The Arsenal of Democracy

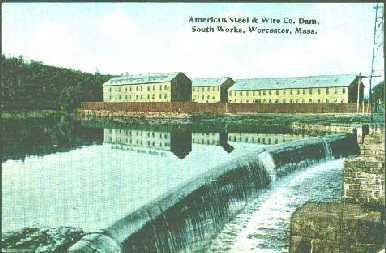

"Everybody put their shoulder to the wheel and they worked at it and they worked hard. Whether you were at American Steel and Wire or Norton Company, whatever company you then worked for, you helped them. Worcester's a great town."-Edward Hult

The

mobilization of the American home front during World War II required a massive

cooperative effort between the federal government, the business community,

and the nation's workforce. Organizing industry around intense wartime production

goals, and ensuring a compliant labor force that would work around the clock

proved to be tasks best undertaken by the Roosevelt administration's vast

federal bureaucracy. The results of these efforts could be seen in communities

like Quinsigamond, where the existence of the American Steel and Wire plant

became a central presence in the lives of the villagers. With a workforce

of 7,000 people from both Quinsigamond Village and surrounding areas, American

Steel and Wire provided for the economic security of the village while demanding

a constant and tireless effort from its employees. (5)

The

mobilization of the American home front during World War II required a massive

cooperative effort between the federal government, the business community,

and the nation's workforce. Organizing industry around intense wartime production

goals, and ensuring a compliant labor force that would work around the clock

proved to be tasks best undertaken by the Roosevelt administration's vast

federal bureaucracy. The results of these efforts could be seen in communities

like Quinsigamond, where the existence of the American Steel and Wire plant

became a central presence in the lives of the villagers. With a workforce

of 7,000 people from both Quinsigamond Village and surrounding areas, American

Steel and Wire provided for the economic security of the village while demanding

a constant and tireless effort from its employees. (5)

Before President Roosevelt could get wartime communities like Quinsigamond

booming, however, he needed to stimulate the national economy. Through unprecedented

amounts of federal defense spending suggested by the economist John Maynard

Keynes, an increased emphasis on the demand for military production over that

of civilian needs, and the practice of underwriting the costs of business

expansion, Roosevelt moved the economy toward full recovery while completing

the process of wartime industrial mobilization.

Allan Winkler claims that "Mobilization in all areas succeeded because

government was willing to spend whatever was necessary to win the war."

(6) Thus, in 1939, federal outlays totaled $8.9

billion and by 1945 they were $98.4 billion. Once this massive federal spending

helped initiate economic recovery, Roosevelt needed to deal with the problem

of convincing industry to make a shift from civilian to military production.

As the example of the auotmobile industry demonstrates, this was no easy task:

[The auto industry's] assembly lines were needed to make planes and tanks, and it was asked to produce one-fifth of all war material in the United States. But car manufacturers were in no hurry. With the country recovering from the depression, their top priority was the huge civilian market coupled with Americans' renewed purchasing power, which translated into large profits. (7)

To combat these difficulties, Roosevelt created the Office of

Production and Management, which narrowed the scope of what industry could

produce to necessary wartime goods. For the auto industry, that meant that

Ford traded cars for B-24 bombers and Chrysler did the same for tanks.(8)

Says Hector Letourneau,

"They got the stuff out that they needed. In fact, instead of building

auotmobiles, they turned around and built tanks, built jeeps. They didn't

build no automobiles from 1942 to 1946 because everything was for the war."

To sweeten the deal for big business, the federal government agreed to initiate

policies that underwrote the expansion of plant production, protected companies

against antitrust legislation, offered tax breaks, and implemented a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee

system in which the government guaranteed all development and production costs.

(9)

In

this way, Roosevelt and his administration, in cooperation with the captains

of industry, effectively mobilized communities across the country for wartime

production. In Worcester, the War Production Board estimated that "Of

53,000 manufacturing workers…40,000 were engaged in production for the

country's defense." (10) And of course, 7,000

of those workers were working for American Steel and Wire in Quinsigamond

Village. During the war, American Steel and Wire produced "…cables

that used synthetic materials rather than scarce rubber. The company also

developed a high-strength listening device towing cable that the Navy used

for locating German U-boats." (11) Other

companies employing residents of the Village included Norton Company, Reed-Prentice

Corporation, and Wyman-Gordon. In 1941, Norton Company already employed nearly

6,000 men and women, 2,140 of which were working solely on defense production,

creating machine tools such as crankshafts, pistons, and rotating parts all

"vital to the making of airplanes, tanks, guns, motor vehicles and the

mechanical equipment of defense." (12)

Meanwhile, Reed-Prentice was in the machine tool industry, creating the tools

that manufacturers needed to modernize industry in order to create an effective

industrial defensive program. Reed-Prentice specialized "…in the

manufacture of engine and tool room lathes, vertical milling and die sinking

machines, jog borers, and die-casting machines." (13)

