economy with the

stimulus necessary to awaken it from its Depression-era slumber. Blum

tells us that

By 1943, the unemployment rate stood at 1.3 percent, less than one-tenth

of the figure in 1937, the best year during the Great Depression.

Between 1935 and 1945, the number of jobless people dropped from 9

million to 1 million, with jobs available to virtually anyone who

wanted work. (3)

There was little want for employment in Quinsigamond Village,

as thousands were employed by American Steel and Wire while others found

jobs in the dozens of markets that dotted the village streets. Fortunately,

the decent wages and high levels of employment brought about by wartime

production were able to sustain themselves during the transition into

a peacetime economy.

It took the completion of this transition, however, to provide a sense

of economic security to the residents of Quinsigamond Village which

finally allowed them to enjoy the prosperity that had already started

in the early 40s. Edward

Hult recalls that “…after the war, of course, when industry

started moving, and there was a lot of jobs around, people had money

in their pocket. And that's one thing that helped them come along.”

While industry was certainly moving during the war, it moved in a direction

dictated by a government that needed as many guns, tanks, and ships

possible to win. After the war ended, however, industry was free to

pursue production decisions that would meet increasing consumer demands

for automobiles, refrigerators, washing machines, and other such wartime

luxuries.(4) Mr.

Hult comments on this shift: “[Take] the automotive industry--I

mean, during the war, you couldn't even get a tire for your car and

then they finally started producing cars.”

For

a working-class village such as Quinsigamond, the economic progress

of the war years brought welcome relief from the Depression-era memories

of closed banks and jobless families. George

White recalls that “The war brought [people] out of the Depression,

and they started to enjoy a prosperity that they hadn’t seen for

years.” Still, the memories of the Depression, along with the tireless

work efforts of the community and the sacrifices rationing demanded,

prevented a wartime recovery characterized by the carefree spending

on luxuries that frequently caricatures this period. Instead, families

were able to make a decent living while awaiting the postwar era that

would provide them with a sense of security and prosperity that had

been lost during recent challenging times. For

a working-class village such as Quinsigamond, the economic progress

of the war years brought welcome relief from the Depression-era memories

of closed banks and jobless families. George

White recalls that “The war brought [people] out of the Depression,

and they started to enjoy a prosperity that they hadn’t seen for

years.” Still, the memories of the Depression, along with the tireless

work efforts of the community and the sacrifices rationing demanded,

prevented a wartime recovery characterized by the carefree spending

on luxuries that frequently caricatures this period. Instead, families

were able to make a decent living while awaiting the postwar era that

would provide them with a sense of security and prosperity that had

been lost during recent challenging times.

|