In

this way, Roosevelt and his administration, in cooperation with the captains

of industry, effectively mobilized communities across the country for wartime

production. In Worcester, the War Production Board estimated that "Of

53,000 manufacturing workers…40,000 were engaged in production for the

country's defense." (10) And of course, 7,000

of those workers were working for American Steel and Wire in Quinsigamond

Village. During the war, American Steel and Wire produced "…cables

that used synthetic materials rather than scarce rubber. The company also

developed a high-strength listening device towing cable that the Navy used

for locating German U-boats." (11) Other

companies employing residents of the Village included Norton Company, Reed-Prentice

Corporation, and Wyman-Gordon. In 1941, Norton Company already employed nearly

6,000 men and women, 2,140 of which were working solely on defense production,

creating machine tools such as crankshafts, pistons, and rotating parts all

"vital to the making of airplanes, tanks, guns, motor vehicles and the

mechanical equipment of defense." (12)

Meanwhile, Reed-Prentice was in the machine tool industry, creating the tools

that manufacturers needed to modernize industry in order to create an effective

industrial defensive program. Reed-Prentice specialized "…in the

manufacture of engine and tool room lathes, vertical milling and die sinking

machines, jog borers, and die-casting machines." (13)

As noted earlier, the federal government demanded that companies such as American

Steel and Wire turn out military goods quickly and in high quantities. Accordingly,

the demand on workers became unyielding as the war progressed. Nationally,

"The average workweek expanded from 40.6 hours to 45.2 hours between

1941 and 1942; in some factories the norm became a 50- or 60-hour workweek.

And virtually all workers put in some overtime for which they were paid time-and-a-half."

(14) The situation was no different in Worcester,

where "Working in three shifts around the clock was not unusual as companies

tried feverishly to meet demand." (15)

And perhaps the best example of this intensity was provided by American Steel

and Wire itself: "Managers there put in 14- to 16-hour days and steelworkers

a minimum of 10-hour days…[it] operated every minute of the war except

from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Christmas days…" (16)

Indeed, many of the Quinsigamond residents who worked at the mill remember

the grueling schedule:

"One of the things I remember distinctly…is that one of the jobs that you had…you stayed 'til two o'clock in the morning or like four or five o'clock and work straight through. And after the war was over, the young fellas would walk off the job at eleven o'clock at night, they didn't do that anymore. I remember distinctly how devoted and how hard you guys worked to get production and to get the things out. It was a big project." (Grace Butkus)

"…They didn't even have a cafeteria that I knew of. My husband took his lunch. But he worked all three shifts. Seven to three, three to eleven, and eleven to seven. And, we had three children…I don't know how I got through it, but I did." (Victoria Rydberg)

"…We worked forty hours a week and then of course when the war got going, we put in more hours. And the worst of it was…we couldn't even work in the plant on Sundays, so we went down to the bosses' house down in Oxford, and did our work down there, and then we didn't get paid for it…" (Edward Hult)

In fact, the production schedule became so extreme, and so rushed, that stressed-out managers would be called in the middle of the night to oversee some big production job that needed finishing. Remembers Tony Butkus,

"I didn't know this until after the war, but during the war they used to call [my father] with problems. He was a foremen of a department, of a big department. And they used to call him maybe three, four times a night. Finally it got to him. My mother thought he was going to have a breakdown or something, and they'd call him about all these problems they were having during the night. During the daytime he was there so he worked, but so, she went down there and talked to his boss and told him…He needed more help!"

Long hours and stressed conditions amidst a factory dealing

with dangerous machinery was bound to result in accidents, and Penny

Copeland recalls that there were too many: "[My father] had a brother

who got killed by the hot rods…there were a lot of accidents down there."

Still, despite these trying conditions, the former employees of American Steel

and Wire recall a sense of duty and patriotism that drove them to their work.

Winkler contends that "Though they complained about the growing differential

between their wage rates and business profits, workers plunged in and did

what was necessary to produce the implements of war." (17)

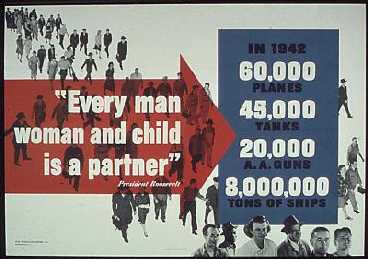

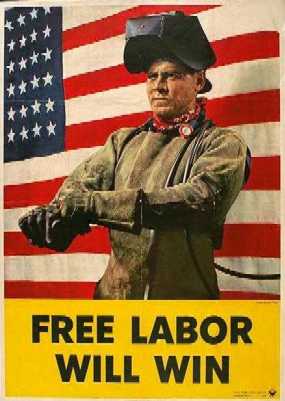

During the war, the Office of War Information produced thousands of posters

and pamphlets with the purpose of rallying Americans to the cause. Much of

this propaganda was directed toward the labor force, reminding the men and

women in the factories at home that their work would contribute to victory.

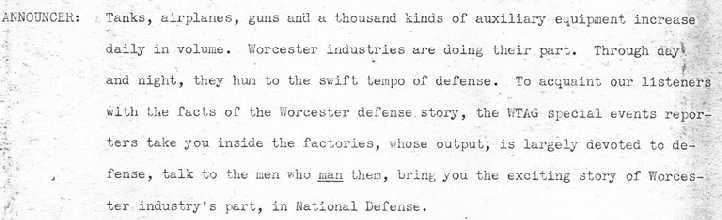

In Worcester specifically, other tactics included the "Defense

on Parade" radio show, which highlighted the devotion of local companies

to defense production.

It was within this atmosphere that the men and women of American Steel and Wire marched to the factory every single day:

"[Working] was my contribution…when they didn't take [my husband] on account of his heart murmur, I figured well, this family has to do something for the war-and so I would apply for a job." (Grace Butkus)

"You had to be dedicated, because that was your part for the service…[Working] was your contribution, and it's the way you made a living." (Tony Butkus)

Judging from the comments of Quinsigamond residents, as well

as the economic figures from the time period, it seems that making a decent

living at American Steel and Wire was not a problem. George

White says that "[American Steel and Wire's] wages were tops. Oh

yeah, in this city for industry…they're wages were excellent." Of

course, excellent for the times still meant, as Tony

Butkus says "just getting by," and Penny

Copeland adds that "…believe me, we were never rich." Still,

in contrast to the Depression years, the wartime boom provided a welcome financial

relief (See Depression).

Factory life at American Steel and Wire also fostered a strong sense of community

among those who worked there. Many of the complaints from the villagers concerning

long hours and tough work conditions were often softened with recollections

of friendships made and relationships strengthened through life at the mill:

"Long hours, but everybody was wonderful. They were wonderful."

(Eleanor Rudge) Tony

Butkus elaborates on this point, and joins many other interviewees in

mentioning how workers would get to the mill early simply to enjoy time with

friends and neighbors:

"…We had all different nationalities, different religions, and we all got along together. And as a matter of fact, we'd all congregate down at what they called a Guards Shanty before we'd get into work, and we'd…shoot the breeze talking amongst ourselves this and that. You'd spend maybe an hour just talking before you'd have to be in…"

The mill's involvement with the community did not stop at the

factory door, however. It built a movie theatre down the street, formed a

baseball team which played in the industrial league, and owned a park complete

with a neighborhood pool. Eleanor

Rudge attributes this community involvement to the need to keep overworked

employees content: "They had to keep their workers happy, because they

were losing them too."

Indeed, an unhappy workforce laboring long hours would endanger the high level of productivity the mill was achieving. At American Steel and Wire, however, labor unrest was minimal. When the company unionized, many residents welcomed the change. Tony Butkus claims that he worked at American Steel and Wire for so many years "…because we had the Union at that time." Similarly, Victoria Rydberg remembers that when the Union came to town, her husband "…got very good summer money and vacation money that he had never gotten before. That was a good thing." Not all residents agree, however. Edward Hult, whose father served as Superintendent of American Steel and Wire, fails to see the benefits that the union brought:

"I guess it was after the war [American Steel and Wire] signed with a union…the people, I could remember some of them, they signed for it and they weren't sure. All the sudden they realized they had to pay five dollars a month. What were they going to get for their five dollars? Not much."

On the national level, World War II was a period of time in which labor leaders saw a vast increase in union membership and were able to obtain better wages for their members. Still, the cooperation between business, labor, and the government that the war effort required hurt the cause of the more radical elements within the labor movement. Winkler argues that

"Most historians studying labor trends have acknowledged that industrial union activity came of age during the war. Labor and management, committed to a common goal, learned to talk together and, under government direction, bargain collectively. The whole process enhanced industrial stability and provided workers with more job security than they had ever known." (18)

Thus, even though the divisions between the AFL and CIO remained deep, wage battles between the government and labor raged on, and the strife between labor and management caused an increase in labor activity, the intensity of labor's struggle was far more subdued during World War II then it had been before war. In fact, "As the War Labor Board and organized labor clashed over wages, other parts of American life seemed totally unaffected by the defense uproar." (19) In many communities, Quinsigamond included, both management decisions to work labor long hours and labor decisions to organize were met with little resistance by either party involved.

Labor's complacency and American Steel and Wire's paternalistic approach to employment, then, resulted from a close-knit Quinsigamond community that was surrounded by calls to sacrifice for a greater cause. People worked long, stressful hours for average pay, but they had each other to complain to over a donut at the bakery or in the early morning before work started. With the government reminding the American citizenry that it was "free labor" that would win the war, those who saw friends and family members serve the nation abroad felt compelled to serve it at home as well.